Recent Dvaravati Discoveries, and Some Khmer Comparisons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Helminthic Infections of Pregnant Women in Maha Sarakham Province, Thailand

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Mitteilungen der Österreichischen Gesellschaft für Tropenmedizin und Parasitologie Jahr/Year: 1993 Band/Volume: 15 Autor(en)/Author(s): Saowakontha S., Hinz Erhard, Pipitgool V., Schelp F. P. Artikel/Article: Helminthic Infections of Pregnant Women in Maha Sarakham Province, Thailand. 171-178 ©Österr. Ges. f. Tropenmedizin u. Parasitologie, download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Mitt. Österr. Ges. Faculty of Associated Medical Sciences (Dean: Dr. Sastri Saowakontha), Tropenmed. Parasitol. 15 (1993) Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen, Thailand (1) 171 - 178 Department of Parasitology (Head: Prof. Dr. E. Hinz), Institute of Hygiene (Director: Prof. Dr. H.-G. Sonntag), University of Heidelberg, Germany (2) Department of Parasitology (Head: Assoc. Prof. Vichit Pipitgool), Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen, Thailand (3) Department of Epidemiology (Head: Prof. Dr. F. P. Schelp), Institute of Social Medicine, Free University, Berlin, Germany (4) Helminthic Infections of Pregnant Women in Maha Sarakham Province, Thailand S. Saowakontha1, E. Hinz2, V. Pipitgool3, F. P. Schelp4 Introduction Infections and nutritional deficiencies are well known high risk factors especially in pregnant and lactating women: "Pregnancy alters susceptibility to infection and risk of disease which can lead to deterioration in maternal health" and "infections during pregnancy frequently influence the outcome of pregnancy" (1). This is true primarily of viral, bacterial and protozoal infections. With regard to human helminthiases, knowledge is less common as interactions between helminthiases and pregnancy have mainly been studied only in experimentally in- fected animals. Such experiments have shown that pregnant animals and their offspring are more susceptible to infections with certain helminth species if compared with control groups. -

A Model for the Management of Cultural Tourism at Temples in Bangkok, Thailand

Asian Culture and History; Vol. 6, No. 2; 2014 ISSN 1916-9655 E-ISSN 1916-9663 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education A Model for the Management of Cultural Tourism at Temples in Bangkok, Thailand Phra Thanuthat Nasing1, Chamnan Rodhetbhai1 & Ying Keeratiburana1 1 The Faculty of Cultural Science, Mahasarakham University, Khamriang Sub-District, Kantarawichai District, Maha Sarakham Province, Thailand Correspondence: Phra Thanuthat Nasing, The Faculty of Cultural Science, Mahasarakham University, Khamriang Sub-District, Kantarawichai District, Maha Sarakham Province 44150, Thailand. E-mail: [email protected] Received: May 20, 2014 Accepted: June 12, 2014 Online Published: June 26, 2014 doi:10.5539/ach.v6n2p242 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ach.v6n2p242 Abstract This qualitative investigation aims to identify problems with cultural tourism in nine Thai temples and develop a model for improved tourism management. Data was collected by document research, observation, interview and focus group discussion. Results show that temples suffer from a lack of maintenance, poor service, inadequate tourist facilities, minimal community participation and inefficient public relations. A management model to combat these problems was designed by parties from each temple at a workshop. The model provides an eight-part strategy to increase the tourism potential of temples in Bangkok: temple site, safety, conveniences, attractions, services, public relations, cultural tourism and management. Keywords: management, cultural tourism, temples, Thailand, development 1. Introduction When Chao Phraya Chakri deposed King Taksin of the Thonburi Kingdom in 1982, he relocated the Siamese capital city to Bangkok and revived society under the name of his new Rattanakosin Kingdom (Prathepweti, 1995). Although royal monasteries had been commissioned much earlier in Thai history, there was a particular interest in their restoration during the reign of the Rattanakosin monarchs. -

THE ROUGH GUIDE to Bangkok BANGKOK

ROUGH GUIDES THE ROUGH GUIDE to Bangkok BANGKOK N I H T O DUSIT AY EXP Y THANON L RE O SSWA H PHR 5 A H A PINKL P Y N A PRESSW O O N A EX H T Thonburi Democracy Station Monument 2 THAN BANGLAMPHU ON PHE 1 TC BAMRUNG MU HABURI C ANG h AI H 4 a T o HANO CHAROEN KRUNG N RA (N Hualamphong MA I EW RAYAT P R YA OAD) Station T h PAHURAT OW HANON A PL r RA OENCHI THA a T T SU 3 SIAM NON NON PH KH y a SQUARE U CHINATOWN C M HA H VIT R T i v A E e R r X O P E N R 6 K E R U S N S G THAN DOWNTOWN W A ( ON RAMABANGKOK IV N Y E W M R LO O N SI A ANO D TH ) 0 1 km TAKSIN BRI DGE 1 Ratanakosin 3 Chinatown and Pahurat 5 Dusit 2 Banglamphu and the 4 Thonburi 6 Downtown Bangkok Democracy Monument area About this book Rough Guides are designed to be good to read and easy to use. The book is divided into the following sections and you should be able to find whatever you need in one of them. The colour section is designed to give you a feel for Bangkok, suggesting when to go and what not to miss, and includes a full list of contents. Then comes basics, for pre-departure information and other practicalities. The city chapters cover each area of Bangkok in depth, giving comprehensive accounts of all the attractions plus excursions further afield, while the listings section gives you the lowdown on accommodation, eating, shopping and more. -

Murals in Buddhist Buildings: Content and Role in the Daily Lives of Isan People

Asian Culture and History; Vol. 6, No. 2; 2014 ISSN 1916-9655 E-ISSN 1916-9663 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Murals in Buddhist Buildings: Content and Role in the Daily Lives of Isan People Thawat Trachoo1, Sastra Laoakka1 & Sisikka Wannajun1 1 The Faculty of Cultural Science, Mahasarakham University, Khamriang Sub-District, Kantarawichai District, Maha Sarakham Province, Thailand Correspondence: Thawat Trachoo, The Faculty of Cultural Science, Mahasarakham University, Khamriang Sub-District, Kantarawichai District, Maha Sarakham Province 44150, Thailand. E-mail: [email protected] Received: May 14, 2014 Accepted: June 6, 2014 Online Published: June 12, 2014 doi:10.5539/ach.v6n2p184 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ach.v6n2p184 Abstract This is a qualitative research aimed at assessing the current state of Buddhist murals in Northeastern Thailand, the elements of society they reflect and their role in everyday life. The research area for this investigation is Northeastern Thailand, colloquially known as Isan. Three ethnic communities were purposively selected to comprise the research populations. These were the Tai Korat of Nakhon Ratchasima Province, Tai Khmer of Buriram Province and Tai Lao of Ubon Ratchatani Province. Data collection tools were basic survey, participant and non-participant observation, structured and non-structured interview, focus group discussion and workshop. Results show that there are two major groups of Buddhist temple murals in Isan: those depicting ancient culture and customs painted prior to 1957 and contemporary murals painted after 1957. For the most part, murals are found on the walls of the ubosot and the instruction halls of the temples. The objectives of mural paintings were to worship the lord Buddha, decorate the temples, provide education to community members and maintain historical records. -

Burmese Migrant Workers: Dimensions of Cultural Adaptation and an Assimilation Model for Economic and Social Development in the Central Coastal Region of Thailand

Asian Culture and History; Vol. 7, No. 1; 2015 ISSN 1916-9655 E-ISSN 1916-9663 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Burmese Migrant Workers: Dimensions of Cultural Adaptation and an Assimilation Model for Economic and Social Development in the Central Coastal Region of Thailand Kamonchat Pathumsri1, Boonsom Yodmalee1 & Kosit Phaengsoi1 1 The Faculty of Cultural Science, Mahasarakham University, Khamriang Sub-District, Kantarawichai District, Maha Sarakham Province, Thailand Correspondence: Kamonchat Pathumsri, The Faculty of Cultural Science, Mahasarakham University, Khamriang Sub-District, Kantarawichai District, Maha Sarakham Province 44150, Thailand. E-mail: [email protected] Received: July 7, 2014 Accepted: July 15, 2014 Online Published: September 22, 2014 doi:10.5539/ach.v7n1p35 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ach.v7n1p35 Abstract This research is aimed at studying the background of Burmese migrant labor, the current state and problems with Burmese migrant labor and the dimensions of cultural adaptation and an assimilation model for economic and social development of Burmese migrant labor in the Central Coastal Region of Thailand. This is a qualitative study carried out between November 2012 and November 2013 that incorporates document study and field research. The research area was purposively selected as Samut Sakhon, Samut Prakan and Samut Songkhram Provinces. The research sample was also purposively selected and comprised of 150 individuals, divided into three groups: key informants (n=21), casual informants (n=69) and general informants (n=60). Tools used for data collection were observation, interview and focus group discussion. Data was validated using a triangulation technique. The result of the investigation is a development model in five sections: cost of labor, work conditions, job security, career progression and work sanitation and safety. -

Evaluation of Yield Components on Capsicum Spp. Under Two Production Systems

Journal of Advanced Agricultural Technologies Vol. 4, No. 1, March 2017 Evaluation of Yield Components on Capsicum spp. under Two Production Systems Sorapong Benchasri Department of Plant Science, Faculty of Technology and Community Development, Thaksin University, Pa Phayom, Phatthalung, Thailand P.O. 93210 Email: [email protected] Sakunkan Simla Department of Agricultural Technology, Faculty of Technology, Mahasarakham University, Khamriang, Kantarawichai Maha Sarakham, Thailand P.O. 44150 Email: [email protected] Sirikan Pankaew Division of Student Affairs of Thaksin University, Pa Phayom, Phatthalung, Thailand P.O. 93210 Email:[email protected] Abstract—Thirty five lines of chilli were evaluated under part of Thailand as most food recipes in the South are inorganic and organic production systems. The objective of rather hot. this study was to compare crop performance of chilli lines in Nowadays, the increase in population, our compulsion terms of productivity that have good adaptation to inorganic is not only to stabilize agricultural production but also to and organic production systems. The chilli lines were increase it further in sustainable manner [3]. Excessive carried out a Randomized Complete Block Design under inorganic and organic production systems. The results use over years of agro-chemicals like pesticides and showed that there were highly significant (p≤0.01) for fertilizers has affected the soil health, leading to reduction number of fruits/plant and yield/plant. The highest number in crop yield and product quality [4]. Hence, a natural of quality fruits was found on Chee: approximately 519.42 balance needs to be maintained at all cost [5]-[8] and 512.69 fruits/plant under inorganic and organic Chilli cultivars with good adaptation to organic production systems, respectively. -

Development of Historical Tourism: a Case Study of Bangkok National Museum, Thailand

International Journal of Management and Applied Science, ISSN: 2394-7926 Volume-4, Issue-10, Oct.-2018 http://iraj.in DEVELOPMENT OF HISTORICAL TOURISM: A CASE STUDY OF BANGKOK NATIONAL MUSEUM, THAILAND. NUALMORAKOT TAWEETHONG Suan Sunandha Rajabhat University, Thailand E-mail: [email protected] Abstract - The objective of this research is to study the operating conditions and developmental problems and obstacles in development of historical tourism within Thailand as well as presenting development guidelines for historical tourism at the Bangkok National Museum, Thailand. This research will utilise qualitative research, including in-depth interview method as applied to data collection, with the key interviewees being key executive and operating officers in the Bangkok National Museum, tourists, tourism industry entrepreneurs and community leaders in the Phra Nakhon District (Bangkok) to represent a total of 70 persons. Data was analysed by utilising descriptive statistics, compiling of the acquired data. Studied phenomenon were examined through a determined analytical framework of analysis. This analytical framework considers four primary elements: finance and resources available to institutions, the level of service quality provided by the institutions, network learnings and development of institutions and the participation process of institutions. The research’s findings indicate that the National Museum’s operating condition could be developed to be a profitable historical tourism location and the developmental problems and obstacles were primarily issues of limited budgets for studies and research, conservation and collection of the important antiques, while tourism services and facilities had not yet been able to create a positive impression or experience for tourists, management lacked the facilitation of learning and developmental network in the group of the intellectuals or students and new generation youths with few participating intourism locations or the development of people or sites within local areas. -

Economic Empowerment for All: an Examination of Women's

Empowerment for all: an examination of women’s experiences and perceptions of economic empowerment in Maha Sarakham, Thailand A thesis submitted to the Graduate School Of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Community Planning In the School of Planning In the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning by Amber David B.A. The College of New Jersey March 2017 Committee Chair: David Edelman, Ph.D. Committee Member: Carolette Norwood, Ph.D. Abstract The year of 2015 was the culmination of the Millennium Development Goals, and the launch of the Sustainable Development Goals. Both the MDGs and SDGs recognize gender equality as a basic human right that, when coupled with women's empowerment, provides a vehicle for poverty eradication and economic development. This renewed global agenda sets the stage for the focus of this research: the investigation of the lived experience of women in northeastern Thailand as a window into their sense of economic empowerment. Via snowball sourcing, fifteen women in Maha Sarakham, Thailand were selected to participate in the study. Through in-depth interviews the researcher discovered that the Isan women of Maha Sarakham have used soft power to empower themselves in the short term and are leveraging higher education to create opportunities for the generations of women empowerment they are raising and influencing. II This Page Intentionally Left Blank. III Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to my thesis Chair, Dr. David Edelman of the DAAP School of Planning and my co-Chair, Dr. Carolette Norwood of Women and Gender Studies who have listened and offered guidance as I’ve unraveled, reconstructed, and deciphered all of the stories that I gathered. -

Nitrogen Flow Analysis from Different Land-Use of the Chi River Basin (Maha Sarakham Region, Thailand)

International Journal of GEOMATE, March., 2021, Vol.20, Issue 79, pp. 9-15 ISSN: 2186-2982 (P), 2186-2990 (O), Japan, DOI: https://doi.org/10.21660/2021.79.6165 Geotechnique, Construction Materials and Environment NITROGEN FLOW ANALYSIS FROM DIFFERENT LAND-USE OF THE CHI RIVER BASIN (MAHA SARAKHAM REGION, THAILAND) * Nida Chaimoon 1 1 Circular Resource and Environmental Protection Technology Research Unit (CREPT), Faculty of Engineering, Mahasarakham University, Thailand *Corresponding Author, Received: 03 Nov. 2020, Revised: 12 Jan. 2021, Accepted: 27 Jan. 2021 ABSTRACT: This paper aims at assessing the effect of land use on nitrogen flows from a significant land- use area in the Chi River basin (Maha Sarakham region) in Thailand. The Chi River is one of the main rivers, and many land use categories affect the quality of the river. Statistical data and referred data was collected as the secondary data from credible sources to identify the flows. The data show a strong effect of land use on nitrogen with the highest load dominated by paddy field (66,597.51 tonne/year), and the lowest value in the community (1,005.71 tonne/year). Nitrogen flow increased with the fertilizer application in paddy field and farm plants (34,834.07 tonne/year). Paddy field discharged nitrogen to the Chi River 47 tonne/year in form of surface runoff. Also, the community without wastewater collection system takes part in a non-point source (NPS) of nitrogen to the Chi River at 299 tonne/year. The management's suggestion is to control fertilizer application, burning of agricultural residue such as rice straw, and wastewater treatment before disposal. -

Preserving Temple Murals in Isan: Wat Chaisi, Sawatthi Village, Khon Kaen, As a Sustainable Model1

Preserving Temple Murals in Isan: Wat Chaisi, Sawatthi Village, Khon Kaen, as a Sustainable Model1 Bonnie Pacala Brereton Abstract—Wat Chaisi in Sawatthi village, Sawatthi District, located about twenty kilometers from the bustling provincial capital of Khon Kaen, is a unique example of local cultural heritage preservation that was accomplished solely through local stakeholders. Its buildings, as well as the 100 year-old murals on the ordination hall, have been maintained and are used regularly for merit- making and teaching. The effort was initiated by the abbot and is maintained through the joint effort of the wat community, Khon Kaen Municipality, and various individuals and faculties at Khon Kaen University. This paper will examine the role of local leadership in promoting local cultural heritage. Introduction Of the more than 40,000 Buddhist wats in Thailand seventeen percent, or nearly 7,000, are abandoned.2 Of those still in use, many are becoming increasingly crammed with seemingly superfluous new structures, statues, and decorations, funded by people seeking fame or improvement in their karmic status. Still others are thriving because of the donations they attract through their association with what is sometimes called “popular Buddhism,” a hodgepodge of beliefs in magical monks, amulets, saints, and new rituals aimed at bringing luck and financial success (Pattana 2012). Yet countless others are in a moribund state, in some cases tended by one or two elderly, frail monks who lack the physical and financial resources to maintain them. Both situations are related to the loss of cultural heritage, as countless unique 1 This paper is adapted from one presented at the Fifth International Conference on Local Government, held in Palembang, Indonesia, September 17-19, 2014. -

Kaempferia Mahasarakhamensis, a New Species from Thailand

Taiwania 64(1): 39-42, 2019 DOI: 10.6165/tai.2019.64.39 Kaempferia mahasarakhamensis, a new species from Thailand Surapon SAENSOUK1,2,* and Piyaporn SAENSOUK 1,3 1. Plant and Invertebrate Taxonomy and Its Applications Unit Group, Mahasarakham University, Thailand. 2. WalaiRukhavej Botanical Research Institute, Mahasarakham University, Kantarawichai District, Maha Sarakham, 44150, Thailand. 3. Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Mahasarakham University, Maha Sarakha 44150, Thailand. *Corresponding author’s email: [email protected] (Manuscript received 20 August 2018; accepted 21 January 2019; online published 31 January 2019) ABSTRACT: Kaempferia mahasarakhamensis sp. nov. (Zingiberaceae), a new species from Northeastern Thailand, is described, photographed and illustrated. It can be easily recognized by its erect and elongate psuedostem, length of leaf sheaths and leaves elliptic with apex acuminate. The new species resembles K. larsenii Sirirugsa but it differs in its two leaves, pseudostem high, blade broadly elliptic, leaf apex acute, length of leaf sheath, length of petiole, number flower per inflorescence, white flower and labellum white with two darker purple patches towards the base. KEY WORDS: Kaempferia mahasarakhamensis; Maha Sarakham; New species; Thailand; Zingiberaceae. INTRODUCTION coloration at margins, purple-blotched at apex, apex acute; sheaths 3, up to 6 cm long, glabrous, reddish. Kaempferia belongs to Zingiberaceae (Sirirugsa, Inflorescence terminal, contemporaneous with leafy- 1992 and Larsen and Larsen, 2006). It comprises about shoot, semi-sessile, 1/3rd remained enclosed by the leaf- 60 species geographically distributed from India to sheath, each inflorescence with 10–15 flowers which Southeast Asia, where Thailand appears to be the richest opens one (or two to three) after another. -

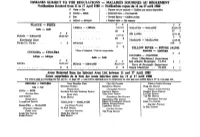

MALADIES SOUMISES AU RÈGLEMENT Notifications Received from 11 to 17 April 1980 — Notifications Reçues Dn 11 Au 17 Avril 1980 C Cases — C As

Wkly Epidem. Rec * No. 16 - 18 April 1980 — 118 — Relevé èpidém, hebd. * N° 16 - 18 avril 1980 investigate neonates who had normal eyes. At the last meeting in lement des yeux. La séné de cas étudiés a donc été triée sur le volet December 1979, it was decided that, as the investigation and follow et aucun effort n’a été fait, dans un stade initial, pour examiner les up system has worked well during 1979, a preliminary incidence nouveau-nés dont les yeux ne présentaient aucune anomalie. A la figure of the Eastern District of Glasgow might be released as soon dernière réunion, au mois de décembre 1979, il a été décidé que le as all 1979 cases had been examined, with a view to helping others système d’enquête et de visites de contrôle ultérieures ayant bien to see the problem in perspective, it was, of course, realized that fonctionné durant l’année 1979, il serait peut-être possible de the Eastern District of Glasgow might not be representative of the communiquer un chiffre préliminaire sur l’incidence de la maladie city, or the country as a whole and that further continuing work dans le quartier est de Glasgow dès que tous les cas notifiés en 1979 might be necessary to establish a long-term and overall incidence auraient été examinés, ce qui aiderait à bien situer le problème. On figure. avait bien entendu conscience que le quartier est de Glasgow n ’est peut-être pas représentatif de la ville, ou de l’ensemble du pays et qu’il pourrait être nécessaire de poursuivre les travaux pour établir le chiffre global et à long terme de l’incidence de ces infections.