Imagereal Capture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Plan

APPENDIX 12 ATTACHMENT 1 Cultural Plan 2021 - 2025 This plan is available upon request in alternative languages and formats upon request. joondalup.wa.gov.au ii City of Joondalup – Cultural Plan 2021 City of Joondalup – Cultural Plan 2021 iii Contents Executive Summary ............ iv Context .............................. 4 Culture in the City of Joondalup .............. 8 Developing the Plan ............ 14 The Plan ............................ 17 Reviewing the Plan and Monitoring Progress ........... 23 The City acknowledges the custodians of this land, the Whadjuk Noongar and their Elders past, present and emerging. The City acknowledges and respects their continuing culture and the contribution they make to the life of this city and this region. iv City of Joondalup – Cultural Plan 2021 Executive Summary Since its early days, the City has developed a The resulting Cultural Plan has been developed to reputation for managing high quality cultural respond to these community sentiments, increasing destinations, assets and events, many of which access to the arts, and embedding cultural moments appeal to visitors from the wider Perth metropolitan in everyday life. The Plan provides strategic direction area. In doing so the City has successfully for the City of Joondalup’s activities for the period of demonstrated how culture plays a significant 2021 - 2025, ensuring investment is directed towards role in visitor and resident attraction, community the programming and infrastructure most valued cohesiveness and quality of life. by the community. This includes strategic initiatives which grow the City’s cultural capacity and audience, From its inception as a newly formed local in consideration of future plans for signficant cultural government in the late 1990s, the City of Joondalup infrastructure including the proposed Joondalup has successfully implemented cultural events such as Performing Arts Facility. -

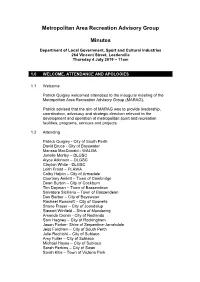

Metropolitan Area Recreation Advisory Group Minutes

Metropolitan Area Recreation Advisory Group Minutes Department of Local Government, Sport and Cultural Industries 264 Vincent Street, Leederville Thursday 4 July 2019 – 11am 1.0 WELCOME, ATTENDANCE AND APOLOGIES 1.1 Welcome Patrick Quigley welcomed attendees to the inaugural meeting of the Metropolitan Area Recreation Advisory Group (MARAG). Patrick advised that the aim of MARAG was to provide leadership, coordination, advocacy and strategic direction relevant to the development and operation of metropolitan sport and recreation facilities, programs, services and projects. 1.2 Attending Patrick Quigley - City of South Perth David Bruce - City of Bayswater Marissa MacDonald - WALGA Jonelle Morley – DLGSC Alyce Atkinson – DLGSC Clayton White - DLGSC Leith Fradd – PLAWA Colby Halpin – City of Armadale Courtney Amlett – Town of Cambridge Dean Burton – City of Cockburn Tim Dayman – Town of Bassendean Salvatore Siciliano – Town of Bassendean Dan Barber – City of Bayswater Rachael Rowcroft – City of Gosnells Shane Fraser – City of Joondalup Stewart Winfield – Shire of Mundaring Amanda Cronin - City of Nedlands Sam Hegney – City of Rockingham Jason Parker- Shire of Serpentine-Jarrahdale Jess Fordham – City of South Perth Julie Rechichi – City of Subiaco Amy Fuller – City of Subiaco Michael Hayes – City of Subiaco Sarah Perkins – City of Swan Sarah Kitis – Town of Victoria Park Wayne Grimes – City of Vincent Sandra Watson – City of Vincent Samantha Culliver – City of Wanneroo Craig Bartlett – City of Wanneroo Wayne Stuart – City of Wanneroo Dan -

10.1.1 Local Government Reform - Update

COUNCIL MEETING 15 December 2014 10.1.1 LOCAL GOVERNMENT REFORM - UPDATE ATTACHMENTS 1. Letter Local Government Advisory Board 2. Media Statement Funding Package for Reforming Local Government 3. Media Statements Landmark Reports Sets Out New Look for Metro Perth 4. Local Government Advisory Board Notice Right to Request A Poll 5. Information Sheet Proposed City of Riversea Landmark report sets out new look for metro Perth Wednesday, 22 October 2014 Release of the Local Government Advisory Board report on metropolitan local government reform Board recommends Perth’s 30 councils be reduced to 16 Minister accepts all but two of the report’s boundary recommendations in the biggest shake-up of local government in 100 years Government to introduce City of Perth Act to reflect capital’s status New local governments will have increased financial sustainability and capacity to cope with Perth’s population growth The State Government today released the Local Government Advisory Board report, which provides the framework for the most significant reform of metropolitan local government in 100 years. Of the report's boundary recommendations for metropolitan Perth, Local Government Minister Tony Simpson has accepted all but two, those for the City of Perth/City of Vincent and the proposed City of Riversea, which includes five western suburbs councils. The Minister has rejected the Board’s recommendation for the City of Perth, on the basis that key icons such as The University of Western Australia (UWA) and the Queen Elizabeth II Medical Centre (QEII), were not included. As a result of the flow-on effects from City of Perth changes, he has also rejected the recommendation for the proposed City of Riversea, which includes five western suburbs councils. -

City of Melville Health and Wellbeing Profile 2019

City of Melville Health and Wellbeing Profile 2019 South Metropolitan Health Service Health Promotion Page 1 of 23 Acknowledgment The South Metropolitan Health Service (SMHS) respectfully acknowledges the Aboriginal Noongar people both past and present, the traditional owners of the land on which we work. Notes In this report: The terms ‘City of Melville’ and ‘Melville LGA’ are used interchangeably. The use of the term ‘Aboriginal’ within this document refers to Australians of both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Important disclaimer All information and content in this material is provided in good faith by the WA Department of Health, and is based on sources believed to be reliable and accurate at the time of development. The State of Western Australia, the WA Department of Health and their respective officers, employees and agents, do not accept legal liability or responsibility for the material, or any consequences arising from its use. Abbreviations ABS Australian Bureau of Statistics AIHW Australian Institute of Health and Welfare BMI Body mass index CI Confidence interval DoH Department of Health, Western Australia ERP Estimated resident population HWSS Health and Wellbeing Surveillance System LGA Local government area NHPA National Health Priority Areas RSE Relative standard error SMHS South Metropolitan Health Service SMHS- HP South Metropolitan Health Service – Health Promotion WA Western Australia City of Melville Health and Wellbeing Profile 2019 Page 2 of 23 Contents Acknowledgment 2 Abbreviations 2 About this -

Local Planning Strategy

Local Planning Strategy nedlands.wa.gov.au www.nedlands.wa.gov.au ADVERTISING The City of Nedlands Local Planning Strategy certified for advertising on / Signed for and on behalf of the Western Australian Planning Commission o v an officer of the Commission duly authorised by the Commission (pursuant to the Planning and Development Act 2005) Date ti tch QO16 ADOPTED The City of Nediands hereby gclopts the Local Planning Strategy, at the meeting of the Council held on the S*i c te entli day of A- tit 3 LA St 201%, d).'..40 CA MAYOR/SHIRE PRESItJENT CHEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER ENDORSEMENT Endorsed by the Western Australian Planning Commission on an officer of the Commission duly authorised by the Commission (pursuant to the Planning and Development Act 2005) Date 02G / 0/ 7 DISCLAIMER This document has been published by the City of Nedlands. Any representation, statement, opinion or advice expressed or implied in this publication is made in good faith and on the basis that the City, its employees and agents are not liable for any damage or loss whatsoever which may occur as a result of action taken or not taken, as the case may be, in respect of any representation, statement, opinion or advice referred to herein. While the City has tried to ensure the accuracy of the information in this publication, the Publisher accepts no responsibility or liability for any errors, omissions or resultant consequences including any loss or damage arising from reliance in information in this publication. Professional advice should be obtained before applying the information contained in this document to particular circumstances. -

Shenton Park Rehabilitation Hospital

DilFHOVEfilEMT FLAM MOn 43 SHEWTON PARK REHABILITATION HOSPITAL Western ^;y\ Australian ^M/f Planning ; ™ Commission WESTERN AUSTRALIAN PLANNING COMMISSION APRIL 2016 Page 1 of 6 IMPROVEMENT PLAN NO. 43 SHENTON PARK REHABILITATION HOSPITAL Introduction 1. Under Section 119 of the Planning and Development Act 2005, the Western Australian Planning Commission (WAPC) is authorised to certify and recommend to the Minister for Planning that an Improvement Plan should be prepared for the purpose of advancing the planning, development and use of any land within the State of Western Australia. 2. The Improvement Plan provisions of the Planning and Development Act 2005 provides for the WAPC, with the approval of the Governor, to; D Plan, replan, design, redesign, consolidate, re-subdivide, clear, develop, reconstruct or rehabilitate land held by it under the Act or enter into agreement with any owner of land not held by it within the Improvement Plan area. ¦ Provide for the land to be used for such purposes as may be appropriate or necessary. H Make necessary changes to land acquired or held by it under the Act. B Manage the tenure or ownership of the land or any improvements to that land held by it under the Act or enter into agreement with other owners of land within the Improvement Plan area for the same purpose. ¦ Enter into agreement for the purpose, surrender, exchange, vesting, allocation or other disposal of land, including the adjustment of boundaries. H Recover costs in implementing the agreement with any owner of land within the Improvement Plan area. b Do any act, matter or thing for the purpose of carrying out any agreement entered into with other land owners. -

CITY of MELVILLE Ephemera PR14522/MEL L CALL NO

CITY OF MELVILLE Ephemera PR14522/MELL To view items in the Ephemera collection, contact the State Library of Western Australia CALL NO. DESCRIPTION PR14522/MEL/1 Melville public libraries. Hours of opening. Pamphlet. 15 February 1968 PR14522/MEL/2 Official celebration dinner. Toast list and banquet menu and quotations. 2 May 1968 PR14522/MEL/3 A portrait of your city. Pamphlet. August 1974 PR14522/MEL/4 Canning Bridge Public Library. An introduction to the library service. Pamphlet. 1974 PR14522/MEL/5 Invitation to meet WA author Gerald Glaskin. 9 June 1976 PR14522/MEL/6 Melville public libraries. Writer's evening. WA author Gerald Glaskin. Pamphlet. 1977 PR14522/MEL/7 Town of Melville public libraries readers ticket & bookcard. 1977 PR14522/MEL/8 Melville public libraries. Members card. 1977 PR14522/MEL/9 Melville public libraries. New books request slip. 1968 PR14522/MEL/10 Melville public libraries. Date return card. 1968 PR14522/MEL/11 The occasion to mark the Grant of Armorial Bearings to the Municipality of City of Melville. 26 July 1981 D PR14522/MEL/12 Wireless Hill Park and Telecommunications Museum. Pamphlet. October 1981 PR14522/MEL/13 Wireless Hill Park and Telecommunications Museum. Pamphlet. February 1984 PR14522/MEL/14 Social Welfare Service. Pamphlet. 1985 PR14522/MEL/15 Southern Districts Community Recreation Centre. Second term programme. 4 May 1987 PR14522/MEL/16 Residents' and Ratepayers' Association Inc. Sub‐Committee to amend Melville Town Planning Scheme No 3. 4 December 1985 PR14522/MEL/17 Residents' and Ratepayers' Association Inc. Re Melville Town Planning Scheme No 3. 3 December 1985 PR14522/MEL/18 What is happening to Alfred Cove. -

City of Subiaco Community Directory

City of Subiaco Community Directory August 2020 1 The City of Subiaco Community Directory The City of Subiaco is committed to supporting the community by providing relevant information in an accessible, easy to read format. The Community Directory contains information about Federal and State government departments, health and wellbeing associations, local community groups and local support organisations that are available to our community members. This directory will be reviewed and updated periodically to ensure the information remains relevant and accurate. If you are a service provider and would like your service to be listed in this directory, please contact the City of Subiaco on 9237 9222 or email [email protected] to find out more. The Community Directory is available to download from the City’s website. Hard copies of the directory can also be requested and posted to community members living in the City of Subiaco. If you would like a hard copy of the directory posted to you, please contact the City of Subiaco on 9237 9222 or email [email protected]. For more information about other City initiatives that support the community and business visit our website at www.subiaco.wa.gov.au or keep an eye out for the next issue of the Talk About Subi newsletter. 2 Contents Emergency Services ............................................................................................................................ 7 Police ............................................................................................................................................. -

Agenda Paper

CITY OF COCKBURN ORDINARY COUNCIL AGENDA PAPER FOR TUESDAY 18 JULY 2000 1 CITY OF COCKBURN SUMMARY OF AGENDA TO BE PRESENTED TO THE ORDINARY COUNCIL MEETING TO BE HELD ON TUESDAY, 18 JULY 2000 AT 7:30 P.M. Page 1. DECLARATION OF OPENING ..................................................................... 1 2. APPOINTMENT OF PRESIDING MEMBER (IF REQUIRED) ...................... 1 3. DISCLAIMER (To be read aloud by Presiding Member) .............................. 1 4. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF RECEIPT OF WRITTEN DECLARATIONS OF FINANCIAL INTERESTS (by Presiding Member) ................................... 1 5. APOLOGIES AND LEAVE OF ABSENCE ................................................... 1 6. ACTION TAKEN ON PREVIOUS PUBLIC QUESTIONS TAKEN ON NOTICE ........................................................................................................ 1 7. PUBLIC QUESTION TIME ........................................................................... 2 8. CONFIRMATION OF MINUTES ................................................................... 2 8.1 (ocm1_7_2000) - ORDINARY COUNCIL MEETING - 20/6/2000 2 9. WRITTEN REQUESTS FOR LEAVE OF ABSENCE ................................... 2 10. DEPUTATIONS AND PETITIONS ................................................................ 2 11. BUSINESS LEFT OVER FROM THE PREVIOUS MEETING (If adjourned) .................................................................................................... 3 12. COUNCIL MATTERS .................................................................................. -

Recreational Waters Bacterial Quality Monitoring Program Swan and Canning Rivers - Global Positioning System - Reference Points

Recreational Waters Bacterial Quality Monitoring Program Swan and Canning Rivers - Global Positioning System - Reference Points GPS Deci GPS Deci Water Site Code Site Name LGA District Managing Authority Degs_S Degs_E body EV3/522 Sandy Beach Reserve -31.92215 115.95087 BASSENDEAN Town of Bassendean River EV3/548 Point Reserve (Nth Jetty) -31.9041 115.962726 BASSENDEAN Town of Bassendean River EV3/523 Hind Reserve (Garratt Rd - Jetty) -31.93125 115.91724 BAYSWATER City of Bayswater River EV3/541 East St Maylands Yacht Club -31.93723 115.89096 BAYSWATER City of Bayswater River EV3/517 Garvey Park (Fauntleroy Ave) -31.92121 115.94295 BELMONT City of Belmont River Belmont Park Beach (End Beach - EV3/538 -31.95349 115.89873 BELMONT City of Belmont River Goodwood Pd) EV3/539 Cracknell Park (Riversdale Rd) -31.95391 115.90326 BELMONT City of Belmont River EV3/542 Shelly Beach (Near Drain) -32.02762 115.88249 CANNING City of Canning River EV3/547 Clontarf Bay (Cadets) -32.02088 115.89865 CANNING City of Canning River EV3/545 Preston Point - John Tonkin Park -32.02903 115.76196 EAST FREMANTLE Town of East Fremantle River EV3/505 Bicton Baths -32.0276 115.77819 MELVILLE City of Melville River EV3/507 Cunningham St (Applecross) -32.02252 115.82608 MELVILLE City of Melville River EV3/532 Point Walter (Kiosk) -32.01294 115.79115 MELVILLE City of Melville River EV3/533 Point Walter (Boat Ramps) -32.0121 115.78834 MELVILLE City of Melville River EV3/534 Waylen Bay (Scout Hall) -32.00445 115.84057 MELVILLE City of Melville River EV3/540 Deep Water Point -

Agenda ORDINARY COUNCIL MEETING (OC 04/20)

Agenda ORDINARY COUNCIL MEETING (OC 04/20) 6 August 2020 Commencing at 5:30 pm Town of Claremont 308 Stirling Hwy Claremont WA 6010 Suite 2/ 317 Churchill Avenue, Subiaco WA 6008 T 08 9384 4003 | E [email protected] | www.wmrc.wa.gov.au Dear Chairman and Councillors I advise that an Ordinary Meeting of the Western Metropolitan Regional Council will be held at the Town of Claremont, 308 Stirling Hwy, Claremont, WA 6010 on 6 August 2020 commencing at 5.30pm. Stefan Frodsham Chief Executive Officer 27 May 2020 Note for members of the public: Council Meetings – Procedures 1. All Council meetings are open to the public, except for matters raised by Council under “confidential items”. 2. Members of the public may ask a question at an Ordinary Council Meeting under “public question time” or prior to the meeting online through this link. 3. Members of the public who are unfamiliar with meeting procedures are invited to seek advice at the meeting. 4. All other arrangements are in accordance with the Council’s Meeting Procedures Local Law, policies and decisions of the organisation. Stefan Frodsham Chief Executive Officer WMRC Member Councils Town of Claremont | Town of Cottesloe | Town of Mosman Park | City of Subiaco | Shire of Peppermint Grove Agenda 6 August 2020 2 CONTENTS DECLARATION OF OPENING ................................................................................................ 4 RECORD OF ATTENDANCE AND APOLOGIES..................................................................... 4 DISCLOSURES OF INTERESTS ............................................................................................ -

WESROC Regional Strategy for Management Of

Western Suburbs Regional Organisation of Councils Regional Strategy for Management of Stormwater Quality Volume 2 – Figures JDA Consultant Hydrologists May 2002 Western Suburbs Regional Organisation of Councils Regional Strategy for Management of Stormwater Quality CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES 1. LOCATION MAP / STUDY AREA 2. TOPOGRAPHY 3. ANNUAL AND MONTHLY RAINFALL 4. ENVIRONMENTAL GEOLOGY MAP 5. MAXIMUM RECORDED GROUNDWATER LEVEL CONTOURS (VIA WRC GROUNDWATER ATLAS) 6. CONSERVATION CATEGORY WETLANDS AND BUSH FOREVER SITES 7. WRC MONITORING SITES 8. PRIMARY AND SECONDARY ROAD NETWORK 9. TOWN OF CLAREMONT LAND USE 10. TOWN OF CLAREMONT SUB CATCHMENTS 11. TOWN OF CAMBRIDGE LAND USE 12. TOWN OF CAMBRIDGE SUB CATCHMENTS 13. TOWN OF COTTESLOE LAND USE 14. TOWN OF COTTESLOE SUB CATCHMENTS 15. TOWN OF MOSMAN PARK LAND USE 16. TOWN OF MOSMAN PARK SUB CATCHMENTS 17. CITY OF SUBIACO LAND USE 18. CITY OF SUBIACO SUB CATCHMENTS 19. CITY OF NEDLANDS LAND USE 20. CITY OF NEDLANDS SUB CATCHMENTS 21. SHIRE OF PEPPERMINT GROVE LAND USE 22. SHIRE OF PEPPERMINT GROVE SUB CATCHMENTS 23. WESROC DRAINAGE OVERVIEW 24. NUTRIENT INPUT BY TOTAL PHOSPHORUS 25. MAJOR ROADS BY DENSITY 26. COMMERCIAL/INDUSTRIAL AREAS BY PERCENTAGE 27. LOCAL AUTHORITY PRIORITY SUB CATCHMENTS 28. REGIONAL PRIORITY SUB CATCHMENTS 29. NIDSS MODELLING RESULTS FOR PHOSPHORUS INPUT REDUCTION 30. IMPACT OF EDUCATION CAMPAIGNS ON PHOSPHORUS INPUT REDUCTION May 2002 1 x i rerdsmn vke vke wonger ploret2feh own2of2gmridge gity2feh erry vkes sndin2 gity2of2uio yen uings2rk gity2of2xedlnds vke glremont