Historic Preservation Is Part of the DNA of Pittsburgh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 FINAL REPORT-NORTHSIDE PITTSBURGH-Bob Carlin

1 FINAL REPORT-NORTHSIDE PITTSBURGH-Bob Carlin-submitted November 5, 1993 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I Fieldwork Methodology 3 II Prior Research Resources 5 III Allegheny Town in General 5 A. Prologue: "Allegheny is a Delaware Indian word meaning Fair Water" B. Geography 1. Neighborhood Boundaries: Past and Present C. Settlement Patterns: Industrial and Cultural History D. The Present E. Religion F. Co mmunity Centers IV Troy Hill 10 A. Industrial and Cultural History B. The Present C. Ethnicity 1. German a. The Fichters 2. Czech/Bohemian D. Community Celebrations V Spring Garden/The Flats 14 A. Industrial and Cultural History B. The Present C. Ethnicity VI Spring Hill/City View 16 A. Industrial and Cultural History B. The Present C. Ethnicity 1. German D. Community Celebrations VII East Allegheny 18 A. Industrial and Cultural History B. The Present C. Ethnicity 1. German a. Churches b. Teutonia Maennerchor 2. African Americans D. Community Celebrations E. Church Consolidation VIII North Shore 24 A. Industrial and Cultural History B. The Present C. Community Center: Heinz House D. Ethnicity 1. Swiss-German 2. Croatian a. St. Nicholas Croatian Roman Catholic Church b. Javor and the Croatian Fraternals 3. Polish IX Allegheny Center 31 2 A. Industrial and Cultural History B. The Present C. Community Center: Farmers' Market D. Ethnicity 1. Greek a. Grecian Festival/Holy Trinity Church b. Gus and Yia Yia's X Central Northside/Mexican War Streets 35 A. Industrial and Cultural History B. The Present C. Ethnicity 1. African Americans: Wilson's Bar BQ D. Community Celebrations XI Allegheny West 36 A. -

Operating and Capital Improvement Budget July 1, 2018 - Jurte 30, 2019 Fiscal Year 2019

Operating and Capital Improvement Budget July 1, 2018 - Jurte 30, 2019 Fiscal Year 2019 PortAuthority.o rg This page intentionally left blank Board of Directors Officers Jeffrey W. Letwin, Esq., Chairperson of the Board of Directors Jennifer M. Liptak, Vice Chairperson of the Board of Directors Senator Jim Brewster, Secretary of the Board of Directors Directors Representative Dom Costa Robert J. Kania, Jr. Ann Ogoreuc D. Raja John L. Tague, Jr. Stephanie Turman Robert Vescio Michelle Zmijanac 2 | P a g e Chief Executive Officer Katharine Eagan Kelleman Officers and Assistant General Managers Barry Adams, Chief Human Resources Officer Michael Cetra, Chief Legal Officer Jeffrey Devlin, Chief Information Officer David Huffaker, Chief Development Officer William Miller, Chief Operations Officer James Ritchie, Chief Communications Officer Peter Schenk, Chief Financial Officer Heinz 57 Center 345 Sixth Avenue Floor 3 Pittsburgh, PA 15222-2327 (412) 566-5500 www.portauthority.org 3 | P a g e FY 2019 Operating and Capital Table of Contents Improvement Budget Board of Directors ......................................................................................................................................... 2 Officers and Assistant General Managers ..................................................................................................... 3 Regional and Port Authority Profile .............................................................................................................. 6 Allegheny County ..................................................................................................................................... -

The One Northside Community Plan

Strategy Guide No. 1 Sharing New Methods˙ to IMPACT Pittsburgh’s Neighborhoods innovative project report: THE ONE NORTHSIDE COMMUNITY PLAN Our mission is to support the people, organizations and partnerships committed to creating and maintaining thriving neighborhoods. We believe that Pittsburgh’s future is built upon strong neighborhoods and the good work happening on the ground. It is integral to our role as an advocate, collaborator and convener to lift up exemplary projects and share best practices in ways that advance better engagement and community-led decisions and ensure a better understanding of the processes that lead to success and positive impact on our neighborhoods. We share this story with you to inspire action and celebrate progress, and most importantly, to empower leaders and residents in other communities to actively ˙ shape the future of their neighborhoods. — Presley L. Gillespie President, Neighborhood Allies Neighborhood Strategy Guide || 1 innovative project report: From concept to consensus Upwards of 600 people braved the chill of an early December night in Pittsburgh last year to celebrate in the warmth inside Heinz Field, home of the Pittsburgh Steelers. Their reason for celebration had nothing to do with the exploits of the city’s beloved professional football team. A community plan was being unveiled for improving the quality of life in the city’s Northside neighborhoods around the stadium that the voices of several thousand residents and community stakeholders had shaped. And hopes were high that improvements in infrastructure, schools, employment and lives would be more broadly and quickly realized, as they had in other city neighborhoods where resources and revitalization were attracting investment and people. -

The Physical and Cultural Development of Pittsburgh's Highland Park Neighborhood, 1778-1900

1 Building a Community: The Physical and Cultural Development of Pittsburgh’s Highland Park Neighborhood, 1778-1900 Nathaniel Mark, The Johns Hopkins University1 INTRODUCTION American history has a unique relationship with suburban residential life. Unlike many of their continental European counterparts, American commuter suburbs since their inception in the 19th century have been a symbol of the growing wealth of the American population. Indeed, suburban life and the American dream are often analogous concepts. Since Pittsburgh emerged as an industrial city, its suburbs have steadily grown from small upper-class rural retreats into the most prominent form of residential communities in Western Pennsylvania.2 Yet, the dominance of suburbs was not the inevitable outcome of industrialization. Prior to the latter half of the 19th century it was not even apparent that Pittsburgh’s well-to- do would rather live in peripheral areas than in the inner city. 1 This research was conducted as an undergraduate sophomore thesis in history. It was completed in 2012. Contact the author at [email protected] or through his website at https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Nathaniel_Mark/. 2 Frank Hobbs and Nicole Stoops, U.S. Census Bureau, Census 2000 Special Reports, Series CENSR-4, Demographic Trends in the 20th Century (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2002), 33. 2 Many historians and sociologists have analyzed the intricate process of early suburban development, and how these suburbs acquired the reputation of wealth and power that have remained a part of the suburban legacy. Sam Bass Warner, in his pioneering 1962 book Streetcar Suburbs, describes how Boston was transformed from a walking city to a modern metropolis. -

March/April 2010 (PDF)

the magazine of the master builders’ association of western pennsylvania march/april 2010 Oakland A Neighborhood In Demand EPA stormwAtEr rEgulAtions Add cost mAnAging thE rEcEssion biggEst risks mbA building ExcEllEncE winnErs ArrA first yEAr rEPort cArd BG Mar_Apr_10.indd 1 3/8/10 12:43 PM To start your development project make One-STOp at L.r. kimbaLL BEDROCK REPUTATION. STEADFAST PRINCIPLES. TARgETED RESULTS. ExPERTLy MANAgED. Developers call on our 56 years of experience and L.R. Kimball has provided one-stop services for many in-house capabilities to provide one-stop support from: of Pennsylvania’s most successful developments such as: • Civil and Environmental Specialists offering laboratory testing, civil site services, geotechnical • Innovation Park in State College drilling, soils and concrete testing, aerial mapping • Southpointe II in Washington County and surveying • Cherrington Office Park in Allegheny County • Traffic Experts who perform traffic studies and • Heinz Field Site Plan for the Pittsburgh Sports and obtain highway occupancy permits Exhibition Authority • Architecture Teams who design state-of-the-art • More than a dozen Wal-Mart, Lowe’s, LEED® certified facilities and Sam’s Club complexes With the heritage of a family-owned business that WE STAKE OUR REPUTATION ON IT. operates on a national scale, L.R. Kimball has L.R. Kimball will always do our best to ensure that assisted with hundreds of warehouse, office, retail your goals are met and that you receive the highest and mixed-use construction projects drawing from possible value. a range of over 60 integrated services to become a solid choice of developers in Pennsylvania. -

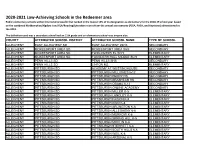

2020-2021 Low-Achieving Schools in the Redeemer Area

2020-2021 Low-Achieving Schools in the Redeemer area Public elementary schools within this Commonwealth that ranked in the lowest 15% of its designation as elementary for the 2018-19 school year based on the combined Mathematics/Algebra I and ELA/Reading/Literature scores from the annual assessments (PSSA, PASA, and Keystone) administered in the 2019. The definition used was a secondary school had an 11th grade and an elementary school was anyone else. COUNTY ATTRIBUTED SCHOOL DISTRICT ATTRIBUTED SCHOOL NAME TYPE OF SCHOOL ALLEGHENY EAST ALLEGHENY SD EAST ALLEGHENY JSHS SECONDARY ALLEGHENY MCKEESPORT AREA SD MCKEESPORT AREA SHS SECONDARY ALLEGHENY MCKEESPORT AREA SD TWIN RIVERS EL SCH ELEMENTARY ALLEGHENY MCKEESPORT AREA SD FOUNDERS HALL MIDDLE SCH ELEMENTARY ALLEGHENY PENN HILLS SD PENN HILLS SHS SECONDARY ALLEGHENY PENN HILLS SD LINTON MS ELEMENTARY ALLEGHENY PITTSBURGH SD ACADEMY AT WESTINGHOUSE SECONDARY ALLEGHENY PITTSBURGH SD PITTSBURGH MILLIONES 6-12 SECONDARY ALLEGHENY PITTSBURGH SD PITTSBURGH PERRY HS SECONDARY ALLEGHENY PITTSBURGH SD PITTSBURGH BRASHEAR HS SECONDARY ALLEGHENY PITTSBURGH SD PITTSBURGH OBAMA 6-12 SECONDARY ALLEGHENY PITTSBURGH SD PITTSBURGH ONLINE ACADEMY SECONDARY ALLEGHENY PITTSBURGH SD PITTSBURGH MILLER K-5 ELEMENTARY ALLEGHENY PITTSBURGH SD PITTSBURGH LANGLEY K-8 ELEMENTARY ALLEGHENY PITTSBURGH SD PITTSBURGH FAISON K-5 ELEMENTARY ALLEGHENY PITTSBURGH SD PITTSBURGH KING K-8 ELEMENTARY ALLEGHENY PITTSBURGH SD PITTSBURGH ARLINGTON K-8 ELEMENTARY ALLEGHENY PITTSBURGH SD PITTSBURGH ALLEGHENY 6-8 ELEMENTARY ALLEGHENY -

Pittsburgh, PA Previous GTCA City 2013

Pittsburgh, PA Previous GTCA City 2013 Contact: Tom Piccone ([email protected]); Andy Wang ([email protected]) The Church of God in Pittsburgh The Church of God in Pittsburgh was originally established as the Church in Pittsburgh in 1983, primarily through a migration of saints mainly from Ohio. Some years after a turmoil, the Church of God in Pittsburgh was incorporated in 2017. The church does not presently have a meeting hall, but meets on university campuses and in various saints’ homes. Approximately 40 currently gather on Lord’s Day mornings, including four children. The racial composition of the church is 59% Chinese and 16% Caucasian, with the remaining 25% a mix of Korean, Vietnamese, Black, and Indian. The current church life in Pittsburgh focuses primarily on campus work at the University of Pittsburgh (Pitt) and Carnegie Mellon University (CMU), though the need to gain more families is of equal priority (and not necessarily separate). Each year, the Lord adds remaining fruit to His Body through the saints’ labor on the campuses to gain college and graduate students, and sometimes university staff. In the past 12 years of campus work, dozens have been gained, but most have moved away. Only a handful of them have not been Asian. While the saints in Pittsburgh welcome all who would like to move here, we particularly see a need for young American families to migrate to the Pittsburgh area in order to share the burden of shepherding and gaining some from the population of American students and families for the strengthening of His testimony in this locality and region. -

Nathan Hart, AIA Oakland Square Historic District, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Nathan Hart, AIA Oakland Square Historic District, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania In 2004, I nominated my neighborhood of Oakland Square as a City of Pittsburgh historic district. My neighborhood faced, and continues to face, a demographic challenge. Many of the homeowners in the neighborhood are older. Many houses in Oakland have passed hands from older residents to absentee landlords. We feared that in a few years, if more young homeowners and families were not attracted to our neighborhood, the Oakland Square neighborhood could reach a tipping point at which poorly managed and maintained student housing would quickly erode property values and quality of life and drive out the base of home ownership that we currently enjoy. The nomination was contentious. On one hand, folks were concerned that a new layer of bureaucracy would govern what they could do to the exterior of their homes. Some older residents had significantly altered their houses and were concerned that they would be forced to spend more money than they could afford to restore their homes back to what they looked like in 1890. Several Oakland landlords fed on this fear with a misinformation campaign aimed at our Italian immigrant population. Other neighbors saw it as a way to maintain quality, reinvestment, and homeownership in the neighborhood. Just as a poorly maintained or unattractive building can make an entire street less attractive, a charming, well maintained building is an asset for its neighbors. Historic districts help promote a consistently high quality of materials, details, and styles throughout a neighborhood so that the district is a collection of charming, well maintained buildings. -

City of Pittsburgh Neighborhood Profiles Census 2010 Summary File 1 (Sf1) Data

CITY OF PITTSBURGH NEIGHBORHOOD PROFILES CENSUS 2010 SUMMARY FILE 1 (SF1) DATA PROGRAM IN URBAN AND REGIONAL ANALYSIS UNIVERSITY CENTER FOR SOCIAL AND URBAN RESEARCH UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH JULY 2011 www.ucsur.pitt.edu About the University Center for Social and Urban Research (UCSUR) The University Center for Social and Urban Research (UCSUR) was established in 1972 to serve as a resource for researchers and educators interested in the basic and applied social and behavioral sciences. As a hub for interdisciplinary research and collaboration, UCSUR promotes a research agenda focused on the social, economic and health issues most relevant to our society. UCSUR maintains a permanent research infrastructure available to faculty and the community with the capacity to: (1) conduct all types of survey research, including complex web surveys; (2) carry out regional econometric modeling; (3) analyze qualitative data using state‐of‐the‐art computer methods, including web‐based studies; (4) obtain, format, and analyze spatial data; (5) acquire, manage, and analyze large secondary and administrative data sets including Census data; and (6) design and carry out descriptive, evaluation, and intervention studies. UCSUR plays a critical role in the development of new research projects through consultation with faculty investigators. The long‐term goals of UCSUR fall into three broad domains: (1) provide state‐of‐the‐art research and support services for investigators interested in interdisciplinary research in the behavioral, social, and clinical sciences; (2) develop nationally recognized research programs within the Center in a few selected areas; and (3) support the teaching mission of the University through graduate student, post‐ doctoral, and junior faculty mentoring, teaching courses on research methods in the social sciences, and providing research internships to undergraduate and graduate students. -

Free Guided Tours 2019 Update 3-18 Copy.Qxp (Page 2)

free guided tours 2019 update 3-18 copy.qxp 3/25/19 1:41 PM Page 2 Free Guided Walking Tours Pittsburgh-Area in Downtown Pittsburgh and Oakland Neighborhood Walking Tours Wednesdays and Fridays: May through October 2019 Explore City and County Neighborhoods with docents from the Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation. Two different free guided walking tours are offered each month: tours on Wednesdays are Most tours are offered on several dates. For meeting locations and details, visit www.phlf.org; click on Tours & Events. from 10:00 to 11:00 a.m. and tours on Fridays are from Noon to 1:00 p.m. The tours feature Tour fees: PHLF members $10 per person; non-members $20 per person. different areas in Downtown Pittsburgh and in the city’s Oakland neighborhood. Advance paid reservations are required: [email protected] or 412-471-5808, ext. 527. Advance reservations are appreciated: [email protected]; 412-471-5808, ext. 527. WEDNESDAYS FRIDAYS APRIL AUGUST All event details are South Side, Pittsburgh subject to change. 10:00 to 11:00 a.m. Noon to 1:00 p.m. 28: 4: Eastern Shadyside, Pittsburgh Two Faces of Urban Renewal: Visit www.phlf.org MAY 6: May 1, 8, 15, 22, 29 May 3, 10, 17, 24, 31 Gateway Center and Market Square, for up-to-date Grant Street Upper Penn-Liberty 4: Sharpsburg, PA Downtown Pittsburgh information and click ALSO: (from Sixth to Liberty Avenues) 5: Automobile Row (Bloomfield/Friendship), 20: The Courthouse & City-County on Tours & Events. Free Tours at Meet Downtown at 980 Liberty Avenue Meet Downtown on Grant Street near outside -

Department of City Planning's

Division of Zoning and Development Review City of Pittsburgh, Department of City Planning 200 Ross Street, Third Floor Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15219 HISTORIC REVIEW COMMISSION OF PITTSBURGH Properties that are Designated as City Landmarks or are Located in City Designated Historic Districts Revised June 2019 Key: ALL COMMONS Allegheny Commons Parks Historic Site ALL WEST Allegheny West Historic District ALPHA TERRACE Alpha Terrace Historic District DEUTSCHTOWN Deutschtown Historic District EAST CARSON East Carson Street Historic District INDIVIDUAL Individually Designated City Historic Structure LEMMON ROW Lemmon Row Historic District MANCHESTER Manchester Historic District MARKET SQUARE Market Square Historic District MEX WAR STREETS Mexican War Streets Historic District MURRAY HILL Murray Hill Avenue Historic District OAKLAND Oakland Civic Historic District OAKLAND SQUARE Oakland Square Historic District PENN-LIBERTY Penn-Liberty Historic District ROSLYN FARMS Roslyn Farms Historic District SCHENLEY FARMS Schenley Farms Historic District NOMINATED Nominated for Historic Designation STREET ADDRESS HISTORIC DISTRICT 43rd Street 160 (Turney House) INDIVIDUAL 46th Street 340 (St. Mary’s Academy) INDIVIDUAL 172 (Peterson House) INDIVIDUAL Abdell Street 1006-1014 (even) MANCHESTER Adams Street 1307-1445 (odd) MANCHESTER 1400-1438 (even) MANCHESTER Allegheny Avenue 1100 ALL WEST 920 (Calvary Methodist Church) INDIVIDUAL 1001-1207 (odd) MANCHESTER 1305-1315 (odd) MANCHESTER 1501-1513 (odd) MANCHESTER Allegheny Commons Allegheny Commons Parks ALL COMMONS (North, West, and East Parks) Allegheny Square Allegheny Library INDIVIDUAL Pittsburgh Children’s Museum INDIVIDUAL (former Old Allegheny Post Office) Former Buhl Planetarium Building INDIVIDUAL Alger Street 1 (Greenfield Elementary School) INDIVIDUAL Apple Avenue 7101 (National Negro Opera House) INDIVIDUAL Arch Street 810 (Allegheny Middle School) INDIVIDUAL 1416 (former Engine House No. -

North Shore's Newest Development

NORTH SHORE’S NEWEST DEVELOPMENT NORTH SHORE DRIVE PITTSBURGH SAMPLE RENDERING SINCE ITS BEGINNING AS HOME TO THREE RIVERS STADIUM, THE NORTH SHORE HAS BECOME ONE OF PITTSBURGH’S MOST POPULAR ENTERTAINMENT DESTINATIONS. NOW HOME TO PNC PARK (PITTSBURGH PIRATES) AND HEINZ FIELD (PITTSBURGH STEELERS AND PITT PANTHERS), THE NORTH SHORE IS SO MUCH MORE THAN JUST GAME DAYS. DIRECTLY ADJACENT TO PNC PARK, THE NORTH SHORE’S NEWEST DEVELOPMENT WILL FEATURE STREET-LEVEL RETAIL SPACE WITH OFFICE AND RESIDENTIAL UNITS ABOVE AND AN ATTACHED PARKING STRUCTURE. COMING SOON NEW DEVELOPMENT Aerial View Site Plan Residential Entrance Gen. Tank Room Vestibule 101 110d COMING SOON Main Office Res. Corridor NEW Elec. 104 110c DEVELOPMENT Room 103 Trash Comp. 102 Egress Corridor Res. Mail 106 & Outdoor Storage Retail Loading Under Zone Res. Lobby Res. Lobby 105 110b Canopy 110a 114a Trash Room UP UP 107 Main Lobby 110 Transformer Rec. Retail Res. Office 100 Desk 113 Elev. Elev. Stair 1 Stair 2 ST-1 ST-2 Fire Comm. 112 Outdoor Retail Under Retail Project Name 109 Vestibule Canopy North Shore Lot 10 - 110e 113a Parking Garage Project Number 17021 H20 Service Client 111 Continental Real MOVE 1st Floor Estate Companies FACADE SOUTH for Drawing Title WHOLE DIMENSION #Layout Name Issue Date 1 1st Floor Sketch Number A-8 SCALE: 1/16" = 1'-0" A-8 Burgatory | North Shore Local Attractions Restaurants • gi-jin • Ruth’s Chris Steak House • The Eagle Beer & Food Hall • Sharp Edge Bistro • Gaucho’s • TGI Friday’s • The Foundry | Table & Tap • Ten Penny • Shorty’s Pins x Pints (coming soon) • The Terrace Room • The Speckled Egg • Talia • Tequila Cowboy • Vallozzi’s • Bar Louie • Andrew’s Steak and Seafood • Union Standard • Hyde Park Prime Steakhouse • Eddie V’s • Jerome Bettis 36 Grille • Braddock’s Rebellion • Wheelhouse Bar and Grill • Butcher and the Rye • Southern Tier Brewery • The Capital Grille • Burgatory • Eddie Merlot’s • Condado Tacos • Bridges & Bourbon • City Works • Fl.