Sacher 20 Inhalt.Qxp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stravinsky, the Fire-Bird, "The Fire-Bird's Dance,"

/N81 AI2319 Ti VILSKY' USE OF IEhPIAN IN HIS ORCHESTRAL WORKS THE IS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of M1- JiROF JU.SIC by Wayne Griffith, B. Mus. Conway, Arkansas January, 1955 TABLE OF CONTENT4 Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . ,.. , , * . Chap ter I. THE USE OF PIANO1E A' Al ORCTHE TL I:ThUERIMT BEFOR 1910 . , , . , , l STRAICY II. S U6 OF 2E PIANO S E114ORCHES L ORK HIS OF "RUSIA PERIOD . 15 The Fire-Bird Pe~trouchka Le han u hossignol III. STAVIL C ' 0 USE OF TE PI 40IN 9M ORCHESTRAL .RKS OF HIS "NEO-CLASSIO" PERIOD . 56 Symphonyof Psalms Scherzo a la Russe Scenes IBfallet Symphony~in Three Movements BIIORPHYy * - . 100 iii 1I3T OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Berlioz, Leio, Finale, (from Berlioz' Treatise on Instrumentation, p . 157) . 4 2. Saint-Saena, ym phony in 0-minor, (from Prof. H. Kling's Modern Orchestration and Instrumentation, a a.~~~~*f0" 0. 7 p. 74) . 0 0 * * * 3. Moussorgsky, Boris Godunov, "Coronation Scene,'" 36-40 mm.f . -a - - --. " " . 10 4. oussorgsky, Boris Godunov, "Coronation :scene," mm. 241-247 . f . * . 11 5. imsky-Korsakoff, Sadko , (from rimkir -Korsakoff' s Principles of 0rchtiration, Lart II, p. 135) . 12 6. ximsky-Korsakoff, The Snow aiden, (from Zimsky torsatoff'c tTTrin~lecs ofhOrchestration, Part II, . 01) . - - . - . * - - . 12 7 . i s akosy-. o Rf, TVe <now %aiN , (f 0r 1;i s^ky Korsaoif ' s Prciniles of Orchestration, Part II, 'p. 58) . aa. .a. .a- -.-"- -a-a -r . .". 13 8. Stravinsky, The Fire-Bird, "The Fire-Bird's Dance," 9. -

JUNE 27–29, 2013 Thursday, June 27, 2013, 7:30 P.M. 15579Th

06-27 Stravinsky:Layout 1 6/19/13 12:21 PM Page 23 JUNE 2 7–29, 2013 Two Works by Stravinsky Thursday, June 27, 2013, 7:30 p.m. 15, 579th Concert Friday, June 28, 2013, 8 :00 p.m. 15,580th Concert Saturday, June 29, 2013, 8:00 p.m. 15,58 1st Concert Alan Gilbert , Conductor/Magician Global Sponsor Doug Fitch, Director/Designer Karole Armitage, Choreographer Edouard Getaz, Producer/Video Director These concerts are sponsored by Yoko Nagae Ceschina. A production created by Giants Are Small Generous support from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, Clifton Taylor, Lighting Designer The Susan and Elihu Rose Foun - Irina Kruzhilina, Costume Designer dation, Donna and Marvin Matt Acheson, Master Puppeteer Schwartz, the Mary and James G. Margie Durand, Make-Up Artist Wallach Family Foundation, and an anonymous donor. Featuring Sara Mearns, Principal Dancer* Filming and Digital Media distribution of this Amar Ramasar , Principal Dancer/Puppeteer* production are made possible by the generos ity of The Mary and James G. Wallach Family This concert will last approximately one and Foundation and The Rita E. and Gustave M. three-quarter hours, which includes one intermission. Hauser Recording Fund . Avery Fisher Hall at Lincoln Center Home of the New York Philharmonic June 2013 23 06-27 Stravinsky:Layout 1 6/19/13 12:21 PM Page 24 New York Philharmonic Two Works by Stravinsky Alan Gilbert, Conductor/Magician Doug Fitch, Director/Designer Karole Armitage, Choreographer Edouard Getaz, Producer/Video Director A production created by Giants Are Small Clifton Taylor, Lighting Designer Irina Kruzhilina, Costume Designer Matt Acheson, Master Puppeteer Margie Durand, Make-Up Artist Featuring Sara Mearns, Principal Dancer* Amar Ramasar, Principal Dancer/Puppeteer* STRAVINSKY Le Baiser de la fée (The Fairy’s Kiss ) (1882–1971) (1928, rev. -

Stravinsky Oedipus

London Symphony Orchestra LSO Live LSO Live captures exceptional performances from the finest musicians using the latest high-density recording technology. The result? Sensational sound quality and definitive interpretations combined with the energy and emotion that you can only experience live in the concert hall. LSO Live lets everyone, everywhere, feel the excitement in the world’s greatest music. For more information visit lso.co.uk LSO Live témoigne de concerts d’exception, donnés par les musiciens les plus remarquables et restitués grâce aux techniques les plus modernes de Stravinsky l’enregistrement haute-définition. La qualité sonore impressionnante entourant ces interprétations d’anthologie se double de l’énergie et de l’émotion que seuls les concerts en direct peuvent offrit. LSO Live permet à chacun, en toute Oedipus Rex circonstance, de vivre cette passion intense au travers des plus grandes oeuvres du répertoire. Pour plus d’informations, rendez vous sur le site lso.co.uk Apollon musagète LSO Live fängt unter Einsatz der neuesten High-Density Aufnahmetechnik außerordentliche Darbietungen der besten Musiker ein. Das Ergebnis? Sir John Eliot Gardiner Sensationelle Klangqualität und maßgebliche Interpretationen, gepaart mit der Energie und Gefühlstiefe, die man nur live im Konzertsaal erleben kann. LSO Live lässt jedermann an der aufregendsten, herrlichsten Musik dieser Welt teilhaben. Wenn Sie mehr erfahren möchten, schauen Sie bei uns Jennifer Johnston herein: lso.co.uk Stuart Skelton Gidon Saks Fanny Ardant LSO0751 Monteverdi Choir London Symphony Orchestra Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) The music is linked by a Speaker, who pretends to explain Oedipus Rex: an opera-oratorio in two acts the plot in the language of the audience, though in fact Oedipus Rex (1927, rev 1948) (1927, rev 1948) Cocteau’s text obscures nearly as much as it clarifies. -

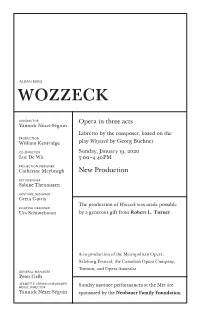

January 19, 2020 Luc De Wit 3:00–4:40 PM

ALBAN BERG wozzeck conductor Opera in three acts Yannick Nézet-Séguin Libretto by the composer, based on the production William Kentridge play Woyzeck by Georg Büchner co-director Sunday, January 19, 2020 Luc De Wit 3:00–4:40 PM projection designer Catherine Meyburgh New Production set designer Sabine Theunissen costume designer Greta Goiris The production of Wozzeck was made possible lighting designer Urs Schönebaum by a generous gift from Robert L. Turner A co-production of the Metropolitan Opera; Salzburg Festival; the Canadian Opera Company, Toronto; and Opera Australia general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Sunday matinee performances at the Met are Yannick Nézet-Séguin sponsored by the Neubauer Family Foundation 2019–20 SEASON The 75th Metropolitan Opera performance of ALBAN BERG’S wozzeck conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin in order of vocal appearance the captain the fool Gerhard Siegel Brenton Ryan wozzeck a soldier Peter Mattei Daniel Clark Smith andres a townsman Andrew Staples Gregory Warren marie marie’s child Elza van den Heever Eliot Flowers margret Tamara Mumford* puppeteers Andrea Fabi the doctor Gwyneth E. Larsen Christian Van Horn ac tors the drum- major Frank Colardo Christopher Ventris Tina Mitchell apprentices Wozzeck is stage piano solo Richard Bernstein presented without Jonathan C. Kelly Miles Mykkanen intermission. Sunday, January 19, 2020, 3:00–4:40PM KEN HOWARD / MET OPERA A scene from Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Berg’s Wozzeck Video Control Kim Gunning Assistant Video Editor Snezana Marovic Musical Preparation Caren Levine*, Jonathan C. Kelly, Patrick Furrer, Bryan Wagorn*, and Zalman Kelber* Assistant Stage Directors Gregory Keller, Sarah Ina Meyers, and J. -

The American Stravinsky

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY The Style and Aesthetics of Copland’s New American Music, the Early Works, 1921–1938 Gayle Murchison THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS :: ANN ARBOR TO THE MEMORY OF MY MOTHERS :: Beulah McQueen Murchison and Earnestine Arnette Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2012 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America ϱ Printed on acid-free paper 2015 2014 2013 2012 4321 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-0-472-09984-9 Publication of this book was supported by a grant from the H. Earle Johnson Fund of the Society for American Music. “Excellence in all endeavors” “Smile in the face of adversity . and never give up!” Acknowledgments Hoc opus, hic labor est. I stand on the shoulders of those who have come before. Over the past forty years family, friends, professors, teachers, colleagues, eminent scholars, students, and just plain folk have taught me much of what you read in these pages. And the Creator has given me the wherewithal to ex- ecute what is now before you. First, I could not have completed research without the assistance of the staff at various libraries. -

61 CHAPTER 4 CONNECTIONS and CONFLICT with STRAVINSKY Connections and Collaborations a Close Friendship Between Arthur Lourié A

CHAPTER 4 CONNECTIONS AND CONFLICT WITH STRAVINSKY Connections and Collaborations A close friendship between Arthur Lourié and Igor Stravinsky began once both had left their native Russian homeland and settled on French soil. Stravinsky left before the Russian Revolution occurred and was on friendly terms with his countrymen when he departed; from the premiere of the Firebird (1910) in Paris onward he was the favored representative of Russia abroad. "The force of his example bequeathed a russkiv slog (Russian manner of expression or writing) to the whole world of twentieth-century concert music."1 Lourié on the other hand defected in 1922 after the Bolshevik Revolution and, because he had abandoned his position as the first commissar of music, he was thereafter regarded as a traitor. Fortunately this disrepute did not follow him to Paris, where Stravinsky, as did others, appreciated his musical and literary talents. The first contact between the two composers was apparently a correspondence from Stravinsky to Lourié September 9, 1920 in regard to the emigration of Stravinsky's mother. The letter from Stravinsky thanks Lourié for previous help and requests further assistance in selling items from Stravinsky's 1 Richard Taruskin, Stravinsky and the Russian Traditions: A Biography of the 61 62 apartment in order to raise money for his mother's voyage to France.2 She finally left in 1922, which was the year in which Lourié himself defected while on government business in Berlin. The two may have met for the first time in 1923 when Stravinsky's Histoire du Soldat was performed at the Bauhaus exhibit in Weimar, Germany. -

Dossier Pédagogique the Rake's Progress

Dossier pédagogique Opéra / Nouvelle production THE RAKE’S PROGRESS DE IGOR STRAVINSKI DIRECTION MUSICALE ARIE VAN BEEK MISE EN SCÈNE DAVID LESCOT AVEC L’ORCHESTRE DE PICARDIE ET LE CHŒUR DE L’OPÉRA DE LILLE Sa 8, Ma 11, Je 13, Di 16 (16h), Me 19 OCTOBRE 2011 à 20h Contacts Service des relations avec les publics [email protected] Dossier réalisé avec la collaboration de Sébastien Bouvier, enseignant missionné à l’Opéra de Lille Septembre 2011 Sommaire Préparer votre venue à l’Opéra 3 THE RAKE’S PROGRESS Résumé 4 Synopsis 5 Igor Stravinski 6 La genèse de l’œuvre 7 Guide d’écoute 11 Vocabulaire 31 Pistes pédagogiques 33 Références 34 THE RAKE’S PROGRESS À L’OPÉRA DE LILLE Distribution 35 Mise en scène, note d’intention 36 Entretien avec Arie van Beek, directeur musical 38 Repères biographiques 40 POUR ALLER PLUS LOIN La voix à l’opéra 41 Qui fait quoi à l’opéra ? 42 L’Opéra de Lille, un lieu, une histoire 43 ANNEXE Fiche instruments 47 2 Préparer votre venue Ce dossier vous aidera à préparer votre venue avec les élèves. L’équipe de l’Opéra de Lille est à votre disposition pour toute information complémentaire et pour vous aider dans votre approche pédagogique. Si le temps vous manque, nous vous conseillons, prioritairement, de : - lire la fiche résumé et le synopsis détaillé - faire une écoute des extraits représentatifs de l’opéra (guide d’écoute) Recommandations Le spectacle débute à l’heure précise. Il est donc impératif d’arriver au moins 30 minutes à l’avance, les portes sont fermées dès le début du spectacle. -

Great-Rag-Sketches, Source Study for Stravinsky's Piano-Rag-Music Tom Gordon

Document généré le 23 sept. 2021 12:06 Intersections Canadian Journal of Music Revue canadienne de musique Great-Rag-Sketches, Source Study for Stravinsky's Piano-Rag-Music Tom Gordon Volume 26, numéro 1, 2005 Résumé de l'article Le processus compositionnel de Stravinsky durant sa période néo-classique est URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1013243ar ici mis en relief et étudié par le biais des esquisses, brouillons et autres copies DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1013243ar manuscrites de la Piano-Rag-Music. Ces autographes révèlent le matériel initial du compositeur, ses méthodes de travail, l’ampleur de ses préoccupations Aller au sommaire du numéro compositionnelles et les conditions étonnantes d’assemblage de l’œuvre. D’ailleurs, elles confirment que la fusion entre les trois éléments distincts opérée dans le titre de l’ouvrage par le trait d’union définit à la fois le contenu Éditeur(s) de l’œuvre et son objectif. La virtuosité pianistique et la vitalité rythmique de l’improvisation de type ragtime sont synthétisés en une forme musicale pure Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités qui est ni conventionnelle ni hybride, mais plutôt une résultante du matériel canadiennes en soi. ISSN 1911-0146 (imprimé) 1918-512X (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Gordon, T. (2005). Great-Rag-Sketches, Source Study for Stravinsky's Piano-Rag-Music. Intersections, 26(1), 62–85. https://doi.org/10.7202/1013243ar Copyright © Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des universités canadiennes, 2006 services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. -

MTO 18.4: Straus, Three Stravinsky Analyses

Volume 18, Number 4, December 2012 Copyright © 2012 Society for Music Theory Three Stravinsky Analyses: Petrushka, Scene 1 (to Rehearsal No. 8); The Rake’s Progress, Act III, Scene 3 (“In a foolish dream”); Requiem Canticles, “Exaudi” Joseph N. Straus NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.12.18.4/mto.12.18.4.straus.php KEYWORDS: Stravinsky, Petrushka, The Rake’s Progress, Requiem Canticles, analysis, melody, harmony, symmetry, collection, recomposition, prolongation, rhythm and meter, textural blocks ABSTRACT: Most published work in our field privileges theory over analysis, with analysis acting as a subordinate testing ground and exemplification for a theory. Reversing that customary polarity, this article analyzes three works by Stravinsky (Petrushka, The Rake’s Progress, Requiem Canticles) with a relative minimum of theoretical preconceptions and with the simple aim, in David Lewin’s words, of “hearing the piece[s] better.” Received February 2012 [1] In his classic description of the relationship between theory and analysis, David Lewin states that theory describes the way that musical sounds are “conceptually structured categorically prior to any one specific piece,” whereas analysis turns our attention to “the individuality of the specific piece of music under study,” with a goal “simply to hear the piece better, both in detail and in the large” (Lewin 1968, 61-63, italics in original). In practice, we create theories in order to engender and empower analysis and we use analysis as a proving ground for our theories. In the field of music theory as currently constituted, theory-based analysis and analysis-oriented theory are the principal and the statistically predominant activities. -

The Late Choral Works of Igor Stravinsky

THE LATE CHORAL WORKS OF IGOR STRAVINSKY: A RECEPTION HISTORY _________________________________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia ________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts ____________________________ by RUSTY DALE ELDER Dr. Michael Budds, Thesis Supervisor DECEMBER 2008 The undersigned, as appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled THE LATE CHORAL WORKS OF IGOR STRAVINSKY: A RECEPTION HISTORY presented by Rusty Dale Elder, a candidate for the degree of Master of Arts, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. _________________________________________ Professor Michael Budds ________________________________________ Professor Judith Mabary _______________________________________ Professor Timothy Langen ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude to each member of the faculty who participated in the creation of this thesis. First and foremost, I wish to recognize the ex- traordinary contribution of Dr. Michael Budds: without his expertise, patience, and en- couragement this study would not have been possible. Also critical to this thesis was Dr. Judith Mabary, whose insightful questions and keen editorial skills greatly improved my text. I also wish to thank Professor Timothy Langen for his thoughtful observations and support. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………………...ii ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………………...v CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION: THE PROBLEM OF STRAVINSKY’S LATE WORKS…....1 Methodology The Nature of Relevant Literature 2. “A BAD BOY ALL THE WAY”: STRAVINSKY’S SECOND COMPOSITIONAL CRISIS……………………………………………………....31 3. AFTER THE BOMB: IN MEMORIAM DYLAN THOMAS………………………45 4. “MURDER IN THE CATHEDRAL”: CANTICUM SACRUM AD HONOREM SANCTI MARCI NOMINIS………………………………………………………...60 5. -

Download Program Notes

L’Oiseau de feu (The Firebird) (complete ballet score) Igor Stravinsky s musicians go, Igor Stravinsky was a Nightingale (1914), Pulcinella (1920), Mavra A rather late bloomer. He didn’t begin pia- (1922), Reynard (1922), The Wedding (1923), no lessons until he was nine, but these were Oedipus Rex (1927), and Apollo (1928). soon supplemented by private tutoring in The Ballets Russes made a specialty of harmony and counterpoint. His parents sup- pieces inspired by Russian folklore (pri- ported his musical inclinations, all the more meval Russian history being a cultural ob- laudable since they knew what their teenag- session of the moment) and The Firebird er was getting into. (Stravinsky’s father was a was perfectly suited to the company’s de- bass singer at the opera houses of Kiev and, signs. The tale involves the dashing Prince later, St. Petersburg; his mother was an accom- Ivan (Ivan Tsarevich), who finds himself plished amateur pianist.) One of Stravinsky’s one night wandering through the garden friends at school was the son of the celebrat- of King Kashchei, an evil monarch whose ed composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. When power resides in a magic egg that he guards Stravinsky’s father died, in December 1902, in an elegant box. In Kashchei’s garden, the Rimsky-Korsakov became a mentor, both per- Prince captures a Firebird, which pleads sonal and musical, to the aspiring composer. for its life. The Prince agrees to spare it if By 1907 Stravinsky (already 25 years old) was it gives him one of its magic tail feathers, ready to bestow an opus number on one of his which it consents to do. -

Doctor of Musical Arts

In the Fingertips: A Discussion of Stravinsky’s Violin Writing in His Ballet Transcriptions for Violin and Piano A document submitted to the Graduate school of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Division of Performance Studies of the College-Conservatory of Music May 2012 by Kuan-Chang Tu B.F.A. Taipei National University of the Arts, 2001 M.M., University of Cincinnati, College-Conservatory of Music, 2005 Advisor: Piotr Milewski, D.M.A. Abstract Igor Stravinsky always embraced the opportunity to cast his music in a different light. This is nowhere more evident than in the nine pieces for violin and piano extracted from his early ballets. In the 1920s, the composer rendered three of these himself; in the 1930s, he collaborated on five of them with Polish-American violinist Samuel Dushkin; and in 1947, he wrote his final one for French violinist Jeanne Gautier. In the process, Stravinsky took an approach that deviated from traditional recasting. Instead of writing thoroughly playable music, Stravinsky chose to recreate in the spirit of the instrument, and the results are mixed. The three transcriptions from the 1920s are extremely awkward and difficult to play, and thus rarely performed. The six later transcriptions, by contrast, apply much more logically to the instrument and remain popular in the violin literature. While the history of these transcriptions is fascinating and vital for a fuller understanding, this document has a more pedagogical aim. That is, it intends to use Stravinsky and these transcriptions as guidance and advice for future composers who write or arrange for the violin.