Embedded Judicial Autonomy: How Ngos and Public Opinion Influence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vice President's Power and Role in Indonesian Government Post Amendment 1945 Constitution

Al WASATH Jurnal Ilmu Hukum Volume 1 No. 2 Oktober 2020: 61-78 VICE PRESIDENT'S POWER AND ROLE IN INDONESIAN GOVERNMENT POST AMENDMENT 1945 CONSTITUTION Roziqin Guanghua Law School, Zhejiang University, China Email: [email protected] Abstract Politicians are fighting over the position of Vice President. However, after becoming Vice President, they could not be active. The Vice President's role is only as a spare tire. Usually, he would only perform ceremonial acts. The exception was different when the Vice President was Mohammad Hata and Muhammad Jusuf Kalla. Therefore, this paper will question: What is the position of the President in the constitutional system? What is the position of the Vice President of Indonesia after the amendment of the 1945 Constitution? Furthermore, how is the role sharing between the President and Vice President of Indonesia? This research uses the library research method, using secondary data. This study uses qualitative data analysis methods in a prescriptive-analytical form. From the research, the writer found that the President is assisted by the Vice President and ministers in carrying out his duties. The President and the Vice President work in a team of a presidential institution. From time to time, the Indonesian Vice President's position has always been the same to assist the President. The Vice President will replace the President if the President is permanently unavailable or temporarily absent. With the Vice President's position who is directly elected by the people in a pair with the President, he/she is a partner, not subordinate to the President. -

Sudargo Gautama and the Development of Indonesian Public Order: a Study on the Application of Public Order Doctrine in a Pluralistic Legal System

Sudargo Gautama and the Development of Indonesian Public Order: A Study on the Application of Public Order Doctrine in a Pluralistic Legal System Yu Un Oppusunggu A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2015 Reading Committee: John O. Haley, Chair Michael E. Townsend Beth E. Rivin Program Authorized to Offer Degree School of Law © Copyright 2015 Yu Un Oppusunggu ii University of Washington Abstract Sudargo Gautama and the Development of Indonesian Public Order: A Study on the Application of Public Order Doctrine in a Pluralistic Legal System Yu Un Oppusunggu Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor John O. Haley School of Law A sweeping proviso that protects basic or fundamental interests of a legal system is known in various names – ordre public, public policy, public order, government’s interest or Vorbehaltklausel. This study focuses on the concept of Indonesian public order in private international law. It argues that Indonesia has extraordinary layers of pluralism with respect to its people, statehood and law. Indonesian history is filled with the pursuit of nationhood while protecting diversity. The legal system has been the unifying instrument for the nation. However the selected cases on public order show that the legal system still lacks in coherence. Indonesian courts have treated public order argument inconsistently. A prima facie observation may find Indonesian public order unintelligible, and the courts have gained notoriety for it. This study proposes a different perspective. It sees public order in light of Indonesia’s legal pluralism and the stages of legal development. -

Redalyc.Democratization and TNI Reform

UNISCI Discussion Papers ISSN: 1696-2206 [email protected] Universidad Complutense de Madrid España Marbun, Rico Democratization and TNI reform UNISCI Discussion Papers, núm. 15, octubre, 2007, pp. 37-61 Universidad Complutense de Madrid Madrid, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=76701504 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative UNISCI Discussion Papers, Nº 15 (Octubre / October 2007) ISSN 1696-2206 DEMOCRATIZATIO A D T I REFORM Rico Marbun 1 Centre for Policy and Strategic Studies (CPSS), Indonesia Abstract: This article is written to answer four questions: what kind of civil-military relations is needed for democratization; how does military reform in Indonesia affect civil-military relations; does it have a positive impact toward democratization; and finally is the democratization process in Indonesia on the right track. Keywords: Civil-military relations; Indonesia. Resumen: Este artículo pretende responder a cuatro preguntas: qué tipo de relaciones cívico-militares son necesarias para la democratización; cómo afecta la reforma militar en Indonesia a las relaciones cívico-militares; si tiene un impacto positivo en la democratización; y finalmente, si el proceso de democratización en Indonesia va por buen camino. Palabras clave: relaciones cívico-militares; Indonesia. Copyright © UNISCI, 2007. The views expressed in these articles are those of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect the views of UNISCI. Las opiniones expresadas en estos artículos son propias de sus autores, y no reflejan necesariamente la opinión de U*ISCI. -

The Politics of Military Reform in Post-Suharto Indonesia: Elite Conflict, Nationalism, and Institutional Resistance

Policy Studies 23 The Politics of Military Reform in Post-Suharto Indonesia: Elite Conflict, Nationalism, and Institutional Resistance Marcus Mietzner East-West Center Washington East-West Center The East-West Center is an internationally recognized education and research organization established by the U.S. Congress in 1960 to strengthen understanding and relations between the United States and the countries of the Asia Pacific. Through its programs of cooperative study, training, seminars, and research, the Center works to promote a stable, peaceful, and prosperous Asia Pacific community in which the United States is a leading and valued partner. Funding for the Center comes from the U.S. government, private foundations, individuals, cor- porations, and a number of Asia Pacific governments. East-West Center Washington Established on September 1, 2001, the primary function of the East- West Center Washington is to further the East-West Center mission and the institutional objective of building a peaceful and prosperous Asia Pacific community through substantive programming activities focused on the theme of conflict reduction, political change in the direction of open, accountable, and participatory politics, and American understanding of and engagement in Asia Pacific affairs. The Politics of Military Reform in Post-Suharto Indonesia: Elite Conflict, Nationalism, and Institutional Resistance Policy Studies 23 ___________ The Politics of Military Reform in Post-Suharto Indonesia: Elite Conflict, Nationalism, and Institutional Resistance _____________________ Marcus Mietzner Copyright © 2006 by the East-West Center Washington The Politics of Military Reform in Post-Suharto Indonesia: Elite Conflict, Nationalism, and Institutional Resistance by Marcus Mietzner ISBN 978-1-932728-45-3 (online version) ISSN 1547-1330 (online version) Online at: www.eastwestcenterwashington.org/publications East-West Center Washington 1819 L Street, NW, Suite 200 Washington, D.C. -

Reforming Group Legal Personhood in Indonesian Land Law: Towards Equitable Land Rights for Traditional Customary Communities

Reforming Group Legal Personhood in Indonesian Land Law: Towards Equitable Land Rights for Traditional Customary Communities Lilis Mulyani ORCID ID 0000-0002-1290-378X Doctor of Philosophy September 2020 Faculty of Law The University of Melbourne Submitted in total fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Thesis Abstract An adequate definition of group legal personhood (that is, a rights and obligation- holding personality) in Indonesian law is essential if there is to be equal land rights distribution. The present unclear definition of groups in the law as legal persons, coupled with uncoordinated and fragmented government policies, means that land- related decision-making usually operates only for the benefit of persons seen by the law as an ideal legal subject. In this thesis, I focus on 'person' in the sense of a group of individuals that associate as a single unified entity. In Indonesia and in general legal doctrine, the lack of clarity in the definition of ‘legal person’ has resulted in traditional customary (adat) groups and their customary land title being excluded and this vulnerable to marginalisation and land expropriation. This has given rise to much debate about which groups can be said to have a legal personality as bearers of rights and obligation, and why. The thesis aims: to understand the core concept of a group as a legal or juridical person; investigate how decisions on land rights are made by the Indonesian government; how traditional customary (adat) groups themselves choose to be recognised; and how such distributions could be reformed to better protect adat groups. Two case studies on specific policies related to the asserting of the customary communal land title (hak ulayat) are reviewed, covering the background of decisions on land rights entitlement (socio-legal and political), the process for distribution, and the consequences of the policies chosen. -

When the Constitutionality of the Revised Corruption Eradication Commission (Kpk) Law Is Questioned

Number 160 • June 2020 i 5th and 6th Floor, Constitutional Court Building Jl. Medan Merdeka Barat No. 6 Jakarta Pusat Lantai 5 dan 6 Gedung Mahkamah Konstitusi Jl. Medan Merdeka Barat No. 6 Jakarta Pusat ii Number 160 • June 2020 Number 160 • June 2020 DIRECTING BOARD: Editorial Greetings Anwar Usman • Aswanto • Arief Hidayat Enny Nurbaningsih • Wahiduddin Adams he Constitutional Magazine released in June 2020 provides a variety of Suhartoyo • Manahan MP Sitompul interesting information through distinctive rubrics. The news that is in our Saldi Isra • Daniel Yusmic Pancastaki Foekh Tspotlight is the development of the review of Law Number 19 of 2019 DIRECTOR: concerning the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK Law) for Cases Number M. Guntur Hamzah 62, 70, 71, 73, 59, 77, 79 / PUU-XVII / 2019. Although it has not been decided yet, EDITOR IN CHIEF: the review of this law contains various interesting and important aspects for the Heru Setiawan public. Therefore, the editorial team determined this news as the Main Report. Petitioners for reviewing the KPK Law come from various professions. DEPUTY EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: There are advocates who are of the opinion that the process of ratifying the KPK Fajar Laksono Suroso Law amendments is not in accordance with the applicable laws and regulations. MANAGING EDITOR: Because at the plenary session the number of People's Representative Council Mutia Fria Darsini members who attended was 80, at least less than half of the total number of EDITORIAL SECRETARY: People's Representative Council members. Changes to the KPK Law were carried Tiara Agustina out in secret and discussed in People's Representative Council meetings in a EDITOR: relatively short period of time. -

Amending the Constitution of Year 1945 (A Proposition to Strengthen the Power of DPD and Judiciary)

The Idea of (Re)Amending the Constitution of Year 1945 (A Proposition to Strengthen the Power of DPD and Judiciary) Ni’matul Huda Fakultas Hukum UII Yogyakarta e-mail: [email protected] Abstract The urgency of re-amending the Constitution of Year 1945 is due to the idea of enhancing the previous amendment, that is, to attain better administrative governance in Indonesia. As it goes without saying that the Constitution of Year 1945 is sacred, the amendment itself should be a well thought-out process that requires thorough and deep considerations and certainly cannot be taken carelessly. Keywords: Amendment of The Constitution of Year 1945, The Regional Representatives Council (DPD), The Authority of Judiciary. Introduction At the beginning of year 2008, the Government and the House of Representatives agreed to set up the fifth amendment to the Constitution of Year 1945 by immediately formed a national committee. The agreement was made in the consultative meeting in the State Palace, Jakarta, Friday January 25, 2008. The new Constitution is expected to be used by the new government of 2009 general election. The President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono’s and the House of Representatives’ proposal to form a committee to set up the fifth amendment to the Constitution of Year 1945 created various reactions from the people. Some members of MPR and Constitution Forum disagree to the proposal saying that it is MPR who has the authority to establish such committee and it is really not within the presidential domain.1 On the other hand, some members of DPD and state administrations experts support the proposal.2 Normatively, it is MPR that has the authority to amend the Constitution of Year 1945, therefore it would deem more appropriate if MPR were to establish the national committee. -

The Rise and Fall of Historic Chief Justices: Constitutional Politics and Judicial Leadership in Indonesia

Washington International Law Journal Volume 25 Number 3 Asian Courts and the Constitutional Politics of the Twenty-First Century 6-1-2016 The Rise and Fall of Historic Chief Justices: Constitutional Politics and Judicial Leadership in Indonesia Stefanus Hendrianto Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wilj Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, and the Judges Commons Recommended Citation Stefanus Hendrianto, The Rise and Fall of Historic Chief Justices: Constitutional Politics and Judicial Leadership in Indonesia, 25 Wash. L. Rev. 489 (2016). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wilj/vol25/iss3/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at UW Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington International Law Journal by an authorized editor of UW Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Compilation © 2016 Washington International Law Journal Association THE RISE AND FALL OF HISTORIC CHIEF JUSTICES: CONSTITUTIONAL POLITICS AND JUDICIAL LEADERSHIP IN INDONESIA By Stefanus Hendrianto † Abstract : In the decade following its inception, the Indonesian Constitutional Court has marked a new chapter in Indonesian legal history, one in which a judicial institution can challenge the executive and legislative branches. This article argues that judicial leadership is the main contributing factor explaining the emergence of judicial power in Indonesia. This article posits that the newly established Indonesian Constitutional Court needed a strong and skilled Chief Justice to build the institution because it had insufficient support from political actors. As the Court lacked a well- established tradition of judicial review, it needed a visionary leader who could maximize the structural advantage of the Court. -

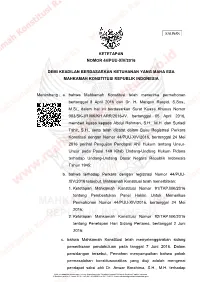

44/Puu-Xiv/2016

SALINAN KETETAPAN NOMOR 44/PUU-XIV/2016 DEMI KEADILAN BERDASARKAN KETUHANAN YANG MAHA ESA MAHKAMAH KONSTITUSI REPUBLIK INDONESIA Menimbang : a. bahwa Mahkamah Konstitusi telah menerima permohonan bertanggal 8 April 2016 dari Dr. H. Marigun Rasyid, S.Sos., M.Si., dalam hal ini berdasarkan Surat Kuasa Khusus Nomor 003/SK-JR.MK/KH.ARR/2016-IV, bertanggal 05 April 2016, memberi kuasa kepada Abdul Rahman, S.H., M.H. dan Suriadi Tahir, S.H., serta telah dicatat dalam Buku Registrasi Perkara Konstitusi dengan Nomor 44/PUU-XIV/2016, bertanggal 24 Mei 2016 perihal Pengujian Pendapat Ahli Hukum tentang Unsur- Unsur pada Pasal 149 Kitab Undang-Undang Hukum Pidana terhadap Undang-Undang Dasar Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 1945; b. bahwa terhadap Perkara dengan registrasi Nomor 44/PUU- XIV/2016 tersebut, Mahkamah Konstitusi telah menerbitkan: 1. Ketetapan Mahkamah Konstitusi Nomor 91/TAP.MK/2016 tentang Pembentukan Panel Hakim Untuk Memeriksa Permohonan Nomor 44/PUU-XIV/2016, bertanggal 24 Mei 2016; 2. Ketetapan Mahkamah Konstitusi Nomor 92/TAP.MK/2016 tentang Penetapan Hari Sidang Pertama, bertanggal 2 Juni 2016; c. bahwa Mahkamah Konstitusi telah menyelenggarakan sidang pemeriksaan pendahuluan pada tanggal 7 Juni 2016. Dalam persidangan tersebut, Pemohon menyampaikan bahwa pokok permasalahan konstitusionalitas yang diuji adalah mengenai pendapat saksi ahli Dr. Anwar Borahima, S.H., M.H. terhadap Untuk mendapatkan salinan resmi, hubungi Kepaniteraan dan Sekretariat Jenderal Mahkamah Konstitusi Republik Indonesia Jl. Merdeka Barat No.6, Jakarta -

Bab Ii Pemikiran Mahfud Md Dalam Memaknai Konstitusi Dan Demokrasi

BAB II PEMIKIRAN MAHFUD MD DALAM MEMAKNAI KONSTITUSI DAN DEMOKRASI A. Biografi Mahfud MD 1) Asal Nama Mahfud MD Mahfud MD lahir di Sampang Madura pada tanggal 13 Mei 1957. Tepatnya di Desa Rapah, Kecamatan Omben. Kabupaten Sampang. Ayahnya bernama Mahmodin, ibunya bernama Khadijah. 1 Sebenarnya Mahmodin dan Khadijah berasal dari daerah Pegantenan. Pamekasan, tetapi karena Mahmodin bekerja sebagai pegawai negeri sipil di kantor pemerintah daerah, maka tempat tugasnya sering berpindah- pindah sesuai dengan penugasan oleh pemerintah. Saudara- saudara, Mahfud MD yang berjumlah 7 orang dilahirkan di tempat yang berbeda-beda. Saat diangkat menjadi pegawai negeri sipil, Mahmodin, di beri nama baru menjadi Mahmodin 1 Masduki Baidlowi dan Rizal Mustari, Mafud MD Bersih dan Membersihkan, (Jakarta: Murai Kencana, 2013), h.37. 29 30 alias Emmo Prawirotruno. Awal-awal kemerdekaan, sebelum ada badan administrasi kepegawaian negara sehingga siapa saja yang ingin menjadi pegawai tinggal menyebut nama atau menerima nama yang diberikan oleh atasannya. Mahmodin hanyalah lulusan sekolah rakyat zaman Belanda yang tamat hanya sampai kelas 5. Tetapi Mahfud MD mengatakan, tulisan ayahnya yang hanya lulus kelas 5 sangatlah bagus. Pada saat Mahmodin bertitugas di kecamatan Omben, Kabupaten Sampang itkah Mhafud MD di lahirkan. Ketika dilahirkan nama yang diberikan oleh ayahnya adalah Muhammad Mahfud saja, tidak ada inisial MD di belakangnya. Ketika Mahfud MD berusia sekitar dua bulan, ayahnya pindah tugas ke Pameksaan, tepatnya di kecamatan Waru, yakni 30 km sebelah utara kota Pameksaan. Di Waru inilah masa kecil Mahfud MD dilewati sampai berumur 12 tahun. Mahmodin dikaruniai 9 orang putera dan putri tetapi yang hidup hanya ada 7 orang yaitu Dhaifatun (Mbak Ifah), Maihasanah (Mbak Mai), Zahrotun (Mbak Zah), kemudian Mohammad Mahfud (Mahfud MD), Siti Honainah (Dik Ina), Achmad Subki (Dik Uki), dan 31 Siti Marwiyah (Dik Yat). -

Protecting Economic and Social Rights in a Constitutionally Strong Form of Judicial Review: the Case of Constitutional Review by the Indonesian Constitutional Court

Protecting Economic and Social Rights in a Constitutionally Strong Form of Judicial Review: The Case of Constitutional Review by the Indonesian Constitutional Court Andy Omara A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2017 Reading Committee: Beth E. Rivin, Chair Hugh D. Spitzer, Co-Chair Walter J. Walsh Mark E. Cammack Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Law ©Copyright 2017 Andy Omara University of Washington Abstract Protecting Economic and Social Rights in a Constitutionally Strong form of Judicial Review: The Case of Constitutional Review by the Indonesian Constitutional Court Andy Omara Chair and Co-Chair of the Supervisory Committee Professor Beth E. Rivin and Professor Hugh D. Spitzer School of Law The 1999-2002 constitutional amendments to Indonesia’s Constitution inserted some important features of a modern constitution. These include the introduction of a comprehensive human rights provision and a new constitutional court. This dissertation focuses on these two features and aims to understand the roles of this new court in protecting economic and social rights (ES rights). It primarily analyzes (1) factors that explain the introduction of a constitutional court in Indonesia, (2) the Court’s approaches in conducting judicial review of ES rights cases, (3) Factors that were taken into account by the Court when it decided cases on ES rights, and (4) the lawmakers’ response toward the Court’s rulings on ES rights. This dissertation reveals that, first, the introduction of a constitutional court in Indonesia can be best explained by multiple contributing factors –not a single factor. -

PUTUSAN Nomor 98/PUU-XII/2014 DEMI KEADILAN

PUTUSAN Nomor 98/PUU-XII/2014 DEMI KEADILAN BERDASARKAN KETUHANAN YANG MAHA ESA MAHKAMAH KONSTITUSI REPUBLIK INDONESIA [1.1] Yang mengadili perkara konstitusi pada tingkat pertama dan terakhir, menjatuhkan putusan dalam perkara pengujian Undang-Undang tanpa nomor Tahun 2014 tentang Pemilihan Kepala Daerah terhadap Undang-Undang Dasar Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 1945, yang diajukan oleh: [1.2] Nama : Prof. Dr. O.C. Kaligis, S.H., M.H. Selaku Ketua Mahkamah Partai Nasdem Alamat : Jalan Majapahit Nomor 18-20, Kompleks Majapahit Permai Blok B 122-123, Jakarta Pusat Dalam hal ini berdasarkan Surat Kuasa Nomor 339/SK.IX/2014 bertanggal 29 September 2014 memberi kuasa kepada Dr. Purwaning M. Yanuar, S.H., M.CL., CN., Dr. Rico Pandeirot, S.H., LL.M., R. Andika Yoedistira, S.H., M.H., Rocky L. Kawilarang, S.H., Gajah Bharata Ramedhan, S.H., LL.M., Desyana, S.H., M.H., Nadya Helida, S.H., M.H., Mety Rahmawati, S.H., Sarah Chairunnisa, S.H., Yurinda Tri Achyuni, S.H., LL.M., Stephanie Tasja Dammee, S.H., Jeffy Katio, S.H., dan Nadia Saphira Ganie, S.H., LL.M., Advokat/Pengacara, berkantor di Kantor Advokat, O.C. KALIGIS & ASSOCIATES, beralamat di Jalan Majapahit Nomor 18-20, Kompleks Majapahit Permai Blok B. 122-123, Jakarta Pusat, bertindak untuk dan atas nama pemberi kuasa; Selanjutnya disebut sebagai -------------------------------------------------------- Pemohon; [1.3] Membaca permohonan Pemohon; Mendengar keterangan Pemohon; Salinan putusan ini tidak untuk dan tidak dapat dipergunakan sebagai rujukan resmi atau alat bukti. Untuk informasi lebih lanjut, hubungi Kepaniteraan dan Sekretariat Jenderal Mahkamah Konstitusi Republik Indonesia, Jl. Merdeka Barat No.6, Jakarta 10110, Telp.