EC I963 the AFRICAN COMMUNIST This Journal Is Published

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

And Others a Geographical Biblio

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 052 108 SO 001 480 AUTHOR Lewtbwaite, Gordon R.; And Others TITLE A Geographical Bibliography for hmerican College Libraries. A Revision of a Basic Geographical Library: A Selected and Annotated Book List for American Colleges. INSTITUTION Association of American Geographers, Washington, D.C. Commission on College Geography. SPONS AGENCY National Science Foundation, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 70 NOTE 225p. AVAILABLE FROM Commission on College Geography, Arizona State University, Tempe, Arizona 85281 (Paperback, $1.00) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.65 BC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Annotated Bibliographies, Booklists, College Libraries, *Geography, Hi7her Education, Instructional Materials, *Library Collections, Resource Materials ABSTRACT This annotated bibliography, revised from "A Basic Geographical Library", presents a list of books selected as a core for the geography collection of an American undergraduate college library. Entries numbering 1,760 are limited to published books and serials; individual articles, maps, and pamphlets have been omii_ted. Books of recent date in English are favored, although older books and books in foreign languages have been included where their subject or quality seemed needed. Contents of the bibliography are arranged into four principal parts: 1) General Aids and Sources; 2)History, Philosophy, and Methods; 3)Works Grouped by Topic; and, 4)Works Grouped by Region. Each part is subdivided into sections in this general order: Bibliographies, Serials, Atlases, General, Special Subjects, and Regions. Books are arranged alphabetically by author with some cross-listings given; items for the introductory level are designated. In the introduction, information on entry format and abbreviations is given; an index is appended. -

Discover Ltd / Education for All Morocco Y6 – Y7 Geography Transition Unit

Discover Ltd / Education for All Morocco Y6 – Y7 Geography Transition Unit For Primary School Leaders and Teachers June 2020 Dear Colleague I am delighted to attach a copy of the Y6-7 Geography Transition Unit. This unit of work has been designed to address the needs of Year 6 pupils in primary schools as they prepare for their transition into Year 7 at their secondary school. It has been prepared now (May 2020) in an attempt to address any uncertainty around school openings and traditional transition arrangements. We at Discover Ltd and Education for All Morocco decided to use the wealth of resources we have collected over many years for a variety of audiences to prepare a unit of home or school-based study around the ‘geography’ of Morocco. Our intention is that this supports: a) primary school colleagues planning home learning units; b) provides Year 6 pupils with a high quality study pack which aims to develop and enhance their knowledge, skills and understanding across the 3 key aims of the NC for Geography (skills; places / context; and physical / human geography); and c) supports secondary school colleagues as you revise and modify your traditional transition arrangements this term, should you not be able to hold face-to-face sessions with your new Year 7 intake of students. The aim is then that the pupils in Year 6 would bring their ‘completed’ study pack with them at the start of Year 7 to share with their geography teacher. We fully recognise that this is but a tiny part of the primary-secondary transition process but we hope that it makes that step from Y6-Y7 that little bit easier and slightly less stressful for Y6 pupils’. -

Expat Guide to Casablanca

EXPAT GUIDE TO CASABLANCA SEPTEMBER 2020 SUMMARY INTRODUCTION TO THE KINGDOM OF MOROCCO 7 ENTRY, STAY AND RESIDENCE IN MOROCCO 13 LIVING IN CASABLANCA 19 CASABLANCA NEIGHBOURHOODS 20 RENTING YOUR PLACE 24 GENERAL SERVICES 25 PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION 26 STUDYING IN CASABLANCA 28 EXPAT COMMUNITIES 30 GROCERIES AND FOOD SUPPLIES 31 SHOPPING IN CASABLANCA 32 LEISURE AND WELL-BEING 34 AMUSEMENT PARKS 36 SPORT IN CASABLANCA 37 BEAUTY SALONS AND SPA 38 NIGHT LIFE, RESTAURANTS AND CAFÉS 39 ART, CINEMAS AND THATERS 40 MEDICAL TREATMENT 45 GENERAL MEDICAL NEEDS 46 MEDICAL EMERGENCY 46 PHARMACIES 46 DRIVING IN CASABLANCA 48 DRIVING LICENSE 48 CAR YOU BROUGHT FROM ABROAD 50 DRIVING LAW HIGHLIGHTS 51 CASABLANCA FINANCE CITY 53 WORKING IN CASABLANCA 59 LOCAL BANK ACCOUNTS 65 MOVING TO/WITHIN CASABLANCA 69 TRAVEL WITHIN MOROCCO 75 6 7 INTRODUCTION TO THE KINGDOM OF MOROCCO INTRODUCTION TO THE KINGDOM OF MOROCCO TO INTRODUCTION 8 9 THE KINGDOM MOROCCO Morocco is one of the oldest states in the world, dating back to the 8th RELIGION AND LANGUAGE century; The Arabs called Morocco Al-Maghreb because of its location in the Islam is the religion of the State with more than far west of the Arab world, in Africa; Al-Maghreb Al-Akssa means the Farthest 99% being Muslims. There are also Christian and west. Jewish minorities who are well integrated. Under The word “Morocco” derives from the Berber “Amerruk/Amurakuc” which is its constitution, Morocco guarantees freedom of the original name of “Marrakech”. Amerruk or Amurakuc means the land of relegion. God or sacred land in Berber. -

Greater Ouarzazate, a 21St-Century Oasis City : Historical Benchmarks and International Visibility

GREATER OUARZAZATE, A 21ST-CENTURY OASIS CITY : HISTORICAL BENCHMARKS AND INTERNATIONAL VISIBILITY CONTEXT DOCUMENT INTERNATIONAL WORKSHOP OF URBAN PLANNING OUARZAZATE - MOROCCO - 3RD - 16TH NOVEMBER 2018 CONTENTS 1. Contextual Framework . .7 1. Presentation of Morocco: population, climate, diversity ........................ 7 1.1. General description of Morocco �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������7 1.2. Toponymy �����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������7 1.3. Geography of Morocco ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������7 1.4. Plains . .8 1.5. Coatline . .8 1.6. Climate in Morocco ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������9 1.7. Morocco’s hydrography . .9 2. Territorial organization in Morocco ........................................ 10 3. Morocco’s international positioning ........................................ 11 4. Physical and environnemental setting, and geographic location ................. 12 4.1. Geographic location of the workshop’s perimeter . .12 4.2. Physical data of the Great Ouarzazate: �����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������13 5. Histroy of the given territoiry ............................................. 14 6. Political and -

Geography Course Number and Title: GR 100 Introduction to Geography Division: Lower Faculty Name: M

SEMESTER AT SEA COURSE SYLLABUS Colorado State University, Academic Partner Voyage: Spring 2019 Discipline: Geography Course Number and Title: GR 100 Introduction to Geography Division: Lower Faculty Name: M. Troy Burnett Semester Credit Hours: 3 Prerequisites: None COURSE DESCRIPTION In this course, students will be introduced to the multidisciplinary field of Geography—a discipline that straddles natural and social sciences as well as humanities. Topics in physical geography include weather/climate, biogeography, and geomorphology; while topics in human geography include cultural, economic, political and urban studies. As a survey course, the primary objective is to offer students insight into the conceptual terms and perspectives used in geography and how these are deployed in the field and for research. Space, place, global, local, scale, culture, nature, identity and image are but few of these terms to be introduced. These will be placed in the context of societal and environmental processes that equip the student to understand and come to terms with observable phenomena in different locations on the Earth. Throughout the course, some key tools of geographical analysis will be introduced and through fieldwork students will be required to demonstrate skills in using the introduced concepts and tools. LEARNING OBJECTIVES Understand the breadth of the discipline of geography. Be able to describe the differences and complementarities of human and physical geography Recognize the interconnectedness of people, places, and environment. Learn about the tools that geographers use. Develop map-reading skills Perceive the role that geography plays in our day‐to‐day lives. REQUIRED TEXTBOOKS Author: A. Getis, M. Bjelland, and V. -

Morocco and Senegal: Faces of Islam in Africa

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 443 756 SO 031 723 TITLE Morocco and Senegal: Faces of Islam in Africa. Fulbright-Hays Summer Seminars Abroad, 1999 (Morocco and Senegal). INSTITUTION Center for International Education (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 1999-00-00 NOTE 259p. PUB TYPE Collected Works General (020)-- Guides Classroom - Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC11 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Area Studies; Developing Nations; Elementary Secondary Education; Fine Arts; Foreign Countries; *Global Education; Higher Education; Islamic Culture; *Muslims; *Non Western Civilization; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Fulbright Hays Seminars Abroad Program; *Morocco; *Senegal ABSTRACT These projects were completed by participants in the Fulbright-Hays summer seminar in Morocco and Senegal in 1999. The participants represented various regions of the United States and different grade levels and subject areas. The 13 curriculum projects in the collection are: (1) "Doorway to Morocco: A Student Guide" (Sue Robertson); (2) "A Social Psychological Exploration of Islam in Morocco and Senegal" (Laura Sidorowicz); (3) "An Exhibition of the Arts of Morocco and Senegal" (Nancy Webber); (4) "Morocco: Changing Times?" (Patricia Campbell); (5) "The Old Town and Your Town" (Amanda McClure);(6) "Everyday Life in Morocco and Senegal: A Lesson Plan" (Nancy Sinclair); (7) "French Colonial Regimes and Sufism in Morocco and Senegal: A Lesson Plan" (Arthur Samuels); (8) "Language, Education, and Literacy in Morocco" (Martha Grant); (9) "Integrating Islam in an Introductory Course in Social Psychology" (Kellina Craig);(10) "Lesson Plans for High School Art Classes" (Tewodross Melchishua); (11) "A Document-Based Question Activity Project: The Many Faces of Islam" (Richard Poplaski); (12) "Slide Presentations" (Susan Hult); and (13) "A Curriculum Guide for 'Year of the Elephant' by Leila Abouzeid" (Ann Lew). -

The Atlas Mountains. and at 5.30 A.M

96 The Atlas Mountains. and at 5.30 A.M. we were on the lower edge of the crater, a keen N. wind, temperature 15° (F.), a slight sulphur smell in the air, and an absolutely perfect view. McAllister had never been beyond this point, much to our surprise, but we were all soon on our way round the E. side of the crater to the summit. From 7 A.M. till nearly 9 we stayed on the bare summit, the sun warm and the air almost motionless. Orizaba, Malinche, Ixtaccihuatl, Nevado de Toluca, and, we thought, the very distant Sierra Madre del Sur, all stood out clearly, as well as Mexico City and Amecameca to the N. and Puebla to the S. The crater was roaring steam from several vents it has since been in mild eruption. Returning to camp at aboD:t 11.30 we were waited upon by a dozen or so doubtful-looking characters, all armed, who said they wanted our money but had to be .content with cigarettes. After a horribly dusty ride of 4 hours to Amecameca we were lucky in securing a car to get us back to Mexico City in time for dinner. [For notes and various ascents of these two peaks, see 'A.J.' 4, 234-7 ; 8, 280-1 ; 14, 403-4; 15, 268-72 (with illustrations); 18, 456-61 (includes also the ascent of 0RIZABA) ; 21, 144-5.] THE ATLAS MouNTAINS. • BY ANDREA DE POLLITZER-POLLENGHI. GENERAL. N the 'litus importuosu~' of the ancient geographers, that coast beaten ceaselessly by the violence of the Atlantic and stormed by the incfemency of the Mediterranean, the Phrenicians and Oarthaginians first landed. -

Destiny Worse Than Artificial Borders in Africa: Somali Elite Politics1

Destiny Worse than Artificial Borders in Africa: Somali Elite Politics1 Abdi Ismail Samatar I. Introduction Much political and scholarly energy has been spent in understanding the nature and impacts of political boundaries on African development and public life. The standard argument by many anticolonial groups is that the Berlin Conference that instigated the European scramble for Africa in the 19th century paid no attention to the geography of Afri- can livelihood experiences.2 Drawing boundaries engulfing territories claimed by various Europeans was arbitrary, and the legacy of their existence has caused much grief in the continent.3 It is a fact that colo- nial boundaries in Africa were artificial, but it is also the case that all political boundaries nearly everywhere are not natural. Most of these studies underscore how artificial colonial borders seg- mented communities that shared economic, ecological and cultural resources. In some cases, these boundaries have been the “cause” of inter-state conflicts between post-colonial countries, i.e., Ethiopia and Eritrea, Ethiopia and Somalia; Kenya and Somalia; Algeria and Morocco; Libya and Chad. But other equally artificial borders in the continent have not incited similar conflagrations despite fragmenting cultural, religious and ethnic groups, such as the Massai of Kenya and Tanzania, and the many communities that straddle along the borders of South Africa, Botswana, Zimbabwe, and Namibia, etc. An unexplored question that demands urgent attention is why conflicts develop over some borders and not over others in different parts of the continent.4 As important as this question is, this paper examines a related but 19 Bildhaan Vol. -

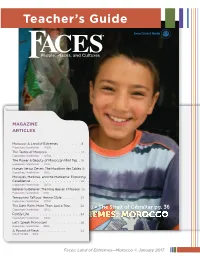

Land of Extremes—Morocco © January 2017 Contents

Teacher’s Guide People, Places, and Cultures MAGAZINE ARTICLES Morocco: A Land of Extremes 8 Expository Nonfiction 1200L The Tastes of Morocco 12 Expository Nonfiction 1050L The Power & Beauty of Moroccan Mint Tea 16 Expository Nonfiction 1150L Human Versus Desert: The Marathon des Sables 18 Expository Nonfiction 1120L Mosques, Medinas, and the Mahkama: Exploring Casablanca 22 Expository Nonfiction 1260L Believer to Believer: The King Hassan II Mosque 26 Expository Nonfiction 1170L Temporary Tattoos: Henna-Style 29 Expository Nonfiction 1070L The Date Palm: More Than Just a Tree 30 Expository NonfictionBeliever 1210L to Believer pg. 26 • The Strait of Gibraltar pg. 36 Family Life 34 Expository NonfictionLAND 1130L OF EXTREMES: MOROCCO Let’s Speak Moroccan! 38 Expository Nonfiction 880L A Pound of Flesh 42 Play/Folktale 930L Faces: Land of Extremes—Morocco © January 2017 Contents Teacher’s Guide for Faces: OVERVIEW People, Places, and Cultures Land of Extremes—Morocco In this magazine, readers will learn how physical Using This Guide 2 and human characteristics Skills and Standards Overview 3 have shaped Believer to Believer pg. 26 • The Strait of Gibraltar pg. 36 LAND OF EXTREMES: MOROCCO Moroccan culture. Faces: Land Article Guides 4 of Extremes— Morocco includes information about Morocco’s physical geography, natural and Cross-Text Connections 15 man-made resources, and religion, as well as the people who live there. Mini-Unit 16 Graphic Organizers 19 Appendix: Meeting State and National Standards 21 ESSENTIAL QUESTION: How have physical -

The Regional Discourse of French Geography in the Context of Indochina: the Theses of Charles Robequain and Pierre Gourou Dany Bréelle

The Regional Discourse of French Geography in the Context of Indochina: The Theses of Charles Robequain and Pierre Gourou Dany Bréelle To cite this version: Dany Bréelle. The Regional Discourse of French Geography in the Context of Indochina: The Theses of Charles Robequain and Pierre Gourou. Geography. Flinders University, 2003. English. tel-00363032 HAL Id: tel-00363032 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00363032 Submitted on 20 Feb 2009 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The Regional Discourse of French Geography in the Context of Indochina: The Theses of Charles Robequain and Pierre Gourou By Dany Michelle Bréelle PhD Thesis Flinders University of South Australia School of Geography, Population and Environmental Management September 2002 Table of Contents Abstract........................................................................................................................................................................................... vi Thesis Declaration........................................................................................................................................................................vii -

S T U D I M a G E B

UNIOR D.A.A.M. Centro di Studi Mag·rebini REBINI ‚ STUDI MAG STUDI Emerging Actors in Post-Revolutionary North Africa Actors in Post-Revolutionary North Emerging Berber Movements: Identity, New Issues and Challenges Berber Movements: Identity, Nuova Serie Vol. XIV - XV Tomo II Napoli 2016 - 2017 UNIOR D.A.A.M. Centro di Studi Mag·rebini UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI NAPOLI “L’ORIENTALE” DIPARTIMENTO ASIA, AFRICA E MEDITERRANEO Centro di Studi Magrebini· STUDI MAG‚REBINI Nuova Serie Volumi XIV - XV Napoli 2016 - 2017 REBINI ‚ EMERGING ACTORS IN POST-REVOLUTIONARY NORTH AFRICA Berber Movements: Identity, New Issues and New Challenges Preface by STUDI MAG STUDI Federico CRESTI Edited by Anna Maria DI TOLLA & Ersilia FRANCESCA Nuova Serie Vol. XIV - XV Tomo II Tomo II ISSN: 0585-4954 Napoli ISBN: 978-88-6719-156-7 2016 - 2017 UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI NAPOLI “L’ORIENTALE” DIPARTIMENTO ASIA, AFRICA E MEDITERRANEO Centro di Studi Magrebini· STUDI MAGREBINI‚ Nuova Serie Volumi XIV - XV Napoli 2016 - 2017 EMERGING ACTORS IN POST-REVOLUTIONARY NORTH AFRICA Berber Movements: Identity, New Issues and New Challenges Preface by Federico CRESTI Edited by Anna Maria DI TOLLA & Ersilia FRANCESCA Tomo II UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI NAPOLI “L’ORIENTALE” DIPARTIMENTO ASIA, AFRICA E MEDITERRANEO CENTRO DI STUDI MAG‚REBINI Presidente: Sergio BALDI Direttore della rivista: Agostino CILARDO &RQVLJOLR6FLHQWLÀFR6HUJLR%$/',$QQD0DULD',72//$0RKD ENNAJ, Ersilia FRANCESCA, Ahmed HABOUSS, El Houssain EL MOUJAHID, Abdallah EL MOUNTASSIR, Ouahmi OULD- BRAHAM, Nina PAWLAK, Fatima SADIQI Consiglio Editoriale: Flavia AIELLO, Orianna CAPEZIO, Carlo DE ANGELO, Roberta DENARO Piazza S. Domenico Maggiore , 12 Palazzo Corigliano 80134 NAPOLI Direttore Responsabile: Agostino Cilardo Autorizzazione del Tribunale di Napoli n. -

Sufism and Hagiography in Moroccan Context

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Female religious agents in Morocco: Old practices and new perspectives Ouguir, A. Publication date 2013 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Ouguir, A. (2013). Female religious agents in Morocco: Old practices and new perspectives. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:29 Sep 2021 Chapter Three: Sufism and Hagiography in Moroccan Context To further contextualize Moroccan female sainthood, this chapter focuses on Moroccan Sufism and hagiography. Its first section goes into Moroccan culture and identity, discussing Moroccan Islam in relation to Moroccan geography and history. The second section deals with Moroccan Sufism and the way it is approached by different scholars. The final section focuses on the genre of hagiography amidst other genres, and on the characteristics of Moroccan hagiography in particular.