The Inside Story of the Casefrom Courtroom Cowboy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Nightmare on 17Th Street

SEXUAL ABUSE OF MINORS BY CLERGY IN THE ARCHDIOCESE OF PHILADELPHIA OR THE NIGHTMARE ON 17TH STREET Thomas P. Doyle, J.C.D., C.A.D.C. February 20, 2017 1 Introductory Remarks The Archdiocese of Philadelphia is one of the oldest ecclesiastical jurisdictions in the United States. It was erected as a diocese in 1808 and elevated to an archdiocese in 1875. It has long had the reputation of being one of the most staunchly “Catholic” and conservative dioceses in the country. The Archdiocese also has the very dubious distinction of having been investigated by not one but three grand juries in the first decade of the new millennium. The first investigation (Grand Jury 1, 2001-2002) was prompted by the District Attorney’s desire to find factual information about sexual abuse by Catholic clergy in the Archdiocese. The second grand jury (Grand Jury 2, 2003-2005) continued the investigation that the first could not finish before its term expired. The third grand jury investigation (Grand Jury 3, 2010-2011) was triggered by reports to the District Attorney that sexual abuse by priests was still being reported in spite of assurances by the Cardinal Archbishop (Rigali) after the second Grand Jury Report was published that all children in the Archdiocese were safe because there were no priest sexual abusers still in ministry. Most of what the three Grand Juries discovered about the attitude and practices of the archbishop and his collaborators could be found in nearly every archdiocese and diocese in the United States. Victims are encouraged to approach the Church’s victim assistance coordinators and assured of confidentiality and compassionate support yet their stories and other information are regularly shared with the Church’s attorneys in direct violation of the promise made by the Church. -

Pope Cover up Charge Denied

SERVING THE PEOPLE OF GOD IN THE COUNTIES OF BROWARD, COLLIER, DADE, GLADES, HENDRY; MARTIN, MONROE AND PALM BEACH Volume XX Number 26 September 14, 1979 Price 25c Pope Cover Up Charge Denied PHILADELPHIA -<NC)-Pope United States and 226 members be granted without the written ob- Guilfoyle of Camden, N.J., and John Paul II did not "cover up" a worldwide. Its headquarters are at servations of Cardinal John Krol of Father Paul Boyle, superior of the scandal involving the U. S. branch of the shrine of Our Lady of Philadelphia on the request; Passionist Fathers." a Polish religious order, said a Czestochowa at Jasna Gora, Poland, • No appointments to positions Pope Paul VI made those ap- spokesman for the Philadelphia which has been under the order's of responsibility among the Pauline pointments in October'1974 Archdiocese, where the order care since 1382. In the United Fathers in the United States be "'While this visitation was in operates a large shrine. States, the order owns and operates made without consultation with the process, corrections were made in The spokesman, Msgr. Charles the National Shrine of Our Lady of bishop of the place in which the the management of the National B. Mynaugh, archdiocesan com- Czestochowa in Doylestown, Pa., a appointment would be effective. Shrine of Our Lady of munications director, made public Philadelphia suburb. The shrine in "It is no secret that there were Czestochowa," Msgr. Mynaugh the provisions of a Vatican decree Poland is dear to the heart of the problems of management and in- said. He noted also that in 1976 dated May 21 and issued with the Polish Pope John Paul, who visited vestment at the Doylestown shrine," Cardinal' Krol launched a fund- approval of Pope John Paul. -

Volume 24 Supplement

2 GATHERED FRAGMENTS Leo Clement Andrew Arkfeld, S.V.D. Born: Feb. 4, 1912 in Butte, NE (Diocese of Omaha) A Publication of The Catholic Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania Joined the Society of the Divine Word (S.V.D.): Feb. 2, 1932 Educated: Sacred Heart Preparatory Seminary/College, Girard, Erie County, PA: 1935-1937 Vol. XXIV Supplement Professed vows as a Member of the Society of the Divine Word: Sept. 8, 1938 (first) and Sept. 8, 1942 (final) Ordained a priest of the Society of the Divine Word: Aug. 15, 1943 by Bishop William O’Brien in Holy Spirit Chapel, St. Mary Seminary, Techny, IL THE CATHOLIC BISHOPS OF WESTERN PENNSYLVANIA Appointed Vicar Apostolic of Central New Guinea/Titular Bishop of Bucellus: July 8, 1948 by John C. Bates, Esq. Ordained bishop: Nov. 30, 1948 by Samuel Cardinal Stritch in Holy Spirit Chapel, St. Mary Seminary Techny, IL The biographical information for each of the 143 prelates, and 4 others, that were referenced in the main journal Known as “The Flying Bishop of New Guinea” appears both in this separate Supplement to Volume XXIV of Gathered Fragments and on the website of The Cath- Title changed to Vicar Apostolic of Wewak, Papua New Guinea (PNG): May 15, 1952 olic Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania — www.catholichistorywpa.org. Attended the Second Vatican Council, Sessions One through Four: 1962-1965 Appointed first Bishop of Wewak, PNG: Nov. 15, 1966 Appointed Archbishop of Madang, PNG, and Apostolic Administrator of Wewak, PNG: Dec. 19, 1975 Installed: March 24, 1976 in Holy Spirit Cathedral, Madang Richard Henry Ackerman, C.S.Sp. -

Archhishop Schulte Is Honored by Pope

ArchhishopSchulte is honoredby pope ') r). I ,) t)tstl0DS l C'tt,rditrctl t'cl)euls upP} I,I t,t n'teI Il; (ts ilr'() ntllllcrl '/sslsluttL 'l 'lrr0 u,t l'rit ttificul t te to L,l.S.Sclcs \\,\Slil\(i.l'()N-tlis Iloli, llfsii l)opc.lolrrr ^\\lll lras tlir itlctl lltc .\r'r'lrrlirrt:cst'of Al{CHBISHOP gCHUI-TE*fronr I'ltillttlclPhiit ltr tlttircltittg- lhc Pope a rtew honor. ft'ont it lht' ('orrrrtics of l{rr('ll l(} {lrr' lirri:lt flor.al rl1'1'111.11- []t'rlis t';rLlirr1.l.t.lt1:lr. \rrt'1l1ttrtp. t ions. l(!n iilltlS,'lrrrrhrll sri lr\ lo fofnl r' i r(:ll(is irr,,l t|r,ll-r|isll('t.:; li, {)- {ltc tttt l)tr'r'r,rr.,'1.\llr.rrtotrtr. ('('crl(i(l illtll lile lo ;r positiort irt ll\)nl {}l (lartlitral. .\l i!rt.srrrrrr. llil(' ll)(.[)rr1tr] lrrs llr thc colrrll'itl pr.o(,r.,$sionto an(l llrc rrlrcle carlt rrainr'tiIlrc ll,rsl Iilr. .lolur[ilol. \\ ab 1rt,lrrilr;rll,r. inl trtrltrt'Ct[ lr!' 'i It'ottt tltc t'cliqiort-s (](!t.c1l{}11.11,(rrc I ili'lli(.rl\ ;iiilat llisliuli uf ('i{ili ililr!(!- l {}t r.ai.!r. ltc httrl a nlr.ttt Liislrop l,co lltrr.r;lcy. r11rl,\.,' ilr:rr,. pf lt .ci;rrrrl. t{) l)t. ,------ of lrt. qrr'r,lirr:1;lrrl ! 'VOL. :r lrarrrlslurlic lnd firr '\rriibrslrrrI 'l'ltis \1'tlrrr'.Sorirrr l}:rrrl: Ilirlir,ir,,\ir. iirr. -

John Mcshain Photographs 1990.268

John McShain photographs 1990.268 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on September 14, 2021. English Describing Archives: A Content Standard Audiovisual Collections PO Box 3630 Wilmington, Delaware 19807 [email protected] URL: http://www.hagley.org/library John McShain photographs 1990.268 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical Note .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 6 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 6 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 7 Personal photographs ................................................................................................................................... 7 Early photographs .................................................................................................................................... -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions Of

March 6, 1996 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð Extensions of Remarks E 281 those who stayed home, for sound and con- COMMEMORATING BLACK HISTORY morrow'' I would like to pay tribute to an out- venient reasons, of course. MONTH standing St. Louisan who exemplifies the high- But the greatest lesson I have learned, the est values and qualities of leadership in the most important of my education, is really SPEECH OF African-American community, Mrs. Margaret the essential imperative of this century. It is called leadership. We brandish the word. We HON. NANCY PELOSI Bush Wilson. Mrs. Wilson is a St. Louis native who grad- admire its light. But we seldom define it. OF CALIFORNIA uated from Sumner High School and received Outside Caen in the Normandy countryside IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES of France is a little cemetery. Atop one of a B.A. degree in economics, cum laude, from the graves is a cross on which is etched these Wednesday, February 28, 1996 Talladega College. She went on to earn her words: ``Leadership is wisdom and courage Ms. PELOSI. Mr. Speaker, I thank my distin- LL.B from Lincoln University School of Law. and a great carelessness of self.'' Which guished colleagues, Congressmen STOKES Mrs. Wilson has been a highly respected jurist means, of course, that leaders must from and PAYNE, for calling this special order in in St. Louis for many years and is admitted to time to time put to hazard their own politi- celebration of Black History Month for choos- practice before the U.S. Supreme Court. -

"VOICJE SEPTEMBER 12, 1975 25C VOL

"VOICJE SEPTEMBER 12, 1975 25c VOL. XVII N0.27 •fc THIS SUNDAY 1st U.S. native to be canonized VATICAN CITY — (NC) — The 15,000 American ticketholders to Mother Elizabeth Seton's canonization Sept. 14 found a special edition of the Vatican newspaper L'Osservatore Romano devoted principally to her, as the first native-born citizen of the United States to be declared a saint. The front page of L'Osservatore Romano's weekly English edition featured a photo of the new saint, a five-day schedule of events and ceremonies, and an account of the canonization itself. A biography of her filled the centerfold. FATHER LAMBERT GREENAN, the Irish Dominican who edits the worldwide English-language weekly, observed: "While it Masses to mark Canonization Many churches throughout the Archdiocese of Miami will observe the canonization of Mother Elizabeth Ann Seton this Sunday. Special Pontifical Mass honoring the first U.S. born saint will be celebrated by Archbishop Coleman F. Carroll at 11 a.m. Sunday Sept. 14, in the Cathedral of St. Mary, 7525 N.W. 2nd. Avenue. is true that Mother Seton's canonization is of greatest interest in America, it is important to the English-speaking world at large." Reserved sections in St. Peter's Square for the 9:30 a.m. ceremonies on Sunday Sept. 14, were set aside for ticketholders, mainly American. The rest of the huge square was left for the St. Elizabeth Seton, the first U.S.-born saint, is depicted by Sister Laura Bench of Seton Hill College. throngs of Romans, the hundreds of pilgrims from the north Italian The canonization will take place Sunday, Sept. -

Catholic Flashback: Remembering the 1978 Election of Pope St. John Paul II

Catholic Flashback: Remembering the 1978 election of Pope St. John Paul II October 16, 1978: The first balcony appearance of newly-elected Pope John Paul II (CNS File Photo) Where were you on October 16, 1978? I was between classes at college in Philadelphia when word came through the hallways that white smoke had been seen coming from the chimney of the Sistine Chapel. After three days of waiting, we finally had a new pope! I rushed to turn on my tiny black and white TV, and watched as the crowds grew in St. Peter’s Square while commentators speculated as to which Italian cardinal might become the 264th leader of the Roman Catholic Church. I will never forget the announcement in Latin that Cardinal Karol Jozef Wojtyla (1920-2005), at age 58, had been elected as the 263rd successor of St. Peter the Apostle. The news commentators were struggling to figure out who he was, from which country he came, and how to pronounce his name. You see, Pope John Paul II was the first non-Italian pope in 455 years. Those reporting on the conclave from both the Catholic and secular press were all assuming that this new pontiff would also be Italian. Instead, the College of Cardinals elected the Archbishop of Krakow, Poland, who had served in that position since 1963 and who was named a cardinal by Pope Paul VI in 1967. Ten interesting facts about the election of Pope John Paul II: 1. The Year of Three Popes: This was the second time in less than eight weeks that Catholics from around the world gathered in front of our televisions to learn the outcome of a papal election. -

Cathedral Alumni News Spring – Summer 2012

Cathedral Alumni News Spring – Summer 2012 SAVE THE DATE: 20TH ANNUAL CATHEDRAL PREP GOLF CLASSIC NORTH HILLS COUNTRY CLUB THURSDAY, OCTOBER 4, 2012 On Thursday, October 4, 2012, at the North Hills Country Club, Manhasset, New York, Cathedral Prep’s Alumni Association will host its Twentieth Annual Golf Classic benefitting the students of Cathedral Prep. As always, it should be a wonderful day! Since its inception in 1992, we have always had great weather, great food, great fun and great friends. There will be great golfing, raffles, auctions, a fantastic spread for breakfast, a hotdog lunch, a gourmet cocktail hour and most importantly, the opportunity to help Cathedral Prep to continue its mission of education and priestly vocation discernment. Billy Oettinger, ’80, and Jim Farmer, ’80, will be serving as this year’s chairmen. At this year’s outing, we will recognize the The Friel brothers and Ray Nash from last year’s Golf outstanding commitment of the Friel Brothers to Cathedral Prep Classic. with the Cooperatores in Veritatis Award (named in honor of Pope Benedict XVI): Bernie, ’72; Dan, ’73; Connell, ’77; Peter, ’78; Kevin, ’81; and Paul, ’85. Remember to register as soon as possible as we always fill up! Check in time will be at 10:00 AM with brunch following. The shotgun start will begin at 12:00 PM. There will be lunch and refreshments served at the front and back 9s and at the clubhouse. Contests include: hole-in-one for a 2013 car, longest drive, and closest to the pin. We will also be holding a silent auction, a public auction and the annual Blue & White Raffle drawing for two (2) cash prizes of $2,000.00. -

Cultivate the Attitude of the Magi Says Bishop at Epiphany Mass

50¢ January 15, 2012 Volume 86, No. 2 GO DIGITAL todayscatholicnews.org todayscatholicnews.org Serving the Diocese of Fort Wayne-South Bend CLICK ON CIRCULATION Cardinals announced ’’ Archbishops Dolan TTODAYODAYSS CCATHOLICATHOLIC and O’Brien named Pages 1, 4, 5 Cultivate the attitude of the Magi Men’s conference Franciscan Father says bishop at Epiphany Mass David Mary Engo to speak Page 3 BY LISA KOCHANOWSKI SOUTH BEND — Three Wise Men from the east followed a star to the newborn King of the Jews SANKOFA long ago with the words, “we have come to wor- ship Him,” as their reason for traveling such a long Black Catholic conference distance. These words are what Bishop Kevin C. Rhoades challenged the congregation of St. Matthew in South Bend Cathedral to think about in their daily life at the Jan. Pages 3, 8 8 Epiphany Mass. Bishop Rhoades celebrated the Solemnity of the Epiphany of the Lord with the parish community at 11 a.m. Mass. He entered the celebration with the three wise men, followed by a fanfare of trumpets, Right-to-work music and the scent of incense filling the air. “A blessed Epiphany to all,” proclaimed Bishop Indiana legislature resumes Rhoades to the congregation at the beginning of Page 10 Mass. He told the crowd that his visit to St. Matthew Cathedral was extra special with a unique gift of a crosier presented to him by Msgr. Michael Heintz. One side of the crozier has an image of St. Matthew and the other side has an image of the diocesan coat Erlandson receives post of arms. -

Congressional Record—House H3640

H3640 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð HOUSE April 18, 1996 they care about our community and No task is too big. No challenge is looking to repeal the New Deal, but care deeply about helping others. too great. These dedicated young peo- much of the Great Society simply did These heros reach out and lend a ple are faced with amazing challenges not work. Not all of it, but a good part helping hand to at-risk schoolchildren. but they never give up. of it. Motivate Our MindsÐMOM's for A special gift that these young men I was coming to Washington this shortÐis a very special organization in and women have received, is something week, I noticed on my calendar, I have my hometown of Muncie. that I, too, learned at an early age: quotes on my calendar. This one hap- Mr. wife, Ruthie, visited the MOM's ``Always do your best, hard work will pened to have been from Ann Landers. program just a few weeks ago. She be rewarded and never, never give in.'' I think it defines something that is ab- shared with me the love and friendship Mr. Speaker, the volunteers and espe- solutely essential. It says, ``In the final the volunteers at the MOM program cially the children involved with the analysis, it is not what you do for your give to inner city schoolchildren. MOM program in Muncie, Indiana are children, but what you have taught MOM's first started in 1987, when two Hoosier heroes. That is my report from them to do for themselves that will women, Mary Dollison and Raushanah Indiana. -

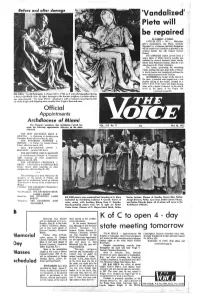

Pieta Will Be Repaired K of C to Open 4

Before and after damage 'Vandalized' Pieta will be repaired By JAMES C. O'NEILL VATICAN CITY - (NC) - Michelan- gelo's masterpiece, the Pieta, severely damaged by a hammer-wielding Hungarian will be restored as faithfully as possible to its original beauty but will remain forever flawed. The 6,700-pound statue carved from a single block of white Cararra marble was smashed by several hammer blows shortly before noon Pentecost Sunday, May 20, in its side chapel in St. Peter's Basilica. The statue, portraying the sorrowing Virgin holding the limp, dead body of Christ, is world famous and considered perhaps the most valued treasure of the Vatican. ACCORDING to visitors in the church at the time, a bearded man leaped over a low marble railing of the chapel, jumped on a table in front of the statue and began flailing away with a mason's hammer. In the rain of blows on the figure, of the Virgin the (continued on page 21) CHE PIETA," by Michelangelo, is shown left in 1964 as it was photographed during »e New York World's Fair. At right, damage to the fqmous sculpture is evident after a tan, who shouted, "I'm Jesus Christ," attacked it with a hammer severing the left rm of the Virgin and chipping some marble from Virgin's face and nose. Official ••• Appointments Archdiocese of Miami The Chancery announces that Archbishop Carroll has VOL. XIV No. 11 May 26, 1972 made the following appointments effective on the dates indicated. *•/ *! T ' . ' • THE MOST REVEREND RENE H. j ; GRACIDA — to Chairman of Arehdiocesan £.