RSI June 2019 Volume XI Number 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Full Article

SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT UDC 316.35(470.12) © Gulin K.A. © Dementieva I.N. Protest sentiments of the region’s population in crisis One form of social protest is the protest sentiments of the population, i.e., the expression of extreme dissatisfaction with their position in the current situation. In the present paper we make an attempt to trace the dynamics of protest potential in the region, draw a social portrait of the inhabitants of the region prone to protest behavior, identify the most important factors determining the formation of a latent protest activity, and identify the causes of the relative stability of protest potential in the region during the economic crisis. The study was conducted on the basis of statistics and results of regular monitoring held by ISEDT RAS in the Vologda region. Social conflict, protest behavior, protest potential, community, monitoring, social management, public opinion, crisis, socio-economic situation. Konstantin A. GULIN Ph.D. in History, Deputy Director of ISEDT RAS [email protected] Irina N. DEMENTIEVA Junior scientific associate of ISEDT RAS [email protected] In the contradictory trends in the socio- One form of conflict expressions is social economic development of territories and the protest. The concept of “social protest” in modern sociological literature covers a rather population’s material welfare, the issue of wide range of phenomena. In its most general socio-psychological climate in society, the form protest means “strong objection to escalation of internal contradictions and anything, a statement of disagreement with conflicts is being updated. anything, the reluctance of something” [1]. 46 3 (15) 2011 Economical and social changes: facts, trends, forecast SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT K.A. -

The Economics of the Nord Stream Pipeline System

The Economics of the Nord Stream Pipeline System Chi Kong Chyong, Pierre Noël and David M. Reiner September 2010 CWPE 1051 & EPRG 1026 The Economics of the Nord Stream Pipeline System EPRG Working Paper 1026 Cambridge Working Paper in Economics 1051 Chi Kong Chyong, Pierre Noёl and David M. Reiner Abstract We calculate the total cost of building Nord Stream and compare its levelised unit transportation cost with the existing options to transport Russian gas to western Europe. We find that the unit cost of shipping through Nord Stream is clearly lower than using the Ukrainian route and is only slightly above shipping through the Yamal-Europe pipeline. Using a large-scale gas simulation model we find a positive economic value for Nord Stream under various scenarios of demand for Russian gas in Europe. We disaggregate the value of Nord Stream into project economics (cost advantage), strategic value (impact on Ukraine’s transit fee) and security of supply value (insurance against disruption of the Ukrainian transit corridor). The economic fundamentals account for the bulk of Nord Stream’s positive value in all our scenarios. Keywords Nord Stream, Russia, Europe, Ukraine, Natural gas, Pipeline, Gazprom JEL Classification L95, H43, C63 Contact [email protected] Publication September 2010 EPRG WORKING PAPER Financial Support ESRC TSEC 3 www.eprg.group.cam.ac.uk The Economics of the Nord Stream Pipeline System1 Chi Kong Chyong* Electricity Policy Research Group (EPRG), Judge Business School, University of Cambridge (PhD Candidate) Pierre Noёl EPRG, Judge Business School, University of Cambridge David M. Reiner EPRG, Judge Business School, University of Cambridge 1. -

ACC JOURNAL 2020, Volume 26, Issue 2 DOI: 10.15240/Tul/004/2020-2-002

ACC JOURNAL 2020, Volume 26, Issue 2 DOI: 10.15240/tul/004/2020-2-002 THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE NONPROFIT SECTOR IN RUSSIAN REGIONS: MAIN CHALLENGES Anna Artamonova Vologda Research Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Department of Editorial-and-Publishing Activity and Science-Information Support, 56A, Gorky str., 160014, Vologda, Russia e-mail: [email protected] Abstract This article aims at identifying the main barriers hindering development of the nonprofit sector in Russian regions. The research is based on the conviction that the development of the nonprofit sector is crucial for the regional socio-economic system and depends upon civic engagement. The results of an analysis of available statistical data and a sociological survey conducted in one of the Russian regions reveal that the share of the Russians engaged in volunteer activities is low; over 80% of the population do not participate in public activities; less than 10% have definite knowledge of working nonprofit organizations. The study allowed identifying three groups of the main barriers and formulating some recommendations for their overcoming. Keywords Russia; Nonprofit sector; Nongovernmental organization; Civic participation; Civic engagement. Introduction Sustainable development of Russian regions requires the fullest use of their internal potential. As the public and private sectors cannot meet all demands concerning the provision of high living standards for all groups of the population, it is necessary for local authorities to find new opportunities for effective and mutually beneficial cooperation with other economic actors. In Russian regions, in this regard a new trend becomes evident government starts to pay more attention to organizations of the third (nonprofit) sector. -

Gazprom in Figures 2007–2011 Factbook Gazprom in Figures 2007–2011

REACHING NEW HORIZONS GAZPROM IN FIGURES 2007–2011 FACTBOOK GAZPROM IN FIGURES 2007–2011. FACTBOOK OAO GAZPROM TABLE OF CONTENTS Gazprom in Russian and global energy industry 3 Macroeconomic Data 4 Market Data 5 Reserves 7 Licenses 16 Production 18 Geological exploration, production drilling and production capacity in Russia 23 Geologic search, exploration and production abroad 26 Promising fields in Russia 41 Transportation 45 Gas transportation projects 47 Underground gas storage 51 Processing of hydrocarbons and production of refined products 55 Electric power and heat generation 59 Gas sales 60 Sales of crude oil, gas condensate and refined products 64 Sales of electricity and heat energy, gas transportation sales 66 Environmental measures, energy saving, research and development 68 Personnel 70 Convertion table 72 Glossary of basic terms and abbreviations 73 Preface Factbook “Gazprom in Figures 2007–2011” is an informational and statistical edition, prepared for OAO Gazprom annual General shareholders meeting 2012. The Factbook is prepared on the basis of corporate reports of OAO Gazprom, as well as on the basis of Russian and foreign sources of publicly disclosed information. In the present Factbook, the term OAO Gazprom refers to the head company of the Group, i.e. to Open Joint Stock Company Gazprom. The Gazprom Group, the Group or Gazprom imply OAO Gazprom and its subsidiaries taken as a whole. For the purposes of the Factbook, the list of subsidiaries was prepared on the basis used in the preparation of OAO Gazprom’s combined ac- counting (financial) statements in accordance with the requirements of the Russian legislation. Similarly, the terms Gazprom Neft Group and Gazprom Neft refer to OAO Gazprom Neft and its subsidiaries. -

Science of Economics

ACC JOURNAL XXVI 2/2020 Issue B Science of Economics TECHNICKÁ UNIVERZITA V LIBERCI HOCHSCHULE ZITTAU/GÖRLITZ INTERNATIONALES HOCHSCHULINSTITUT ZITTAU (TU DRESDEN) UNIWERSYTET EKONOMICZNY WE WROCŁAWIU WYDZIAŁ EKONOMII, ZARZĄDZANIA I TURYSTYKI W JELENIEJ GÓRZE Indexed in: Liberec – Zittau/Görlitz – Wrocław/Jelenia Góra © Technická univerzita v Liberci 2020 ISSN 1803-9782 (Print) ISSN 2571-0613 (Online) ACC JOURNAL je mezinárodní vědecký časopis, jehož vydavatelem je Technická univerzita v Liberci. Na jeho tvorbě se podílí čtyři vysoké školy sdružené v Akademickém koordinačním středisku v Euroregionu Nisa (ACC). Ročně vycházejí zpravidla tři čísla. ACC JOURNAL je periodikum publikující původní recenzované vědecké práce, vědecké studie, příspěvky ke konferencím a výzkumným projektům. První číslo obsahuje příspěvky zaměřené na oblast přírodních věd a techniky, druhé číslo je zaměřeno na oblast ekonomie, třetí číslo pojednává o tématech ze společenských věd. ACC JOURNAL má charakter recenzovaného časopisu. Jeho vydání navazuje na sborník „Vědecká pojednání“, který vycházel v letech 1995-2008. ACC JOURNAL is an international scientific journal. It is published by the Technical University of Liberec. Four universities united in the Academic Coordination Centre in the Euroregion Nisa participate in its production. There are usually three issues of the journal annually. ACC JOURNAL is a periodical publishing original reviewed scientific papers, scientific studies, papers presented at conferences, and findings of research projects. The first issue focuses on natural sciences and technology, the second issue deals with the science of economics, and the third issue contains findings from the area of social sciences. ACC JOURNAL is a reviewed one. It is building upon the tradition of the “Scientific Treatises” published between 1995 and 2008. -

Doi 10.23859/2587-8344-2019-3-1-2 Удк 94 (470.12).083

RESEARCH http://en.hpchsu.ru DOI 10.23859/2587-8344-2019-3-1-2 УДК 94 (470.12).083 Коновалов Федор Яковлевич Кандидат исторических наук, доцент, Научно-издательский центр «Древности Севера» (Вологда, Россия) [email protected] Konovalov Fedor Candidate of Historical Sciences, Associate Professor, Scientific and Publishing Centre ‘Antiquities of the North’ (Vologda, Russia) [email protected] Секретная агентура провинциальных губернских жандармских управлений в начале XX в. (на материалах Вологодского губернского жандармского управления)*1 Secret Agency of the Provincial Gendarmerie at the Beginning of the 20th Century (on the Materials of the Vologda Provincial Gendarme Department) Аннотация. Эффективная деятельность политического сыска царской России в начале XX в. была невозможна без использования секретной агентуры как главного источника ин- формации о противниках режима. Это было осознано как на уровне руководства Департа- мента полиции, так и органов, ведущих розыскную работу на местах, – губернских жандарм- ских управлений (ГЖУ). В статье рассматривается деятельность Вологодского ГЖУ по соз- данию сети осведомителей в рядах революционных групп и ссыльных на территории губер- нии, оценивается количественный и качественный состав данной сети. Результатом данной работы стало почти полное пресечение всяких попыток активности в рядах противников ца- * 1Для цитирования: Коновалов Ф.Я. Секретная агентура провинциальных губернских жандармских управлений в начале XX в. (на материалах Вологодского губернского жан- дармского управления // Historia Provinciae – Журнал региональной истории. 2019. Т. 3. № 1. С. 86–145. DOI: 10.23859/2587-8344-2019-3-1-2 For citation: Konovalov, F. Secret Agency of the Provincial Gendarmerie at the Beginning of the 20th Century (on the Materials of the Vologda Provincial Gendarme Department). Historia Provinciae – The Journal of Regional History, vol. -

Greece Announces Major Arms Purchase

Greece announces major arms purchase As Mr Mitsotakis said at the TIF (Thessaloniki International Fair which is not being held this year due to the pandemic, but the venue as a podium for political declarations was kept).: “In recent years, the defense sector has experienced conditions of disinvestment, after a period of high costs and not always targeted armaments procurements. Well, it's time to balance needs and opportunities. It is time to strengthen the Armed Forces as a legacy for the security of the country, but also as the highest obligation to the Greeks who will bear the cost. It is the price of our place on the map. Today, therefore, I am announcing six emblematic decisions that multiply the power, functionality and effectiveness of Greek weapons.” The six decisions announced by PM Mitsotakis: 1. The Hellenic Air Force will immediately acquires a squadron of 18 Rafale fighter jets that will replace older Mirage 2000 fighters. As the Greek PM said these are fourth generation superior aircraft that “strengthen Greek deterrent power... in combination with the modernized F-16” 2. The Hellenic Navy is launching the process for the procurement of four new multi-role frigates, while at the same time, it will modernize and upgrade four existing MEKO frigates. Mr Mitsotakis left open, what these ships will be, and several countries are looking at the tender for their own shipyards, or design bureaus. The new ships will also be accompanied by four MH-60R (Romeo) naval helicopters. 3. The arsenal of the three branches is being enriched as a whole. -

To Nmrs at SHAPE

Greek Military In ordet to become familiar with the Hellenic the Armed Forces, you can have a look to the Command Structure as it is shown on the slide below. Command Structure Gr. Police ΧΧΧΧΧ Coast Guard (2) HNDGS (2) ΧΧΧΧ HAGS-HNGS-HAFGS C.A.A Civil Aviation.Admin (3) (2) Fire Dep. JORRHQ OTHER COMMANDS (1) (3) ΧΧΧΧ ΧΧΧΧ ΧΧΧΧ ΧΧΧ ΧΧΧ 1st ARMY/ FLEET TACTICAL B΄CORPS HMCII OHQs-EU COMMAND AIR FORCE ΧΧΧ COMMAND A΄ CORPS ΧΧΧ LEGEND D΄CORPS (1) Operational Command ΧΧΧ (2) Operational Command war-crisis C΄CORPS/ (3) Administrative Control NDC-GR In specifics: a. At Strategic Level, Operational Command is laid with the CHOD, supported by the General staffs of the three Services b. At Operational Level there are “7” major HQs and the NDC-GR which is assigned to NATO as FLR HQ. c. In addition there is Joint HQ for Rapid Response operations at Tactical Level. d. In case of open hostilities the CHOD assumes Operational Command, of Police, Coast Guard, Border Police and the Fire Department Furthermore, The Strategic Military Objectives and the Main Operational Tasks, as defined by the National Defence Strategy, can be summarized as: a. Firstly, maintaining and further developing our ability to deter and should deterrence fails to defend against any kind of external threat, preserving the national sovereignty and territorial integrity. b. Secondly, to promote regional and global Security & Stability, contributing to Crisis Management and to defence against asymmetric threats, enhancing military cooperation, maintaining regional presence, participating to international peace support operations and contributing to the development and implementation of confidence building measures. -

Diaspora Greeks Will Shape Greece's Future Archbishop Refusing To

O C V ΓΡΑΦΕΙ ΤΗΝ ΙΣΤΟΡΙΑ Bringing the news ΤΟΥ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΜΟΥ to generations of ΑΠΟ ΤΟ 1915 The National Herald Greek Americans A WEEKLY GREEK AMERICAN PUBLICATION c v www.thenationalherald.com VOL. 10, ISSUE 493 March 24, 2007 $1.00 GREECE: 1.75 EURO Diaspora Greeks Will Shape Greece’s Future Dora discusses issues ahead of her stateside Visit, meets with Ban, Rice and other officials By Aris Papadopoulos Special to the National Herald ATHENS – By enacting legislation allowing Greeks who live abroad to vote in Greek national elections, the Government has fulfilled an obliga- tion to Greeks of the Diaspora, For- eign Minister Dora Bakoyanni told the National Herald, adding that Greeks residing outside the geo- graphic borders of the Hellenic Re- public will “now have a hand in shaping the country’s future.” Speaking to the Herald shortly before her visit to New York this week, Mrs. Bakoyanni said, “This is a very significant initiative adopted by the New Democracy Government. The Greek Government is fulfilling a very large obligation to Greeks living abroad. Through this initiative, the Government is enabling them to equally participate in the most im- portant part of the democratic Foreign Minister Dora Bakoyanni process – elections – by allowing The Spirit of Greek Independence: “We would rather die…” them to mail in their ballots. This tion; and coordinate our efforts for way, they can play a role in shaping every issue concerning Hellenes French artist Claude Pinet’s famous painting, “Dance of Zalongo.” The Souliotisses were women from the mountainous area of Souli in Epiros. -

The Question of Northern Epirus at the Peace Conference

Publication No, 1. THE QUESTION OF NORTHERN EPIRUS AT THE PEACE CONFERENCE BY NICHOLAS J. CASSAVETES Honorary Secretary of the Pan-Epirotie Union of America BMTKB BY CAEEOLL N. BROWN, PH.D. *v PUBLISHED FOR THE PAN-EPIROTIC UNION OF AMERICA ? WâTBB STREET, BOSTOH, MASS. BY OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS AMERICAN BRANCH 85 WEST 32ND S1REET, NEW YÛHK 1919 THE PAN-EPIROTIC UNION OF AMERICA GENERAL COUNCIL Honorary President George Christ Zographos ( Ex-president of the Autonomous State of Epirus and formes Minister of Foreign Affairs of Greece) Honorary Secretary Nicholas J. Cassavetes President Vassilios K. Meliones Vice-President Sophocles Hadjiyannis Treasurer George Geromtakis General Secretary Michael 0. Mihailidis Assistant Secretary Evangelos Despotes CENTRAL OFFICE, ? Water Street, Room 4Î0, BOSTON, MASS. THE QUESTION OF NORTHERN EPIRUS AT THE PEACE CONFERENCE BY NICHOLAS J. CASSAVETES Honorary Secretary of the Pan-Bpirotic Union of America EDITED BY CARROLL N. BROWN, PH.D. PUBLISHED FOR THE PAN-EPIROTIC UNION OF AMERICA 7 WATER STREET, BOSTON, MASS. BY OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS AMERICAN BRANCH 85 WEST 82ND STREET, NEW YORK 1919 COPYIUQHT 1919 BY THE OXFORD UNIVERSITY PKKSS AMERICAN BRANCH PREFACE Though the question of Northern Epirus is not pre eminent among the numerous questions which have arisen since the political waters of Europe were set into violent motion by the War, its importance can be measured neither by the numbers of the people involved, nor by the serious ness of the dangers that may arise from the disagreement of the two or three nations concerned in the dispute. Northern Epirus is the smallest of the disputed territories in Europe, and its population is not more than 300,000. -

Atlas of High Conservation Value Areas, and Analysis of Gaps and Representativeness of the Protected Area Network in Northwest R

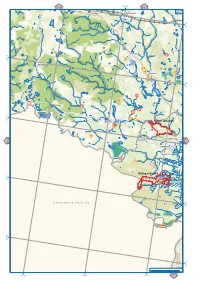

34°40' 216 217 Chudtsy Efimovsky 237 59°30' 59°20' Anisimovo Loshchinka River Somino Tushemelka River 59°20' Chagoda River Golovkovo Ostnitsy Spirovo 59°10' Klimovo Padun zakaznik Smordomsky 238 Puchkino 236 Ushakovo Ignashino Rattsa zakaznik 59°0' Rattsa River N O V G O R O D R E G I O N 59°0' 58°50' °50' 58 0369 км 34°20' 34°40' 35°0' 251 35°0' 35°20' 217 218 Glubotskoye Belaya Velga 238 protected mire protected mire Podgornoye Zaborye 59°30' Duplishche protected mire Smorodinka Volkhovo zakaznik protected mire Lid River °30' 59 Klopinino Mountain Stone protected mire (Kamennaya Gora) nature monument 59°20' BABAEVO Turgosh Vnina River °20' 59 Chadogoshchensky zakaznik Seredka 239 Pervomaisky 237 Planned nature monument Chagoda CHAGODA River and Pes River shores Gorkovvskoye protected mire Klavdinsky zakaznik SAZONOVO 59°10' Vnina Zalozno Staroye Ogarevo Chagodoshcha River Bortnikovo Kabozha Pustyn 59°0' Lake Chaikino nature monument Izbouishchi Zubovo Privorot Mishino °0' Pokrovskoye 59 Dolotskoye Kishkino Makhovo Novaya Planned nature monument Remenevo Kobozha / Anishino Chernoozersky Babushkino Malakhovskoye protected mire Kobozha River Shadrino Kotovo protected Chikusovo Kobozha mire zakazhik 58°50' Malakhovskoye / Kobozha 0369 protected mire км 35°20' 251 35°40' 36°0' 252 36°0' 36°20' 36°40' 218 219 239 Duplishche protected mire Kharinsky Lake Bolshoe-Volkovo zakaznik nature monument Planned nature monument Linden Alley 59°30' Pine forest Sudsky, °30' nature monument 59 Klyuchi zakaznik BABAEVO абаево Great Mosses Maza River 59°20' -

The Historical Review/La Revue Historique

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by National Documentation Centre - EKT journals The Historical Review/La Revue Historique Vol. 11, 2014 Index Hatzopoulos Marios https://doi.org/10.12681/hr.339 Copyright © 2014 To cite this article: Hatzopoulos, M. (2014). Index. The Historical Review/La Revue Historique, 11, I-XCII. doi:https://doi.org/10.12681/hr.339 http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 21/02/2020 08:44:40 | INDEX, VOLUMES I-X Compiled by / Compilé par Marios Hatzopoulos http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 21/02/2020 08:44:40 | http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 21/02/2020 08:44:40 | INDEX Aachen (Congress of) X/161 Académie des Inscriptions et Belles- Abadan IX/215-216 Lettres, Paris II/67, 71, 109; III/178; Abbott (family) VI/130, 132, 138-139, V/79; VI/54, 65, 71, 107; IX/174-176 141, 143, 146-147, 149 Académie des Sciences, Inscriptions et Abbott, Annetta VI/130, 142, 144-145, Belles-Lettres de Toulouse VI/54 147-150 Academy of France I/224; V/69, 79 Abbott, Bartolomew Edward VI/129- Acciajuoli (family) IX/29 132, 136-138, 140-157 Acciajuoli, Lapa IX/29 Abbott, Canella-Maria VI/130, 145, 147- Acciarello VII/271 150 Achaia I/266; X/306 Abbott, Caroline Sarah VI/149-150 Achilles I/64 Abbott, George Frederic (the elder) VI/130 Acropolis II/70; III/69; VIII/87 Abbott, George Frederic (the younger) Acton, John VII/110 VI/130, 136, 138-139, 141-150, 155 Adam (biblical person) IX/26 Abbott, George VI/130 Adams,