Belfast Leases, Lord Donegall, and the Incumbered Estates Act, 1849*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Young Citizen Volunteers 10Th September 1912 the Young Citizen Volunteers

Young Citizen Volunteers 10th September 1912 The Young Citizen Volunteers Introduction Lance-Corporal Walter Ferguson , aged 24, of 14th Royal Irish Rifles died (according to the website of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission) on 8 July 1916, although the marble tablet erected in All Saints Parish Church, University Street, Belfast, by his sorrowing father states he was ‘killed in action on 1 July 1916’. It seems very probable that he died a slow and possibly painful death from wounds sustained on 1 July and in captivity because he is buried in Caudry Old Communal Cemetery which was then in German-held territory. Walter’s family did not learn of his death immediately. They sought news of him in the Belfast Evening Telegraph of 18 July 1916: No news has been received regarding L’ce Corporal Walter Ferguson (14596) YCVs since before the Big Push and his relatives, who reside at 2 Collingwood Road, Belfast, are very anxious about him and would be grateful for any information. In civil life he was a bookbinder … News from the Front often trickled home agonizingly slowly. For example, the Northern Whig of 27 July 1916 reveals another Belfast family anxious to learn the fate of their son, also a lance-corporal in 14th Royal Irish Rifles and a member of the YCV: Revd John Pollock (St Enoch’s Church), 7 Glandore Park, Antrim Road, will be glad to receive any information regarding his son Lance-corporal Paul G Pollock, scout, Royal Irish Rifles (YCV), B Company, who had engaged in the advance of the Ulster Division on 1st July last, and has been ‘missing’ since that date. -

Statute Law Revision Act 2012 ———————— Arran

Click here for Explanatory Memorandum ———————— Number 19 of 2012 ———————— STATUTE LAW REVISION ACT 2012 ———————— ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS Section 1. Definitions. 2. General statute law revision repeal and saver. 3. Specific repeals. 4. Assignment of short titles. 5. Miscellaneous amendments to short titles. 6. Savings. 7. Amendment of Adaptation of Enactments Act 1922. 8. Short title and collective citations. SCHEDULE 1 ACTS SPECIFICALLY RETAINED PART 1 Irish Private Acts 1751 to 1800 PART 2 Private Acts of Great Britain 1751 to 1800 PART 3 United Kingdom Private Acts 1801 to 1922 PART 4 United Kingdom Local and Personal Acts 1851 to 1922 1 [No. 19.]Statute Law Revision Act 2012. [2012.] SCHEDULE 2 ACTS SPECIFICALLY REPEALED PART 1 Irish Private Acts 1751 to 1800 PART 2 Private Acts of Great Britain 1751 to 1800 PART 3 United Kingdom Private Acts 1801 to 1922 PART 4 United Kingdom Local and Personal Acts 1851 to 1922 ———————— Acts Referred to Adaptation of Charters Act 1926 1926, No. 6 Adaptation of Enactments Act 1931 1931, No. 34 Adaptation of Enactments Act 1922 1922, No. 2 Constitution (Consequential Provisions) Act 1937 1937, No. 40 Drainage and Improvement of Lands Supplemental Act (Ireland) 1868 31 & 32 Vict., c. clvii Drainage and Improvement of Lands Supplemental Act (Ireland) 1868 31 & 32 Vict., c. clviii Drainage and Improvement of Lands Supplemental Act (Ireland) 1873 36 & 37 Vict., c. xv Interpretation Act 2005 2005, No. 23 Local Government Act 2001 2001, No. 37 Lough Swilly and Lough Foyle Reclamation Acts Amend- ment 1853 16 & 17 Vict., c. lxv Short Titles Acts 1896 to 2009 Statute Law Revision Act 2007 2007, No. -

Town Records

CARRICKFERGUS TOWN RECORDS Short Calendar for Researchers A Note to the Reader The following is a descriptive listing of the contents of the volumes held by Carrickfergus Museum pertaining to the town’s records from the eighteenth century on. It is anticipated that it be used as a starting point for researchers wishing to investigate the town’s municipal past; however, it is not suitable as a wholesale replacement for consulting the documents themselves. It is not entirely clear what happened to the earlier material; clearly it existed in some form as Richard (Dean) Dobbs made a copy in 1785, but by 1786 the committee set up for the purpose of compiling an updated catalogue complained they had to rely on the catalogue of 1738, as a number of original documents were ‘lost or mislaid’. (TR/03). However, there does not seem to be much overlap between the reported missing documents (leases etc) and the contents of Dean Dobbs’ Records of Carrickfergus, as copied from the old books of records which is altogether more colourful and can be consulted in typescript at Carrickfergus Library. The concern for the town’s records seen in the 1780s marks a gradual shift towards a professional approach to those same records and indeed to the work of administering the borough as a whole. This trend accelerates throughout the nineteenth century and is demonstrated within the records by references to staff salaries, finances, uniforms, the regularisation of meeting times and locations, and increased concern with the security of items relating to the town’s administration, including valuable objects such as the mace and sword. -

Church History

St Mary Magdalene Parish Church Donegall Pass, Belfast (Grade ‘B’ listed building) Church of Ireland Diocese of Connor A history 1839-2010 The following article describing a visit to St Mary Magdalene Church, appeared in ‘Nomad’s Weekly ’ - 5th May 1906: “St Mary Magdalene —What a beautiful name for a church! There is something particularly sympathetic in the very sound of the title, which, if one could rid themselves of the significant associations which cling to the word ‘Magdalene’, would suggest wonderful possibilities. ……..” As you stroll through the history pages of our beloved church, may you come to experience those possibilities. May you walk with all the parishioners, who have lived and worshipped here over time. Contents List of photographs ......................................................................................... 2 Background ........................................................................................................ 3 The Magdalene Asylum and Episcopal Chapel ........................................... 4 The fire and rebuild ........................................................................................ 8 Closure of the Asylum .................................................................................. 14 Magdalene Schoolhouse and Parochial Hall(s) ........................................ 16 Charlotte Street Hall ................................................................................... 18 Magdalene National School ........................................................................ -

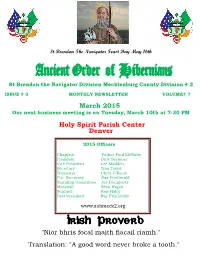

Ancient Order of Hibernians

St Brendan The Navigator Feast Day May 16th Ancient Order of Hibernians St Brendan the Navigator Division Mecklenburg County Division # 2 ISSUE # 3 MONTHLY NEWSLETTER VOLUME# 7 March 2015 Our next business meeting is on Tuesday, March 10th at 7:30 PM Holy Spirit Parish Center Denver 2015 Officers Chaplain Father Paul McNulty President Dick Seymour Vice President Lee Madden Secretary Tom Dowd Treasurer Chris O’Keefe Fin. Secretary Ray FitzGerald Standing Committee Joe Dougherty Marshall Sean Ragan Sentinel Ron Haley Past President Ray FitzGereld www.aohmeck2.org "Níor bhris focal maith fiacail riamh." Translation: "A good word never broke a tooth." President’s Message St. Brendan the Navigator Pray for Us St. Patrick Pray for Us Erin go Baugh Brothers, Here we are, the month of St. Patrick, a busy month for our Division. It’s time to proudly display our heritage. If you haven’t been able to participate in or volunteer to help at our events or activities in the past, this is the perfect time to make that extra effort. Keep alert to our e-mails, website and information in this Newsletter to see how you can help. As we approach St. Patrick’s Day, be alert to stores, kiosks, vendors promoting or selling merchandise that defames or disparages the Irish heritage. Typical are t-shirts depicting the Irish as drunkards and the like. Don’t hesitate to complain either in person or in writing to the vendor or the establishment’s management that you find this offensive and politely ask them to discontinue displaying or selling the items. -

THE LONDON GAZETTE, OCTOBER 14, 1862. Commissions Signed by the Lord Lieutenant of the [Extract from the Dublin Gazette of 10Th October, County of Dorset

4888 THE LONDON GAZETTE, OCTOBER 14, 1862. Commissions signed by the Lord Lieutenant of the [Extract from the Dublin Gazette of 10th October, County of Dorset. 1862.] 1st Administrative Battalion of Dorsetshire Rifle Crown and Hanaper Office, Volunteers. 10th October, 1362. Henry Augustus Templer, Esq., to be Major. ELECTION OF A TEMPORAL PEER OF Dated 7th October, 1862. IRELAND. 1st Dorsetshire Rifle Volunteers. IN pursuance of an Act, passed ,in the fortieth year of the reign of His Majesty King George Captain Henry Saunders Edwards to be Captain- the Third, entitled " An Act to regulate the mode Commandant. Dated 7th October, .1862. " by which the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and " the Commons, to serve in the Parliament of the Commissions signed by the Vice-Lieutenant of the " United Kingdom, on the part of Ireland, shall be East Riding of the County of York, and the " summoned and returned to the said Parliament," Borough of Kingston-upon-Hull. I do hereby give notice, that Writs bearing teste East York Artillery Volunteers. this day, have issued for electing a Temporal Peer of Ireland, to succeed to the vacancy made by 4th Corps (Hull). the demise of Arthur, "Viscount Ducgannon, in Joseph Hickson Peart, Esq., to be' Second Lieu- the House of Lords, of the said United Kingdom, tenant, vice Heaven, promoted. Dated 2nd which said Writs are severally directed to the fol- September, 1862. lowing Peers who sat and voted in the House of Charles Henry Garthorne, Esq., to be Second Lords in Ireland before the Union, or whose right Lieutenant. Dated 2nd September, 1862. -

Survey Report: No. 1 Survey of Limekiln at Dunanney, Carnmoney County Antrim

Survey Report: No. 1 Survey of Limekiln at Dunanney, Carnmoney County Antrim. Lizzy Pinkerton First published March 2014 © Belfast Hills Partnership Belfast Hills Partnership 9 Social Economy Village Hannahstown Hill Belfast BT17 0XS www.belfasthills.org Tel: 028 9060 3466 E-mail: [email protected] Cover illustration: Front of limekiln, looking west Fig 1 i CONTENTS Page List of figures ii 1. Summary 1 2. Credits and acknowledgements 1 3. Introduction 1 4. Limekiln survey 5 5. Discussion 8 6. Conclusions and Recommendations for further work 15 7. Bibliography 15 Appendix A. Photographic record form 16 B. Geology of Carnmoney Hill 18 C. Townland name 19 ii LIST OF FIGURES Figures Page 1 Front of Limekiln, looking west Cover 2 Location of Lime Kiln- Google MapsTM(satellite view) 2 3 Location of Lime Kiln- Google Maps (map view) 2 4 Limekilns, Dunanney TD, Co. Antrim, OS 1st Edition map 4 6” County Series (part of) OS-6-1-57-1(1833) 5 Griffith Valuation Map (extract) – Dunanney, 1861 (askaboutireland.ie) 4 6 Latest map - Dunanney TD - OSNI, Historical Map Store 5 7 Survey Team members in action at Dunanney, 17th August 2013 6 8 Survey Site Plan, east facing elevation 6 9 Overview sketch plan 7 10 Illustration of a Limekiln in operation and link to film of limekiln 10 working 11 View of limekiln during survey, looking west 11 12 Griffith valuation extract, 1861 12 13 Griffith valuation, original table, 1861 12 14 View of upper laneway towards farmhouse, looking north-west 13 15 View of top of limekiln in foreground with access laneway, looking west 13 16 Detail of northern recess in arch, looking north 14 17 Detail of southern recess in arch, looking south 14 18 View of limekiln before commencing survey, looking west 17 19 View of limekiln arch, looking west 17 20 Detail of draw-hole, looking west 17 21 Socket from which stone fallen out in arch 17 22 Possible quarry sites around Carnmoney Hill marked in blue on Griffiths 18 valuation map 1 1. -

Belfast Northern Ireland

BELFAST NORTHERN IRELAND elfast, the capital of BNorthern Ireland lies on Belfast Lough, at the mouth of the River Lagan on Northern Ireland’s east coast. With a popu- lation of nearly half a million people, Belfast is Northern Ireland’s largest city. The port of Belfast is Northern Ireland’s principle maritime gateway. It is also home to the world’s largest dry dock and the Harland and Wolff shipyard, famous for build- ing the Titanic. Northern Ireland, with an area of 5463 square miles, is also known as Ulster because it compris- es six of the nine counties that used to constitute the former province of Ulster. Northern Ireland enjoyed a reputation for science, innovation and was a leading force in the Industrial Revolution. Industries like rope-making, linens and shipbuild- ing created an economic powerhouse. Wealth from HISTORY the period is reflected in First inhabitants of the Belfast area can be dated back as early as the stately Edwardian and Bronze Age. During the Iron Age, the Celtic culture flourished and the Victorian architecture distinctive language and culture was spread throughout the region. The found throughout Belfast. name Belfast comes from the Irish Béal Feirste, or mouth of the Farset, The city is once again the river on which the city was established. a driving force into the future. The economy is Christianity arrived in Ireland during the 4th century with Saint Patrick. Ire- thriving and Belfast is re- land endured Viking raids in the 9th century followed by Norman conquest inventing itself. in the 12th. English and Scottish settlers began arriving in Belfast early in the 17th century. -

On Broadway Daniel Jewesbury & Robert Porter

On Broadway Daniel Jewesbury & Robert Porter We will never find the sense of something…if we do not know the force which appropriates the thing, which exploits it, which takes possession of it or is expressed in it…The history of a thing…is the succession of forces which take possession of it and the co-existence of the forces which struggle for possession. The same object… changes sense depending on the force which appropriates it…Sense is therefore a complex notion; there is always a plurality of senses, a constellation, a complex of successions but also of coexistences which make interpretation an art. Gilles Deleuze (1986) Nietzsche and Philosophy (London: Athlone), pp. 3-4. 1 How can we make sense of a space like Broadway roundabout in Belfast? What could it mean to interpret what is going on in this space? It is important to understand that Broadway is an object, a thing, a constellation and succession of forces, forces which appropriate it, shape it, bend it and reshape it; that is, so many interpretations that force it this way and that... So the question of what it means to read a space, interpret it, negotiate it, can only be posed through its interpretation, through its negotiation, literally through a movement in the space, and through its forceful appropriation as this or that, this and then that... In this way, the interpretation and negotiation of the space not only seeks to trace the forces at play in it, it itself is a series of forces as such; that is, it forcefully plays through the space, bending, reshaping, appropriating it as it goes. -

Ellis Wasson the British and Irish Ruling Class 1660-1945 Volume 2

Ellis Wasson The British and Irish Ruling Class 1660-1945 Volume 2 Ellis Wasson The British and Irish Ruling Class 1660-1945 Volume 2 Managing Editor: Katarzyna Michalak Associate Editor: Łukasz Połczyński ISBN 978-3-11-056238-5 e-ISBN 978-3-11-056239-2 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. © 2017 Ellis Wasson Published by De Gruyter Open Ltd, Warsaw/Berlin Part of Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published with open access at www.degruyter.com. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Managing Editor: Katarzyna Michalak Associate Editor: Łukasz Połczyński www.degruyteropen.com Cover illustration: © Thinkstock/bwzenith Contents The Entries VII Abbreviations IX List of Parliamentary Families 1 Bibliography 619 Appendices Appendix I. Families not Included in the Main List 627 Appendix II. List of Parliamentary Families Organized by Country 648 Indexes Index I. Index of Titles and Family Names 711 Index II. Seats of Parliamentary Families Organized by Country 769 Index III. Seats of Parliamentary Families Organized by County 839 The Entries “ORIGINS”: Where reliable information is available about the first entry of the family into the gentry, the date of the purchase of land or holding of office is provided. When possible, the source of the wealth that enabled the family’s election to Parliament for the first time is identified. Inheritance of property that supported participation in Parliament is delineated. -

Vigorous and Whole: Canadian Brides of British Peers and Their

3carter.ac 2014-08-27 4:25 PM Page 334 Vigorous and Wholesome CanadianCanadian BridesBrides ofof BritishBritish PeersPeers and Their American Rivals 3carter.ac 2014-08-27 4:25 PM Page 335 SARAH CARTER Titled colonial women, including many Canadians, were vastly superior to their American “rivals,” according to London columnist Jessie Weston. She dismissed Anglo- American marriages as alliances between titles and dollars, and claimed that American wives were shallow, vulgar, frivolous, and extravagant. They invaded the British Isles, where they deliberately “shopped” for husbands. With a clear anti-Semitic message mingled with eugenics, titled American women were condemned for being of “foreign parentage or descent.” They were either “sterile” or had very few children and were not good at producing sons. By contrast, titled colonial women, according to Weston, were “nearly all English,” were brought up with a passionate loyalty for the Mother Country, and had many sons … VQ YRRZ \X ^RQ PNWNQUNW ORN]\_” was one of the headlines “Odescribing the December EMDF wedding that caused a sensation throughout the British Empire and in the United States, even though mar- riages between impoverished British peers and American heiresses were reasonably common. The marriage of FF-year-old Violet Twining, from Halifax, Nova Scotia, and the titled but penniless octogenarian George Augustus Chichester, the Marquess of Donegall, was astounding. The groom was denounced in the press as a “notorious rogue,” a “hopeless bankrupt,” and a “senile old wreck.” Twining had allegedly answered an advertisement placed in the London papers by the marquess, offering his hand in marriage and his title in return for an annuity. -

Ellis Wasson the British and Irish Ruling Class 1660-1945 Volume 2

Ellis Wasson The British and Irish Ruling Class 1660-1945 Volume 2 Ellis Wasson The British and Irish Ruling Class 1660-1945 Volume 2 Managing Editor: Katarzyna Michalak Associate Editor: Łukasz Połczyński ISBN 978-3-11-056238-5 e-ISBN 978-3-11-056239-2 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. © 2017 Ellis Wasson Published by De Gruyter Open Ltd, Warsaw/Berlin Part of Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published with open access at www.degruyter.com. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Managing Editor: Katarzyna Michalak Associate Editor: Łukasz Połczyński www.degruyteropen.com Cover illustration: © Thinkstock/bwzenith Contents The Entries VII Abbreviations IX List of Parliamentary Families 1 Bibliography 619 Appendices Appendix I. Families not Included in the Main List 627 Appendix II. List of Parliamentary Families Organized by Country 648 Indexes Index I. Index of Titles and Family Names 711 Index II. Seats of Parliamentary Families Organized by Country 769 Index III. Seats of Parliamentary Families Organized by County 839 The Entries “ORIGINS”: Where reliable information is available about the first entry of the family into the gentry, the date of the purchase of land or holding of office is provided. When possible, the source of the wealth that enabled the family’s election to Parliament for the first time is identified. Inheritance of property that supported participation in Parliament is delineated.