Language Specific Peculiarities Document for Cebuano As Spoken

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RDO 83-Talisay CT Minglanilla

Republic of the Philippines DEPARTMENT OF FINANCE Roxas Boulevard Corner Vito Cruz Street Manila 1004 DEPARTMENT ORDER NO. 44-02 September 16, 2002 SUBJECT : IMPLEMENTATION OF THE REVISED ZONAL VALUES OF REAL PROPERTIES IN THE CITY OF TALISAY UNDER THE JURISDICTION OF REVENUE DISTRICT OFFICE NO. 83 (TALISAY CITY, CEBU), REVENUE REGION NO. 13 (CEBU CITY) FOR INTERNAL REVENUE TAX PURPOSES. TO : All Internal Revenue Officers and Others Concerned. Section 6 (E) of the Republic Act No. 8424, otherwise known as the "Tax Reform Act of 1997"' authorizes the Commissioner of Internal Revenue to divide the Philippines into different zones or areas and determine for internal revenue tax purposes, the fair market value of the real properties located in each zone or area upon consultation with competent appraisers both from private and public sectors. By virtue of said authority, the Commissioner of Internal Revenue has determined the zonal values of real properties (1st revision) located in the city of Talisay under the jurisdiction of Revenue District Office No. 83 (Talisay City, Cebu), Revenue Region No. 13 (Cebu City) after public hearing was conducted on June 7, 2000 for the purpose. This Order is issued to implement the revised zonal values for land to be used in computing any internal revenue tax. In case the gross selling price or the market value shown in the schedule of values of the provincial or city assessor is higher than the zonal value established herein, such values shall be used as basis for computing the internal revenue tax. This Order shall take effect immediately. -

Santander, Cebu DPWH, Cebu 4Th District Engineering Offic

Contract ID No. : 20HG0102 Contract Name : Local Program, Local Infrastructure Program, Local Roads and Bridges, Local Roads, Construction/Improvement of Municipal and Brgy. Road, Poblacion, Santander, Cebu Location of the Contract: Santander, Cebu DPWH, Cebu 4th District Engineering Office Poblacion, Dalaguete, Cebu Minutes of Pre-Bid Conference Date: February 4, 2020 1. Attendance: Present were: Bids and Awards Committee (BAC) BAC Secretariat 1. Renult G. Ricardo BAC Chairman (Regular) 1. Rosalind R. Vasquez - Head 2. Marlon 1. Mr. D. Renult Marollano G. Ricardo BAC Vice -–Chairman BAC Chairman (Regular) 1. Rosalind R. Vasquez – Head 2. Maria Lolita A. Castro – Member 3. Ma.2 .Ligaya Mr. Marlon A. Señor D. Marollano BAC Member – BAC (Regular) Member (Reg.) 2. Connie L. Caballo 3. Ms.4. AmeliaAmelia B. Caracut BAC– BA Member (Regular) 3. Zebedda B. Gudia 5. Jocelyn4. Mrs. F. EdnaOrcullo S. Manatad BAC Member - BAC (Provisional Member) (Prov.) 4. Nikki 4. Lolita B. Ordoña A. Castro 6. Edelberto R. Francisco BAC Member (Provisional) 5. Cyril5. Zebedda E. Alegado B. Gudia (End user for Construction ) 6. 6. Edward Nikki Ordona S. Butcon 7. Ryan V. Garma 8. Altius A. Enriquez 9. Jose Mario T. Rasco BAC - TWG 1. Edelberto 1. Sergio R. B. Francisco Bendulo, Jr. - Head - Head 2.2. Collin Sergio Mark B. Bendulo,Salvador Jr. - - Member 3. Dejose 3. Bryan Mae AB.. LabaoCampos 4. Elvin 4. Julrey C. Montalla H. Laput 5. Bryan B. 5. Campos Ralph Jocyph Alegado 6. Edna 6. Aljoy S. ManatadF. Orcullo 7. Connie7. Lenard L. PanugalinogCaballo 8. Jake8. Ryan Luis V. A. Garma Paires 9. -

SOIL Ph MAP N N a H C Bogo City N O CAMOT ES SEA CA a ( Key Rice Areas ) IL

Sheet 1 of 2 124°0' 124°30' 124°0' R E P U B L I C O F T H E P H I L I P P I N E S Car ig ar a Bay D E PA R T M E N T O F A G R IIC U L T U R E Madridejos BURE AU OF SOILS AND Daanbantayan WAT ER MANAGEMENT Elliptical Roa d Cor. Visa yas Ave., Diliman, Quezon City Bantayan Province of Santa Fe V IS A Y A N S E A Leyte Hagnaya Bay Medellin E L San Remigio SOIL pH MAP N N A H C Bogo City N O CAMOT ES SEA CA A ( Key Rice Areas ) IL 11°0' 11°0' A S Port Bello PROVINCE OF CEBU U N C Orm oc Bay IO N P Tabogon A S S Tabogon Bay SCALE 1:300,000 2 0 2 4 6 8 Borbon Tabuelan Kilom eter s Pilar Projection : Transverse Mercator Datum : PRS 1992 Sogod DISCLAIMER : All political boundaries are not authoritative Tuburan Catmon Province of Negros Occidental San Francisco LOCATION MA P Poro Tudela T I A R T S Agusan Del S ur N Carmen O Dawis Norte Ñ A Asturias T CAMOT ES SEA Leyte Danao City Balamban 11° LU Z O N 15° Negros Compostela Occi denta l U B E Sheet1 C F O Liloan E Toledo City C Consolacion N I V 10° Mandaue City O R 10° P Magellan Bay VIS AYAS CEBU CITY Bohol Lapu-Lapu City Pinamungajan Minglanilla Dumlog Cordova M IN DA NA O 11°30' 11°30' 5° Aloguinsan Talisay 124° 120° 125° ColonNaga T San Isidro I San Fernando A R T S T I L A O R H T O S Barili B N Carcar O Ñ A T Dumanjug Sibonga Ronda 10°0' 10°0' Alcantara Moalboal Cabulao Bay Badian Bay Argao Badian Province of Bohol Cogton Bay T Dalaguete I A R T S Alegria L O H O Alcoy B Legaspi ( ilamlang) Maribojoc Bay Guin dulm an Bay Malabuyoc Boljoon Madridejos Ginatilan Samboan Oslob B O H O L S E A PROVINCE OF CEBU SCALE 1:1,000,000 T 0 2 4 8 12 16 A Ñ T O Kilo m e te r s A N Ñ S O T N Daanbantayan R Santander S A T I Prov. -

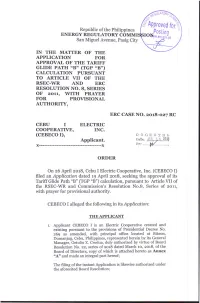

Initial Order ERC Case No. 2018-027 CF

- jlATO, 'Approved for Republic of the Philippines ENERGY REGULATORY COMMI Postinn '°1wercoph San Miguel Avenue, Pasig City IN THE MATTER OF THE APPLICATION FOR APPROVAL OF THE TARIFF GLIDE PATH "B" (TGP "B") CALCULATION PURSUANT TO ARTICLE VII OF THE RSEC-WR AND ERC RESOLUTION NO. 8, SERIES OF 2011, WITH PRAYER FOR PROVISIONAL AUTHORITY, ERC CASE NO. 2018-027 RC CEBU I ELECTRIC COOPERATIVE, INC. (CEBECO I), 1) 0 0 K E T 3 b Applicant. Date:, .i,014JL2LW X X ORDER On 26 April 2018, Cebu I Electric Cooperative, Inc. (CEBECO I) filed an Application dated 19 April 2018, seeking the approval of its Tariff Glide Path "B" (TGP "B") calculation, pursuant to Article VII of the RSEC-WR and Commission's Resolution No.8, Series of 2011, with prayer for provisional authority. CEBECO I alleged the following in its Application: THE APPLICANT 1. Applicant CEBECO I is an Electric Cooperative created and existing pursuant to the provisions of Presidential Decree No. 269 as amended, with principal office located at Bitoon, Dumanjug, Cebu, Philippines, represented herein by its General Manager, Getulio Z. Crodua, duly authorized by virtue of Board Resolution No. 22, series of 2018 dated March 10, 2018, of the Board of Directors, copy of which is attached hereto as Annex "A" and made an integral part hereof; The filing of the instant Application is likewise authorized under the aforecited Board Resolution; ERC CASE NO. 2018-027 RC ORDER/b July 2018 PAGE 2 OF 13 2. Applicant has been granted by the National Electrification Administration (NRA) an authority to operate and distribute electric light and power within the coverage area comprising the City of Carcar and the Municipalities of Barili, Dumanjug, Ronda, Alcantara, Moalboal, Badian, Alegria, Malabuyoc, Ginatilan, Samboan, Santander, Sibonga, Argao, Dalaguete, Alcoy, Boljo-on and Oslob, all in the Province of Cebu; THE APPLICATION AND ITS PURPOSE 3. -

Publications

Publications PHILIPPINE LANGUAGES: AS COLORFUL AS THE COUNTRY ITSELF by: Donna May S. Baltazar Teacher III, Orani National High School Parang - Parang The Philippines is an archipelagic country consisting of over seven thousand islands. With vast variation of landscapes and terrains. With the majority of the country being divided by either vast waters to huge mountain ranges, it is not surprising that there are also many variations in language. There are eight major dialects in the Philippines, not including sub-dialects. The first one is Bikol, the language use in the southern tip of the Luzon islands, the Bikol region, which includes Naga, Camarines Sur, Camarines Norte, Legazpi, and Albay, as well as parts of Surigao islands. The Bikol language is further divided to four sub- groups, the Northern Coastal Bikol, Southern Bikol language, Central Bikol language, and the Bisakol. Then there is the Cebuano language or also referred to as Visaya is the native language of the majority of people in the Visayan islands. The third one is Hiligaynon or the Ilonggo, which originated in Ilo-ilo still a part of the Visayan Islands. Hiligaynon is not as wide spread as that of Cebuano language, the native speakers are mostly concentrated in the Western Visayas region which includes Ilo-ilo, Capiz, Guimaraz, and Negros Occidental. Although some of the neighboring islands also adopted the language. Ilocano on the other hand is the language of the spoken in the Ilocos region as well as other northern provinces in the Philippines. Ilocano is the major spoken language in 22 November 2019 Publications the Northern Luzon. -

Ang Marks the What?: an Analysis of Noun Phrase Markers in Cebuano

Ang marks the what?: An analysis ofnoun phrase markers in Cebuano Senior Essay Department ofLinguistics, Yale University Advised by Claire Bowern and Robert Frank Ava Tattelman Parnes 10 May 2011 Acknowledgements: Words can barely express the gratitude I feel toward those who have helped me tackle this daunting project. I would like to thank my advisors, Professors Claire Bowem and Robert Frank, for guiding me through the research process, suggesting possible analyses, asking me the tough questions, and making me smile. They always made me feel supported and made what could have been a frustrating experience an enjoyable one. I could not have completed this essay without their incredible teaching skills and their dedication to working through the tough spots with me. I would also like to thank Professor Larry Hom, the Director ofUndergraduate Studies, and the rest ofthe senior linguistics majors for their support and ideas in the senior essay class. Lastly, lowe my understanding ofCebuano to one woman, Ms. Threese Serana. Her warm personality and connection to Cebuano are what helped me to become interested in the intricacies ofthe language two years ago. Her dedication to the discovery process that is elicitation made this project a joy. The sentences, stories, and excitement we shared while discovering things about Cebuano will remain with me long after this project is completed. Table of Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Overview ofEssay 1 1.2 Cebuano Language Information and History 1 1.3 Voice in Austronesian Languages 3 1.4 Noun Phrase -

GAPAS (COTTON, Gossypmium Hirsutum) AS TEXTILE and MEDICINE in SANTANDER, CEBU

A DISAPPEARING TRADITION: GAPAS (COTTON, Gossypmium hirsutum) AS TEXTILE AND MEDICINE IN SANTANDER, CEBU Zona Hildegarde S. Amper The utilization of available flora (and fauna), is closely linked to culture as well as to the larger national and international forces which affect local environments. The proliferation of specific species in a given locale largely depends on how it is utilized. This paper documents local knowledge on gapas or cotton [Gossypmium hirsutum] as crop, as textile and as medicine over time in Santander, a south- eastern Cebu town, in order to determine its place in Santander culture and recommend steps for the conservation and revitalization of an important natural and cultural heritage. External forces such as the market have affected the proliferation of gapas (cotton) as a crop in this town. Keywords: Ecological anthropology, cotton, local knowledge, natural cultural heritage Introduction The current study revolves around the cotton plant traditionally grown in a south-eastern town of Cebu, the Philippines and how its proliferation and utilization in the locality has been affected by colonial and post-colonial market forces over time. Ecological anthropologists have studied various strategies of human adaptation to as well as human impacts on the environment. Ethnoecology as a field in ecological anthropology explores how nature is viewed by human cultures through their beliefs and knowledge, and how distinct groups of humans manage natural resources (Toledo 2002). Larger national and international forces have however affected how human cultures currently utilize natural resources; with the rapidly expanding world capitalist system and globalization, local cultures’ utilization of existing flora and fauna has been affected. -

CEBUANO for BEGINNERS PALI Language Texts: Philippines (Pacific and Asian Linguistics Institute) Howard P

CEBUANO FOR BEGINNERS PALI Language Texts: Philippines (Pacific and Asian Linguistics Institute) Howard P. McKaughan Editor CEBUANO FOR BEGINNERS by Maria Victoria R. Bunye and Elsa Paula Yap University of Hawaii Press Honolulu 1971 Open Access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Licensed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Inter- national (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0), which permits readers to freely download and share the work in print or electronic format for non-commercial purposes, so long as credit is given to the author. The license also permits readers to create and share de- rivatives of the work, so long as such derivatives are shared under the same terms of this license. Commercial uses require permission from the publisher. For details, see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/. The Cre- ative Commons license described above does not apply to any material that is separately copyrighted. Open Access ISBNs: 9780824879778 (PDF) 9780824879761 (EPUB) This version created: 30 May, 2019 Please visit www.hawaiiopen.org for more Open Access works from University of Hawai‘i Press. The work reported herein was performed pursuant to a contract with the Peace Corps, Washington, D.C. 20525. The opinions ex- pressed herein are those of the authors and should not be con- strued as representing the opinions or policy of any agency of the United States Government. Copyright © 1971 by University of Hawaii Press All rights reserved PREFACE The lessons herein were developed under a contract with the Peace Corps (PC 25–1507) at the University of Hawaii under the auspices of the Pacific and Asian Linguistics Institute. -

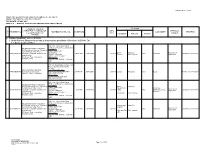

A. MINING TENEMENT APPLICATIONS 1. Under Process (Returned Pursuant to the Pertinent Provisions of Section 4 of EO No

ANNEX B Page 1 of 105 MINES AND GEOSCIENCES BUREAU REGIONAL OFFICE NO. VII MINING TENEMENTS STATISTICS REPORT FOR MONTH OF MAY, 2017 ANNEX B - MINERAL PRODUCTION SHARING AGREEMENT (MPSA) TENEMENT HOLDER/ LOCATION line PRESIDENT/ CHAIRMAN OF AREA PREVIOUS TENEMENT NO. ADDRESS/FAX/TEL. NO. DATE FILED COMMODITY REMARKS no. THE BOARD/CONTACT (has.) Barangay/s Mun./City Province HOLDER PERSON A. MINING TENEMENT APPLICATIONS 1. Under Process (Returned pursuant to the pertinent provisions of Section 4 of EO No. 79) 1.1. By the Regional Office 25th Floor, Petron Mega Plaza 358 Sen. Gil Puyat Ave., Makati City Apo Land and Quarry Corporation Cebu Office: Mr. Paul Vincent Arcenas - President Tinaan, Naga, Cebu Contact Person: Atty. Elvira C. Contact Nos.: Bairan Naga City Apo Cement 1 APSA000011VII Oquendo - Corporate Secretary and 06/03/1991 10/02/2009 240.0116 Cebu Limestone Returned on 03/31/2016 (032)273-3300 to 09 Tananas San Fernando Corporation Legal Director FAX No. - (032)273-9372 Mr. Gery L. Rota - Operations Manila Office: Manager (Cebu) (632)849-3754; FAX No. - (632)849- 3580 6th Floor, Quad Alpha Centrum, 125 Pioneer St., Mandaluyong City Tel. Nos. Atlas Consolidated Mining & Cebu Office (Mine Site): 2 APSA000013VII Development Corporation (032) 325-2215/(032) 467-1408 06/14/1991 01/11/2008 287.6172 Camp-8 Minglanilla Cebu Basalt Returned on 03/31/2016 Alfredo C. Ramos - President FAX - (032) 467-1288 Manila Office: (02)635-2387/(02)635-4495 FAX - (02) 635-4495 25th Floor, Petron Mega Plaza 358 Sen. Gil Puyat Ave., Makati City Apo Land and Quarry Corporation Cebu Office: Mr. -

Survey of Malabuyoc Geothermal

Proceedings World Geothermal Congress 2005 Antalya, Turkey, 24-29 April 2005 Controlled Source Magnetotelluric (CSMT) Survey of Malabuyoc Thermal Prospect, Malabuyoc/Alegria, Cebu, Philippines R.A.Del Rosario, Jr., M.S. Pastor and R.T. Malapitan Geothermal and Coal Division, Energy Resource Development Bureau, Department of Energy, Energy Center, Merritt Road, Ft. Bonifacio, Taguig, MM, Philippines [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Keywords: Controlled Source Magnetotelluric, Malabuyoc, From Cebu City, the town of Malabuyoc is about 123 kms MRF or 4-hour drive via Car-Car-Dalaguete-Ginatilan Provincial Highway or about 3-hour via Car-Car Barili Road going ABSTRACT south to Ginatilan. From Malabuyoc proper, the thermal spring is located north-northwest in Brgy. Montaneza. It The Controlled Source Magnetotelluric (CSMT) survey could be reached via barangay road leading to Sitio Mainit, conducted at Malabuyoc geothermal prospect aims at where the thermal spring is situated. establishing the presence and extent of hot water to a medium depth of 300-500 meters for non-electrical applications of geothermal fluids. The resistivity anomalies in the prospect are largely controlled by geologic structure (faulted anticlinal structure). VISAYAN SEA P h The Malabuyoc system is categorized as a basement aquifer i l ip P p HI i beneath a sedimentary basin with the heated fluid probably Y n Tacloban City L A e I P N F P A Iloilo I a NE originating at the center of the basin east of the survey area. P u Basin l t Z The fluid is channeled along the Middle Diagonal and Iloilo City o n U e S Montañeza River Faults (MRF) and emerged along the Bacolod City B E E A C stretch of Montaneza River as warm seepages. -

Report for the Berkeley Script Encoding Initiative

Indonesian and Philippine Scripts and extensions not yet encoded or proposed for encoding in Unicode as of version 6.0 A report for the Script Encoding Initiative Christopher Miller 2011-03-11 Christopher Miller Report on Indonesian and the Philippine scripts and extensions Page 2 of 60 Table of Contents Introduction 4 The Philippines 5 Encoded script blocks 5 Tagalog 6 The modern Súlat Kapampángan script 9 The characters of the Calatagan pot inscription 12 The (non-Indic) Eskayan syllabary 14 Summary 15 Sumatra 16 The South Sumatran script group 16 The Rejang Unicode block 17 Central Malay extensions (Lembak, Pasemah, Serawai) 18 Tanjung Tanah manuscript extensions 19 Lampung 22 Kerinci script 26 Alleged indigenous Minangkabau scripts 29 The Angka bejagung numeral system 31 Summary 33 Sumatran post-Pallava or “Malayu” varieties 34 Sulawesi, Sumbawa and Flores islands 35 Buginese extensions 35 Christopher Miller Report on Indonesian and the Philippine scripts and extensions Page 3 of 60 The Buginese Unicode block 35 Obsolete palm leaf script letter variants 36 Luwu’ variants of Buginese script 38 Ende script extensions 39 Bimanese variants 42 “An alphabet formerly adopted in Bima but not now used” 42 Makassarese jangang-jangang (bird) script 43 The Lontara’ bilang-bilang cipher script 46 Old Minahasa script 48 Summary 51 Cipher scripts 52 Related Indian scripts 52 An extended Arabic-Indic numeral shape used in the Malay archipelago 53 Final summary 54 References 55 1. Introduction1 A large number of lesser-known scripts of Indonesia and the Philippines are not as yet represented in Unicode. Many of these scripts are attested in older sources, but have not yet been properly documented in the available scholarly literature. -

Today in the History of Cebu

Today in the History of Cebu Today in the History of Cebu is a record of events that happened in Cebu A research done by Dr. Resil Mojares the founding director of the Cebuano Studies Center JANUARY 1 1571 Miguel Lopez de Legazpi establishing in Cebu the first Spanish City in the Philippines. He appoints the officials of the city and names it Ciudad del Santisimo Nombre de Jesus. 1835 Establishment of the parish of Catmon, Cebu with Recollect Bernardo Ybañez as its first parish priest. 1894 Birth in Cebu of Manuel C. Briones, publisher, judge, Congressman, and Philippine Senator 1902 By virtue of Public Act No. 322, civil government is re established in Cebu by the American authorities. Apperance of the first issue of Ang Camatuoran, an early Cebu newspaper published by the Catholic Church. 1956 Sergio Osmeña, Jr., assumes the Cebu City mayorship, succeeding Pedro B. Clavano. He remains in this post until Sept.12,1957 1960 Carlos J. Cuizon becomes Acting Mayor of Cebu, succeeding Ramon Duterte. Cuizon remains mayor until Sept.18, 1963 . JANUARY 2 1917 Madridejos is separated from the town of Bantayan and becomes a separate municipality. Vicente Bacolod is its first municipal president. 1968 Eulogio E. Borres assumes the Cebu City mayorship, succeeding Carlos J. Cuizon. JANUARY 3 1942 The “Japanese Military Administration” is established in the Philippines for the purpose of supervising the political, economic, and cultural affairs of the country. The Visayas (with Cebu) was constituted as a separate district under the JMA. JANUARY 4 1641 Volcanoes in Visayas and Mindanao erupt simultaneously causing much damage in the region.