Download Program Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

October 17, 1993 2096Th Concert

The Nymph’s Reply to the Shepherd — Sir Walter Raleigh THE WILLIAM NELSON CROMWELL and If all the world and love were young, And truth in every shepherd’s tongue, F. LAMMOT BELIN CONCERTS These pretty pleasures might me move To live with thee and be thy love. at the Time drives the flocks from field to fold National Gallery of Art When rivers rage and rocks grow cold, And Philomel becometh dumb; The rest complains of cares to come. The flowers do fade, and wanton fields To wayward winter reck’ning yields; A honey tongue, a heart of gall, Is fancy’s spring, but sorrow’s fall.... Thy belt of straw and ivy buds, Thy coral clasps and amber studs, All these in me no means can move To come to thee and be thy love. But could youth last and love still breed, Had joys no date nor age no need, Then these delights my mind might move To come with thee and be thy love. I Know a Bird — Dorothy Diemer Hendry 2096th Concert I know a bird that sings all night, NATIONAL GALLERY VOCAL ARTS ENSEMBLE Mad with love in the full moonlight. He steals his rolling roundelay GEORGE MANOS, Artistic Director and pianist From proper birds that sing by day. ROSA LAMOREAUX, soprano Chip, chip, cheerily, cheerily, coo-coo, coo-coo. BEVERLY BENSO, contralto How do I know he pours his song, SAMUEL GORDON, tenor Mad as moonlight, all night long? I myself the whole night through ROBERT KENNEDY, baritone Hear him while I long for you. -

Rachel Barton Violin Patrick Sinozich, Piano DDD Absolutely Digital™ CDR 90000 041 INSTRUMENT of the DEVIL 1 Saint-Saëns: Danse Macabre, Op

Cedille Records CDR 90000 041 Rachel Barton violin Patrick Sinozich, piano DDD Absolutely Digital™ CDR 90000 041 INSTRUMENT OF THE DEVIL 1 Saint-Saëns: Danse Macabre, Op. 40 (7:07) Tartini: Sonata in G minor, “The Devil’s Trill”* (15:57) 2 I. Larghetto Affectuoso (5:16) 3 II. Tempo guisto della Scuola Tartinista (5:12) 4 III. Sogni dellautore: Andante (5:25) 5 Liszt/Milstein: Mephisto Waltz (7:21) 6 Bazzini: Round of the Goblins, Op. 25 (5:05) 7 Berlioz/Barton-Sinozich: Dream of a Witches’ Sabbath from Symphonie Fantastique, Op. 14 (10:51) 8 De Falla/Kochanski: Dance of Terror from El Amor Brujo (2:11) 9 Ernst: Grand Caprice on Schubert’s Der Erlkönig, Op. 26 (4:11) 10 Paganini: The Witches, Op. 8 (10:02) 1 1 Stravinsky: The Devil’s Dance from L’Histoire du Soldat (trio version)** (1:21) 12 Sarasate: Faust Fantasy (13:30) Rachel Barton, violin Patrick Sinozich, piano *David Schrader, harpsichord; John Mark Rozendaal, cello **with John Bruce Yeh, clarinet TT: (78:30) Cedille Records is a trademark of The Chicago Classical Recording Foundation, a not-for-profit foun- dation devoted to promoting the finest musicians and ensembles in the Chicago area. The Chicago Classical Recording Foundation’s activities are supported in part by grants from the WPWR-TV Chan- nel 50 Foundation and the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency. Zig and zig and zig, Death in cadence Knocking on a tomb with his heel, Death at midnight plays a dance tune Zig and zig and zig, on his violin. -

Stravinsky, the Fire-Bird, "The Fire-Bird's Dance,"

/N81 AI2319 Ti VILSKY' USE OF IEhPIAN IN HIS ORCHESTRAL WORKS THE IS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of M1- JiROF JU.SIC by Wayne Griffith, B. Mus. Conway, Arkansas January, 1955 TABLE OF CONTENT4 Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . ,.. , , * . Chap ter I. THE USE OF PIANO1E A' Al ORCTHE TL I:ThUERIMT BEFOR 1910 . , , . , , l STRAICY II. S U6 OF 2E PIANO S E114ORCHES L ORK HIS OF "RUSIA PERIOD . 15 The Fire-Bird Pe~trouchka Le han u hossignol III. STAVIL C ' 0 USE OF TE PI 40IN 9M ORCHESTRAL .RKS OF HIS "NEO-CLASSIO" PERIOD . 56 Symphonyof Psalms Scherzo a la Russe Scenes IBfallet Symphony~in Three Movements BIIORPHYy * - . 100 iii 1I3T OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Berlioz, Leio, Finale, (from Berlioz' Treatise on Instrumentation, p . 157) . 4 2. Saint-Saena, ym phony in 0-minor, (from Prof. H. Kling's Modern Orchestration and Instrumentation, a a.~~~~*f0" 0. 7 p. 74) . 0 0 * * * 3. Moussorgsky, Boris Godunov, "Coronation Scene,'" 36-40 mm.f . -a - - --. " " . 10 4. oussorgsky, Boris Godunov, "Coronation :scene," mm. 241-247 . f . * . 11 5. imsky-Korsakoff, Sadko , (from rimkir -Korsakoff' s Principles of 0rchtiration, Lart II, p. 135) . 12 6. ximsky-Korsakoff, The Snow aiden, (from Zimsky torsatoff'c tTTrin~lecs ofhOrchestration, Part II, . 01) . - - . - . * - - . 12 7 . i s akosy-. o Rf, TVe <now %aiN , (f 0r 1;i s^ky Korsaoif ' s Prciniles of Orchestration, Part II, 'p. 58) . aa. .a. .a- -.-"- -a-a -r . .". 13 8. Stravinsky, The Fire-Bird, "The Fire-Bird's Dance," 9. -

1 Requirements for the Call to Establish the Oboe/Cor Anglais

Requirements for the call to establish the oboe/cor anglais substitution pool for the Barcelona Symphony Orchestra 1- Purpose of the call The purpose of this call is the creation of a substitution pool, with the category of Senior Professor of Music (Tutti) in the specialty of oboe/cor anglais, to be hired in the mode of temporary employment, based on the needs of the Consorci de L’Auditori i l’Orquestra in the department of the Barcelona Symphony Orchestra (hereinafter OBC). The incorporation of temporary work personnel shall be limited to the circumstances established in the regulations, in line with the general principle of hiring staff at L'Auditori by means of passing through selective processes and whenever there are reasons for the maintenance of essential services, specifically: Temporary replacement of the appointees; Increase in staff for artistic needs for the temporary execution of programmes; The incorporations in any case must be made in accordance with the conditions stemming from the budgetary regulations. The incorporation of temporary work personnel shall be governed by the labour relations of a special nature for artists in public performances provided for in the Workers’ Statute and regulated by Royal Decree 1435/1985. The remuneration and the working hours shall be that agreed upon in the collective bargaining agreement. 2- Requirements for participation All requirements must be met by the deadline for submission of applications and must be maintained for as long as the employment relationship with the Consorci de l’Auditori i l’Orquestra should last. - Be at least 16 years of age and not exceed the age established for forced retirement. -

The Curtis Institute of Music Roberto Díaz, President

The Curtis Institute of Music Roberto Díaz, President This concert will be available online for free streaming 2008–09 Student Recital Series and download on Thursday, February 19. The Edith L. and Robert Prostkoff Memorial Concert Series Visit www.instantencore.com/curtis after 12 noon and enter this download code in the upper-right corner of the webpage: Feb09CTour Forty-Fourth Student Recital: Curtis On Tour Click “Go” and follow the instructions on the screen to save music Wednesday, February 18 at 8 p.m. Field Concert Hall onto your computer. Divertimento for Violin and Piano Igor Stravinsky Next Student Recital Sinfonia (1882–1971) Friday, February 20 at 8 p.m. Danses suisses 20/21: The Curtis Contemporary Music Ensemble— Scherzo Second Viennese School, Program III Pas de deux: Adagio—Variation—Coda Field Concert Hall Josef Špaček, violin Kuok-man Lio, piano Berg Sieben frühe Lieder Amanda Majeski, soprano Three Pieces for Clarinet Solo Stravinsky Mikael Eliasen, piano Yao Guang Zhai, clarinet String Quartet, Op. 3 From the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám David Ludwig Joel Link, violin (world premiere) (b. 1972) Bryan A. Lee, violin Secrets of Creation Milena Pajaro-van de Stadt, viola Turning of Time Camden Shaw, cello Labor of Life Floating Particles Schoenberg Das Buch der hängenden Gärten, Op. 15 Carpe Diem Charlotte Dobbs, soprano Allison Sanders, mezzo-soprano David Moody, piano Yao Guang Zhai, clarinet William Short, bassoon Phantasy, Op. 47 Christopher Stingle, trumpet Elizabeth Fayette, violin Ryan Seay, trombone Pallavi Mahidhara, piano Benjamin Folk, percussion Josef Špaček, violin Programs are subject to change. Harold Hall Robinson, double bass Call the Recital Hotline, 215-893-5261, for the most up-to-date information. -

IGOR STRAVINSKY Symphony of Psalms

IGOR STRAVINSKY Symphony of Psalms BORN: June 17, 1882, in Oranienbaum (now Lomonosov), Saint Petersburg, Russia DIED: April 6, 1971, in New York City WORK COMPOSED: 1930 WORLD PREMIERE: December 13, 1930, at the Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels, Belgium; Société Philharmonique de Bruxelles, Ernest Ansermet conducting The latter years of the 1920s were an emotionally trying time for Stravinsky. He was carrying on an open affair with his mistress in Paris while his wife Katya was in the south of France dying of tuberculosis. (Katya was Stravinsky’s cousin, they married in 1906. She was diagnosed with the disease in 1914 after the birth of their fourth child and was confined to a sanatorium in the Alps where she died in March 1939.) He also was finding little success with his works from this time. Vivid musical evocations of disease, deterioration, debilitation, decay and denial abound in his 1927 work Oedipus Rex, which was a failure at its premiere in Paris. Serge Koussevitzky, Stravinsky’s publisher and conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra (also a virtuoso double bassist!), made a suggestion to Stravinsky that he should write something popular in order to have a success. The thought was for Stravinsky to write something the people could understand. However, Stravinsky thought it should be about something universally admired; he felt that society had lost the ability to share a sacred experience. Stravinsky was a devout member of the Russian Orthodox Church during most of his life. No doubt that this inspired him to compose the Symphony of Psalms. Even though it is a large choral piece, he called it a symphony to appease Koussevitzky because the request was for an orchestral work. -

World Première Stravinsky's Les Noces August

World première Stravinsky's Les Noces August & September 2009 The performances of Svadebka! The Village wedding which take place in Augustus and September during a tour of The Netherlands, can be seen in Amsterdam, Utrecht, The Hague and Electra in Groningen. The performances in the Hermitage in Amsterdam are nearly sold out. Ninety years after its conception the 1919 version of Stravinsky's Les Noces will finally be performed in a recently completed and approved version. After a long procedure, the Stravinsky heirs have recently granted permission for the 1919 version of Les Noces to be completed, resulting in the long awaited fulfillment of artistic director Peppie Wiersma's dream. In 1919 Igor Stravinsky started his second draft of Svadebka (Les Noces) in an instrumentation for the unusual scoring of pianola, two cimbaloms, harmonium and percussion. He finished the first two tableaux and then, due to problems with synchronization with the pianola and the unavailability of two good cimbalom players, abandoned this version. It took him four years to finish the final score for 4 piano’s and six percussions. The version of 1919 has since never been finished even though it offers great possibilities for a much more appropriate staging than the 1923 version with it’s 4 grand piano’s and large percussion set-up. The idea arose to re-create the 1919 version and to instrumentate the last two tableaux. With its small band-like appearance and twangy Balkan cimbalom sound the 1919 seems ideal to create a real village wedding atmosphere. The balance problems that almost always occur in the 1923 version would be easily solved and the choir could be much smaller and take part of the theatrical action. -

Le Rossignol As Told by David Hockney the Opera Takes Place In

Le Rossignol As told by David Hockney The opera takes place in ancient China and begins with a fisherman singing about the beauty of the nightingale’s song. Only he and a little servant girl who works in the palace kitchen know about this wonderful bird. The emperor of China lives in a porcelain palace. Everything about the palace is beautiful. The flowers in the garden have such a subtle perfume that little bells are hung on them, just in case you don’t notice. All the travelers who come to the kingdom write about how beautiful the palace is. And the poets who come say the most beautiful thing of all is the nightingale that sings by the seashore. So the emperor, who only reads books in the palace – he doesn’t go out of the palace – calls the chamberlain and asks why the most wonderful thing in his kingdom is something he does not know about. The emperor’s court tries to find out about the nightingale – but the only one who knows about it is the little girl who washes dishes in the kitchen. They ask everybody in the palace, but the response is we never heard the nightingale – we don’t know about it. Finally they find the little girl who says oh, yes, the nightingale that sings by the seashore is so beautiful. And they ask if she will take them to the nightingale. As a reward they promise to make her Lady High dishwasher and to give her 1 the privilege of watching the emperor eat. -

JUNE 27–29, 2013 Thursday, June 27, 2013, 7:30 P.M. 15579Th

06-27 Stravinsky:Layout 1 6/19/13 12:21 PM Page 23 JUNE 2 7–29, 2013 Two Works by Stravinsky Thursday, June 27, 2013, 7:30 p.m. 15, 579th Concert Friday, June 28, 2013, 8 :00 p.m. 15,580th Concert Saturday, June 29, 2013, 8:00 p.m. 15,58 1st Concert Alan Gilbert , Conductor/Magician Global Sponsor Doug Fitch, Director/Designer Karole Armitage, Choreographer Edouard Getaz, Producer/Video Director These concerts are sponsored by Yoko Nagae Ceschina. A production created by Giants Are Small Generous support from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, Clifton Taylor, Lighting Designer The Susan and Elihu Rose Foun - Irina Kruzhilina, Costume Designer dation, Donna and Marvin Matt Acheson, Master Puppeteer Schwartz, the Mary and James G. Margie Durand, Make-Up Artist Wallach Family Foundation, and an anonymous donor. Featuring Sara Mearns, Principal Dancer* Filming and Digital Media distribution of this Amar Ramasar , Principal Dancer/Puppeteer* production are made possible by the generos ity of The Mary and James G. Wallach Family This concert will last approximately one and Foundation and The Rita E. and Gustave M. three-quarter hours, which includes one intermission. Hauser Recording Fund . Avery Fisher Hall at Lincoln Center Home of the New York Philharmonic June 2013 23 06-27 Stravinsky:Layout 1 6/19/13 12:21 PM Page 24 New York Philharmonic Two Works by Stravinsky Alan Gilbert, Conductor/Magician Doug Fitch, Director/Designer Karole Armitage, Choreographer Edouard Getaz, Producer/Video Director A production created by Giants Are Small Clifton Taylor, Lighting Designer Irina Kruzhilina, Costume Designer Matt Acheson, Master Puppeteer Margie Durand, Make-Up Artist Featuring Sara Mearns, Principal Dancer* Amar Ramasar, Principal Dancer/Puppeteer* STRAVINSKY Le Baiser de la fée (The Fairy’s Kiss ) (1882–1971) (1928, rev. -

Stravinsky's Choral Music

TORONTO REGION NEWSLETTER February-March 2021 In the Spotlight: Stravinsky’s 1 What is CAMMAC? 13 Choral Music Of Note: George Meanwell Interview 5 Playing and singing opportunities 13 Reader response: Throat singing 11 Newsletter Deadline 14 Music Links 12 Management Committee 15 IN THE SPOTLIGHT: STRAVINSKY’S CHORAL MUSIC Submitted by Peter H. Solomon, Jr. If COVID-19 had not led to the cancellation of scheduled CAMMAC readings for choir and orchestra, we were set in spring 2021 to perform Igor Stravinsky’s masterpiece The Symphony of Psalms. So, this seemed like a good time to review the choral music of the master and to suggest pieces worthy of exploration by musicians and music lovers—activity that many of us have more time to pursue. Stravinsky wrote major works of this kind in each period of his long musical life—the Russian, the neoclassical, and the serial phases. The works always include instruments along with voices, though often in sparing and unusual combinations. Here I will focus on four pieces of music—Les Noces (The Wedding), first performed in 1923 and the culmination of Stravinsky’s Russian music; the Symphony of Psalms, 1930, perhaps the most beautiful of his neo classical pieces; the Mass, 1948, the most fully choral of his major works; and the Requiem Canticles, 1966, his last large composition. Les Noces (The Wedding or Svadebka) represents to some observers, including me, the pinnacle of Stravinsky’s Russian phase, a piece that is wilder than the Rite of Spring, though continuing in its vein. Not an opera and not a ballet, the work recreates the spectacle of a Russian peasant wedding, a sacrament that it depicts from the first preparations by women and men alike through the bride’s departure from home and the celebratory meal. -

Stravinsky Oedipus

London Symphony Orchestra LSO Live LSO Live captures exceptional performances from the finest musicians using the latest high-density recording technology. The result? Sensational sound quality and definitive interpretations combined with the energy and emotion that you can only experience live in the concert hall. LSO Live lets everyone, everywhere, feel the excitement in the world’s greatest music. For more information visit lso.co.uk LSO Live témoigne de concerts d’exception, donnés par les musiciens les plus remarquables et restitués grâce aux techniques les plus modernes de Stravinsky l’enregistrement haute-définition. La qualité sonore impressionnante entourant ces interprétations d’anthologie se double de l’énergie et de l’émotion que seuls les concerts en direct peuvent offrit. LSO Live permet à chacun, en toute Oedipus Rex circonstance, de vivre cette passion intense au travers des plus grandes oeuvres du répertoire. Pour plus d’informations, rendez vous sur le site lso.co.uk Apollon musagète LSO Live fängt unter Einsatz der neuesten High-Density Aufnahmetechnik außerordentliche Darbietungen der besten Musiker ein. Das Ergebnis? Sir John Eliot Gardiner Sensationelle Klangqualität und maßgebliche Interpretationen, gepaart mit der Energie und Gefühlstiefe, die man nur live im Konzertsaal erleben kann. LSO Live lässt jedermann an der aufregendsten, herrlichsten Musik dieser Welt teilhaben. Wenn Sie mehr erfahren möchten, schauen Sie bei uns Jennifer Johnston herein: lso.co.uk Stuart Skelton Gidon Saks Fanny Ardant LSO0751 Monteverdi Choir London Symphony Orchestra Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) The music is linked by a Speaker, who pretends to explain Oedipus Rex: an opera-oratorio in two acts the plot in the language of the audience, though in fact Oedipus Rex (1927, rev 1948) (1927, rev 1948) Cocteau’s text obscures nearly as much as it clarifies. -

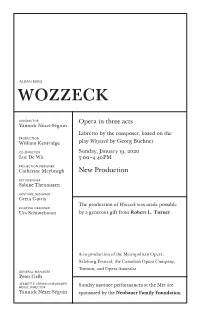

January 19, 2020 Luc De Wit 3:00–4:40 PM

ALBAN BERG wozzeck conductor Opera in three acts Yannick Nézet-Séguin Libretto by the composer, based on the production William Kentridge play Woyzeck by Georg Büchner co-director Sunday, January 19, 2020 Luc De Wit 3:00–4:40 PM projection designer Catherine Meyburgh New Production set designer Sabine Theunissen costume designer Greta Goiris The production of Wozzeck was made possible lighting designer Urs Schönebaum by a generous gift from Robert L. Turner A co-production of the Metropolitan Opera; Salzburg Festival; the Canadian Opera Company, Toronto; and Opera Australia general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Sunday matinee performances at the Met are Yannick Nézet-Séguin sponsored by the Neubauer Family Foundation 2019–20 SEASON The 75th Metropolitan Opera performance of ALBAN BERG’S wozzeck conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin in order of vocal appearance the captain the fool Gerhard Siegel Brenton Ryan wozzeck a soldier Peter Mattei Daniel Clark Smith andres a townsman Andrew Staples Gregory Warren marie marie’s child Elza van den Heever Eliot Flowers margret Tamara Mumford* puppeteers Andrea Fabi the doctor Gwyneth E. Larsen Christian Van Horn ac tors the drum- major Frank Colardo Christopher Ventris Tina Mitchell apprentices Wozzeck is stage piano solo Richard Bernstein presented without Jonathan C. Kelly Miles Mykkanen intermission. Sunday, January 19, 2020, 3:00–4:40PM KEN HOWARD / MET OPERA A scene from Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Berg’s Wozzeck Video Control Kim Gunning Assistant Video Editor Snezana Marovic Musical Preparation Caren Levine*, Jonathan C. Kelly, Patrick Furrer, Bryan Wagorn*, and Zalman Kelber* Assistant Stage Directors Gregory Keller, Sarah Ina Meyers, and J.