Asgap Indigenous Orchid Study Group Issn 1036-9651

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Does Population Structure Analysis Reveal About the Pterostylis Longifolia Complex (Orchidaceae)? Jasmine K

What does population structure analysis reveal about the Pterostylis longifolia complex (Orchidaceae)? Jasmine K. Janes1,2, Dorothy A. Steane1 & Rene´ E. Vaillancourt1 1School of Plant Science, University of Tasmania, Private Bag 55, Hobart, Tasmania, 7001, Australia 2Biological Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, T6G 2E9, Canada Keywords Abstract AFLP, conservation, hybridization, refugia, speciation, taxonomy. Morphologically similar groups of species are common and pose significant challenges for taxonomists. Differences in approaches to classifying unique spe- Correspondence cies can result in some species being overlooked, whereas others are wrongly Jasmine K. Janes, School of Plant Science, conserved. The genetic diversity and population structure of the Pterostylis lon- University of Tasmania, Private Bag 55, gifolia complex (Orchidaceae) in Tasmania was investigated to determine if four Hobart, 7001 Tasmania, Australia. Tel: +1 species, and potential hybrids, could be distinguished through genomic AFLP 780 492 0587; Fax: +1 780 492 9234; E-mail: [email protected] and chloroplast restriction-fragment-length polymorphism (RFLP) markers. Analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) results indicated that little genetic Funding Information variation was present among taxa, whereas PCoA analyses revealed genetic This research was funded by a Discovery variation at a regional scale irrespective of taxa. Population genetic structure grant (DPO557260) from the Australian analyses identified three clusters that correspond to regional genetic and single Research Council, an Australian Postgraduate taxon-specific phenotypic variation. The results from this study suggest that Award to the lead author and research “longifolia” species have persisted throughout the last glacial maximum in Tas- funding from the Australian Systematic mania and that the complex may be best treated as a single taxon with several Botany Society (Hansjo¨ rg Eichler Scientific Research Fund). -

Ecology and Ex Situ Conservation of Vanilla Siamensis (Rolfe Ex Downie) in Thailand

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Chaipanich, Vinan Vince (2020) Ecology and Ex Situ Conservation of Vanilla siamensis (Rolfe ex Downie) in Thailand. Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) thesis, University of Kent,. DOI Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/85312/ Document Version UNSPECIFIED Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html Ecology and Ex Situ Conservation of Vanilla siamensis (Rolfe ex Downie) in Thailand By Vinan Vince Chaipanich November 2020 A thesis submitted to the University of Kent in the School of Anthropology and Conservation, Faculty of Social Sciences for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Abstract A loss of habitat and climate change raises concerns about change in biodiversity, in particular the sensitive species such as narrowly endemic species. Vanilla siamensis is one such endemic species. -

Locally Threatened Plants in Manningham

Locally Threatened Plants in Manningham Report by Dr Graeme S. Lorimer, Biosphere Pty Ltd, to Manningham City Council Version 1.0, 28 June, 2010 Executive Summary A list has been compiled containing 584 plant species that have been credibly recorded as indigenous in Manningham. 93% of these species have been assessed by international standard methods to determine whether they are threatened with extinction in Manningham. The remaining 7% of species are too difficult to assess within the scope of this project. It was found that nineteen species can be confidently presumed to be extinct in Manningham. Two hundred and forty-six species, or 42% of all indigenous species currently growing in Manningham, fall into the ‘Critically Endangered’ level of risk of extinction in the municipality. This is an indication that if current trends continue, scores of plant species could die out in Manningham over the next decade or so – far more than have become extinct since first settlement. Another 21% of species fall into the next level down on the threat scale (‘Endangered’) and 17% fall into the third (‘Vulnerable’) level. The total number of threatened species (i.e. in any of the aforementioned three levels) is 466, representing 82% of all indigenous species that are not already extinct in Manningham. These figures indicate that conservation of indigenous flora in Manningham is at a critical stage. This also has grave implications for indigenous fauna. Nevertheless, corrective measures are possible and it is still realistic to aim to maintain the existence of every indigenous plant species presently in the municipality. The scope of this study has not allowed much detail to be provided about corrective measures except in the case of protecting threatened species under the Manningham Planning Scheme. -

Sistemática Y Evolución De Encyclia Hook

·>- POSGRADO EN CIENCIAS ~ BIOLÓGICAS CICY ) Centro de Investigación Científica de Yucatán, A.C. Posgrado en Ciencias Biológicas SISTEMÁTICA Y EVOLUCIÓN DE ENCYCLIA HOOK. (ORCHIDACEAE: LAELIINAE), CON ÉNFASIS EN MEGAMÉXICO 111 Tesis que presenta CARLOS LUIS LEOPARDI VERDE En opción al título de DOCTOR EN CIENCIAS (Ciencias Biológicas: Opción Recursos Naturales) Mérida, Yucatán, México Abril 2014 ( 1 CENTRO DE INVESTIGACIÓN CIENTÍFICA DE YUCATÁN, A.C. POSGRADO EN CIENCIAS BIOLÓGICAS OSCJRA )0 f CENCIAS RECONOCIMIENTO S( JIOI ÚGIC A'- CICY Por medio de la presente, hago constar que el trabajo de tesis titulado "Sistemática y evo lución de Encyclia Hook. (Orchidaceae, Laeliinae), con énfasis en Megaméxico 111" fue realizado en los laboratorios de la Unidad de Recursos Naturales del Centro de Investiga ción Científica de Yucatán , A.C. bajo la dirección de los Drs. Germán Carnevali y Gustavo A. Romero, dentro de la opción Recursos Naturales, perteneciente al Programa de Pos grado en Ciencias Biológicas de este Centro. Atentamente, Coordinador de Docencia Centro de Investigación Científica de Yucatán, A.C. Mérida, Yucatán, México; a 26 de marzo de 2014 DECLARACIÓN DE PROPIEDAD Declaro que la información contenida en la sección de Materiales y Métodos Experimentales, los Resultados y Discusión de este documento, proviene de las actividades de experimen tación realizadas durante el período que se me asignó para desarrollar mi trabajo de tesis, en las Unidades y Laboratorios del Centro de Investigación Científica de Yucatán, A.C., y que a razón de lo anterior y en contraprestación de los servicios educativos o de apoyo que me fueron brindados, dicha información, en términos de la Ley Federal del Derecho de Autor y la Ley de la Propiedad Industrial, le pertenece patrimonialmente a dicho Centro de Investigación. -

Biodiversity Summary: Port Phillip and Westernport, Victoria

Biodiversity Summary for NRM Regions Species List What is the summary for and where does it come from? This list has been produced by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPC) for the Natural Resource Management Spatial Information System. The list was produced using the AustralianAustralian Natural Natural Heritage Heritage Assessment Assessment Tool Tool (ANHAT), which analyses data from a range of plant and animal surveys and collections from across Australia to automatically generate a report for each NRM region. Data sources (Appendix 2) include national and state herbaria, museums, state governments, CSIRO, Birds Australia and a range of surveys conducted by or for DEWHA. For each family of plant and animal covered by ANHAT (Appendix 1), this document gives the number of species in the country and how many of them are found in the region. It also identifies species listed as Vulnerable, Critically Endangered, Endangered or Conservation Dependent under the EPBC Act. A biodiversity summary for this region is also available. For more information please see: www.environment.gov.au/heritage/anhat/index.html Limitations • ANHAT currently contains information on the distribution of over 30,000 Australian taxa. This includes all mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs and fish, 137 families of vascular plants (over 15,000 species) and a range of invertebrate groups. Groups notnot yet yet covered covered in inANHAT ANHAT are notnot included included in in the the list. list. • The data used come from authoritative sources, but they are not perfect. All species names have been confirmed as valid species names, but it is not possible to confirm all species locations. -

Australian Orchidaceae: Genera and Species (12/1/2004)

AUSTRALIAN ORCHID NAME INDEX (21/1/2008) by Mark A. Clements Centre for Plant Biodiversity Research/Australian National Herbarium GPO Box 1600 Canberra ACT 2601 Australia Corresponding author: [email protected] INTRODUCTION The Australian Orchid Name Index (AONI) provides the currently accepted scientific names, together with their synonyms, of all Australian orchids including those in external territories. The appropriate scientific name for each orchid taxon is based on data published in the scientific or historical literature, and/or from study of the relevant type specimens or illustrations and study of taxa as herbarium specimens, in the field or in the living state. Structure of the index: Genera and species are listed alphabetically. Accepted names for taxa are in bold, followed by the author(s), place and date of publication, details of the type(s), including where it is held and assessment of its status. The institution(s) where type specimen(s) are housed are recorded using the international codes for Herbaria (Appendix 1) as listed in Holmgren et al’s Index Herbariorum (1981) continuously updated, see [http://sciweb.nybg.org/science2/IndexHerbariorum.asp]. Citation of authors follows Brummit & Powell (1992) Authors of Plant Names; for book abbreviations, the standard is Taxonomic Literature, 2nd edn. (Stafleu & Cowan 1976-88; supplements, 1992-2000); and periodicals are abbreviated according to B-P- H/S (Bridson, 1992) [http://www.ipni.org/index.html]. Synonyms are provided with relevant information on place of publication and details of the type(s). They are indented and listed in chronological order under the accepted taxon name. Synonyms are also cross-referenced under genus. -

May 2019 – the Greenhood

May2019 ... 1. 1. Volume 61 … no. 5 Pterostylis alata* (striped greenhood) now flowering in Hobart region. Green and brown striped solitary flower on tall scape. leaves only present on sterile (non flowering) GREENHOOD plants. Grows in open forest in damper areas They say it is worth listening to a “MASTER” and an Photo by Geoff Curry “Apprentice” talking about their similar passions. Contents Well at our next meeting Monday 20th May @ 7.30 pm at Special Interest articles. Legacy House is when “Master” Noel Doyle will discuss the pros and cons of potting “fernmania” and President’ Report p 3. “apprentice” Peter Manchester will show why it is Sunday get together p 5. important to water potting bark efficiently. Cultural notes p 6. This will happen while judging of the Autumn Show is April meeting results p. 7/8 occurring in the “supper” room under the guidance of May Autumn Show p 9. Show Marshall Jim Smith. Facebook orchid groups p 11. May is our Autumn Show… will you “bench” by Orchid roots ?? p13. 7.15 pm? Growing seed orchids p 14. See pages 9… For the show schedule .. be in it. Watering&Misting p17. Copy Deadline is the 5th May 2019 OFFICE BEARERS for TAS. ORCHID SOCIETY MAJOR other EVENTS 2019/20 THROUGHOUT THE YEAR… PRESIDENT Peter Willson …62484375 TOS Autumn Show 20th May 2019. Senior Vice President TOS Spring Show 26th Sept. to Sept. 29th 2019 Vicki Cleaver … 62450140 Vice President Glenn Durkin …62492226 SECRETARY/Public GREENHOOD editor Peter S Manchester 0477432640 … Officer [email protected] Bev Woodward WEB MANAGER Michael Jaschenko … http://tos.org.au/ 0413136413 [email protected] TREASURER Christine Doyle… 62729820 [email protected] May 20th - presentations by Noel Doyle & Peter Manchester. -

11. Species Names & Their Synonyms

11. Species Names & Their Synonyms This is an alphabetical listing of South Australia’s native orchids as they appear in this disk. Names in brown are the names used in this book. The names indented under these are equivalent names that have been used in other publications. The names in bold are those used by the State Herbarium of South Australia. Undescribed species that are not included in the Census of South Australian plants are in red. This census can be checked online at: www.flora.sa.gov.au/census.shtml. The last printed version was published on 18 March 2005. This list is a comprehensive list of the alternative names or synonyms that have been or are being used for each of the species dealt with in this book. It enables the species names used in this book to be related to names used in other publications. The Find function in Adobe Reader will allow a reader to look up any name used in another publication and determine the name or names used herein. Acianthus pusillus D.L.Jones - Acianthus exsertus auct.non R.Br.: J.Z.Weber & R.J.Bates(1986) Anzybas fordhamii (Rupp) D.L.Jones - Corybas fordhamii (Rupp)Rupp - Corysanthes fordhamii Rupp Anzybas unguiculatus (R.Br.) D.L.Jones & M.A.Clem. - Corybas unguiculatus (R.Br.)Rchb.f. - Corysanthes unguiculata R.Br. Arachnorchis argocalla (D.L.Jones) D.L.Jones & M.A.Clem. - Caladenia argocalla D.L.Jones - Caladenia patersonii auct.non R.Br.: J.Z.Weber & R.J.Bates(1986), partly - Calonema argocallum (D.L.Jones)Szlach. -

Download a PDF Sample of the ANOS Vic. Bulletin

AUSTRALASIAN NATIVE ORCHID TIVE O NA RC N H SOCIETY (VICTORIAN GROUP) INC. IA ID Reg. No. A0007188C ABN No. 678 744 287 84 S S A O L C A I E R T T Y S BULLETIN U A NOVEMBER 2019 V I . Volume 52 Issue 5 C C T N Print Post Approved PP.34906900044 Price: $1.00 OR P I IAN GROU Visit our web site at: http://www.anosvic.org.au NEXT MEETING FRIDAY 1ST NOVEMBER AT 8.OOPM Venue open at 7.00pm for set-up, benching and inspecting plants, Sales Table, Library and socialising. For insurance purposes, please sign our attendance book as you enter the hall. GLEN WAVERLEY COMMUNITY CENTRE 700 WAVERLEY ROAD, GLEN WAVERLEY Melway Map 71 / C4/5 (Opposite Allen Street) Entry / Parking: Central Reserve - Community Centre / Bowling Club, west from Springvale Road. ITEM OF THE EVENING WESTERN AUSTRALIA’S SUPERB SUN ORCHIDS by ANDREW BROWN The Australasian Native Orchid Society promotes the conservation Dendrobium gracilicaule of native orchids through cultivation and through preservation of their natural habitat. photographed by John Varigos. All native orchids are protected plants in the wild; their collection is illegal. Always seek permission before entering private property. ANOS VICTORIAN GROUP BULLETIN - PAGE 2 DIRECTORY UNLESS OTHERWISE SPECIFIED, THE POSTAL ADDRESS OF EVERYONE IN THIS DIRECTORY IS: ANOS VIC, PO BOX 308, BORONIA VIC 3155 President - George Byrne-Dimos Secretary - Susan Whitten Mob: 0438-517-813. Committee 1. Jonathon Harrison 9802-4925 [email protected] [email protected] Mob: 0490-450-974 [email protected] Vice President 1 - John Varigos Treasurer - Stan Harper Committee 2. -

AUSTRALIAN ORCHID NAME INDEX (27/4/2006) by Mark A. Clements

AUSTRALIAN ORCHID NAME INDEX (27/4/2006) by Mark A. Clements and David L. Jones Centre for Plant Biodiversity Research/Australian National Herbarium GPO Box 1600 Canberra ACT 2601 Australia Corresponding author: [email protected] INTRODUCTION The Australian Orchid Name Index (AONI) provides the currently accepted scientific names, together with their synonyms, of all Australian orchids including those in external territories. The appropriate scientific name for each orchid taxon is based on data published in the scientific or historical literature, and/or from study of the relevant type specimens or illustrations and study of taxa as herbarium specimens, in the field or in the living state. Structure of the index: Genera and species are listed alphabetically. Accepted names for taxa are in bold, followed by the author(s), place and date of publication, details of the type(s), including where it is held and assessment of its status. The institution(s) where type specimen(s) are housed are recorded using the international codes for Herbaria (Appendix 1) as listed in Holmgren et al’s Index Herbariorum (1981) continuously updated, see [http://sciweb.nybg.org/science2/IndexHerbariorum.asp]. Citation of authors follows Brummit & Powell (1992) Authors of Plant Names; for book abbreviations, the standard is Taxonomic Literature, 2nd edn. (Stafleu & Cowan 1976-88; supplements, 1992-2000); and periodicals are abbreviated according to B-P-H/S (Bridson, 1992) [http://www.ipni.org/index.html]. Synonyms are provided with relevant information on place of publication and details of the type(s). They are indented and listed in chronological order under the accepted taxon name. -

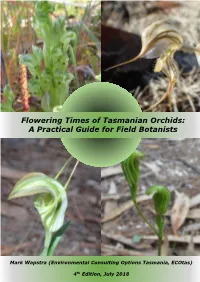

Flowering Times of Tasmanian Orchids: a Practical Guide for Field Botanists

Flowering Times of Tasmanian Orchids: A Practical Guide for Field Botanists Mark Wapstra (Environmental Consulting Options Tasmania, ECOtas) 4th Edition, July 2018 Flowering Times of Tasmanian Orchids: A Practical Guide for Field Botanists 4th Edition (July 2018) MARK WAPSTRA Flowering Times of Tasmanian Orchids: A Practical Guide for Field Botanists FOREWORD TO FIRST EDITION (2008) This document fills a significant gap in the Tasmanian orchid literature. Given the inherent difficulties in locating and surveying orchids in their natural habitat, an accurate guide to their flowering times will be an invaluable tool to field botanists, consultants and orchid enthusiasts alike. Flowering Times of Tasmanian Orchids: A Practical Guide for Field Botanists has been developed by Tasmania’s leading orchid experts, drawing collectively on many decades of field experience. The result is the most comprehensive State reference on orchid flowering available. By virtue of its ease of use, accessibility and identification of accurate windows for locating our often-cryptic orchids, it will actually assist in conservation by enabling land managers and consultants to more easily comply with the survey requirements of a range of land-use planning processes. The use of this guide will enhance efforts to locate new populations and increase our understanding of the distribution of orchid species. The Threatened Species Section commends this guide and strongly recommends its use as a reference whenever surveys for orchids are undertaken. Matthew Larcombe Project Officer (Threatened Orchid and Euphrasia) Threatened Species Section, Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water & Environment March 2008 DOCUMENT AVAILABILITY This document is freely available as a PDF file downloadable from the following websites: www.fpa.tas.gov.au; www.dpipwe.tas.gov.au; www.ecotas.com.au. -

Journal Native Orchid Society of South Australia Inc

JOURNAL of the NATIVE ORCHID SOCIETY OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA INC. PRINT POST APPROVED VOLUME 21 NO. 6 PP 543662 / 00018 JULY 1997 NATIVE ORCHID SOCIETY OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA INC. PO Box 565, UNLEY SA 5061 The Native Orchid Society of South Australia promotes the conservation of native orchids through cultivation of native orchids, through preservation of naturally-occurring orchid plants and natural habitat. Except with the documented official representation from the Management Committee of the native orchid society of South Australia, no person is authorised to represent the society on any matter. All native orchids are protected plants in the wild. Their collection without written Government permit is illegal. PATRON: Mr T.R.N. Lothian PRESIDENT: SECRETARY: Mr George Nieuwenhoven Cathy Houston Telephone: 8264 5825 Telephone: 8356 7356 VICE-PRESIDENT: TREASURER: Mr Roy Hargreaves Mr Ron Robjohns COMMITTEE: LIFE MEMBERS: Mr J. Peace Mr R. Hargreaves Mr D. Hirst Mr R. T. Robjohns Mrs T. Bridle Mr L. Nesbitt Mr D. Pettifor Mr D. Wells Mr G Carne Mr J Simmons (deceased) Mr H Goldsack (deceased) EDITOR: Bob Bates REGISTRAR OF JUDGES: 38 Portmarnock Street Fairview Park 5126 Mr L. Nesbitt Telephone: 8251 2443 JOURNAL COST: $1 PER ISSUE The Native Orchid Society of South Australia Inc. while taking all care, take no responsibility for the loss, destruction or damage to any plants whether at benchings, shows, exhibits or on the sales table or for any losses attributed to the use of any material published in this Journal or of action taken on advice or views expressed by any member or invited speaker at any meeting or exhibition.