The Poetic Architecture of Belfast

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Young Citizen Volunteers 10Th September 1912 the Young Citizen Volunteers

Young Citizen Volunteers 10th September 1912 The Young Citizen Volunteers Introduction Lance-Corporal Walter Ferguson , aged 24, of 14th Royal Irish Rifles died (according to the website of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission) on 8 July 1916, although the marble tablet erected in All Saints Parish Church, University Street, Belfast, by his sorrowing father states he was ‘killed in action on 1 July 1916’. It seems very probable that he died a slow and possibly painful death from wounds sustained on 1 July and in captivity because he is buried in Caudry Old Communal Cemetery which was then in German-held territory. Walter’s family did not learn of his death immediately. They sought news of him in the Belfast Evening Telegraph of 18 July 1916: No news has been received regarding L’ce Corporal Walter Ferguson (14596) YCVs since before the Big Push and his relatives, who reside at 2 Collingwood Road, Belfast, are very anxious about him and would be grateful for any information. In civil life he was a bookbinder … News from the Front often trickled home agonizingly slowly. For example, the Northern Whig of 27 July 1916 reveals another Belfast family anxious to learn the fate of their son, also a lance-corporal in 14th Royal Irish Rifles and a member of the YCV: Revd John Pollock (St Enoch’s Church), 7 Glandore Park, Antrim Road, will be glad to receive any information regarding his son Lance-corporal Paul G Pollock, scout, Royal Irish Rifles (YCV), B Company, who had engaged in the advance of the Ulster Division on 1st July last, and has been ‘missing’ since that date. -

Architecture, Urbanisme & Utopie

Architecture, urbanisme & Utopie La tour de Babel était selon la Genèse une tour que souhaitaient construire les hommes pour atteindre le ciel. Selon les traditions judéo-chrétiennes, c'est Nemrod, le « roi-chasseur » régnant sur les descendants de Noé, qui eut l'idée de construire à Babel (Babylone) une tour assez haute pour que son sommet atteigne le ciel. Descendants de Noé, ils représentaient donc l'humanité entière et étaient censés tous parler la même et unique langue sur Terre, une et une seule langue adamique. Pour contrecarrer leur projet qu'il jugeait plein d'orgueil, Dieu multiplia les langues afin que les hommes ne se comprissent plus. Ainsi la construction ne put plus avancer, elle s'arrêta, et les hommes se dispersèrent sur la terre. Cette histoire est parfois vue comme une tentative de réponse des hommes au mystère apparent de l'existence de plusieurs langues, mais est aussi le véhicule d'un enseignement d'ordre moral : elle illustre les dangers de vouloir se placer à l'égal de Dieu, de le défier par notre recherche de la connais- sance, mais aussi la nécessité qu'a l'humanité de se parler, de se comprendre pour réaliser de grands projets, ainsi que le risque de voir échouer ces projets quand chaque groupe de spécialistes se met à parler le seul jargon de sa discipline. Ce récit peut aussi être vu comme une métaphore du malen- tendu humain; où contrairement aux animaux, les êtres humains ne se comprennent pas par des signes univoques, mais bien par l'équivocité du signifiant. Les récits de constructions que les hommes tentaient d'élever jusqu'au ciel ont depuis longtemps mar- qué les esprits, source d’inspiration pour bon nombre d’écrivains et d’artistes. -

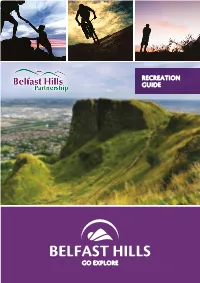

Recreation Guide

RECREATION GUIDE GO EXPLORE Permit No. 70217 Based upon the Ordnance Survey of Northern Ireland Map with the permission of the controller of her Majesty’s Stationery Office © Crown Copyright 2007 A STRIKING VISUAL BOUNDARY The Belfast Hills make up the summits of the west and north of Belfast city. They form a striking visual boundary that sets them apart from the urban populace living in the valley below. The closeness to such a large population means the hills are becoming increasingly popular among people eager to access them for recreational activities. The public sites that are found across the hills certainly offer fantastic opportunities for organised and informal recreation. The Belfast Hills Partnership was formed in 2004 by a wide range of interest groups seeking to encourage better management of the hills in the face of illegal waste, degradation of landscape and unmanaged access. Our role in recreation is to work with our partners to improve facilities and promote sustainable use of the hills - sensitive to traditional ways of farming and land management in what is a truly outstanding environment. Over the coming years we will work in partnership with those who farm, manage or enjoy the hills to develop recreation in ways which will sustain all of these uses. 4 Belfast Hills • Introduction ACTIVITIES Walking 6 Cycling 10 Running 12 Geocaching 14 Orienteering 16 Other Activities 18 Access Code 20 Maps 21 Belfast Hills • Introduction 5 With well over half a million hikes taken every year, walking is the number one recreational activity in the Belfast Hills. A wide range of paths and routes are available - from a virtually flat 400 metres path at Carnmoney Hill pond, to the Divis Boundary route stretching almost seven miles (11km) across blanket bog and upland heath with elevations of 263m to 377m high. -

The Great War in Irish Poetry

Durham E-Theses Creation from conict: The Great War in Irish poetry Brearton, Frances Elizabeth How to cite: Brearton, Frances Elizabeth (1998) Creation from conict: The Great War in Irish poetry, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/5042/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Creation from Conflict: The Great War in Irish Poetry The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without the written consent of the author and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Frances Elizabeth Brearton Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D Department of English Studies University of Durham January 1998 12 HAY 1998 ABSTRACT This thesis explores the impact of the First World War on the imaginations of six poets - W.B. -

Irish Studies Around the World – 2020

Estudios Irlandeses, Issue 16, 2021, pp. 238-283 https://doi.org/10.24162/EI2021-10080 _________________________________________________________________________AEDEI IRISH STUDIES AROUND THE WORLD – 2020 Maureen O’Connor (ed.) Copyright (c) 2021 by the authors. This text may be archived and redistributed both in electronic form and in hard copy, provided that the author and journal are properly cited and no fee is charged for access. Introduction Maureen O’Connor ............................................................................................................... 240 Cultural Memory in Seamus Heaney’s Late Work Joanne Piavanini Charles Armstrong ................................................................................................................ 243 Fine Meshwork: Philip Roth, Edna O’Brien, and Jewish-Irish Literature Dan O’Brien George Bornstein .................................................................................................................. 247 Irish Women Writers at the Turn of the 20th Century: Alternative Histories, New Narratives Edited by Kathryn Laing and Sinéad Mooney Deirdre F. Brady ..................................................................................................................... 250 English Language Poets in University College Cork, 1970-1980 Clíona Ní Ríordáin Lucy Collins ........................................................................................................................ 253 The Theater and Films of Conor McPherson: Conspicuous Communities Eamon -

HEANEY, SEAMUS, 1939-2013. Seamus Heaney Papers, 1951-2004

HEANEY, SEAMUS, 1939-2013. Seamus Heaney papers, 1951-2004 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Collection Stored Off-Site All or portions of this collection are housed off-site. Materials can still be requested but researchers should expect a delay of up to two business days for retrieval. Descriptive Summary Creator: Heaney, Seamus, 1939-2013. Title: Seamus Heaney papers, 1951-2004 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 960 Extent: 49.5 linear feet (100 boxes), 3 oversized papers boxes (OP), and AV Masters: 1 linear foot (2 boxes) Abstract: Personal papers of Irish poet Seamus Heaney consisting mostly of correspondence, as well as some literary manuscripts, printed material, subject files, photographs, audiovisual material, and personal papers from 1951-2004. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on access Collection stored off-site. Researchers must contact the Rose Library in advance to access this collection. Special restrictions apply: Use copies have not been made for audiovisual material in this collection. Researchers must contact the Rose Library at least two weeks in advance for access to these items. Collection restrictions, copyright limitations, or technical complications may hinder the Rose Library's ability to provide access to audiovisual material. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction All requests subject to limitations noted in departmental policies on reproduction. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. Copies supplied may not be copied for others or otherwise distributed without prior consent of the holding repository. -

Interview: Michael Longley and Jody Allen Randolph

Colby Quarterly Volume 39 Issue 3 September Article 12 9-1-2003 Interview: Michael Longley and Jody Allen Randolph Jody AllenRandolph Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Quarterly, Volume 39, no.3, September 2003, p.294-308 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. AllenRandolph: Interview: Michael Longley and Jody Allen Randolph Interview: Michael Longley and Jody AllenRandolph You are variously described as a nature poet, a love poet, a classical poet, a war poet, a political poet. Do any of these tags feel closer to home than others? I don't care for pigeonholing. I hope there are overlappings, the nature poetry fertilizing the war poetry, and so on. Advancing on a number of fronts at the same time looks like a good idea: if there's a freeze-up at points along the line, you can trickle forward somewhere else. Love poetry is at the core of the enterprise-the hub of the wheel from which the other preoccupations radiate like spokes. In my next collection Snow Water there will be eleven new love poems. I wouldn't mind being remembered as a love poet, a sexagenarian love poet. I occasionally write poems about war-as a non-combatant. Only the soldier poets I revere such as Wilfred Owen and Keith Douglas produce what I would call proper war poetry. It's presun1ptuouS to call oneself a poet. -

Statute Law Revision Act 2012 ———————— Arran

Click here for Explanatory Memorandum ———————— Number 19 of 2012 ———————— STATUTE LAW REVISION ACT 2012 ———————— ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS Section 1. Definitions. 2. General statute law revision repeal and saver. 3. Specific repeals. 4. Assignment of short titles. 5. Miscellaneous amendments to short titles. 6. Savings. 7. Amendment of Adaptation of Enactments Act 1922. 8. Short title and collective citations. SCHEDULE 1 ACTS SPECIFICALLY RETAINED PART 1 Irish Private Acts 1751 to 1800 PART 2 Private Acts of Great Britain 1751 to 1800 PART 3 United Kingdom Private Acts 1801 to 1922 PART 4 United Kingdom Local and Personal Acts 1851 to 1922 1 [No. 19.]Statute Law Revision Act 2012. [2012.] SCHEDULE 2 ACTS SPECIFICALLY REPEALED PART 1 Irish Private Acts 1751 to 1800 PART 2 Private Acts of Great Britain 1751 to 1800 PART 3 United Kingdom Private Acts 1801 to 1922 PART 4 United Kingdom Local and Personal Acts 1851 to 1922 ———————— Acts Referred to Adaptation of Charters Act 1926 1926, No. 6 Adaptation of Enactments Act 1931 1931, No. 34 Adaptation of Enactments Act 1922 1922, No. 2 Constitution (Consequential Provisions) Act 1937 1937, No. 40 Drainage and Improvement of Lands Supplemental Act (Ireland) 1868 31 & 32 Vict., c. clvii Drainage and Improvement of Lands Supplemental Act (Ireland) 1868 31 & 32 Vict., c. clviii Drainage and Improvement of Lands Supplemental Act (Ireland) 1873 36 & 37 Vict., c. xv Interpretation Act 2005 2005, No. 23 Local Government Act 2001 2001, No. 37 Lough Swilly and Lough Foyle Reclamation Acts Amend- ment 1853 16 & 17 Vict., c. lxv Short Titles Acts 1896 to 2009 Statute Law Revision Act 2007 2007, No. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses 'A forest of intertextuality' : the poetry of Derek Mahon Burton, Brian How to cite: Burton, Brian (2004) 'A forest of intertextuality' : the poetry of Derek Mahon, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/1271/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk "A Forest of Intertextuality": The Poetry of Derek Mahon Brian Burton A copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Submitted as a thesis for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Durham Department of English Studies 2004 1 1 JAN 2u05 I Contents Contents I Declaration 111 Note on the Text IV List of Abbreviations V Introduction 1 1. 'Death and the Sun': Mahon and Camus 1.1 'Death and the Sun' 29 1.2 Silence and Ethics 43 1.3 'Preface to a Love Poem' 51 1.4 The Terminal Democracy 59 1.5 The Mediterranean 67 1.6 'As God is my Judge' 83 2. -

The Culture of Wikipedia

Good Faith Collaboration: The Culture of Wikipedia Good Faith Collaboration The Culture of Wikipedia Joseph Michael Reagle Jr. Foreword by Lawrence Lessig The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. Web edition, Copyright © 2011 by Joseph Michael Reagle Jr. CC-NC-SA 3.0 Purchase at Amazon.com | Barnes and Noble | IndieBound | MIT Press Wikipedia's style of collaborative production has been lauded, lambasted, and satirized. Despite unease over its implications for the character (and quality) of knowledge, Wikipedia has brought us closer than ever to a realization of the centuries-old Author Bio & Research Blog pursuit of a universal encyclopedia. Good Faith Collaboration: The Culture of Wikipedia is a rich ethnographic portrayal of Wikipedia's historical roots, collaborative culture, and much debated legacy. Foreword Preface to the Web Edition Praise for Good Faith Collaboration Preface Extended Table of Contents "Reagle offers a compelling case that Wikipedia's most fascinating and unprecedented aspect isn't the encyclopedia itself — rather, it's the collaborative culture that underpins it: brawling, self-reflexive, funny, serious, and full-tilt committed to the 1. Nazis and Norms project, even if it means setting aside personal differences. Reagle's position as a scholar and a member of the community 2. The Pursuit of the Universal makes him uniquely situated to describe this culture." —Cory Doctorow , Boing Boing Encyclopedia "Reagle provides ample data regarding the everyday practices and cultural norms of the community which collaborates to 3. Good Faith Collaboration produce Wikipedia. His rich research and nuanced appreciation of the complexities of cultural digital media research are 4. The Puzzle of Openness well presented. -

Michael Longley's Poetry of the Elements in Snow Water

Estudios Irlandeses , Number 6, 2011, pp. 1-7 __________________________________________________________________________________________ AEDEI Michael Longley’s Poetry of the Elements in Snow Water Elisabeth Delattre Université d’Artois Copyright (c) 2011 by Elisabeth Delattre. This text may be archived and redistributed both in electronic form and in hard copy, provided that the author and journal are properly cited and no fee is charged for access. Abstract. Nature has always played a major part in Michael Longley’s poetry, for ecological reasons but also because of the feeling of empathy involved, as Snow Water published in 2004 testifies. This analysis will rely essentially on Gaston Bachelard’s phenomenological approach which deals with the way human reverie on matter governs poetic writing as the sensitory experience of the world. Key words. poetry, nature, elements, symbols, imagination Resumen. La naturaleza ha jugado siempre un papel importante en la poesía de Michael Longley, por razones ecológicas pero también por el sentimiento de empatía que comporta, tal como pone de manifiesto el volumen Snow Water publicado en 2004. El siguiente análisis usará esencialmente la aproximación fenomenológica de Gaston Bachelard, que se basa en la manera en que la ensoñación humana en torno a la materia gobierna la escritura poética en tanto que experiencia sensorial del mundo. Palabras clave. Poesía, naturaleza, elementos, símbolos, imaginación. Le meilleur parti à prendre est donc de considérer toutes choses comme inconnues, et de se promener ou de s’étendre sous bois ou sur l’herbe, et de reprendre tout du début (Francis Ponge, Le Parti pris des choses). Air, soil, water, fire – those are the words, I myself am a word with them – my qualities interpenetrate with theirs (Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass). -

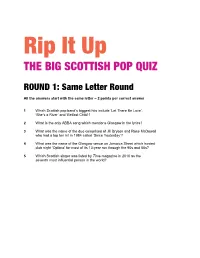

Big Scottish Pop Quiz Questions

Rip It Up THE BIG SCOTTISH POP QUIZ ROUND 1: Same Letter Round All the answers start with the same letter – 2 points per correct answer 1 Which Scottish pop band’s biggest hits include ‘Let There Be Love’, ‘She’s a River’ and ‘Belfast Child’? 2 What is the only ABBA song which mentions Glasgow in the lyrics? 3 What was the name of the duo comprised of Jill Bryson and Rose McDowall who had a top ten hit in 1984 called ‘Since Yesterday’? 4 What was the name of the Glasgow venue on Jamaica Street which hosted club night ‘Optimo’ for most of its 13-year run through the 90s and 00s? 5 Which Scottish singer was listed by Time magazine in 2010 as the seventh most influential person in the world? ROUND 1: ANSWERS 1 Simple Minds 2 Super Trouper (1st line of 1st verse is “I was sick and tired of everything/ When I called you last night from Glasgow”) 3 Strawberry Switchblade 4 Sub Club (address is 22 Jamaica Street. After the fire in 1999, Optimo was temporarily based at Planet Peach and, for a while, Mas) 5 Susan Boyle (She was ranked 14 places above Barack Obama!) ROUND 6: Double or Bust 4 points per correct answer, but if you get one wrong, you get zero points for the round! 1 Which Scottish New Town was the birthplace of Indie band The Jesus and Mary Chain? a) East Kilbride b) Glenrothes c) Livingston 2 When Runrig singer Donnie Munro left the band to stand for Parliament in the late 1990s, what political party did he represent? a) Labour b) Liberal Democrat c) SNP 3 During which month of the year did T in the Park music festival usually take