First Record of Orchelimum Silvaticum East of Ohio, with Notes on Two Adventive Katydids from Long Island

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolution of Complex Calls in Meadow

THE EVOLUTION OF COMPLEX CALLS IN MEADOW KATYDIDS _______________________________________ A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy _____________________________________________________ by NATHAN HARNESS Dr. Johannes Schul, Dissertation Supervisor July 2018 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled THE EVOLUTION OF COMPLEX CALLS IN MEADOW KATYDIDS presented by Nathan Harness, a candidate for the degree of doctor of philosophy, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor Johannes Schul Professor Sarah Bush Professor Lori Eggert Professor Patricia Friedrichsen For my family Rachel and Mayr have given me so much. They show me unselfish affection, endless support, and generosity that seems to only grow. Without them the work here, and the adventure we’ve all three gone on surrounding it, would not have been possible. They have sacrificed birthdays, anniversaries, holidays, and countless weekends and evenings. They’ve happily seen me off to weeks of field work and conference visits. I am thankful to them for being so generous, and completely lacking in resentment at all the things that pull their husband and dad in so many directions. They have both necessarily become adept at melting away anxiety; I will forever be indebted to the hugs of a two-year-old and the kind words of his mom. Rachel and Mayr both deserve far more recognition than is possible here. I also want to thank my parents and brother and sisters. -

(Orthoptera: Tettigoniidae) Species Composition and Size Across Latitude in Atlantic Coast Salt Marshes

Estuaries and Coasts: J CERF (2008) 31:335–343 DOI 10.1007/s12237-007-9026-3 Grasshopper (Orthoptera: Tettigoniidae) Species Composition and Size Across Latitude in Atlantic Coast Salt Marshes Elizabeth L. Wason & Steven C. Pennings Received: 14 June 2007 /Revised: 5 November 2007 /Accepted: 16 November 2007 /Published online: 16 January 2008 # Coastal and Estuarine Research Federation 2007 Abstract Although grasshoppers are common salt marsh Geographic variation in species composition and body size herbivores, we know little about geographic variation in of grasshoppers may help explain documented patterns of their species composition. We documented latitudinal geographic variation in plant palatability and plant–herbivore variation in species composition of the tettigoniid grass- interactions in Atlantic Coast salt marshes. Because it can be hopper fauna of Atlantic Coast salt marshes. Tettigoniids difficult to identify tettigoniids to species, we present a guide (N=740 adults) were collected from the Spartina alterni- to aid future workers in identifying the tettigoniid species flora zone of 31 salt marsh sites across a latitudinal range of common in these marshes. 13.19° (Florida to Maine), with an additional 52 individuals collected from the Juncus roemerianus zone of low-latitude Keywords Biogeography. Latitude . marshes for comparative purposes. Eight species were Plant–herbivore interactions . Bergmann’s rule . collected, but some were common only at a few sites or Orthoptera . Spartina alterniflora . Salt marsh rare throughout the entire collection range. The tettigoniid community was dominated by Orchelimum fidicinium at low latitudes and Conocephalus spartinae at high latitudes. Introduction Several factors might explain this shift, including changes in climate, plant phenology, and plant zonation patterns. -

Lepidoptera: Noctuidae

Life: The Excitement of Biology 5(2) 115 Orchelimum gladiator Bruner, 1891: An Addition to the Prey Record of the Great Black Wasp, Sphex pensylvanicus Linnaeus, 1763 (Hymenoptera: Sphecidae: Sphecinae)1 G. K. Lechner2 The Great Black Wasp, Sphex pensylvanicus Linnaeus, 1763 is a known predator of katydids (Orthoptera: Tettigoniidae) and is rather catholic in its choice of prey seemingly taking any katydid species available. In a previous paper (Lechner 2016), I stated that five species placed in four genera of katydids have been reported as prey items of S. pensylvanicus. Also, I reported four confirmed katydid species that I took from S. pensylvanicus that nest in the soil behind a vertical retaining wall on my residential property in Sioux City, Iowa. Herein, I add the Gladiator Meadow Katydid, Orchelimum gladiator Bruner, 1891 (Figures 1 and 2, next page), to the prey record of S. pensylvanicus. I took this paralyzed katydid from its captor female S. pensylvanicus on 28 August 2017. At that time, the wasp was attempting to enter her nest with her prey item in the north lot line retaining wall. Acknowledgments Many thanks to Dr. Thomas J. Walker (University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, USA) for identifying the specimen of Orchcelimum gladiator. This katydid was donated to the Ensiferan Collection at the University of Florida. Literature Cited Lechner, G. K. 2016. Interesting incidents with Sphex pensylvanicus Linnaeus, 1763 (Hymenoptera: Sphecidae) wasps and their prey items in Sioux City, Iowa, U.S.A. Life: The Excitement of Biology 4:27-31. https://blaypublishers.files.wordpress.com/2016/07/lechner-leb-41-interesting- incidents-with-sphex-pensylvanicus-linnaeus.pdf 1 Received on October 17, 2017. -

Orthoptera: Tettigoniidae: Conocephalinae: Copiphorini)

THOMAS J. WALKERJournal of Orthoptera Research 2014, 23(1): 69-7369 A new North American species of Bucrates (Orthoptera: Tettigoniidae: Conocephalinae: Copiphorini) THOMAS J. WALKER Department of Entomology & Nematology, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA. Email: [email protected] Abstract Methods Bucrates weissmani n.sp. is known from four localities in southern Access to supporting materials (SM).—To improve access to the origi- Arizona. It is smaller and more slender than the other four species of nal data and the analyses that were undertaken for this paper, four Bucrates, making it superficially similar to the Central American copiphorine tables were composed and assigned to SM. These may be accessed Caulopsis cuspidata, but more fundamental features refute the notion that through hyperlinks in BioOne's "Full Text" and PDF digital versions. it belongs in Caulopsis rather than Bucrates. Four other species of Bucrates are known. Two of these, capitatus (De Geer) and clausus (Scudder), occur in sympatry in Central America and tropical South America; lanista Rehn is Collecting sites of specimens examined.—D.B. Weissman and Jeff Cole known only from southern Brazil; and malivolans (Scudder) is restricted to provided specimens of the new species from the five sites listed the southeastern United States. All are easily distinguished morphologically below. Unless within brackets, [.], the data are from labels on the and, for the three for which the songs are known, by their songs. Unlike the specimens. two other species of Bucrates for which the habitat is known, B. weissmani occurs on altitudinal islands at the edge of a desert. The calling song of B. -

Grasshopper,Katydid,Crickets of Eoa Species Common Name

GRASSHOPPER,KATYDID,CRICKETS OF EOA SPECIES COMMON NAME Allonemobius allardi Allards ground cricket Allonemobius fasciatus striped ground cricket Allonemobius maculatus spotted ground cricket Allonemobius tinnulus tinkling ground cricket Amblycorpha alexanderi clicker round-wing katydid Amblycorpha longinicta common virtuoso katydid Amblycorpha oblongifolia oblong-winged katydid Amblycorpha rotundifolia rattler round-winged katydid Arphia simplex Plains yellow-winged grasshopper Arphia sulphurea spring yellow-winged grasshopper Arphia xanthoptera autumn yellow-wing grasshopper Atlanticus americanus American sheildback Camptonotus carlinensis Carolina leaf roller Ceuthophilus brevipes short-legged camel cricket Ceuthophilus g. gracilipes camel cricket Ceuthophilus uhleri Uhler's camel cricket Chortophaga viridifasciata N. green-striped hopper Conocephalus attenuatus long-tailed meadow katydid Conocephalus brevipennis short-winged meadow katydid Conocephalus fasciatus slender meadow katydid Conocephalus nemoralis woodland meadow katydid Dicromorpha viridis short-wing green grasshopper Dissosteira carolina Carolina grasshopper Ellipes minutus minute pygmy mole grasshopper Encoptolophus soridus dusky grasshopper Gryllus pennsylvanicus fall field cricket Melanolplus obovatipennis obovate-winged grasshopper Melanoplus bivittatus two-striped grasshopper Melanoplus differentialis differential grasshopper Melanoplus femurrubrum red-legged grasshopper Melanoplus gracilis graceful grasshopper Melanoplus keeleri luridus Keelers grasshopper Melanoplus -

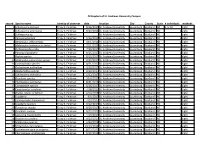

Orthoptera of St. Andrews University Campus Record Species Name

Orthoptera of St. Andrews University Campus record Species name Identity of observer date location City County State # individuals methods 1 Schistocerca obscura Tracy S. Feldman 8/16/2017 St. Andrews University Laurinburg Scotland NC 5 or 10 sight 2 Schistocerca americana Tracy S. Feldman 9/23/2014 St. Andrews University Laurinburg Scotland NC 5 sight 3 Schistocerca sp. Tracy S. Feldman St. Andrews University Laurinburg Scotland NC sight 4 Paroxya atlantica Tracy S. Feldman 9/16/2014 St. Andrews University Laurinburg Scotland NC 1 sight 5 Melanoplus differentialis Tracy S. Feldman 10/1/2014 St. Andrews University Laurinburg Scotland NC 1 sight 6 Melanoplus bivittatus or keeleri Tracy S. Feldman 7/21/2015 St. Andrews University Laurinburg Scotland NC 1 sight 7 Dichromorpha viridis Tracy S. Feldman 7/20/2017 St. Andrews University Laurinburg Scotland NC 1 sight 8 Paroxya clavuligera Tracy S. Feldman 8/15/2017 St. Andrews University Laurinburg Scotland NC 1 sight 9 Arphia species Tracy S. Feldman 8/15/2017 St. Andrews University Laurinburg Scotland NC 1 sight 10 Melanoplus sanguinipes group Tracy S. Feldman 9/20/2017 St. Andrews University Laurinburg Scotland NC 1 sight 11 Conocephalus species Tracy S. Feldman 8/21/2017 St. Andrews University Laurinburg Scotland NC 1 sight 12 Orchelimum pulchellum Tracy S. Feldman 9/20/2017 St. Andrews University Laurinburg Scotland NC 1 sight 13 Allonemobius species Tracy S. Feldman 9/20/2017 St. Andrews University Laurinburg Scotland NC 1 sight 14 Schistocerca damnifica Tracy S. Feldman 4/12/2017 St. Andrews University Laurinburg Scotland NC 1 sight 15 Orocharis species Tracy S. -

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Animal Species of North Carolina 2020

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Animal Species of North Carolina 2020 Hickory Nut Gorge Green Salamander (Aneides caryaensis) Photo by Austin Patton 2014 Compiled by Judith Ratcliffe, Zoologist North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources www.ncnhp.org C ur Alleghany rit Ashe Northampton Gates C uc Surry am k Stokes P d Rockingham Caswell Person Vance Warren a e P s n Hertford e qu Chowan r Granville q ot ui a Mountains Watauga Halifax m nk an Wilkes Yadkin s Mitchell Avery Forsyth Orange Guilford Franklin Bertie Alamance Durham Nash Yancey Alexander Madison Caldwell Davie Edgecombe Washington Tyrrell Iredell Martin Dare Burke Davidson Wake McDowell Randolph Chatham Wilson Buncombe Catawba Rowan Beaufort Haywood Pitt Swain Hyde Lee Lincoln Greene Rutherford Johnston Graham Henderson Jackson Cabarrus Montgomery Harnett Cleveland Wayne Polk Gaston Stanly Cherokee Macon Transylvania Lenoir Mecklenburg Moore Clay Pamlico Hoke Union d Cumberland Jones Anson on Sampson hm Duplin ic Craven Piedmont R nd tla Onslow Carteret co S Robeson Bladen Pender Sandhills Columbus New Hanover Tidewater Coastal Plain Brunswick THE COUNTIES AND PHYSIOGRAPHIC PROVINCES OF NORTH CAROLINA Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Animal Species of North Carolina 2020 Compiled by Judith Ratcliffe, Zoologist North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources Raleigh, NC 27699-1651 www.ncnhp.org This list is dynamic and is revised frequently as new data become available. New species are added to the list, and others are dropped from the list as appropriate. The list is published periodically, generally every two years. -

Orchelimum Superbum (Orthoptera: Tettigoniidae: Conocephalinae) on the Great Plains of North America

J.A. COLE AND W. CHATFIELD-TAYLORJournal of Orthoptera Research 2012, 21(1): 45-5045 Orchelimum superbum (Orthoptera: Tettigoniidae: Conocephalinae) on the Great Plains of North America JEFFREY A. COLE AND WILL CHATFIELD-TAYLOR [JAC] Entomology Section, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Los Angeles, California, USA. Email: [email protected] [WC-T] Department of Environmental Studies, University of Kansas, Kansas, USA. Abstract all known Orchelimum species (Capinera et al. 2004, Rehn & Hebard 1915, Walker 2011). Therefore, to test this hypothesis, we compared The meadow katydid Orchelimum superbum was previously known from scattered localities along the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts of North America. We morphology of the male terminalia and body size measurements found this species to be widespread and locally common on the Great Plains between specimens from the Great Plains and specimens that repre- in a variety of habitats, including tallgrass prairie, wetlands, and roadsides. sent "true" O. superbum from coastal localities within the historical We found no evidence for cryptic species after studying the morphology of range. the male terminalia, comparing body size, and analyzing 14 calling song The few Orchelimum species that are not readily separated by characters. Individuals from the Great Plains are consistently larger in body morphology are diagnosed by behavioral and ecological characters size than individuals from the historical range. From patterns of body size (Thomas & Alexander 1962). To test whether Great Plains O. super- variation and abundance, we hypothesize that the eastern Great Plains is bum represent a morphologically cryptic species, we undertook an the center of distribution for O. superbum and that the coastal localities, analysis of calling songs. -

1 the RESTRUCTURING of ARTHROPOD TROPHIC RELATIONSHIPS in RESPONSE to PLANT INVASION by Adam B. Mitchell a Dissertation Submitt

THE RESTRUCTURING OF ARTHROPOD TROPHIC RELATIONSHIPS IN RESPONSE TO PLANT INVASION by Adam B. Mitchell 1 A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Entomology and Wildlife Ecology Winter 2019 © Adam B. Mitchell All Rights Reserved THE RESTRUCTURING OF ARTHROPOD TROPHIC RELATIONSHIPS IN RESPONSE TO PLANT INVASION by Adam B. Mitchell Approved: ______________________________________________________ Jacob L. Bowman, Ph.D. Chair of the Department of Entomology and Wildlife Ecology Approved: ______________________________________________________ Mark W. Rieger, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources Approved: ______________________________________________________ Douglas J. Doren, Ph.D. Interim Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: ______________________________________________________ Douglas W. Tallamy, Ph.D. Professor in charge of dissertation I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: ______________________________________________________ Charles R. Bartlett, Ph.D. Member of dissertation committee I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: ______________________________________________________ Jeffery J. Buler, Ph.D. Member of dissertation committee I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. -

Dissertation No Endnote Codes

Regulation of community structure: top-down effects are modified by omnivory, nutrients, stress, and habitat complexity An Abstract of a Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Computer Science University of Houston In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy By Juan Manuel Jiménez Martínez May 2008 1 Abstract Biological communities are structured by a complex set of processes that have hindered the development of a general theory of community structure regulation. Current ideas and hypotheses have largely ignored the presence of interactions among the factors that regulate community structure. In this thesis I focused explicitly on the interactions among omnivory, nutrient availability, salinity stress levels, and habitat complexity. I examined these interactions using a combination of mesocosm and field factorial experiments in which I manipulated the levels of nutrients, salinity stress, and the presence (or absence) of top omnivores and common herbivores. These experiments demonstrated that, (1), nutrient addition increases the strength of top-down forces, but the effects of salinity stress are variable and species dependent, and (2), decreasing habitat complexity increases the strength of top-down forces and trophic cascades. In sum, my results suggest that the inherent complexity of natural communities and the interactions among the forces structuring them can lead to many different experimental outcomes that reflect the many ways in which species interactions are affected by environmental variables to alter the structure of these communities. Progress in understanding community structure will come from experiments that probe these interactive processes and seek to identify commonalities in responses based on consumer behavior, plant traits or habitat type. -

Katydids Katydids Are a Large Group of Insects in the Order Orthoptera, Related to the Grasshoppers and Crickets

A Horticulture Information article from the Wisconsin Master Gardener website, posted 25 Sept 2017 Katydids Katydids are a large group of insects in the order Orthoptera, related to the grasshoppers and crickets. Some katydids have been called long-horned grasshoppers because of their long and slender shape, but actually katydids are more closely related to crickets than to any type of grasshopper. There are about 6,400 species worldwide, with the greatest diversity in the tropics. Their classifi cation is not well established, with taxonomists differing in their classifi cation schemes. Most North American species are placed in the family Tettigoniidae and divided among seven to ten subfamilies. The main groups of commonly encountered katydids include the true katydids (Pseudophyllinae), false The greater angle-wing (Microcentrum katydids (Phaneropterinae), shield-backed katydids (Tettigoniinae rhombifolium) is a leaf mimic katydid. – but sometimes divided into three subfamilies), meadow katydids (Conocephalinae) and coneheaded katydids (Copiphorinae, but sometimes these are included with the meadow katydids). There are about 255 species in North American and 20 species in the Midwest. Tropical katydids in Costa Rica (L and LC, lichen katydid, Markia hysterix, in Costa Rica (C), and katydids in Peruvian Amazon (RC and R). Katydids are usually green and camoufl aged to blend in with foliage, more commonly heard than seen. They have a body taller than it is wide and thin and hind legs that are longer than the other pairs of legs. Some characteristics that distinguish katydids from other orthopterans include having the wings held vertically over body (like a roof of a house), hearing organs on the front tibia, all tarsi with 4 segments (crickets have 3), a typically fl attened and sword-like ovipositor, and very long, thin antennae as long as Black-legged meadow katydid or longer (Orchelimum nigripes). -

SGCN Summaries

Appendix 3 - SGCN Summaries Michigan’s Wildlife Action Plan 2015-2025 Cover Photos Credits Habitat – MNFI, Dave Cuthrell Eastern Massasauga – Jennifer Moore MICHIGAN’S WILDLIFE ACTION PLAN 2015-2025 SGCN DISTRIBUTION, STATUS, HABITATS & THREATS TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION TO SGCN SUMMARIES .................................................................................................................. 2 SGCN SUMMARIES ................................................................................................................................................. 3 MUSSELS ................................................................................................................................................................... 6 SNAILS ..................................................................................................................................................................... 26 CRAYFISH ................................................................................................................................................................. 57 INSECTS ................................................................................................................................................................... 59 MAYFLIES ............................................................................................................................................................ 60 DRAGONFLIES & DAMSELFLIES .........................................................................................................................