Wetlands of Saratoga County New York

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mohawk River Watershed – HUC-12

ID Number Name of Mohawk Watershed 1 Switz Kill 2 Flat Creek 3 Headwaters West Creek 4 Kayaderosseras Creek 5 Little Schoharie Creek 6 Headwaters Mohawk River 7 Headwaters Cayadutta Creek 8 Lansing Kill 9 North Creek 10 Little West Kill 11 Irish Creek 12 Auries Creek 13 Panther Creek 14 Hinckley Reservoir 15 Nowadaga Creek 16 Wheelers Creek 17 Middle Canajoharie Creek 18 Honnedaga 19 Roberts Creek 20 Headwaters Otsquago Creek 21 Mill Creek 22 Lewis Creek 23 Upper East Canada Creek 24 Shakers Creek 25 King Creek 26 Crane Creek 27 South Chuctanunda Creek 28 Middle Sprite Creek 29 Crum Creek 30 Upper Canajoharie Creek 31 Manor Kill 32 Vly Brook 33 West Kill 34 Headwaters Batavia Kill 35 Headwaters Flat Creek 36 Sterling Creek 37 Lower Ninemile Creek 38 Moyer Creek 39 Sixmile Creek 40 Cincinnati Creek 41 Reall Creek 42 Fourmile Brook 43 Poentic Kill 44 Wilsey Creek 45 Lower East Canada Creek 46 Middle Ninemile Creek 47 Gooseberry Creek 48 Mother Creek 49 Mud Creek 50 North Chuctanunda Creek 51 Wharton Hollow Creek 52 Wells Creek 53 Sandsea Kill 54 Middle East Canada Creek 55 Beaver Brook 56 Ferguson Creek 57 West Creek 58 Fort Plain 59 Ox Kill 60 Huntersfield Creek 61 Platter Kill 62 Headwaters Oriskany Creek 63 West Kill 64 Headwaters South Branch West Canada Creek 65 Fly Creek 66 Headwaters Alplaus Kill 67 Punch Kill 68 Schenevus Creek 69 Deans Creek 70 Evas Kill 71 Cripplebush Creek 72 Zimmerman Creek 73 Big Brook 74 North Creek 75 Upper Ninemile Creek 76 Yatesville Creek 77 Concklin Brook 78 Peck Lake-Caroga Creek 79 Metcalf Brook 80 Indian -

S T a T E O F N E W Y O R K 3695--A 2009-2010

S T A T E O F N E W Y O R K ________________________________________________________________________ 3695--A 2009-2010 Regular Sessions I N A S S E M B L Y January 28, 2009 ___________ Introduced by M. of A. ENGLEBRIGHT -- Multi-Sponsored by -- M. of A. KOON, McENENY -- read once and referred to the Committee on Tourism, Arts and Sports Development -- recommitted to the Committee on Tour- ism, Arts and Sports Development in accordance with Assembly Rule 3, sec. 2 -- committee discharged, bill amended, ordered reprinted as amended and recommitted to said committee AN ACT to amend the parks, recreation and historic preservation law, in relation to the protection and management of the state park system THE PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK, REPRESENTED IN SENATE AND ASSEM- BLY, DO ENACT AS FOLLOWS: 1 Section 1. Legislative findings and purpose. The legislature finds the 2 New York state parks, and natural and cultural lands under state manage- 3 ment which began with the Niagara Reservation in 1885 embrace unique, 4 superlative and significant resources. They constitute a major source of 5 pride, inspiration and enjoyment of the people of the state, and have 6 gained international recognition and acclaim. 7 Establishment of the State Council of Parks by the legislature in 1924 8 was an act that created the first unified state parks system in the 9 country. By this act and other means the legislature and the people of 10 the state have repeatedly expressed their desire that the natural and 11 cultural state park resources of the state be accorded the highest 12 degree of protection. -

Wetland Jurisdictional Determination Report

Case 10-T-0139 Hearing Exhibit 17 Page 1 of 38 WETLAND DELINEATION REPORT Champlain Hudson Power Express Project Albany, Saratoga, Schenectady, New York, Washington, and Westchester Counties, New York Prepared for: Champlain Hudson Power Express, Inc. Toronto, Ontario Prepared by: TRC ENVIRONMENTAL CORPORATION Wannalancit Mills 650 Suffolk St Lowell, MA 01854 March 2010 Case 10-T-0139 Hearing Exhibit 17 Page 2 of 38 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION..............................................................................................................1 2.0 PROJECT OVERVIEW ...................................................................................................1 3.0 WETLAND DELINEATION METHODOLOGY .........................................................2 4.0 WETLAND DELINEATION RESULTS ........................................................................4 4.1 Vegetation..............................................................................................................17 4.2 Hydrology ..............................................................................................................19 4.3 Soils........................................................................................................................20 4.4 Natural Resource Conservation Service Soil Series Descriptions.........................20 5.0 REFERENCES.................................................................................................................32 TABLES Table 4-1 Summary of Wetlands Within the Study Area ........................................................5 -

Erie Canalway Map & Guide

National Park Service Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor U.S. Department of the Interior Erie Canalway Map & Guide Pittsford, Frank Forte Pittsford, The New York State Canal System—which includes the Erie, Champlain, Cayuga-Seneca, and Oswego Canals—is the centerpiece of the Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor. Experience the enduring legacy of this National Historic Landmark by boat, bike, car, or on foot. Discover New York’s Dubbed the “Mother of Cities” the canal fueled the growth of industries, opened the nation to settlement, and made New York the Empire State. (Clinton Square, Syracuse, 1905, courtesy Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Detroit Publishing Extraordinary Canals Company Collection.) pened in 1825, New York’s canals are a waterway link from the Atlantic Ocean to the Great Lakes through the heart of upstate New York. Through wars and peacetime, prosperity and This guide presents exciting Orecession, flood and drought, this exceptional waterway has provided a living connection things to do, places to go, to a proud past and a vibrant future. Built with leadership, ingenuity, determination, and hard work, and exceptional activities to the canals continue to remind us of the qualities that make our state and nation great. They offer us enjoy. Welcome! inspiration to weather storms and time-tested knowledge that we will prevail. Come to New York’s canals this year. Touch the building stones CONTENTS laid by immigrants and farmers 200 years ago. See century-old locks, lift Canals and COVID-19 bridges, and movable dams constructed during the canal’s 20th century Enjoy Boats and Boating Please refer to current guidelines and enlargement and still in use today. -

Contribution of Plant-Induced Pressurized Flow to CH4 Emission

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Contribution of plant‑induced pressurized fow to CH4 emission from a Phragmites fen Merit van den Berg2*, Eva van den Elzen2, Joachim Ingwersen1, Sarian Kosten 2, Leon P. M. Lamers 2 & Thilo Streck1 The widespread wetland species Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin. ex Steud. has the ability to transport gases through its stems via a pressurized fow. This results in a high oxygen (O2) transport to the rhizosphere, suppressing methane (CH4) production and stimulating CH4 oxidation. Simultaneously CH4 is transported in the opposite direction to the atmosphere, bypassing the oxic surface layer. This raises the question how this plant-mediated gas transport in Phragmites afects the net CH4 emission. A feld experiment was set-up in a Phragmites‑dominated fen in Germany, to determine the contribution of all three gas transport pathways (plant-mediated, difusive and ebullition) during the growth stage of Phragmites from intact vegetation (control), from clipped stems (CR) to exclude the pressurized fow, and from clipped and sealed stems (CSR) to exclude any plant-transport. Clipping resulted in a 60% reduced difusive + plant-mediated fux (control: 517, CR: 217, CSR: −2 −1 279 mg CH4 m day ). Simultaneously, ebullition strongly increased by a factor of 7–13 (control: −2 −1 10, CR: 71, CSR: 126 mg CH4 m day ). This increase of ebullition did, however, not compensate for the exclusion of pressurized fow. Total CH4 emission from the control was 2.3 and 1.3 times higher than from CR and CSR respectively, demonstrating the signifcant role of pressurized gas transport in Phragmites‑stands. -

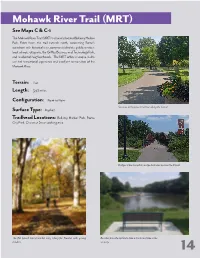

Mohawk River Trail (MRT) See Maps C & C-1 the Mohawk River Trail (MRT) Trailhead Is Located Bellamy Harbor Park

Mohawk River Trail (MRT) See Maps C & C-1 The Mohawk River Trail (MRT) trailhead is located Bellamy Harbor Park. From there, the trail extends north, connecting Rome’s waterfront with historical sites, commercial districts, public services, local schools, city parks, the Griffiss Business and Technology Park, and residential neighborhoods. The MRT offers a unique multi- use trail recreational experience and excellent scenic vistas of the Mohawk River. Terrain: Flat Length: 3.97 miles Configuration: Point to Point Sections of the paved trail run along the Canal. Surface Type: Asphalt Trailhead Locations: Bellamy Harbor Park, Rome City Park, Chestnut Street parking area. Bridges allow bicyclists and pedestrians to cross the Canal. The flat paved trail provides easy riding for families with young Benches provide a place to take a break and take in the children. scenery. 14 ! S s S i p r d P u r d L r o R a e i l R n p e e M ll d H R H r T C g h vi te n u n a u e i r n s e C d e b n n l e l R e so l C t r a st d r e R l P n k R e e R g r d e in e g o p W L ki y r o R d Lee l R r n a e ck i d l d b d o R a i R d M t n W S l T n l S i ! t G R Center Stokes Weste Westernville iffo South rnville H rd d Rd ! ! H e T Slon Lee C Rd ill R Hill Rd h enter d o Stoke C m s Brookfield Rd Rd t a H S m a a l D C l F s i n o w i r l a S h o ki r t a o vi R n n d ki d u d d ield R er s M yd okf d s T R Town of e so n Bro R n n d Delta vans n E R e Delta Lake R r ! Western d Rd E d Terrace R State Park d D o !5 R H Lee !5 p M i a 46 d l p rsh Town Park l Lee -

GLOSSARY a Anoxic a Lack of Oxygen

ECOLOGY OF OLD WOMAN CREEK ESTUARY AND WATERSHED 13. GLOSSARY A anoxic A lack of oxygen. abiotic Non living or derived from non-living anthropogenic Developed by human beings; man- processes; factor contributing to an environment made. that is of a non-living nature. aqueous Of, or pertaining to water. ablation All processes by which snow and ice are aquifer A body of rock that is sufficiently permeable lost from a glacier, floating ice, or snow cover, to conduct groundwater and to yield economically including melting, evaporation (sublimation), significant quantities of water to springs and wells. wind erosion, and calving. artifact Anything made by man or showing signs of AD Used as a prefix or suffix to a date, denoting the human use; generally applied to tools, implements, number of years after the beginning of the Christian and other objects of human manufacture. calendar (Anno Domini). adventitious roots Roots growing laterally from the atlatl A Mexican term for a spear throwing device; a stem rather than from the main root. stick with a hook at one end that fits into a depression in the base of a spear and is used to aerenchyma Tissue with large, air-filled cavities lengthen the thrower’s arm, thus adding leverage between the cells that are present in the stems and and speed. roots of certain aquatic plants that enables adequate gaseous exchange below water. atlatl weights Stone objects fastened to the throwing stick for added mass. aerial Growing or borne above the ground or water; autochthonous Material generated within a particular of, for, or by means of aircraft (e.g. -

Mohawk River Canoe Trip August 5, 2015

Mohawk River Canoe Trip August 5, 2015 A short field guide by Kurt Hollocher The trip This is a short, 2-hour trip on the Mohawk River near Rexford Bridge. We will leave from the boat docks, just upstream (west) of the south end of the bridge. We will probably travel in a clockwise path, first paddling west toward Scotia, then across to the mouth of the Alplaus Kill. Then we’ll head east to see an abandoned lock for a branch of the Erie Canal, go under the Rexford Bridge and by remnants of the Erie Canal viaduct, to the Rexford cliffs. Then we cross again to the south bank, and paddle west back to the docks. Except during the two river crossings it is important to stay out of the navigation channel, marked with red and green buoys, and to watch out for boats. Depending on the winds, we may do the trip backwards. The river The Mohawk River drains an extensive area in east and central New York. Throughout most of its reach, it flows in a single, well-defined channel between uplands on either side. Here in the Rexford area, the same is true now, but it was not always so. Toward the end of the last Ice Age, about 25,000 years ago, ice covered most of New York State. As the ice retreated, a large valley glacier remained in the Hudson River Valley, connected to the main ice sheet a bit farther to the north, when most of western and central New York was clear of ice. -

Green Infrastructure Plan for Saratoga County Adopted November 21, 2006

Green Infrastructure Plan for Saratoga County Adopted November 21, 2006 Prepared by: Behan Planning Associates, LLC with Dodson Associates, Ltd. & American Farmland Trust Green Infrastructure Plan for Saratoga County Adopted November 21, 2006 Saratoga County Board of Supervisors Philip Barrett, Town of Clifton Park Raymond F. Callanan, Town of Ballston J. Gregory Connors, Town of Stillwater Anita Daly, Town of Clifton Park Kenneth De Cerce, Town of Halfmoon Alan Grattidge, Town of Charlton Harry Gutheil, Town of Moreau - Board Chairman George J. Hargrave, Town of Galway Richard C. Hunter, Sr., Town of Providence Albert Janik, Town of Greenfi eld Arthur J. Johnson, Town of Wilton Mary Ann Johnson, Town of Day Cheryl Keyrouze, City of Saratoga Springs John E. Lawler, Town of Waterford Richard B. Lucia, Town of Corinth Willard H. Peck, Town of Northumberland Jean Raymond, Town of Edinburg Thomas Richardson, City of Mechanicville Paul Sausville, Town of Malta Frank Thompson, Town of Milton Jeffrey Trottier Town of Hadley Thomas N. Wood III, Town of Saratoga Joanne Yepsen, City of Saratoga Springs Green Infrastructure Plan for Saratoga County Saratoga County Farmland and Open Space Preservation Committee Supervisor Bill Peck, Chairman Supervisor Arthur Johnson Supervisor Paul Sausville Supervisor Phillip C. Barrett Tom L. Lewis, Chairman, Saratoga County Planning Board David Miller, Executive Director, Audubon New York Lynn Schumann, Northeast Director, Land Trust Alliance Ex-Offi cio Members: David Wickerham, County Administrator Jaime O’Neill, -

Freshwater Fishing: a Driver for Ecotourism

New York FRESHWATER April 2019 FISHINGDigest Fishing: A Sport For Everyone NY Fishing 101 page 10 A Female's Guide to Fishing page 30 A summary of 2019–2020 regulations and useful information for New York anglers www.dec.ny.gov Message from the Governor Freshwater Fishing: A Driver for Ecotourism New York State is committed to increasing and supporting a wide array of ecotourism initiatives, including freshwater fishing. Our approach is simple—we are strengthening our commitment to protect New York State’s vast natural resources while seeking compelling ways for people to enjoy the great outdoors in a socially and environmentally responsible manner. The result is sustainable economic activity based on a sincere appreciation of our state’s natural resources and the values they provide. We invite New Yorkers and visitors alike to enjoy our high-quality water resources. New York is blessed with fisheries resources across the state. Every day, we manage and protect these fisheries with an eye to the future. To date, New York has made substantial investments in our fishing access sites to ensure that boaters and anglers have safe and well-maintained parking areas, access points, and boat launch sites. In addition, we are currently investing an additional $3.2 million in waterway access in 2019, including: • New or renovated boat launch sites on Cayuga, Oneida, and Otisco lakes • Upgrades to existing launch sites on Cranberry Lake, Delaware River, Lake Placid, Lake Champlain, Lake Ontario, Chautauqua Lake and Fourth Lake. New York continues to improve and modernize our fish hatcheries. As Governor, I have committed $17 million to hatchery improvements. -

Shore Lines the Saratoga Lake Association P.O

Shore Lines The Saratoga Lake Association P.O. Box 2152 Ballston Spa, NY 12020 www.saratogalake.org www.facebook.com/saratogalake/ November 3, 2014 Julie Annotto, co-editor Sharon Urban, co-editor [email protected] [email protected] What is taking so long to fill that bird feeder? Falling Into Winter A Message from the President Annual Holiday Party Panza's Restaurant I visited the Waterfront Park in the City of Saratoga Thursday, December 11, 2014 Springs which is closed for construction and am happy Carol Dooley – [email protected] to report that significant construction is occurring. Cathy McKenna—[email protected] Our Holiday Party will be at Panza's on Wednesday, Dianne Fedoronko—[email protected] December 11th. Ed Kinowski, Town of Stillwater Supervisor, will discuss plans for a Winterfest at Brown's Beach. Cash Bar for Entire Event We are still seeking a Chair of the Events Commit- 5:30-6:30PM tee. This is a very important role within SLA. Please let Chef’s Selection of Butler Served Hors D’oeuvres me know if you are interested or know of qualified candi- 6:30PM dates. Holiday Buffet Served Chopped Salad continued page 2 Warm Dinner Rolls and Creamery Butter Rigatoni a’La Jillian Another Membership Season Begins Soon (penne with broccoli, sundried tomatoes, reggiano, EVO) Chicken Franchaise Dear Members, Seafood Fra Diablo Please watch for your membership letters and forms Chef Carved Roast Beef Fingerling Potato in your mailbox during November. Seasonal Vegetables We are a fairly large organization and while making Holiday Dessert sure we comply with our legal and fiduciary responsibili- Brewed Regular and Decaffeinated Coffee and Herbal Teas ties it may appear some things have changed. -

Upper Hudson Woodlands ATP Conservation Easement

Upper Hudson Woodlands ATP Conservation Easement RECREATION MANAGEMENT PLAN Sacandaga Block Jackson Summit Road West Tract Dennie Road Tract Benson Road Tract Hohler Road Tract Johnny Cake Lake Tract Gordons Creek Road Tract Lake Desolation Road Tract NYS DEC, REGION 5, DIVISION OF LANDS AND FORESTS 701 North Main Street, Northville, NY 12134 [email protected] www.dec.ny.gov February 2017 Contents PREFACE 7 Use of Conservation Easements in New York State ............................................... 7 I. INTRODUCTION 8 Purpose of the Recreation Management Plan ........................................................ 8 II. PROPERTY OVERVIEW 9 A. Geographic Information .................................................................................... 9 1. P roperty Description and Access ....................................................................... 9 2. Tract Descriptions ............................................................................................ 10 III. NATURAL AND CULTURAL RESOURCES 11 A. Physical Resources ........................................................................................ 11 B. Biological Resources ...................................................................................... 13 C. Cultural Resources ......................................................................................... 16 D. Economic Impact ............................................................................................ 16 IV. RELATI ONSHIP OF PROPERTY TO ADJACENT LANDS 16 A. Public Property