Microfilmed - 1064 Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

House Committee to Reagan: Invoke War Powers Act Associated Press Which Long Opposes Would Allow Said

---------------- ---~ Computers - page6 VOL XVIII, NO. 20 tht: indt:pt:ndt:nt studt:nt nt:w~papt:r ~t:n ing rwtn dame and ~aint mary·~ THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 22, 1983 House committee to Reagan: Invoke War Powers Act Associated Press which Long opposes would allow said. the Marines to remain another 18 At the same time, Shultz refused to WASHINGTON - The House Ap months, but would be initiated by say if Reagan would seek further propriations Committee voted yes Congress, not by the president as congressional approval if the terday to cut off funds for U.S. forces spelled out in the Vietnam-era War Marines are still in Lebanon after the in Lebanon unless President Reagan Power Act. 18 months spelled out in the com agrees to invoke the War Powers Act Reagan has also said he has con promise war powers resolution acknowledging a congressional role stitutional objections to the War worked out between Reagan and in deciding how long 1,200 U.S. Powers Act, even though he has congressional leaders. Marines should remain in Beirut. agreed to sign the compromise "I don't think the president will The 20-16 party line vote marks a worked out after careful negotia have to make a flat statement on repudiation of a compromise War tions with senior White House aides. what he's going to do about the Powers resolution agreed to by deployment of U.S. forces 18 months Reagan and most congressional In the Senate on Tuesday, from now," the secretary said. leaders, including Democratic Secretary of State George Shultz said . -

Ronald Reagan 1St Edition Kindle

RONALD REAGAN 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Michael Schaller | 9780199751747 | | | | | Ronald Reagan 1st edition PDF Book Their marriage ended in divorce in Signed by Ronald Reagan directly on title page. Signed by Author s. This Book has been Viewed Time s. Signed copy of a later printing of the first edition of the autobiography of the 40th U. The copy present here is fully authentic. Published by Random House She was good at sartorial messaging. I learned so much more about her! Such a weird and formal request; it's a men's suit that is most popular at daytime weddings. Cloth-backed boards. See Article History. Hamner called Wyman "one of the legendary stars In a glittering East Room ceremony on December 8th, the two leaders signed the historic INF Treaty, eliminating all nuclear-armed ground-launched ballistic and cruise missiles with ranges between and 5, kilometers. First edition so stated. Cloth-backed boards. Edited by Douglas Brinkley. Ready, Willing, and Able. A member of the Dominican Order as a lay tertiary of the Catholic Church, she was buried in a nun's habit. NO markings throughout - NO rem mark or ex-lib. Cue the eye roll. Bennett: Such a snapshot of her psychological state. Clean and crisp copy. Dust Jacket Condition: Very Good. Myron Futterman. Ron" The writing seems a bit shaky and hesitant, and therefore may be somewhat suspect. I once lived around the corner from the house Nancy grew up in. They married in and divorced in I also found it interesting that Nancy pulled her hair back when her short, feathered look was so recognizable. -

The President's Inauguration, P. 6 Review Chief

The president's inauguration, p. 6 Today's weather: A fi~ star Increasing clouds AU-Ameriron NON PROFIT ORG towards the evening, -yaper US POSTAGE 50 percent chance PAID of rain. High Newark Del in the mid 50s. Permtl No 26 Student Center, University of Delaware, Newark, Delaware 19716 Tuesday, October 27, 1987 Review chief resigns post Review Editor in Chief Mike Freeman resigned Sunday night following university notification that he could not be readmitted as a student this semester because he had not registered nor paid his tuition on time. According to Dean of Students Timothy Brooks, Freeman " was not a student" all semester. Freeman said he only received notification in early Mike Freeman September that his student registration was cancelled, but " The university knew I ow said the university insisted he ed the money and they could THE was notified over the summer. not let me go without paying," r1JiiiMAne tall- Newly inaugurated President Russel C. Jones addresses invited guests dur- The university informed said the English journalism celebration on the South Mall. Freeman last week that he major from Columbia, Md. Student organizations are . verst· ty memo down,"~~jt~:~~~~~~fJd~~~~~~~~~ Brooks said. "He required to register with the nl made the decision to step university annually, Brooks down." said, and must name six ex A staff member for almost ecutive officers who are full • time matriculated students. two years, Freeman said he 0 t d f t h a Z 1ng believed his problems could be Freeman said he will e r a resume classes at the univer rectified over the course of the sity during Winter Session. -

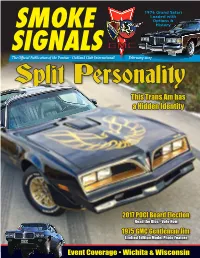

This Trans Am Has a Hidden Identity

1976 Grand Safari Loaded with Options & SMOKE History SIGNALS GR RRR The Official Publication of the Pontiac - Oakland Club International February 2017 Split Personality This Trans Am has a Hidden Identity 2017 POCI Board Election Read the Bios - Vote Now 1975 GMC Gentleman Jim Limited Edition Model Photo Feature Event Coverage • Wichita & Wisconsin First-Born Bandit This unique special edition Trans Am is the by Richard Price the early ‘70s, General Mo- tors Design Vice President Bill Mitchell was intrigued by the black-and-gold John Player Specials then racing in Formula 1. Being an avid motorcycle enthusiast, he had a pair of his personal bikes done up in this same color scheme and was pleased enough with it that he made a suggestion to Pontiac Design Stu- dio #2 Director John Schinella that he apply it to a Trans Am. Schinella requisitioned a Buccaneer Red 455 automatic ‘73 Trans Am which was deliv- ered to the Design Center paint shop, where the entire car — including the rear bumper — was painted a custom black metallic lacquer with gold metalflakes mixed in. The tailpipes, grilles and head- light bezels were painted metallic gold and the Hon- eycomb wheels were covered with a genuine gold coating. Gold pinstriping was then applied around the grille openings, wheel arches, rear bumper, the upper portion of the car, around all of the glass openings and over the roof. Finally, special one-off Trans Am decals (including the hood bird, made from a gold foil) were applied. 22 SMOKE SIGNALS • FEBRUARY 2017 has Split Personality earliest known production Y82 in existence photos - various contributors Inside, the otherwise stock Trans Am Deluxe inte- rior was redone in a light tan with a parachute-silk fabric on the horsecollar buckets. -

Burt Reynolds, Sally Field and Jackie Gleason Hit the Highway As 1977'S

* * MEDIA ALERT * * MEDIA ALERT * * MEDIA ALERT * * May 3, 2017 Burt Reynolds, Sally Field and Jackie Gleason Hit the Highway as 1977’s Blockbuster Action-Comedy Smokey and the Bandit Returns to U.S. Cinemas May 21 and 24 This Iconic Film Returns to Big Screens Nationwide for 40th Anniversary as Part of TCM Big Screen Classics Series WHAT: The summer of 1977 might be best known for a certain intergalactic adventure, but across the country the other summertime smash combined three things America couldn’t get enough of: Burt Reynolds, CB radio and Coors beer. Forty years later, Smokey and the Bandit makes its way back to movie screens nationwide for two days only on Sunday, May 21 and Wednesday, May 24 as part of the year-long TCM Big Screen Classics series from Turner Classic Movies and Fathom Events. This screening will also include specially- produced commentary from TCM host Ben Mankiewicz, both before and after the feature. “The Bandit” (Reynolds) has 28 hours to drive a truckload of Coors beer from Texarkana, Texas, to Atlanta – while doing everything he can to avoid the relentless pursuit of “Smokey,” aka Sheriff Buford T. Justice (Jackie Gleason), while accompanied by runaway bride “Frog” (Sally Field). But the story takes a backseat to the stunt-driven action of director Hal Needham, the still-sizzling on-screen chemistry of Reynolds and Field, and the good-ol’-boy antics of the film’s easy-going cast, including Jerry Reed, Paul Williams, Pat McCormick and Mike Henry. WHO: Fathom Events, Turner Classic Movies and Universal Pictures WHEN: Sunday, May 21, 2017; 2:00 p.m. -

It T S B U R G H G A

T n N u W a Pennsylvania’s n largest weekly ITTS BURGH G ATH circulation >4798\ Friday, September 30, 1983 139th Year, CXLIV No. 29 15 Cents - DUQUESNE UNIVERSITY olic Newspaper in Continuous Publication a I mR ARI AN __ L O C U S T Cathc P 1 T T S B Catholic Inside educators school in to gather Braddock to dose Oct. 13-14 By STEPHEN KARLINCHAK By STEPHEN KARL1NCHAK One of the oldest, continuously “ Catholic Schools: Rooted in operating Catholic schools ui the Faith, Fashioned by Hope and diocese, St. Thomas District High Expressed in Love,” is the theme School in Braddock. will close at for this year’s Tri-Diocesan the end of the 1982-83 academic J e s u its Catholic Teachers Institute. year. More than 3,500 teachers, The diocesan school board made Jesuits describe their first principals and administrators — the decision to close St. Thomas at ‘Arab’ superior general. Page 6. priests. Religious brothers and iu Sept 20 meeting Students were sisters, and lay persons — from informed of the closing at an the Pittsburgh, Greensburg and assem b ly on Sept. 21. An Altoona-Johnstown dioceses will information meeting for parents attend the two-day conference on to discuss their questions about Thursday and Friday, Oct. 13 and continuing Catholic education for 14, at the Monroeville Merchan their children was held on Sept 22 dise Mart/Expo Center. A decline in the potential In addition to the teachers and number of students and the hard- administrators from the three pressed economy affected the dioceses, 40 elementary and school's enrollment said Sister Movie review secondary school teachers and Josephine Macias. -

'77 Pontiac ® Firebird ®

KIT 4027 85402700200 NOTE: DO NOT DIP DECAL # 28, 29 IN WATER. CAREFULLY CUT OUT AND USE WHITE GLUE TO ATTACH. REMARQUE: NE PAS IMMERGER DANS L’EAU LES DÉCALCOMANIES # 28, 29. DÉCOUPER SOIGNEUSEMENT ET UTILISER DE LA COLLE BLANCHE POUR FIXER. ® ® 13 NOTA: NO SUMERJA LAS CALCOMANÍAS NO. 28, 29 EN AGUA. RECORTE CUIDADOSAMENTE Y UTILICE COLA BLANCA PARA SUJETAR. '77 PONTIAC FIREBIRD SMOKEY AND THE BANDIT ™ 35 32 30 1 4 Before there were cell phones, the CB radio was Avant l’avènement des téléphones cellulaires, la radio CB Antes de los teléfonos celulares, la radio de banda ciudadana 29 2 33 28 (CB, por sus siglas en inglés) era el medio de comunicación. THE form of communication. While not in the credits, était LE moyen de communication. Bien qu’elle ne figure pas au générique, la radio CB était la meilleure amie de Aunque no se incluyó en los créditos, la radio CB fue la the CB radio was the Bandit’s best friend in the hit mejor amiga del Bandido (Bandit) en la taquillera película 11 Bandit dans ce film à succès réalisé par Hal Needham. movie directed by Hal Needham. The Bandit, played Bandit, que personnifiait Burt Reynolds, utilisait sa radio dirigida por Hal Needham. El Bandido, interpretado por by Burt Reynolds, used his CB radio and gleaming CB et sa rutilante Firebird noire pour éviter de manière Burt Reynolds, utilizó su radio CB y su reluciente Firebird black Firebird to skillfully avoid Smokey, played for savante Smokey, que jouait pour nous faire rire Jackie negro para evitar hábilmente a Smokey, interpretado laughs by Jackie Gleason, on one long movie chase. -

The Impact of Media Violence on Children Hearing

S. HRG. 110–1181 THE IMPACT OF MEDIA VIOLENCE ON CHILDREN HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JUNE 26, 2007 Printed for the use of the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 76–392 PDF WASHINGTON : 2012 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 12:41 Nov 01, 2012 Jkt 075679 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 S:\GPO\DOCS\SCST0626 JACKIE SENATE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii, Chairman JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER IV, West Virginia TED STEVENS, Alaska, Vice Chairman JOHN F. KERRY, Massachusetts JOHN MCCAIN, Arizona BYRON L. DORGAN, North Dakota TRENT LOTT, Mississippi BARBARA BOXER, California KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas BILL NELSON, Florida OLYMPIA J. SNOWE, Maine MARIA CANTWELL, Washington GORDON H. SMITH, Oregon FRANK R. LAUTENBERG, New Jersey JOHN ENSIGN, Nevada MARK PRYOR, Arkansas JOHN E. SUNUNU, New Hampshire THOMAS R. CARPER, Delaware JIM DEMINT, South Carolina CLAIRE MCCASKILL, Missouri DAVID VITTER, Louisiana AMY KLOBUCHAR, Minnesota JOHN THUNE, South Dakota MARGARET L. CUMMISKY, Democratic Staff Director and Chief Counsel LILA HARPER HELMS, Democratic Deputy Staff Director and Policy Director CHRISTINE D. KURTH, Republican Staff Director and General Counsel KENNETH R. NAHIGIAN, Republican Deputy Staff Director and Chief Counsel (II) VerDate Nov 24 2008 12:41 Nov 01, 2012 Jkt 075679 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 S:\GPO\DOCS\SCST0626 JACKIE C O N T E N T S Page Hearing held on June 26, 2007 .............................................................................. -

DJ – Titres Incontournables

DJ – Titres incontournables Ce listing de titres constamment réactualisé , il vous ait destiné afin de surligner avec un code couleur ce que vous préférez afin de vous garantir une personnalisation totale de votre soirée . Si vous le souhaitez , il vaut mieux nous appeler pour vous envoyer sur votre mail la version la plus récente . Vous pouvez aussi rajouter des choses qui n’apparaissent pas et nous nous chargeons de trouver cela pour vous . Des que cette inventaire est achevé par vos soins , nous renvoyer par mail ce fichier adapté à vos souhaits 2018 bruno mars – finesse dj-snake-magenta-riddim-audio ed-sheeran-perfect-official-music-video liam-payne-rita-ora-for-you-fifty-shades-freed luis-fonsi-demi-lovato-echame-la-culpa ofenbach-vs-nick-waterhouse-katchi-official-video vitaa-un-peu-de-reve-en-duo-avec-claudio-capeo-clip-officiel 2017 amir-on-dirait april-ivy-be-ok arigato-massai-dont-let-go-feat-tessa-b- basic-tape-so-good-feat-danny-shah bastille-good-grief bastille-things-we-lost-in-the-fire bigflo-oli-demain-nouveau-son-alors-alors bormin-feat-chelsea-perkins-night-and-day burak-yeter-tuesday-ft-danelle-sandoval calum-scott-dancing-on-my-own-1-mic-1-take celine-dion-encore-un-soir charlie-puth-attention charlie-puth-we-dont-talk-anymore-feat-selena-gomez clean-bandit-rockabye-ft-sean-paul-anne-marie dj-khaled-im-the-one-ft-justin-bieber-quavo-chance-the-rapper-lil-wayne dj-snake-let-me-love-you-ft-justin-bieber enrique-iglesias-subeme-la-radio-remix-remixlyric-video-ft-cnco feder-feat-alex-aiono-lordly give-you-up-feat-klp-crayon -

00 Kwajalein Hourglass

.. 00 KWAJALEIN HOURGLASS VOLUME XXII, NO 67 U S ARMY KWAJALEIN MISSILE RANGE, MARSHALL ISLANDS FRIDAY, APRIL 5, 1985 Khartoum Reported In 'State Of Total ParalysIs' Large Explosion Rocks Baghdad SHULTZ, SECRET SERVICE By WADlE KIROLOS BAGHDAD, Iraq (UPI) -- A large exploslon rocked down INVESTIGATE DEATH THREATS town Baghdad today shortly af By HANZADA FIKRY cllned to comment on the Iden fesslonals called to protest ter Iran sald It flred a mlS CAIRO, Egypt (UPI) -- Com tltles of the callers recent hlkes In food and gas slle at the Iraql capItal In munlcatlon and alr llnks to Desplte the threats, a State prlces retallatlon for IraqI attacks the Sudanese capltal of Khar Department spokesman sald Nu Calro Alrport authorltles on Iranlan border towns that toum remalned severed today on melry met today wlth Secretary sald Khartoum A1rport remalned kliled at least 39 people the thlrd day of a general of State George Shultz for 45 closed for the second day today Iraq dId not conflrm the at strlke denounclng the govern mlnutes at the home of the Su and that telephone and 1nterna tack, and reporters who heard ment of Presldent Jaafar Nu danese ambassador The spokes tlonal telex llnes were cut for the bLast were barred from tra melry, who came under death man had no detalls of the talks a thlrd day velIng to the area In central threats In Washlngton Dlplomatlc sources In Calro, Mlnor demonstratlons were Baghdad where It occurred A Brltlsh Broadcastlng Corp meanwhlle, denled reports that reported Thursday, and the BBC Iran's offlclal -

Authorized Catalogs - United States

Authorized Catalogs - United States Miché-Whiting, Danielle Emma "C" Vic Music @Canvas Music +2DB 1 Of 4 Prod. 10 Free Trees Music 10 Free Trees Music (Admin. by Word Music Group, 1000 lbs of People Publishing 1000 Pushups, LLC Inc obo WB Music Corp) 10000 Fathers 10000 Fathers 10000 Fathers SESAC Designee 10000 MINUTES 1012 Rosedale Music 10KF Publishing 11! Music 12 Gate Recordings LLC 121 Music 121 Music 12Stone Worship 1600 Publishing 17th Avenue Music 19 Entertainment 19 Tunes 1978 Music 1978 Music 1DA Music 2 Acre Lot 2 Dada Music 2 Hour Songs 2 Letit Music 2 Right Feet 2035 Music 21 Cent Hymns 21 DAYS 21 Songs 216 Music 220 Digital Music 2218 Music 24 Fret 243 Music 247 Worship Music 24DLB Publishing 27:4 Worship Publishing 288 Music 29:11 Church Productions 29:Eleven Music 2GZ Publishing 2Klean Music 2nd Law Music 2nd Law Music 2PM Music 2Surrender 2Surrender 2Ten 3 Leaves 3 Little Bugs 360 Music Works 365 Worship Resources 3JCord Music 3RD WAVE MUSIC 4 Heartstrings Music 40 Psalms Music 442 Music 4468 Productions 45 Degrees Music 4552 Entertainment Street 48 Flex 4th Son Music 4th teepee on the right music 5 Acre Publishing 50 Miles 50 States Music 586Beats 59 Cadillac Music 603 Publishing 66 Ford Songs 68 Guns 68 Guns 6th Generation Music 716 Music Publishing 7189 Music Publishing 7Core Publishing 7FT Songs 814 Stops Today 814 Stops Today 814 Today Publishing 815 Stops Today 816 Stops Today 817 Stops Today 818 Stops Today 819 Stops Today 833 Songs 84Media 88 Key Flow Music 9t One Songs A & C Black (Publishers) Ltd A Beautiful Liturgy Music A Few Good Tunes A J Not Y Publishing A Little Good News Music A Little More Good News Music A Mighty Poythress A New Song For A New Day Music A New Test Catalog A Pirates Life For Me Music A Popular Muse A Sofa And A Chair Music A Thousand Hills Music, LLC A&A Production Studios A. -

The Rev. Donald E. Wildmon's Crusade for Censorship, 1977-1989

The Rev. Donald E. wildmon's Crusade for Censorship, 1977-1989 By Christopher M. Finan "What we are up against is not dirty words and 4irty pictures. It is a phi.losophy of life which seeks to remove the influence of Christians and Christianity from our society. Pornography is not the disease, but merely a visible symptom. It springs from a moral cancer in our society, and it will lead us to destruction if we are unable to stop it." ---The Rev. Donald E. Wildman The Rev. Donald E. Wildmon has always claimed to be an "average guy." When he first came to the attention of the public, he was the leader of a boycott against advertisers who sponsored "sex, violence and profanity" on television. Wildmon insisted that he was not a censor but an outraged private citizen who was exercising his constitutional right to protest. But, Wildmon is not an average citizen. His ambition is to remake American society. Nor is he content with the instruments of change provided by democratic institutions: he advocates the censorship of television, movies, books, and magazines. During his 12-year campaign for censorship, he has tried to suppress: * Television series like "charlie's Angels," "Three's Company," "All in the Family," "Laverne and Shirley," "Love, Sidney," "Taxi, II "WKRP in Cincinnati, II "Hill Street Blues," "Moonlighting," "L.A. Law," "thirtysomethinq;" * Television dramas like "Roe v. Wade," Pete Hamillis "Flesh and Blood," Maya Angelouls "Sister, Sister" and "Portrait of a Rebel: Margaret Sanger;1I * Movies like liThe Last Temptation of Christi" * Magazines like Playboy, Penthouse and Sassy.