Olpcworkshop for Education Officers Workbook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Linux Sound Subsystem Documentation Release 4.13.0-Rc4+

Linux Sound Subsystem Documentation Release 4.13.0-rc4+ The kernel development community Sep 05, 2017 CONTENTS 1 ALSA Kernel API Documentation 1 1.1 The ALSA Driver API ............................................ 1 1.2 Writing an ALSA Driver ........................................... 89 2 Designs and Implementations 145 2.1 Standard ALSA Control Names ...................................... 145 2.2 ALSA PCM channel-mapping API ..................................... 147 2.3 ALSA Compress-Offload API ........................................ 149 2.4 ALSA PCM Timestamping ......................................... 152 2.5 ALSA Jack Controls ............................................. 155 2.6 Tracepoints in ALSA ............................................ 156 2.7 Proc Files of ALSA Drivers ......................................... 158 2.8 Notes on Power-Saving Mode ....................................... 161 2.9 Notes on Kernel OSS-Emulation ..................................... 161 2.10 OSS Sequencer Emulation on ALSA ................................... 165 3 ALSA SoC Layer 171 3.1 ALSA SoC Layer Overview ......................................... 171 3.2 ASoC Codec Class Driver ......................................... 172 3.3 ASoC Digital Audio Interface (DAI) .................................... 174 3.4 Dynamic Audio Power Management for Portable Devices ...................... 175 3.5 ASoC Platform Driver ............................................ 180 3.6 ASoC Machine Driver ............................................ 181 3.7 Audio Pops -

Investigating Choices of Appropriate Devices for One-To-One Computing Initiatives in Schools Worldwide

International Journal of Information and Education Technology, Vol. 6, No. 10, October 2016 Investigating Choices of Appropriate Devices for One-to-One Computing Initiatives in Schools Worldwide M. Sirajul Islam and Annika Andersson schools should be governed by “creating an environment in Abstract—The use of technology in schools is rapidly which the child will become highly involved in experience of increasing – today most notably through the one-to-one (1:1) a kind to provide rich soil for the growth in intuitions and programs that are being implemented all around the world. concepts for dealing with thinking, learning, playing, and so Considering how new technologies are emerging fast and obsoleting others in schools, there is a need to continuously on” [5]. In this direction, one of the first practical initiatives monitor and understand the features of various devices in terms on implementing constructionist learning for children with of embedded technology and interaction with users. This paper computers was the development of programming language therefore presents the nature of computing devices used in 1:1 called „Logo‟ in 1967. Following such initiatives, Alan C. computing programs in schools around the world, including Kay, who was closely associated with Papert for promoting investigating the benefits and drawbacks, by means of a and implementing computer based educational constructivism, systematic literature review and a survey conducted in some schools in Sweden. The paper also presents findings based on developed a laptop computer for children in 1970 based on how the various uses of technology affect cooperation practices the sketches of the KiddiComp called „Daynabook‟ as well as personal exploration. -

Meet the Eee PC

Chapter 1 Meet the Eee PC In This Chapter ▶ Not your average laptop ▶ Popular Eee PC misconceptions ▶ Reviewing Eee PC models ▶ Selecting an Eee PC ▶ Purchasing an Eee PC his chapter introduces you to the ASUS Eee PC. (Eee PC is pronounced Twith a single E, not multiple EEEs, as in “Eeek, a mouse!”) If you’re won- dering where all those Es came from, it’s from a marketing campaign that states the computer is “Easy to learn, easy to work, and easy to play.” In this chapter, I tell you what the Eee PC is — and just as important, what it isn’t. I then list available models, describe their specifications, and conclude by giving you tips on selecting and purchasing an Eee PC. Eee PC: Not Your Average Laptop The Eee PC (see Figure 1-1) has been called a mini-laptop, a subnotebook, a Mobile Internet Device (MID), and a netbook (a catchy marketing buzzword for small, Internet-centric laptops). Whatever you call it, the Eee PC is a shrunk- down, lightweightCOPYRIGHTED laptop that has these keyMATERIAL features: ✓ Small — At just a bit over two pounds and roughly the size of this book, the 7-inch and 8.9-inch screen models are designed to be go-anywhere, do-anything personal computers. To fit in such a small package, keys on the Eee PC are smaller than those found on a typical laptop keyboard — right around 83 percent of normal. After you get used to the small size it’s possible to touch type with some practice. -

ICT & Education Specialist the World Bank

People and Technology in World Class Education Systems News, perspectives and challenges from developing countries Michael Trucano Sr. ICT & Education Specialist The World Bank EMINENT Rome, Italy 4 December 2008 drawing on Lessons from the World Bank and the International Donor Community What we know and what we don’t about using technology in education in developing countries What we know and what we don’t about using technology effectively in education in developing countries (and how might this be relevant for Europe) ? “I believe that the Internet is destined to revolutionize our educational system and that in a few years it will supplant largely, if not entirely, the use of textbooks. It is possible to touch every branch of human knowledge through the Internet . “ I believe that the motion picture is destined to revolutionize our educational system and that in a few years it will supplant largely, if not entirely, the use of textbooks. It is possible to touch every branch of human knowledge through the motion picture . -- Thomas Edison 1922 ICTs in Education ICTS radio computers = information TV & Internet communication phones technologies devices photo opportunities or strategic choices for education reform ? Michael Trucano Sr. ICT & Education Specialist The World Bank helping the World Bank education sector and international donor community and ‘client countries’ “Get smart” @ appropriate relevant effective and, just as importantly… in appropriate ir relevant in effective uses of technologies to aid a variety of developmental objectives in the education sector What is the World Bank ? a global development institution owned by > 180 member countries with: – significant financial resources – an experienced, knowledgeable, and dedicated staff – convening power – experts in more than 100 countries. -

Leo2012f2linux.Pdf

1 2 Table of contents Title Page Chapter I - History of Linux…...............................................................5 GNU/Linux naming controversy...........................................9 Open Source and Linux Foundation....................................10 BSD License.......................................................................16 Costs.................................................................................18 Chapter II - Linux a multiuser system..................................................21 TTYs.................................................................................23. Group management..........................................................26 Virtual Machines...............................................................30 Chapter III - Installation and applications.............................................35 Linux Installation.............................................................36 Linux Distributions..........................................................37 Installation of applications...............................................42 Window managers and desktop environments..................47 Program equivalents........................................................51 3 Chapter IV – Connecting to Linux....................................................57 About Hardware..........................................................58 Connecting a device to the PC......................................60 Hardware compatibility and recognition.......................61 The kernel...................................................................64 -

The Charisma of One Laptop Per Child's XO Laptop in Paraguay

Preprint copy - to appear in: Eden Medina, Ivan da Costa Marques, and Christina Holmes (eds.), Beyond Imported Magic: Essays on Science, Technology, and Society in Latin America. MIT Press, 2014. 10 Translating Magic: The Charisma of One Laptop per Child’s XO Laptop in Paraguay Morgan G. Ames In April 2008 liberal candidate Fernando Lugo won the Paraguayan presidency with 41 percent of the vote. It was the first time Paraguay’s conservative Colorado party had relinquished power in sixty-one years and one of the few peaceful transfers of power between parties in the country’s nearly two-hundred-year history (Nickson 2009). Known by his supporters as the “Bishop of the Poor” for his humanitarian service as a Catholic priest in one of Paraguay’s poorest districts, Lugo centered his campaign on reducing the nation’s bleak social inequalities and widespread corruption (Economist 2008; Nickson 2009). Lugo’s messages of hope and reform lasted beyond his election. During my fieldwork in 2010, many told me about their newfound hopes for Paraguay’s future on the 369 Preprint copy - to appear in: Eden Medina, Ivan da Costa Marques, and Christina Holmes (eds.), Beyond Imported Magic: Essays on Science, Technology, and Society in Latin America. MIT Press, 2014. world stage, even as Lugo became embroiled in scandal and faltered in implementing the dramatic changes he had promised (Economist 2009; Prensa Internacional 2009). Also in 2008, two elite, well-connected Paraguayans, both fresh out of college (one from Tufts University in Massachusetts, one from the Catholic University in Asunción), took up the banner of hope and steered it toward education. -

The Impact on Formal Learning in Primary School Education Authors

One Year of One-to-one Computing in Sri Lanka – The Impact on Formal Learning in Primary School Education Authors: 1) Peter Mozelius1 2) Kalelur Rahuman2 3) G. N. Wikramanayake2 Affiliation: 1) Stockholm University, Sweden 2) University of Colombo, School of Computing, Sri Lanka Abstract: One-to-one computing has lately become a frequently used buzzword in the discussions on e-learning in primary education. The main idea in one-to-one computing is to provide every student with a personal computer. This has often been combined with Internet access and the idea to share content but not to share the computers. Some examples of low-cost laptop brands produced for one-to-one computing are Intel Classmate, Asus Eee PC and the One Laptop Per Child (OLPC) XO computer. Different versions of one-to-one computing concept have recently been implemented in the developing world as well as in several developing countries. This study will focus on the Sri Lankan OLPC initiative and data has been gathered from three selected primary schools. In the Sri Lankan OLPC model there is no focus on Internet connectivity and the emphasis is on content development in local languages. Schools chosen in this first one year pilot project are to be classified as to be “the poorest of the poor” and located in rural areas. The research question in this paper is, if and why the introduction of one-to-one computing has had an impact on the formal learning outcomes. Our measurements of the impact on the formal education results are based on data from the selected schools’ grading registries, but the general analysis and conclusions are also based on observations and interviews with teachers and school principals. -

The OLPC XO, Intel Classmate PC and Asus Eee PC User Study

The OLPC XO, Intel Classmate PC and Asus Eee PC user study Submitted in partial fulfilment Of the requirements of the degree of Bachelor of Science (Honours) Of Rhodes University Constance Sibanda Grahamstown, South Africa November 2009 i Abstract Information communication technologies (ICTs) are increasingly considered valuable tools in education, promoting higher cognitive processes and allowing teachers and learners access to a wealth of information. However, these technologies are not easily accessible in developing countries such as South Africa, where a large percentage of the population are poor and are said to live below the breadline. The recent creation of small, low cost and low powered laptops called netbooks, are seen as possible solutions to allow or promote the use and integration of ICTs in education in these disadvantaged communities. This project evaluates the intuitiveness of the OLPC XO, the Intel Classmate and the Asus Eee PC in the context of secondary school education through the use of a user study. The user study involved three teachers and three learners from local secondary schools in Grahamstown. The results of the user study revealed that the teachers and learners (on the whole) felt that the Intel Classmate is the most intuitive netbook for secondary school learners involved in the user study. The presence of the VGA port and the portable nature of the Asus Eee were noted by participants as advantageous. The Asus Eee was also found to be appropriate for secondary school education although it was criticised for its small screen, small keyboard and absence of a webcam. Participants felt that the OLPC XO is less intuitive for secondary school educational purposes and is better suited for small children. -

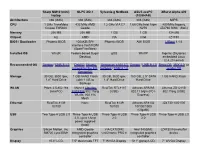

Sharp MM10 (Mini) Laptop OLPC XO-1 Sylvania G Netbook ASUS

Sharp MM10 (mini) OLPC XO-1 Sylvania g NetBook ASUS eeePC XBurst Alpha 400 laptop (1005HAB) Architecture x86 (i686) x86 (i586) x86 (i686) x86 (i686) MIPS CPU 1 GHz TransMeta 433 MHz AMD 1.2 GHz VIA C7 1.66 GHz Intel Atom 400 MHz Ingenic Crusoe TM5800 Geode N270 JZ4730 RISC (SoC) Memory 256 MB 256 MB 1 GB 1 GB 128 MB Chipset ALi AMD VIA Intel JZ4730 BIOS / Bootloader Phoenix BIOS 1024KiB SPI- Phoenix BIOS AMI BIOS U-Boot 1.1.6 interface flash ROM (OpenFirmWare) Installed OS Win2K Fedora-based Sugar gOS WinXP Ingenic (Skytone) Desktop embedded Linux (2.4.20 kernel) Recommended OS Gentoo / UNR 9.1.0 DebXO, Ubuntu Gentoo on a VIA C7 Gentoo / UNR 9.1.0 Retro-OS, 3MX 4.0, or Intrepid for the XO, Netbook / UNR 9.1.0 vendor OS GentooXO Storage 30 GB, 3600 rpm, 1 GB NAND Flash 30 GB, 3600 rpm, 160 GB, 2.5" SATA 1 GB NAND Flash 1.8" Hard Drive (with 1 GB ro 1.8" Hard Drive Hard Drive backup) WLAN Prism 2.5 802.11b Marvell Libertas RealTek RTL8187 Atheros AR9285 Atheros ZD1211B (miniPCI) 88W8388 802.11b/g (USB) 802.11 b/g/n (PCI- 802.11b/g (USB) WLAN, 802.11s Express) Mesh Ethernet RealTek 8139 None RealTek 8139 Atheros AR8132 JZ4730 10/01/00 10/100 10/100 10/100/1000 (Gigabit) USB Two Type-A USB 2.0 Three Type-A USB Three Type-A USB Three Type-A USB Three Type-A USB 2.0 2.0, up to 1Amp 2.0 2.0 power supplied (total) Graphics Silicon Motion, Inc. -

Rationale and Design for the Peace Box an Electronic Device for Your Home Or Office

Rationale and Design for the Peace Box An Electronic Device for your Home or Office A thesis submitted by Markus Sabadello, Austria, [email protected] to the European Peace University (EPU) – Private University Stadtschlaining/Burg, Austria in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Master of Arts Degree in Peace and Conflict Studies 1/23/2012 This thesis offers a summary of different lines of thought on how Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) can be used for promoting the ideal of peace, for example by helping to manage a crisis, by supporting development and education, by overcoming authoritaran regimes, or by promoting a global civil society and global culture of peace. After introducing these ideas, the concept of a „Peace Box“ is presented, which is a small computer-like device that can be set up in any home or office to provide applications and services for actively supporting the various visions of using ICTs for peace. Contents 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 1 1.1. ICTs for Peace .................................................................................................................................. 2 1.2. ICTs against Peace ......................................................................................................................... 4 2. Technological Considerations ........................................................................................................... -

Ενσωμάτωση Πλατφόρμας Croquet Στο Olpc-Xo

ΑΡΙΣΤΟΤΕΛΕΙΟ ΠΑΝΕΠΙΣΤΗΜΙΟ ΘΕΣΣΑΛΟΝΙΚΗΣ ΤΜΗΜΑ ΠΛΗΡΟΦΟΡΙΚΗΣ ΜΕΤΑΠΤΥΧΙΑΚΟ ΠΡΟΓΡΑΜΜΑ ΣΠΟΥΔΩΝ στην ΠΛΗΡΟΦΟΡΙΚΗ ΚΑΤΕΥΘΥΝΣΗ: ΤΕΧΝΟΛΟΓΙΕΣ ΠΛΗΡΟΦΟΡΙΑΣ & ΕΠΙΚΟΙΝΩΝΙΩΝ ΣΤΗΝ ΕΚΠΑΙΔΕΥΣΗ Ασημακόπουλος Αλέξανδρος «Ενσωμάτωση και εκτέλεση του τρισδιάστατου συνεργατικού εικονικού περιβάλλοντος Croquet σε εικονική αναπαράσταση του λειτουργικού συστήματος του φορητού υπολογιστή OLPC- XO» (Integration and execution of the 3-d collaborative virtual environment Croquet on an emulated image of the OLPC-XO laptop operating system) Επιβλέπων: ΘΡΑΣΥΒΟΥΛΟΣ Κ. ΤΣΙΑΤΣΟΣ Λέκτορας Διπλωματική Εργασία που υποβάλλεται στο πλαίσιο της μερικής εκπλήρωσης των απαιτήσεων για την απόκτηση Μεταπτυχιακού Διπλώματος στην Πληροφορική με εξειδίκευση στη Κατεύθυνση «Τεχνολογίες Πληροφορίας & Επικοινωνιών στην Εκπαίδευση» ΘΕΣΣΑΛΟΝΙΚΗ, 2008 Η ΤΡΙΜΕΛΗΣ ΕΞΕΤΑΣΤΙΚΗ ΕΠΙΤΡΟΠΗ ΝΙΚΟΛΑΟΣ ΒΑΣΙΛΕΙΑΔΗΣ, Επίκουρος Καθηγητής ΣΤΑΥΡΟΣ ΔΗΜΗΤΡΙΑΔΗΣ, Επίκουρος Καθηγητής ΘΡΑΣΥΒΟΥΛΟΣ Κ. ΤΣΙΑΤΣΟΣ, Λέκτορας Η έγκριση της Διπλωματικής αυτής Εργασίας από το Τμήμα Πληροφορικής του Αριστοτέλειου Πανεπιστήμιου Θεσσαλονίκης δεν υποδηλώνει την αποδοχή των γνωμών του συγγραφέα. (Νόμος 5343/32, άρθρο 202, παρ. 2) 2 ΠΕΡΙΛΗΨΗ Αντικείμενο της παρούσας εργασίας είναι η μελέτη ενσωμάτωσης του τρισδιάστατου συνεργατικού εικονικού περιβάλλοντος Croquet στο λειτουργικό σύστημα του Φθηνού Μαθητικού Φορητού Υπολογιστή (One Laptop Per Child OLPC-XO. Κατά την διάρκεια της εργασίας εξετάστηκε εάν η ανοιχτού κώδικα πλατφόρμα Croquet μπορεί να υποστηριχθεί από το λειτουργικό σύστημα του φορητού υπολογιστή OLPC-XO και σε ποιόν βαθμό αυτό θα μπορούσε να γίνει, με ποιες απαιτήσεις – κόστος σε πόρους όσον αφορά και τα 2 συστήματα. Η αρχική μελέτη δομήθηκε πάνω σε μια ακολουθία σταδίων, ο στόχος και τα αποτελέσματα των οποίων περιγράφονται παρακάτω: Στάδιο 0: Στόχος του σταδίου αυτού ήταν η μελέτη υπάρχουσας βιβλιογραφίας για το OLPC, σε τι στάδιο βρίσκονται οι ομάδες ανάπτυξης σε Ελλάδα και εξωτερικό, τι έχει αναπτυχθεί, τι αναπτύσσεται αυτή την στιγμή σε λογισμικό - υλικό, ποιες οι δυνατότητες του σήμερα. -

The One Laptop Per Child (OLPC) XO-1 Laptop and the Sugar Interface Problem

The One Laptop Per Child (OLPC) XO-1 Laptop and the Sugar Interface Problem How can technology assist education of children in the third world, to improve their economic situation? Analysis of technology ● More interactivity than traditional means ● New content can be acquired easily ● Wider variety of uses ● Increases students' familiarity with technology ● Simplified collaboration with other students, even over large distances ● Higher up-front cost ● Thus less students can use it ● Lesson plans must be changed Solution: OLPC XO ● Low up-front cost (200USD/child) ● Large volume of pre-existing educational content that has been adapted from other sources ● No software royalties, entirely Free Software ● Makes use of open content (textbooks, artwork) so that students can share information with each other without violating laws. Background Nicholas Negroponte co-founder of the MIT Media Lab in 1985 The Media Lab was founded on principles of constructionist learning Laptop projects previously tried in Senegal, Pakistan, Columbia and Cambodia Nicholas steps down from Media Lab in 2004 to form 503 c(3) non- profit, One Laptop Per Child OLPC founded on the bold notion that every child in the developing world should have their own laptop to use as they would a pencil SugarLabs separate from OLPC to focus on Sugar development Why OLPC and Sugar ICT can be a powerful tool for education child-centric educator driven teacher assisting Why OLPC and Sugar ICT can be a powerful tool for education child-centric educator driven teacher assisting