Mohawk River Watershed Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fulmer Creek Basin Assessment

EMERGENCY TRANSPORTATION INFRASTRUCTURE RECOVERY WATER BASIN ASSESSMENT AND FLOOD HAZARD MITIGATION ALTERNATIVES FULMER CREEK HERKIMER COUNTY, NEW YORK April 2014 MMI #5231-01 Photo Source: Milone and MacBroom, Inc. (2013) This document was prepared for the New York State Department of Transportation, In cooperation with the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Prepared by: MILONE & MACBROOM, INC. 134 Main Street, Suite A1 New Paltz, NY 12561 (845) 633-8153 www.miloneandmacbroom.com Copyright 2014 Milone & MacBroom, Inc. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Project Background ...................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Nomenclature ............................................................................................................... 3 2.0 DATA COLLECTION .......................................................................................................... 3 2.1 Initial Data Collection .................................................................................................. 3 2.2 Public Outreach ............................................................................................................ 3 2.3 Field Assessment .......................................................................................................... 3 2.4 Watershed Land Use ................................................................................................... -

Mohawk River Watershed – HUC-12

ID Number Name of Mohawk Watershed 1 Switz Kill 2 Flat Creek 3 Headwaters West Creek 4 Kayaderosseras Creek 5 Little Schoharie Creek 6 Headwaters Mohawk River 7 Headwaters Cayadutta Creek 8 Lansing Kill 9 North Creek 10 Little West Kill 11 Irish Creek 12 Auries Creek 13 Panther Creek 14 Hinckley Reservoir 15 Nowadaga Creek 16 Wheelers Creek 17 Middle Canajoharie Creek 18 Honnedaga 19 Roberts Creek 20 Headwaters Otsquago Creek 21 Mill Creek 22 Lewis Creek 23 Upper East Canada Creek 24 Shakers Creek 25 King Creek 26 Crane Creek 27 South Chuctanunda Creek 28 Middle Sprite Creek 29 Crum Creek 30 Upper Canajoharie Creek 31 Manor Kill 32 Vly Brook 33 West Kill 34 Headwaters Batavia Kill 35 Headwaters Flat Creek 36 Sterling Creek 37 Lower Ninemile Creek 38 Moyer Creek 39 Sixmile Creek 40 Cincinnati Creek 41 Reall Creek 42 Fourmile Brook 43 Poentic Kill 44 Wilsey Creek 45 Lower East Canada Creek 46 Middle Ninemile Creek 47 Gooseberry Creek 48 Mother Creek 49 Mud Creek 50 North Chuctanunda Creek 51 Wharton Hollow Creek 52 Wells Creek 53 Sandsea Kill 54 Middle East Canada Creek 55 Beaver Brook 56 Ferguson Creek 57 West Creek 58 Fort Plain 59 Ox Kill 60 Huntersfield Creek 61 Platter Kill 62 Headwaters Oriskany Creek 63 West Kill 64 Headwaters South Branch West Canada Creek 65 Fly Creek 66 Headwaters Alplaus Kill 67 Punch Kill 68 Schenevus Creek 69 Deans Creek 70 Evas Kill 71 Cripplebush Creek 72 Zimmerman Creek 73 Big Brook 74 North Creek 75 Upper Ninemile Creek 76 Yatesville Creek 77 Concklin Brook 78 Peck Lake-Caroga Creek 79 Metcalf Brook 80 Indian -

Rartioter Vol

rartioter Vol. XII, No. 1 WINTER 1 9 7 9 BLACK DOME IN 1924 The Catskill Mountains have been known to white men for three hundred years and their valleys have been settled more than a cen- tury. It would seem as if all their summits ought by this time to be easily accessible by well known trails. Yet there are a dozen or more of the higher ones, above 3500 feet, which have no trails to their summits and which are climbed only by the exploring hiker, or perhaps a bear hunter in winter. I recently found another trackless peak, Black Dome, just under 4000 feet--3990 according to the Durham sheet of the United States Geological Survey--on a week-end climb in the northern Catskills. There is no trail over it, and the only paths that reach its flanks are faded out logging roads in the valleys north and south, attain- ing heights 1500 feet below its highest point. Black Dome is the central and highest of the three peaks that make up the Blackhead Mountains, running east and west, Black Head being the easternmost, then Black Dome and the last Thomas Cole. The other two are about fifty feet lower than the Dome. South of them is the valley of the East Kill, north that of Batavia Kill. North of Black Head runs a long ridge to Acra Point, then turning west to Windham High Peak. South this ridge runs through North Mountain and Stoppel Mountain to Kaaterskill Clove. Black Head is accessible by a good trail. -

New York City Department of Environmental Protection Bureau of Water Supply Filtration Avoidance 6.1 Project Activities For

New York City Department of Environmental Protection Bureau of Water Supply Filtration Avoidance 6.1 Project Activities For the period April 1, 2020 through September 30, 2020 October 2020 Prepared in accordance with Section 6.1 of the NYSDOH Revised 2017 Filtration Avoidance Determination Prepared by: DEP, Bureau of Water Supply Table of Contents, Part 6.1.1 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 2. DEP Organization and Responsibilities .............................................................................. 1 3. Specific Watershed Activities .............................................................................................. 2 3.1. SEQRA Projects Summary..................................................................................... 2 3.1.1. West of Hudson .................................................................................... 2 3.1.2. East of Hudson ....................................................................................... 6 3.2. Projects Under Construction .................................................................................. 8 3.2.1. West of Hudson .................................................................................... 8 3.2.2. East of Hudson .................................................................................... 13 3.3. New Projects ...................................................................................................... 15 3.3.1. West of -

Wetland Jurisdictional Determination Report

Case 10-T-0139 Hearing Exhibit 17 Page 1 of 38 WETLAND DELINEATION REPORT Champlain Hudson Power Express Project Albany, Saratoga, Schenectady, New York, Washington, and Westchester Counties, New York Prepared for: Champlain Hudson Power Express, Inc. Toronto, Ontario Prepared by: TRC ENVIRONMENTAL CORPORATION Wannalancit Mills 650 Suffolk St Lowell, MA 01854 March 2010 Case 10-T-0139 Hearing Exhibit 17 Page 2 of 38 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION..............................................................................................................1 2.0 PROJECT OVERVIEW ...................................................................................................1 3.0 WETLAND DELINEATION METHODOLOGY .........................................................2 4.0 WETLAND DELINEATION RESULTS ........................................................................4 4.1 Vegetation..............................................................................................................17 4.2 Hydrology ..............................................................................................................19 4.3 Soils........................................................................................................................20 4.4 Natural Resource Conservation Service Soil Series Descriptions.........................20 5.0 REFERENCES.................................................................................................................32 TABLES Table 4-1 Summary of Wetlands Within the Study Area ........................................................5 -

Erie Canalway Map & Guide

National Park Service Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor U.S. Department of the Interior Erie Canalway Map & Guide Pittsford, Frank Forte Pittsford, The New York State Canal System—which includes the Erie, Champlain, Cayuga-Seneca, and Oswego Canals—is the centerpiece of the Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor. Experience the enduring legacy of this National Historic Landmark by boat, bike, car, or on foot. Discover New York’s Dubbed the “Mother of Cities” the canal fueled the growth of industries, opened the nation to settlement, and made New York the Empire State. (Clinton Square, Syracuse, 1905, courtesy Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Detroit Publishing Extraordinary Canals Company Collection.) pened in 1825, New York’s canals are a waterway link from the Atlantic Ocean to the Great Lakes through the heart of upstate New York. Through wars and peacetime, prosperity and This guide presents exciting Orecession, flood and drought, this exceptional waterway has provided a living connection things to do, places to go, to a proud past and a vibrant future. Built with leadership, ingenuity, determination, and hard work, and exceptional activities to the canals continue to remind us of the qualities that make our state and nation great. They offer us enjoy. Welcome! inspiration to weather storms and time-tested knowledge that we will prevail. Come to New York’s canals this year. Touch the building stones CONTENTS laid by immigrants and farmers 200 years ago. See century-old locks, lift Canals and COVID-19 bridges, and movable dams constructed during the canal’s 20th century Enjoy Boats and Boating Please refer to current guidelines and enlargement and still in use today. -

The East Kill Management Plan

The East Kill Management Plan April 2007 PREPARED BY THE GREENE COUNTY SOIL AND WATER CONSERVATION DISTRICT NEW YORK CITY DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION East Kill Management Plan April 2007 Developed By Greene County Soil & Water Conservation District 907 County Office Building, Cairo NY 12514 Phone (518) 622-3620 Fax (518) 622-0344 www.gcswcd.com/stream/schoharie-eastkill Project Team Abbe Martin, East Kill SMP Project Manager Amy DeGaetano, Conservation Planner Carrie Miles, AmeriCorps Member Rene’ VanSchaack, Executive Director NYCDEP Stream Management Program 71 Smith Ave, Kingston NY 124021 Phone (845) 340-7519 Fax (845) 340-7514 Project Team David Burns, Project Manager Elizabeth Reichheld, Stream Program Manager East Kill Management Plan Table of Contents i. Table of Contents ii. Preface and Acknowledgements 1. Introduction 1.1 Purpose of the East Kill Management Plan 1.2 East Kill and its Watershed 1.3 How are we all connected to the East Kill and Why should I care? 1.4 What are the primary concerns in the East Kill Watershed? 1.5 Past, Current, and Future Activities 1.6 Goals and Objectives for this Management Plan 2. East Kill Natural and Institutional Resources 2.1 Regional Setting 2.2 Watershed History 2.3 Physical Geography (including Climate Change) 2.4 Hydrology and Flood History 2.5 Geology 2.6 Wetlands & Floodplains 2.7 Riparian Vegetation 2.8 Landuse/Landcover 2.9 Fisheries & Wildlife (Wildlife Biodiversity) 2.10 Recreational Opportunities 2.11 Stakeholders 2.12 Agency Contacts and Program Resources 2.13 Stream-related Activities and Permit Requirements 3. Watershed Inventory & Assessment 3.1 Water Quality Assessment 3.2 Introduction to Stream Processes 3.3 Watershed Inventory & Assessment 4. -

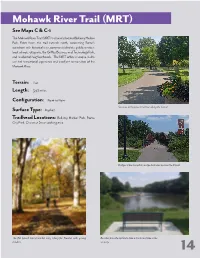

Mohawk River Trail (MRT) See Maps C & C-1 the Mohawk River Trail (MRT) Trailhead Is Located Bellamy Harbor Park

Mohawk River Trail (MRT) See Maps C & C-1 The Mohawk River Trail (MRT) trailhead is located Bellamy Harbor Park. From there, the trail extends north, connecting Rome’s waterfront with historical sites, commercial districts, public services, local schools, city parks, the Griffiss Business and Technology Park, and residential neighborhoods. The MRT offers a unique multi- use trail recreational experience and excellent scenic vistas of the Mohawk River. Terrain: Flat Length: 3.97 miles Configuration: Point to Point Sections of the paved trail run along the Canal. Surface Type: Asphalt Trailhead Locations: Bellamy Harbor Park, Rome City Park, Chestnut Street parking area. Bridges allow bicyclists and pedestrians to cross the Canal. The flat paved trail provides easy riding for families with young Benches provide a place to take a break and take in the children. scenery. 14 ! S s S i p r d P u r d L r o R a e i l R n p e e M ll d H R H r T C g h vi te n u n a u e i r n s e C d e b n n l e l R e so l C t r a st d r e R l P n k R e e R g r d e in e g o p W L ki y r o R d Lee l R r n a e ck i d l d b d o R a i R d M t n W S l T n l S i ! t G R Center Stokes Weste Westernville iffo South rnville H rd d Rd ! ! H e T Slon Lee C Rd ill R Hill Rd h enter d o Stoke C m s Brookfield Rd Rd t a H S m a a l D C l F s i n o w i r l a S h o ki r t a o vi R n n d ki d u d d ield R er s M yd okf d s T R Town of e so n Bro R n n d Delta vans n E R e Delta Lake R r ! Western d Rd E d Terrace R State Park d D o !5 R H Lee !5 p M i a 46 d l p rsh Town Park l Lee -

NENHC 2008 Abstracts

Abstracts APRIL 17 – APRIL 18, 2008 A FORUM FOR CURRENT RESEARCH The Northeastern Naturalist The New York State Museum is a program of The University of the State of New York/The State Education Department APRIL 17 – APRIL 18, 2008 A FORUM FOR CURRENT RESEARCH SUGGESTED FORMAT FOR CITING ABSTRACTS: Abstracts Northeast Natural History Conference X. N.Y. State Mus. Circ. 71: page number(s). 2008. ISBN: 1-55557-246-4 The University of the State of New York THE STATE EDUCATION DEPARTMENT ALBANY, NY 12230 THE UNIVERSITY OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK Regents of The University ROBERT M. BENNETT, Chancellor, B.A., M.S. ................................................................. Tonawanda MERRYL H. TISCH, Vice Chancellor, B.A., M.A., Ed.D. ................................................. New York SAUL B. COHEN, B.A., M.A., Ph.D.................................................................................. New Rochelle JAMES C. DAWSON, A.A., B.A., M.S., Ph.D. .................................................................. Peru ANTHONY S. BOTTAR, B.A., J.D. ..................................................................................... Syracuse GERALDINE D. CHAPEY, B.A., M.A., Ed.D. ................................................................... Belle Harbor ARNOLD B. GARDNER, B.A., LL.B. .................................................................................. Buffalo HARRY PHILLIPS, 3rd, B.A., M.S.F.S. ............................................................................. Hartsdale JOSEPH E. BOWMAN, JR., B.A., -

Wetlands of Saratoga County New York

Acknowledgments THIS BOOKLET I S THE PRODUCT Of THE work of many individuals. Although it is based on the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's National Wetlands Inventory (NWI), tlus booklet would not have been produced without the support and cooperation of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Patrick Pergola served as project coordinator for the wetlands inventory and Dan Montella was project coordinator for the preparation of this booklet. Ralph Tiner coordi nated the effort for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS). Data compiled from the NWI serve as the foun dation for much of this report. Information on the wetland status for this area is the result of hard work by photointerpreters, mainly Irene Huber (University of Massachusetts) with assistance from D avid Foulis and Todd Nuerminger. Glenn Smith (FWS) provided quality control of the interpreted aerial photographs and draft maps and collected field data on wetland communities. Tim Post (N.Y. State D epartment of Environmental Conservation), John Swords (FWS), James Schaberl and Chris Martin (National Park Ser vice) assisted in the field and the review of draft maps. Among other FWS staff contributing to this effort were Kurt Snider, Greg Pipkin, Kevin Bon, Becky Stanley, and Matt Starr. The booklet was reviewed by several people including Kathleen Drake (EPA), G eorge H odgson (Saratoga County Environmental Management Council), John Hamilton (Soil and W ater Conserva tion District), Dan Spada (Adirondack Park Agency), Pat Riexinger (N.Y. State Department of Environ mental Conservation), Susan Essig (FWS), and Jen nifer Brady-Connor (Association of State Wetland Nlanagers). -

Mohawk River Canoe Trip August 5, 2015

Mohawk River Canoe Trip August 5, 2015 A short field guide by Kurt Hollocher The trip This is a short, 2-hour trip on the Mohawk River near Rexford Bridge. We will leave from the boat docks, just upstream (west) of the south end of the bridge. We will probably travel in a clockwise path, first paddling west toward Scotia, then across to the mouth of the Alplaus Kill. Then we’ll head east to see an abandoned lock for a branch of the Erie Canal, go under the Rexford Bridge and by remnants of the Erie Canal viaduct, to the Rexford cliffs. Then we cross again to the south bank, and paddle west back to the docks. Except during the two river crossings it is important to stay out of the navigation channel, marked with red and green buoys, and to watch out for boats. Depending on the winds, we may do the trip backwards. The river The Mohawk River drains an extensive area in east and central New York. Throughout most of its reach, it flows in a single, well-defined channel between uplands on either side. Here in the Rexford area, the same is true now, but it was not always so. Toward the end of the last Ice Age, about 25,000 years ago, ice covered most of New York State. As the ice retreated, a large valley glacier remained in the Hudson River Valley, connected to the main ice sheet a bit farther to the north, when most of western and central New York was clear of ice. -

Green Infrastructure Plan for Saratoga County Adopted November 21, 2006

Green Infrastructure Plan for Saratoga County Adopted November 21, 2006 Prepared by: Behan Planning Associates, LLC with Dodson Associates, Ltd. & American Farmland Trust Green Infrastructure Plan for Saratoga County Adopted November 21, 2006 Saratoga County Board of Supervisors Philip Barrett, Town of Clifton Park Raymond F. Callanan, Town of Ballston J. Gregory Connors, Town of Stillwater Anita Daly, Town of Clifton Park Kenneth De Cerce, Town of Halfmoon Alan Grattidge, Town of Charlton Harry Gutheil, Town of Moreau - Board Chairman George J. Hargrave, Town of Galway Richard C. Hunter, Sr., Town of Providence Albert Janik, Town of Greenfi eld Arthur J. Johnson, Town of Wilton Mary Ann Johnson, Town of Day Cheryl Keyrouze, City of Saratoga Springs John E. Lawler, Town of Waterford Richard B. Lucia, Town of Corinth Willard H. Peck, Town of Northumberland Jean Raymond, Town of Edinburg Thomas Richardson, City of Mechanicville Paul Sausville, Town of Malta Frank Thompson, Town of Milton Jeffrey Trottier Town of Hadley Thomas N. Wood III, Town of Saratoga Joanne Yepsen, City of Saratoga Springs Green Infrastructure Plan for Saratoga County Saratoga County Farmland and Open Space Preservation Committee Supervisor Bill Peck, Chairman Supervisor Arthur Johnson Supervisor Paul Sausville Supervisor Phillip C. Barrett Tom L. Lewis, Chairman, Saratoga County Planning Board David Miller, Executive Director, Audubon New York Lynn Schumann, Northeast Director, Land Trust Alliance Ex-Offi cio Members: David Wickerham, County Administrator Jaime O’Neill,