Eisodos2017.2.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peter Constantine

Peter Constantine ————————————————————————————- Literary Translation Program Department of Literatures, Cultures, and Languages University of Connecticut Storrs, CT 06269-1057 ACADEMIC POSITIONS • Director, Literary Translation Program, Department of Literatures, Cultures, and Lan- guages, University of Connecticut. 2016 — Present. • Humanities Institute, University of Connecticut. Fellow. 2015 — 2016. • Columbia University, Program in Hellenic Studies. Fellow. 2007 – 2015. • Princeton University, Program in Hellenic Studies. Translation Workshop in Paros, Greece. Instructor. 2009, 2011. • Banff International Literary Translation Centre. Instructor, Consulting Specialist, 2011. • Princeton University, Program in Hellenic Studies. Writer-in-Residence, 2002 - 2003. • Princeton University, Program in Hellenic Studies. Stanley J. Seeger Fellow, 2002. AWARDS • Honorary Doctorate of Humane Letters, University of Connecticut, 2016. • PEN Translation Prize (citation), 2008, for The Essential Writings of Machiavelli. • Helen and Kurt Wolff Translation Prize, 2007, for The Bird is a Raven by Benjamin Lebert. • National Jewish Book Award, 2002, (citation) for The Complete Works of Isaac Babel. • The Koret Jewish Literature Award, 2002, for The Complete Works of Isaac Babel. • Hellenic Association of Translators of Greek Literature Prize. 2001. • National Translation Award, 1999, for The Undiscovered Chekhov: Thirty-eight New Sto- ries. • PEN Translation Prize, 1998, for Thomas Mann—Six Early Stories. FELLOWSHIPS • Institute for the Liberal Arts, Boston College, Residency, October 2014. • Fellowship of the Austrian Literature Society, Vienna, 2013. • Ellen Maria Gorrissen Berlin Prize Fellow at the American Academy in Berlin, 2012. • Guggenheim Fellowship, 2011. • Cullman Center Fellowship, New York Public Library, 2011. !2 • National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellowship for Translation, 2011. • Literary Colloquium Berlin. 2008. • National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellowship for Translation, 2004. -

The Idea of 'Celtic Justice' in the Greco-Roman Lighter Literature

Cruel and Unusual? The Idea of ‘Celtic justice’ in the Greco-Roman Lighter Literature Antti Lampinen Abstract This article seeks to demonstrate that dramatically illustrated examples of the Celts’ sense of justice emerge as a minor trope in Greek and Roman ‘lighter literature’. In sources ranging from the Hellenistic to the Imperial era, novelistic narratives taking their cue from the register of lighter literature—with its emphasis on pathos, cultural difference, and romantic themes—feature several barbarian characters, characterised as ‘Celts’ or ‘Galatae’, who act according to a code of conduct that was constructed purposefully as barbarian, archaic, and alien. This set of motifs I venture to call the trope of ‘Celtic justice’. While almost certainly devoid of historical source value to actual judicial cultures of Iron Age Europeans, neither are these references mere alterité. Instead, their relationship with other literary registers demonstrate the literariness of certain modes of thought that came to inform the enquiry of Greek and Roman observers into the Celtic northerners. Their ostensibly ethnographical contents emerge as markers of complex textual strategies and vibrant reception of literary motifs. While lacking ‘anthropological’ source value, these texts demonstrate the variety and intensity with which the contacts between Greeks and Celts affected the epistemic regime of the Mediterranean societies.* From the 270s onwards the Hellenistic era witnessed among the Greeks an intense and emotionally charged interest in Celts. -

Select Epigrams from the Greek Anthology

SELECT EPIGRAMS FROM THE GREEK ANTHOLOGY J. W. MACKAIL∗ Fellow of Balliol College, Oxford. PREPARER’S NOTE This book was published in 1890 by Longmans, Green, and Co., London; and New York: 15 East 16th Street. The epigrams in the book are given both in Greek and in English. This text includes only the English. Where Greek is present in short citations, it has been given here in transliterated form and marked with brackets. A chapter of Notes on the translations has also been omitted. eti pou proima leuxoia Meleager in /Anth. Pal./ iv. 1. Dim now and soil’d, Like the soil’d tissue of white violets Left, freshly gather’d, on their native bank. M. Arnold, /Sohrab and Rustum/. PREFACE The purpose of this book is to present a complete collection, subject to certain definitions and exceptions which will be mentioned later, of all the best extant Greek Epigrams. Although many epigrams not given here have in different ways a special interest of their own, none, it is hoped, have been excluded which are of the first excellence in any style. But, while it would be easy to agree on three-fourths of the matter to be included in such a scope, perhaps hardly any two persons would be in exact accordance with regard to the rest; with many pieces which lie on the border line of excellence, the decision must be made on a balance of very slight considerations, and becomes in the end one rather of personal taste than of any fixed principle. For the Greek Anthology proper, use has chiefly been made of the two ∗PDF created by pdfbooks.co.za 1 great works of Jacobs, -

Dragon Con Progress Report 2021 | Published by Dragon Con All Material, Unless Otherwise Noted, Is © 2021 Dragon Con, Inc

WWW.DRAGONCON.ORG INSIDE SEPT. 2 - 6, 2021 • ATLANTA, GEORGIA • WWW.DRAGONCON.ORG Announcements .......................................................................... 2 Guests ................................................................................... 4 Featured Guests .......................................................................... 4 4 FEATURED GUESTS Places to go, things to do, and Attending Pros ......................................................................... 26 people to see! Vendors ....................................................................................... 28 Special 35th Anniversary Insert .......................................... 31 Fan Tracks .................................................................................. 36 Special Events & Contests ............................................... 46 36 FAN TRACKS Art Show ................................................................................... 46 Choose your own adventure with one (or all) of our fan-run tracks. Blood Drive ................................................................................47 Comic & Pop Artist Alley ....................................................... 47 Friday Night Costume Contest ........................................... 48 Hallway Costume Contest .................................................. 48 Puppet Slam ............................................................................ 48 46 SPECIAL EVENTS Moments you won’t want to miss Masquerade Costume Contest ........................................ -

Queen Arsinoë II, the Maritime Aphrodite and Early Ptolemaic Ruler Cult

ΑΡΣΙΝΟΗ ΕΥΠΛΟΙΑ Queen Arsinoë II, the Maritime Aphrodite and Early Ptolemaic Ruler Cult Carlos Francis Robinson Bachelor of Arts (Hons. 1) A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2019 Historical and Philosophical Inquiry Abstract Queen Arsinoë II, the Maritime Aphrodite and Early Ptolemaic Ruler Cult By the early Hellenistic period a trend was emerging in which royal women were deified as Aphrodite. In a unique innovation, Queen Arsinoë II of Egypt (c. 316 – 270 BC) was deified as the maritime Aphrodite, and was associated with the cult titles Euploia, Akraia, and Galenaië. It was the important study of Robert (1966) which identified that the poets Posidippus and Callimachus were honouring Arsinoë II as the maritime Aphrodite. This thesis examines how this new third-century BC cult of ‘Arsinoë Aphrodite’ adopted aspects of Greek cults of the maritime Aphrodite, creating a new derivative cult. The main historical sources for this cult are the epigrams of Posidippus and Callimachus, including a relatively new epigram (Posidippus AB 39) published in 2001. This thesis demonstrates that the new cult of Arsinoë Aphrodite utilised existing traditions, such as: Aphrodite’s role as patron of fleets, the practice of dedications to Aphrodite by admirals, the use of invocations before sailing, and the practice of marine dedications such as shells. In this way the Ptolemies incorporated existing religious traditions into a new form of ruler cult. This study is the first attempt to trace the direct relationship between Ptolemaic ruler cult and existing traditions of the maritime Aphrodite, and deepens our understanding of the strategies of ruler cult adopted in the early Hellenistic period. -

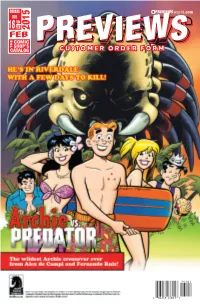

Customer Order Form

ORDERS PREVIEWS world.com DUE th 18 FEB 2015 FEB COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Feb15 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 1/8/2015 3:45:07 PM Feb15 IFC Future Dudes Ad.indd 1 1/8/2015 9:57:57 AM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS The Shield #1 l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS 1 Sonic/Mega Man: Worlds Collide: The Complete Epic TP l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS Crossed: Badlands #75 l AVATAR PRESS INC Extinction Parade Volume 2: War TP l AVATAR PRESS INC Lady Mechanika: The Tablet of Destinies #1 l BENITEZ PRODUCTIONS UFOlogy #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Lumberjanes Volume 1 TP l BOOM! STUDIOS 1 Masks 2 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Jungle Girl Season 3 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Uncanny Season 2 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Supermutant Magic Academy GN l DRAWN & QUARTERLY Rick & Morty #1 l ONI PRESS INC. Bloodshot Reborn #1 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT LLC GYO 2-in-1 Deluxe Edition HC l VIZ MEDIA LLC BOOKS Funnybooks: The Improbable Glories of the Best American Comic Books l COMICS Taschen’s The Bronze Age Of DC Comics 1970-1984 HC l COMICS Neil Gaiman: Chu’s Day at the Beach HC l NEIL GAIMAN Darth Vader & Friends HC l STAR WARS MAGAZINES Star Trek: The Official Starships Collection Special #5: Klingon Bird-of-Prey l EAGLEMOSS Ace Magazine #2 l COMICS Ultimate Spider-Man Magazine #3 l COMICS Doctor Who Special #40 l DOCTOR WHO 2 TRADING CARDS Topps 2015 Baseball Series 2 Trading Cards l TOPPS COMPANY APPAREL DC Heroes: Aquaman Navy T-Shirt l PREVIEWS EXCLUSIVE WEAR 2 DC Heroes: Harley Quinn “Cells” -

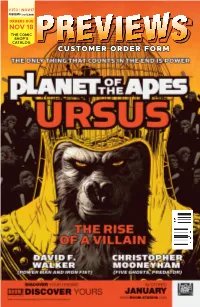

Customer Order Form

#350 | NOV17 PREVIEWS world.com ORDERS DUE NOV 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Nov17 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 10/5/2017 11:39:39 AM Nov17 Abstract C3.indd 1 10/5/2017 9:16:14 AM INVINCIBLE #144 HUNGRY GHOSTS #1 IMAGE COMICS DARK HORSE COMICS THE TERRIFICS #1 DC ENTERTAINMENT KOSCHEI THE DEATHLESS #1 THE WALKING DARK HORSE COMICS DEAD #175 IMAGE COMICS STAR WARS ADVENTURES: FORCES OF DESTINY ONE-SHOTS IDW ENTERTAINMENT SIDEWAYS #1 OLD MAN DC ENTERTAINMENT HAWKEYE #1 MARVEL COMICS Nov17 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 10/5/2017 3:24:03 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Strangers In Paradise XVX #1 l ABSTRACT STUDIOS Pestilence Volume 1 TP l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Uber Volume 6 TP l AVATAR PRESS INC Mech Cadet Yu Volume 1 TP l BOOM! STUDIOS Planet of the Apes: Ursus #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS 1 Dejah Thoris #0 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Battlestar Galactica Vs. Battlestar Galactica #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Sailor Moon Volume 1 Eternal Edition SC l KODANSHA COMICS Sci-Fu GN l ONI PRESS INC. Devilman Vs. Hades Volume 1 GN l SEVEN SEAS ENTERTAINMENT LLC Yokai Girls Volume 1 GN l SEVEN SEAS GHOST SHIP Warhammer 40,000: Deathwatch #1 l TITAN COMICS Assassin’s Creed Origins #1 l TITAN COMICS Mega Man Mastermix #1 l UDON ENTERTAINMENT INC 1 Ninjak Vs The Valiant Universe #1 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT LLC RWBY GN l VIZ MEDIA LLC BOOKS Marvel Black Panther: The Ultimate Guide HC l COMICS Marvels Black Panther: Illustrated History of a King HC l COMICS A Tribute To Mike Mignola’s Hellboy Show Catalogue -

Released 25Th March 2015

Released 25th March 2015 DARK HORSE COMICS NOV140102 ADVENTURES INTO THE UNKNOWN ARCHIVES HC VOL 04 NOV140090 ARCHIES PAL JUGHEAD ARCHIVES HC VOL 01 JAN150123 CAPTAIN MIDNIGHT #21 MARKED FOR DEATH PT 3 JAN150141 CONAN RED SONJA #3 JAN150140 CONAN THE AVENGER #12 DEC148728 EI8HT #1 2ND PTG JAN150158 ELFQUEST FINAL QUEST #8 JAN150105 GOON ONCE UPON A HARD TIME #2 NOV140022 GRINDHOUSE DRIVE IN BLEED OUT #3 JAN150159 HALO ESCALATION #16 JAN150120 MISTER X RAZED #2 NOV140020 MURDER BOOK TP JAN150085 PASTAWAYS #1 NOV140015 REFLECTIONS TP JAN150160 TOMB RAIDER #14 DC COMICS DEC140387 ADVENTURES OF SUPERMAN TP VOL 03 DEC140377 ALL STAR WESTERN TP VOL 06 END OF THE TRAIL (N52) JAN150261 AQUAMAN #40 JAN150326 ARKHAM MANOR #6 JAN150353 BATMAN 66 #21 NOV140308 BATMAN 66 MEETS THE GREEN HORNET HC JAN150323 BATMAN AND ROBIN #40 JAN150303 BATMAN ETERNAL #51 JAN150314 CATWOMAN #40 JAN150259 DEATHSTROKE #6 JAN150246 EARTH 2 WORLDS END #25 JAN150403 EFFIGY #3 (MR) JAN150265 FLASH #40 JAN150327 GOTHAM ACADEMY #6 JAN150329 GOTHAM BY MIDNIGHT #5 JAN150359 HE MAN THE ETERNITY WAR #4 JAN150268 INFINITY MAN AND THE FOREVER PEOPLE #9 JAN150257 JUSTICE LEAGUE DARK #40 JAN150233 MULTIVERSITY ULTRA COMICS #1 JAN150226 NEW 52 FUTURES END #47 (WEEKLY) JAN150348 RED LANTERNS #40 DEC148700 SECRET ORIGINS #10 2ND PTG JAN150273 SECRET ORIGINS #11 JAN150349 SINESTRO #11 JAN150275 STAR SPANGLED WAR STORIES GI ZOMBIE #8 JAN150407 SUICIDERS #2 (MR) NOV140304 SUPERMAN DOOMED HC (N52) IDW PUBLISHING JAN150493 ANGRY BIRDS #9 DEC140587 ANTI HERO TP DEC140500 BEN 10 CLASSICS TP -

Released 27Th May 2015 DARK HORSE COMICS MAR150030

Released 27th May 2015 DARK HORSE COMICS MAR150030 CAPTAIN MIDNIGHT #23 MAR150077 CONAN THE AVENGER #14 MAR150064 ELFQUEST FINAL QUEST #9 MAR150014 FIGHT CLUB 2 #1 MACK MAIN CVR MAR150084 FRANKENSTEIN UNDERGROUND #3 JAN150113 GRINDHOUSE DRIVE IN BLEED OUT #5(MR) MAR150061 HALO ESCALATION #18 MAR150027 MISTER X RAZED #4 MAR150028 ORDER OF THE FORGE #2 (MR) MAR150021 PASTAWAYS #3 JAN150142 SAVAGE SWORD OF CONAN TP VOL 19 MAR150062 TOMB RAIDER #16 JAN150173 TONY TAKEZAKIS NEON GENESIS EVANGELION TP DC COMICS FEB150250 BATGIRL TP VOL 05 DEADLINE (N52) MAR150255 BATMAN 66 #23 FEB150269 BATMAN ADVENTURES TP VOL 02 FEB150259 BATMAN LEGENDS OF THE DARK KNIGHT TP VOL 04 MAR150167 CONVERGENCE #8 (NOTE PRICE) MAR150231 CONVERGENCE ACTION COMICS #2 MAR150233 CONVERGENCE BLUE BEETLE #2 MAR150235 CONVERGENCE BOOSTER GOLD #2 MAR150237 CONVERGENCE CRIME SYNDICATE #2 MAR150239 CONVERGENCE DETECTIVE COMICS #2 MAR150241 CONVERGENCE INFINITY INC #2 MAR150243 CONVERGENCE JUSTICE SOCIETY OF AMERICA #2 MAR150245 CONVERGENCE PLASTIC MAN FREEDOM FIGHTERS #2 MAR150247 CONVERGENCE SHAZAM #2 MAR150249 CONVERGENCE WORLDS FINEST COMICS #2 MAR150301 EFFIGY #5 (MR) MAR150260 HE MAN THE ETERNITY WAR #6 MAR150253 INJUSTICE GODS AMONG US YEAR FOUR #2 DEC140262 MULTIVERSITY PAX AMERICANA DIRECTORS CUT #1 MAR150299 SANDMAN OVERTURE #5 COMBO PACK (MR) MAR150295 SANDMAN OVERTURE #5 CVR A (MR) MAR150296 SANDMAN OVERTURE #5 CVR B (MR) MAR150312 SUICIDERS #4 (MR) IDW PUBLISHING MAR150426 EDWARD SCISSORHANDS #8 WHOLE AGAIN MAR150428 EDWARD SCISSORHANDS TP VOL 01 PARTS UNKNOWN MAR150420 -

Manitowoc Kennel Club Friday, April 2, 2021

Manitowoc Kennel Club Friday, April 2, 2021 Group Results Sporting Spaniels (English Cocker) 27 BB/G1 GCHP CH K'mander Dawnglow Arnage. SR89298901 Retrievers (Chesapeake Bay) 25 BB/G2 GCHG CH Sandbar's Hardcore Hank MH. SR81693507 Setters (English) 26 BB/G3 GCH CH Ciara N' Honeygait Belle Of The Ball. SS07012602 Retrievers (Golden) 37 BB/G4 GCHG CH Futura Lime Me Entertain You CGC. SR86361206 Hound Whippets 18 1/W/BB/BW/G1 Woods Runner One And Only. HP56111307 Beagles (15 Inch) 11 BB/G2 GCHB CH Everwind's Living The Dream. HP55226602 Rhodesian Ridgebacks 32 BB/G3 GCHS CH Hilltop's Enchanting Circe of Dykumos. HP57068004 Afghan Hounds 7 BB/G4 GCHG CH Taji Better Man Mazshalna CGC. HP45099607 Working Great Danes 26 BB/G1 GCHG CH Landmark-Divine Acres Kiss Myself I'm So Pretty. WS56877803 Samoyeds 34 BB/G2 GCHG CH Sammantic Speed Of Life. WS59323801 Bernese Mountain Dogs 33 BB/G3 GCH CH Bernergardens Look To The Stars BN RI. WS62005402 Doberman Pinschers 46 BB/G4 GCHB CH Kandu's Glamour Puss V Mytoys. WS61064602 Terrier Australian Terriers 15 BB/G1 GCHS CH Temora Steal My Heart CA TKN. RN29651902 Border Terriers 12 BB/G2 GCHS CH Meadowlake High Times. RN31451901 American Staffordshire Terriers 19 BB/G3 CH Corralitos Tracking The Storm. RN33989402 Glen of Imaal Terriers 23 BB/G4 GCH CH Abberann Midnight Rider Of Glendalough. RN31978502 Toy Affenpinschers 7 BB/G1/BIS GCHS CH Point Dexter V. Tani Kazari. TS40341801 Papillons 17 BB/G2 GCHG CH Wingssong This Could Be Love. TS32017001 Maltese 7 BB/G3 GCHS CH Martin's Time Bomb Puff. -

December 3, 1992 CHAPTER VIII

December 3, 1992 CHAPTER VIII: EARLY HELLENISTIC DYNAMISM, 323-146 Aye me, the pain and the grief of it! I have been sick of Love's quartan now a month and more. He's not so fair, I own, but all the ground his pretty foot covers is grace, and the smile of his face is very sweetness. 'Tis true the ague takes me now but day on day off, but soon there'll be no respite, no not for a wink of sleep. When we met yesterday he gave me a sidelong glance, afeared to look me in the face, and blushed crimson; at that, Love gripped my reins still the more, till I gat me wounded and heartsore home, there to arraign my soul at bar and hold with myself this parlance: "What wast after, doing so? whither away this fond folly? know'st thou not there's three gray hairs on thy brow? Be wise in time . (Theocritus, Idylls, XXX). Writers about pederasty, like writers about other aspects of ancient Greek culture, have tended to downplay the Hellenistic period as inferior. John Addington Symonds, adhering to the view of the great English historian of ancient Greece, George Grote, that the Hellenistic Age was decadent, ended his Problem in Greek Ethics with the loss of Greek freedom at Chaeronea: Philip of Macedon, when he pronounced the panegyric of the Sacred Band at Chaeronea, uttered the funeral oration of Greek love in its nobler forms. With the decay of military spirit and the loss of freedom, there was no sphere left for that type of comradeship which I attempted to describe in Section IV. -

Warren Ellis Frankenstein's Womb Gn (Ogn) H MMW THOR V

H UNIVERSAL WAR ONE V. 1 HC H POWERS V. 12 TPB collects #1-3, $25 collects #25-30, $20 H M ADVS HULK V. 4 DIGEST H MMW AVENGERS V. 8 HC collects #13-16, $9 collects #69-79, $55 H M ADVS SPIDEY V. 11 DIGEST H MMW atlas era STRANGE TALES v.2 HC collects #41-44, $9 collects #11-20, $55 H ANITA BLACK VH GP V. 2 TPB Warren Ellis Frankenstein's Womb Gn (ogn) H MMW THOR V. 8 HC collects #7-12, $16 by Warren Ellis & Marek Oleksicki It began a few months earlier when, en route through Ger- H collects #163-172, $55 SPIDEY BND V . 2 TPB many to Switzerland, Mary, her future husband Percy Shelley, and her stepsister Clair Clair- H SECRET WARS OMNIBUS V. 2 HC collects #552-558, $20 mont approached a strange castle. And she was never the same again - because something H collects EVERYTHING!! REALLY, $100 CABLE V. 1 TP was haunting that tower, and Mary met it there. Fear, death and alchemy - the modern age is H ULTIMATE ORIGINS HC collects #1-5, $15 created here, in lost moments in a ruined castle on a day never recorded. collects #1-5, $25 H HEDGE KNIGHT 2 S. SWORD TPB H NOVA V. 1 HC collects #1-6, $16 Eureka #1 (4 issues) collects #1-12 & ANN 1, $35 H INFINITY CRUSADE V. 1 TPB by Andrew Cosby, Brendan Hay & Diego Barreto TV's smash sci-fi hit comes to BOOM! In what H ULTIMATES 3 V.