Sensemaking and Human-Centred Design: a Practice Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Operating Together: 12 Years of Collaboration Between RCSI and COSECSA

Operating Together: 12 Years of Collaboration Between RCSI and COSECSA Leading the world to better health 1 Leading the world to better health Dr Enock Ludzu and patient, Mangochi District Hospital, Malawi. Photo courtesy of Antonio Osuna and SURG-Africa. Edited by Eric O’Flynn, Krikor Erzingatsian, Declan Magee and the RCSI/COSECSA Collaboration Dedication To everyone who made this happen. 1 Authors’ Note The story of the collaboration between the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland (RCSI) and the College of Surgeons of East, Central and Southern Africa (COSECSA) can only be properly told in conjunction with an account of the story of COSECSA. This book cannot, and does not attempt to, give a comprehensive history of COSECSA, only that part of it necessary for a better understanding of the story of the RCSI/ COSECSA Collaboration Programme. Recounting the exciting and inspiring story of COSECSA itself is for another day. We look forward to reading such an account in the years to come! 2 Foreword 4 Chapter 1 The Global Surgical Care Crisis 6 Chapter 2 A Vision for a Surgical Training College 10 Chapter 3 The Genesis of the Collaboration Programme 14 Chapter 4 The COSECSA Experience 23 Chapter 5 Examinations and Training Support 28 Chapter 6 Training Support 34 Chapter 7 Rural Surgery 49 Chapter 8 Harnessing the Power of Data 52 Chapter 9 Building the Organisation 56 Chapter 10 The Voice of COSECSA 63 Chapter 11 Evolution of the Collaboration – Successes, Failures and Lessons Learned 67 Chapter 12 Looking Forward – A Lot Done, More To Do 72 Chapter 13 In Memoriam 76 Bibliography 78 Acknowledgements 82 Glossary 83 3 Foreword by Minister of State for the Diaspora and International Development, Ciarán Cannon TD The late Kofi Annan, former United Nations Secretary-General and a great friend of Ireland, said that “The biggest enemy of health in the developing world is poverty”. -

CBRNE-Terrorism Newsletter December 2014

CBRNE-Terrorism Newsletter December 2014 1 www.cbrne-terrorism-newsletter.com CBRNE-Terrorism Newsletter December 2014 2 www.cbrne-terrorism-newsletter.com CBRNE-Terrorism Newsletter December 2014 3 www.cbrne-terrorism-newsletter.com CBRNE-Terrorism Newsletter December 2014 CBRNE-Terrorism Newsletter – 2014© December 2014 Website: www.cbrne-terrorism-newsletter.com 10 YEARS: 2005-2014 Editor-in-Chief BG (ret) Ioannis Galatas MD, MA, MC PhD cand Consultant in Allergy & Clinical Immunology Medical/Hospital CBRNE Planner Senior Asymmetric Threats Analyst CBRN Scientific Coordinator @ RIEAS Athens, Greece Contact e-mail: [email protected] Assistant Editor Panagiotis Stavrakakis MEng, PhD, MBA, MSc Hellenic Navy Capt (ret) Athens, Greece Co-Editors/Text Supervisors 1. Steve Photiou, MD, MSc (Italy) 2. Dr. Sarafis Pavlos, Captain RN(ret‘d), PhD, MSc (Greece) 3. Kiourktsoglou George, BSc, Dipl, MSc, MBA, PhD (cand) (UK) 4 Advertise with us! (New price list) CBRNE-Terrorism Newsletter is published on-line monthly and distributed free of charge. Starting from 2014 issue all advertisements will be charged as following: Full page (A4) 100€ Double pages (A4X2) 200€ EDITOR Mendor Editions S.A. 3 Selinountos Street 14231 Nea Ionia Athens, Greece Tel: +30 210 2723094/-5 Fax: +30 210 2723698 Contact e-mail: Valia Kalantzi [email protected] Cover: Nicotiana benthamiana, the plant from which ZMapp is derived. DISCLAIMER: The CBRNE-Terrorism Newsletter® is a free online publication for the fellow civilian/military First Responders worldwide. The Newsletter is a collection of papers related to the stated thematology, relevant sources are provided and all info provided herein is from open Internet sources. Opinions and comments from the Editorial group or the authors publishing in the Newsletter do not necessarily represent those of the Publisher. -

Ebola and MSF

Ebola and MSF Introduction for schools December 2014 Ebola epidemics “MSF has been working in ‘Ebola settings’ for almost 20 years, so we have an enormous amount of knowledge on safe behaviour, infection control and patient management.” - Kimberly Larkins, MSF Who are Medecins Sans Frontieres/ Doctors Without Borders (MSF)? • We are an independent international medical humanitarian aid organisation • Founded in 1971, we provide emergency medical care to those people who need it the most in over 70 countries around the world • In 1999 MSF won the Nobel Peace Prize Medical Emergencies War and Civil Conflict Refugee and IDP Crises Nutritional Crises Epidemics such as Ebola Natural Disasters History Ebola was first identified in 1976 in remote villages near tropical rainforests in Sudan and Democratic Republic of Congo, Central Africa. Can you find them on the map? Map: http://victoriastaffordapsychicinvestigation.files.wordpress.com/2012/07/map-of-africa-countries-nambia-angola-south-africa-madagascar-island-se-mozambique- tanzania-kenya-somalia-ethiopia-sudan-egypt-libya-algeria.gif?w=600 What is Ebola? • One of the world’s most deadly diseases, but you do not necessarily die if you catch it. • Ebola has not been spread in the UK, so you needn’t worry! • Ebola is transmitted through close contact with bodily fluids such as blood, sweat and saliva. Ebola is far more difficult to catch than measles that is transmitted through the air. • Patients with Ebola need to be treated in isolation by staff wearing protective clothing. Symptoms "The feeling was overpowering. Ebola is like a sickness from a different planet. It comes with so much pain." - SALOME KARWAH, EBOLA SURVIVOR • People are not infectious (cannot pass on the virus) until they show symptoms. -

Global Health Initiatives Building a Healthier World

Global Health Initiatives Building a healthier world UN Sustainable Development Goal 3 Good Health and Wellbeing Global Health Initiatives Building a healthier world Special global health article collection celebrating the 40th anniversary of the Declaration of Alma-Ata FOREWORD 1 Achieving universal health coverage in an era of emerging global health threats Kieran Walsh, Lalitha Bhagavatheeswaran, Mitali Wroczynski, Elisa Roma RESEARCH REPORT 2 Socioeconomic inequalities in child vaccination in low/middle-income countries: what accounts for the differences? From Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health Mohammad Hajizadeh RESEARCH 9 Risk factors and risk factor cascades for communicable disease outbreaks in complex humanitarian emergencies: a qualitative systematic review From BMJ Global Health Charlotte Christiane Hammer, Julii Brainard, Paul R Hunter 19 Evaluation of a programme for ‘Rapid Assessment of Febrile Travelers’ (RAFT): a clinic-based quality improvement initiative From BMJ Open Farah Jazuli, Terence Lynd, Jordan Mah, Michael Klowak, Dale Jechel, Stefanie Klowak, Howard Ovens, Sam Sabbah, Andrea K Boggild SHORT RESEARCH REPORT 26 Prevalence and factors associated with the use of antibiotics in non-bloody diarrhoea in children under 5 years of age in sub-Saharan Africa From Archives of Disease in Childhood Asa Auta, Brian O Ogbonna, Emmanuel O Adewuyi, Davies Adeloye, Barry Strickland-Hodge SHORT REPORT 30 Infectious disease outbreaks: how online clinical decision support could help From BMJ Simulation & Technology Enhanced -

Upgraded Kharaitiyat Junction to Ease Traffic

BUSINESS | Page 1 SPORT | Page 1 Peshawar Zalmi crowned INDEX DOW JONES QE NYMEX QATAR 2-9, 28 COMMENT 26, 27 Barwa eyes investment REGION 10 BUSINESS 1-7, 14-16 PSL 20,981.00 10,721.15 53.33 ARAB WORLD 10, 12 CLASSIFIED 8-13 opportunities to ensure -25.00 -30.95 +0.72 INTERNATIONAL 13-25 SPORTS 1-8 champions -0.12% -0.29% +1.37% profi table revenue growth Latest Figures published in QATAR since 1978 MONDAY Vol. XXXVIII No. 10384 March 6, 2017 Jumada II 7, 1438 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals Emir meets Bahrain’s Crown Prince Upgraded In brief ARAB WORLD | Labour Kharaitiyat Qatar takes part in ALO Council talks Qatar is participating in the 86th session of the Arab Labour Organisation (ALO) Council which junction to started in Cairo yesterday. HE the Minister of Administrative Development, Labour and Social Aff airs Dr Essa Saad al-Jafali al-Nuaimi headed Qatar’s delegation to the meeting. The meeting, besides following up ease traffi c on the progress of the 85th session which was held in Doha in October, Major boost for traff ic as Al 11,000 vehicles per hour, which alone HH the Emir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani met at the Emiri Diwan yesterday with Prince Salman bin Hamad al-Khalifah, will look into the preparations for the Kharaitiyat Interchange opens are coming from Al Rufaa Street. the Crown Prince, Deputy Supreme Commander and First Deputy Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Bahrain. Talks during the annual meeting of the Arab Group “Al Kharaitiyat Interchange is so criti- meeting dealt with the deep fraternal relations of co-operation between the two countries and means of enhancing them in all participating in the 106th Session of cal that it connects with all areas around fields to better serve the common interest of the two countries. -

Versão Corrigida

Versão Corrigida Universidade de São Paulo Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas Departamento de Antropologia Social O cuidado perigoso: tramas de afeto e risco na Serra Leoa (A epidemia do ebola contada pelas mulheres, vivas e mortas) Denise Pimenta (Versão Corrigida) Tese apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Antropologia Social do Departamento de Antropologia Social da Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo, para a obtenção do título de doutora em Antropologia Social. Orientador: Prof. Dr. John Cowart Dawsey São Paulo, 2019 O cuidado perigoso: tramas de afeto e risco na Serra Leoa (A epidemia do ebola contada pelas mulheres, vivas e mortas) (Versão Corrigida) Autorizo a reprodução e divulgação total ou parcial deste trabalho, por qualquer meio convencional ou eletrônico, para fins de estudo e pesquisa, desde que citada a fonte. Catalogação na Publicação Serviço de Biblioteca e Documentação Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo Pimenta, Denise P644c O cuidado perigoso: tramas de afeto e risco na Serra Leoa (A epidemia do ebola contada por mulheres, vivas e mortas) / Denise Pimenta ; orientador John Cowart Dawsey. - São Paulo, 2019. 351 f. Tese (Doutorado)- Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo. Departamento de Antropologia. Área de concentração: Antropologia Social. 1. Serra Leoa (África do Oeste). 2. Guerra Civil. 3. Epidemia do ebola (2013-2016). 4. Mulheres. 5. "Cuidado Perigoso". I. Cowart Dawsey, John, orient. II. Título. UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO FACULDADE DE F FACULDADE DE FILOSOFIA, LETRAS E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS ENTREGA DO EXEMPLAR CORRIGIDO DA DISSERTAÇÃO/TESE Termo de Ciência e Concordância do (a) orientador (a) Nom e do (a) aluno (a) : Denise Moraes Pim enta Data da defesa: 15/ 03/ 2019 Nom e do Prof. -

Qatar's Private Education Sector Revenue Jumps

BUSINESS | Page 1 SPORT | Page 8 Twofold increase in England’s Portuguese Jones is fi rms INDEX champion DOW JONES QE NYMEX QATAR 6-14, 34 COMMENT 32, 33 exporting REGION 15 BUSINESS 1 -7, 21-24 to Qatar again 20,863.00 10,361.03 48.78 ARAB WORLD 15, 16 CLASSIFIED 8-20 -19.00 +69.17 +0.03 INTERNATIONAL 17-31 SPORTS 1 - 8 -0.09% +0.67% +0.06% Latest Figures published in QATAR since 1978 SUNDAY Vol. XXXVIII No. 10397 March 19, 2017 Jumada II 20, 1438 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals Abbas arrives in Doha Qatar’s private In brief EUROPE | Security education sector Attacker shot dead at Paris’ Orly airport Troops at Paris’ Orly airport yesterday shot dead a man who tried to grab a female soldier’s weapon, revenue jumps triggering a major security alert that shut down the airport, leaving atar’s private education sector The ministry has projected demand for tween 2010 and 2015, which highlights thousands stranded. Prosecutors has seen nearly threefold rise school education to continue to grow the increasing role of the private sector said they had opened an anti-terror Qits revenue in four years - to over the next fi ve years. in the education sector. investigation. France goes to the QR5.8bn in 2015 from QR2bn in 2011, The report shows an 83.7% increase The report highlighted the “impor- polls on April 23 in the first round shows a study by the Ministry of Econ- in the number of university students tant” contribution of the sector to eco- of a two-stage presidential election omy and Commerce (MEC). -

Organizing for Resilience: Mobilization by Sierra Leonean Diaspora Communities in Response to the 2014-2015 Ebola Crisis

Organizing for Resilience: Mobilization by Sierra Leonean Diaspora Communities in Response to the 2014-2015 Ebola Crisis The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Manning, Ryann. 2017. Organizing for Resilience: Mobilization by Sierra Leonean Diaspora Communities in Response to the 2014-2015 Ebola Crisis. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42061468 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Organizing for Resilience: Mobilization by Sierra Leonean Diaspora Communities in Response to the 2014-2015 Ebola Crisis A dissertation presented by Ryann Manning to The Committee for the Ph.D. in Business Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Organizational Behavior Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2017 © 2017 Ryann Manning All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisors: Author: Professor Michele Lamont (co-chair) Ryann Manning Kathleen McGinn (co-chair) Organizing for Resilience: Mobilization by Sierra Leonean Diaspora Communities in Response to the 2014-2015 Ebola Crisis ABSTRACT The question of how social groups prepare for and respond to disasters has long been of interest to sociologists and organizational scholars. Although a catastrophe like the 2014-2015 Ebola outbreak is a rare event, we face crises and challenges every day that require us to organize for resilience: to find creative ways to unearth and repurpose latent resources in order to adapt and even prosper in the face of tumult, trauma, or transformation. -

The Enduring Agony in Sierra Leone & Liberia

Ebola 2013-2016: The Enduring Agony in Sierra Leone & Liberia and The Joy of Helping Patients Survive in Liberia 2014 Daniel R. Lucey MD, MPH Georgetown University Medical Center Law Center O’Neill Institute School of Foreign Service The 28th Annual Dolan Lecture: Nov 12, 2015 Dr. Martin Salia: 1 of > 880 Health Workers in W. Africa Infected with Ebola 2014-15 • This Presentation is Dedicated to Dr. Martin Salia and Colleagues in West Africa • One of > 511 health workers in West Africa who have died due to the Ebola virus in 2014-15 so far. From AIDS 1982 to Ebola 2016: A Career “What is Past is Prologue” (US Nat’l Archives) • AIDS 1982-2002: UCSF, Harvard, DoD, USPHS-NIH/FDA, DC • Anthrax 2001: DC • Smallpox: 2002: DC • SARS 2003: Hong Kong, Toronto, Guangzhou • Avian Flu H5N1 2004-Now: Vietnam, Indonesia, Egypt • Pandemic flu H1N1 2009-2010 USA, Egypt • MERS: 2012-2016: Qatar, Jordan, UAE, Egypt, Bahrain • Avian Flu H7N9 2013-2016: China • Ebola 2013-2016-?ENDEMIC : Guinea • What’s Next in 2015-2016-2017? See Smithsonian Exhibit 2018 23 March 2014: 1st WHO Report of Outbreak starting in Guinea on Border with Liberia & Sierra Leone. By April 7 Spread to Capital Cities for 1st Time RED FLAG!: Ebola in Conakry, Guinea: 3 April The 1st time Ebola Emerged in a Capital City (1976-2014) 12 Ebola FAQs written by Lucey, Hanfling, & Hick 8 April 2014: Sent via HHS Hospital Preparedness Program (HPP) by 15 April URBAN Ebola in West African Capital of Conakry August 8, 2014: WHO Declares Ebola Epidemic “Public Health Emergency International Concern (PHEIC)”* Why was there no earlier meeting of this Advisory Committee, despite WHO report in early April of Ebola in two capital cities for the first time ever? Ebola control measures of isolation, quarantine, and contact tracing never tested to see if they work in a capital city as they had in rural areas. -

What's It Worth to Be Yourself Online? the Genius Of

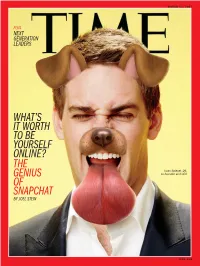

MARCH 13, 2017 PLUS NEXT GENERATION LEADERS WHAT’S IT WORTH TO BE YOURSELF ONLINE? THE Evan Spiegel, 26, GENIUS co-founder and CEO OF SNAPCHAT BY JOEL STEIN time.com VOL. 189, NO. 9 | 2017 4 | From the Editor The View The Features Time Off △ 6 | For the Record Ideas, opinion, What to watch, read, A NASA illustration innovations Why Snapchat’s Snappy see and do of what it would The Brief How an app made up of photos be like to stand on 19 | The difference 49 | Former News from the U.S. and that disappear can be worth tens of the surface of a around the world between free President George Trappist-1 planet billions 9 | speech and hate W. Bush discusses President speech By Joel Stein26 his book of paintings NASA/Getty Images Donald Trump struggles to keep 20 | New book 52 | TV review: Republicans on features a blanket A Perfect Murder? Feud,starring track in Congress history of sleep What the assassination of Kim Jong Susan Sarandonand 10 | Nam, half brother of North Korean Jessica Lange A Senator stands 23 | How tattoos up to Philippine came to illustrate dictator Kim Jong Un, means for 54 | Video games: President Rodrigo women’s liberation the Hermit Kingdom and the world Zelda; Nintendo’s Duterte By Charlie Campbell34 Switch console 23 | Inside Apple’s 12 | Ian Bremmer: futuristic new 56 | Hugh Jackman Tide may be turning headquarters Next Generation Leaders stars in Logan on Europe’s Daily Show host Trevor Noah, populists 24 | What to know 59 | Kristin van about Trappist-1, YouTube star Tyler Oakley, figure Ogtrop on recovery 13 | Alternative the dwarf star skater Nathan Chen and seven from surgery ON THE COVER: facts fact-checked orbited by seven others who are remaking the world TIME photo- 60 | 10 Questions 14 | Earthlike planets By TIME staff38 illustration using James Cameron for author Snapchat filters; remembers actor Chimamanda Photograph Bill Paxton Ngozi Adichie by Andrew Eccles—August TIME (ISSN 0040-781X) is published by Time Inc. -

IHP News 410 : Trump's Budget Blueprint

IHP news 410 : Trump’s budget blueprint (17 March 2017) The weekly International Health Policies (IHP) newsletter is an initiative of the Health Policy unit at the Institute of Tropical Medicine in Antwerp, Belgium. Dear Colleagues, While the quality of governance in the United States is going down (a seemingly endless) drain, the “Lancet Global Health Commission on High-Quality Health Systems in the SDG Era (HQSS)” was launched in Boston early this week. The Commission’s report is scheduled for late 2018. Wonder what kind of world we’ll live in by then - not sure it’ll be one Louis Armstrong would be tempted to sing about, if he were still alive. On Wednesday, another Lancet Commission discussed the “weaponisation” of health care in Syria, a real hellhole for over 6 years now, with health care as one of the prime targets. And then Trump still had to propose his first budget. Against this rapidly worsening global backdrop, you have to wonder what the “theory of change” of Lancet Commissions or even Chris Murray’s fancy GBD visualizations will look like in the era now “formerly known as the SDG/planetary health era”. Indeed, let’s not kid ourselves: even if last week the UN Statistical Commission agreed on a draft resolution on the global indicator framework for the SDGs and on Monday the Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change brought together some experts in London to debate various indicator processes -and the Dutch might disagree - , we live well and truly in the Trump era now, if only because of the sheer weight of the US in the international system. -

Lessons Learned Along the Way

LESSONS LEARNED ALONG THE WAY Sheila Davis, Chief of Clinical Operation, Chief Nursing Officer August 11, 2018 Proverb “a short pithy saying in general use, stating a general truth or piece of advice” http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/proverb 2 Where are you on your journey? 3 “Life is too short for white walls.” --JVS 1997, AIDS Warrior 4 “This world is a harsh place, this world.” Zulu proverb 5 The “Other” • When we can successfully “The other is under our roof or on distance ourselves from the the other side of the globe.” other human beings, see the – Carl Wilkens differences rather than the commonalities, that is when the light goes out on “shared humanness”. • Dehumanizing individuals, communities or entire populations creates an environment that fosters and even celebrates cruelty and violence. 6 "The worst sin towards our fellow creatures is not to hate them, but to be indifferent to them: That's the essence of inhumanity." --George Bernard Shaw Bearing Witness A privileged, sacred role with the utmost responsibility to the person/people involved as well as to society as a whole. 8 Lesson One • Be open to the journey. • Your teachers are everywhere. • Find your people. • Listen intently to those who are impacted the most. • Use your VOICE 9 Partners In Health • . “It is in the shelter of each other that the people live.” --Irish Proverb Where We Work Our Mission PIH delivers high- quality health care in some of the world’s poorest communities. By pushing the boundaries of what’s possible in health care, PIH has a global impact.