The Bay of Pigs: the Botched Invasion of Cuba

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Consejo De Redacción De Convivencia: Obra De Portada: Director: Dagoberto Valdés Hernández “¡A La Mesa!” 2014 Karina Gálvez Chiú Mixta (Acrílico) Lienzo

Consejo de Redacción de Convivencia: Obra de Portada: Director: Dagoberto Valdés Hernández “¡A la mesa!” 2014 Karina Gálvez Chiú Mixta (Acrílico) Lienzo. 75 x 109 cm Maikel Iglesias Rodríguez Serie: “Dichoso el hombre que soporta la prueba...” Rosalia Viñas Lazo Santiago 1.12. No. 37 Livia Gálvez Chiú Obra: Alan Manuel González Henry Constantín Ferreiro Yoandy Izquierdo Toledo Contraportada: Serie “Postales del Hoyo del Guamá” (7) Diseño y Administración Web: Javier Valdés Delgado Foto: Maikel Iglesias Rodríguez Equipo de realización: Colaboradores permanentes: Composición computarizada: Yoani Sánchez Rosalia Viñas Lazo Reinaldo Escobar Casas Correcciones: Olga Lidia López Lazo Livia Gálvez Chiú Virgilio Toledo López Yoandy Izquierdo Toledo Asistencia Técnica: Contáctenos en: Arian Domínguez Bernal www.convivenciacuba.es Secretaría de Redacción: www.convivenciacuba.es/intramuros Hortensia Cires Díaz [email protected] Luis Cáceres Piñero Web master: [email protected] Marianela Gómez Luege Relaciones Públicas y Mensajería: Margarita Gálvez Martínez Juan Carlos Fernández Hernández Suscripciones por e-mail: Javier Valdés Delgado ([email protected]) Diseño digital para correo electrónico (HTML): Maikel Iglesias Rodríguez EN ESTE NÚMERO EDITORIAL Restablecer las relaciones democráticas entre el pueblo y el gobierno cubanos..................................5 CULTURA: ARTE, LITERATURA... Galería Curriculum vitae de Alan Manuel González...........................................................................................8 -

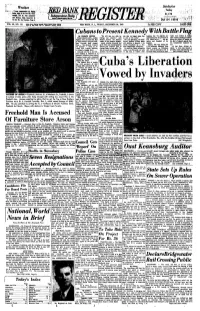

Cuba's Liberation Vowed by Invaders

Weather , 3 mm imftfttmt n. May, fety fat the tow Ms^. CJeaV BED BAM 21,175 (••Iffe few 2J. Fair (omorrew and foaday. High tomorrow la the law Mi. Sec Wealber, Pafe 2. Dial SH I-0010 VOL.' 85. NO 133 rria«7. amst CUM 1*14 «t « 4 Bt n RED BANK, N. J., FRIDAY, DECEMBER 28, 1962 7c PER COPY AUllil VUll O1UCM. Cubans toPresent Kennedy With Battle Flag By FRANCIS LEWINE "We will pay our debt by say that he hoped some day brigade, but "to express our rades were locked in Cuban PALM BEACH (AP) -Cuban freeing 'our country," said to visit a free Cuba." appreciation for his personal ef- ceils "naked, sleeping on floon, fighters who survived the Bay Manuel Artime, the political ' His eyes sparkling, the dark- fort which led to ... the sal- being the object of insults on of Pigs Invasion will give Presi-' leader of the invasion brigade. haired, youthful Artime spoke vation and freedom of the the part of Jptoial guards that dent Kennedy their combat Asked whether Kennedy had with emotion in Spanish — bis brigade. the Communists imposed on flag — "the greatest treasure given them any encouragement words translated by a U.S. Artime, who was among the us." . •• :•••.•: .-..'.• we possess" — when he re- toward this eventual goal of State Department interpreter. 1,113 prisoners liberated from "At that time, Artime re- views their brigade Saturday freeing Cuba, Artime said, "We He said the Cuban delegation Castro prisons on Christmas called, "a voice was heard, a in Miami's Orange Bowl. -

The Foreign Policies of Revolutionary Leaders: Identity

THE FOREIGN POLICIES OF REVOLUTIONARY LEADERS: IDENTITY, EMOTION, AND CONFLICT INITIATION by PATRICK MARTIN VAN ORDEN A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Political Science and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2018 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Patrick Martin Van Orden Title: The Foreign Policies of Revolutionary Leaders: Identity, Emotion, and Conflict Initiation This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of Political Science by: Tuong Vu Chairperson Jane Cramer Core Member Lars Skalnes Core Member Angela Joya Institutional Representative and Janet Woodruff-Borden Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded September 2018 ii © 2018 Patrick Martin Van Orden This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution (United States) License iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Patrick Martin Van Orden Doctor of Philosophy Department of Political Science September 2018 Title: The Foreign Policies of Revolutionary Leaders: Identity, Emotion, and Conflict Initiation This manuscript addresses an important empirical regularity: Why are revolutionary leaders more likely to initiate conflict? With the goal of explaining this regularity, I offer an identity-driven model of decision making that can explain why certain leaders are more likely to take risky gambles. Broadly, this manuscript provides a different model of decision making that emphasizes emotion and identity as key to explain decision making. I offer a plausibility probe of the identity-driven model with four in-depth case studies: The initiation of the Iran-Iraq War, the initiation of the Gulf War, the Cuban Missile Crisis, and the start of the Korean War. -

The Quest for Women's Liberation in Post Revolutionary Cuba

Eastern Washington University EWU Digital Commons EWU Masters Thesis Collection Student Research and Creative Works 2014 “A REVOLUTION WITHIN A REVOLUTION:” THE QUEST FOR WOMEN’S LIBERATION IN POST REVOLUTIONARY CUBA Mayra Villalobos Eastern Washington University Follow this and additional works at: http://dc.ewu.edu/theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Villalobos, Mayra, "“A REVOLUTION WITHIN A REVOLUTION:” THE QUEST FOR WOMEN’S LIBERATION IN POST REVOLUTIONARY CUBA" (2014). EWU Masters Thesis Collection. 224. http://dc.ewu.edu/theses/224 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research and Creative Works at EWU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in EWU Masters Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of EWU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “A REVOLUTION WITHIN A REVOLUTION:” THE QUEST FOR WOMEN’S LIBERATION IN POST REVOLUTIONARY CUBA A Thesis Presented To Eastern Washington University Cheney, Washington In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in History By Mayra Villalobos Spring 2014 ii THESIS OF MAYRA VILLALOBOS APPROVED BY DATE NAME OF CHAIR, GRADUATE STUDY COMMITTEE DATE NAME OF MEMBER, GRADUATE STUDY COMMITTEE iii MASTER’S THESIS In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Eastern Washington University, I agree that the JFK Library shall make copies freely available for inspection. I further agree that copying of this project in whole or in part is allowable only for scholarly purposes. It is understood, however, that any copying or publication of this thesis for commercial purposes, or for financial gain, shall not be allowed without my written permission. -

Redalyc.Blas Roca Y Las Luchas Obreras En Manzanillo (1925 – 1933)

Revista Izquierdas E-ISSN: 0718-5049 [email protected] Universidad de Santiago de Chile Chile Sera Fernández, Aida Mercedes; Reyes Arevich, Amada Blas Roca y las luchas obreras en Manzanillo (1925 – 1933) Revista Izquierdas, núm. 28, julio, 2016, pp. 137-161 Universidad de Santiago de Chile Santiago de Chile, Chile Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=360146329006 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Aida Sera - Amada Reyes, Blas Roca y las luchas obreras en Manzanillo (1925 – 1933), Izquierdas 28: 137-161, Julio 2016 Blas Roca y las luchas obreras en Manzanillo (1925 – 1933) Blas Roca and the fighting of worker at Manzanillo (1925 – 1933) 137 Aida Mercedes Sera Fernández* Amada Reyes Arevich** Resumen Al examinar el desenvolvimiento político de Blas Roca, uno de los momentos de mayor significación fue su vinculación a las trascendentales jornadas de la Revolución del 30. Este estudio ofrece los hitos más importantes de su actividad revolucionaria en Manzanillo, durante la etapa de 1925 a 1933, que lo iniciaron y definieron como dirigente del movimiento obrero y comunista ante el status político que frustró la independencia y la soberanía nacionales. Palabras clave: Blas Roca, Revolución del 30, Manzanillo, movimiento obrero y comunista cubano Abstract Examining Blas Roca’s political opening, one of the higher significance moments went his relationships in the momentous strikes of the thirtieth revolution. -

The Final Frontier: Cuban Documents on the Cuban Missile Crisis

SECTION 2: Latin America The Final Frontier: Cuban Documents on the Cuban Missile Crisis or most researchers probing the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Nikita Khrushchev) emissary Anastas Mikoyan near the end Cuban archives have been the final frontier—known to of his three-week November 1962 stay in Cuba; a summary exist, undoubtedly critical, yet largely and tantalizingly of Mikoyan’s subsequent conversation in Washington with US Fout of reach. For a little more than two decades, even as impor- President John F. Kennedy, conveyed to the Cubans at the UN tant archives remained shut (except to a few favored scholars), in New York by Moscow’s ambassador to the United States, Havana has occasionally and selectively released closed materials Anatoly F. Dobrynin; an internal report by communist party on the crisis, often in the context of international conferences. leader Blas Roca Calderio on his travels in Europe at the time This process began with Cuban participation in a series of “criti- of the crisis; and—perhaps most valuably for those seeking to cal oral history” conferences in 1989-92 with U.S. and Soviet understand Soviet-Cuban interactions after the crisis—a record (and then Russian) veterans of the events, which climaxed in a of the conversation in Moscow in December 1962 between January 1992 gathering in Havana at which Fidel Castro not Nikita Khrushchev and a visiting Carlos Rafael Rodriguez, only participated actively during all four days of discussions but evidently the first face-to-face meeting between the Soviet leader several times, with a figurative snap of the fingers, “declassified” and a senior Cuban communist figure since the Soviet leader’s important Cuban records.1 decision to withdraw the missiles, a step taken without advance Ten years later, in October 2002, to mark the 40th anniver- notice to or consultation with Havana that aroused consterna- sary of the crisis, Fidel Castro and the Cuban government again tion among the Cuban leadership and populace. -

November 21, 1960 Memorandum of Conversation Between Vice

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified November 21, 1960 Memorandum of Conversation between Vice-Chairman Zhou Enlai, Party Secretary of the Cuban Popular Socialist Party Manuel Luzardo, and Member of National Directory Ernesto Che Guevara Citation: “Memorandum of Conversation between Vice-Chairman Zhou Enlai, Party Secretary of the Cuban Popular Socialist Party Manuel Luzardo, and Member of National Directory Ernesto Che Guevara,” November 21, 1960, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, PRC FMA 204-00098-03, 1- 19. Translated for by Zhang Qian. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/115154 Summary: A diplomatic conversation covering China-Cuba relations, especially economic situations and the aid China is giving to Cuba. Credits: This document was made possible with support from the Leon Levy Foundation. Original Language: Chinese Contents: English Translation Memorandum of Conversation between Vice-Chairman Zhou Enlai, Party Secretary of the Cuban Popular Socialist Party Manuel Luzardo, and Member of National Directory Ernesto Che Guevara (without review of Vice-Chairman Zhou Enlai) Top Secret Venue: Xihua Hall of Zhongnanhai Time: 11:20-2:45 hours Accompanied by: Li Xiannian, Wu Xiuquan Interpreter: Cai Tongkuo Recorder: Zhang Zai Luzardo: Good health to the Premier. Zhou: Thanks (introduced comrade Wu Xiuquan). Luzardo: He joined our Congress of Representatives. Zhou: Thank you for your treatment of him. Luzardo: We were glad to treat him, only afraid of having not treated well. Zhou: You were so busy. Luzardo: It was our first time treating so many comrades from fraternal parties. Although we did want to treat them well, there many things that [we] didn’t do well. -

De La Biblioteca Nacional José Martí

AÑO 98, No. 3-4, JULIO-DICIEMBRE 2007 ISSN 0006-1727 RNPS 0383 • DE LA BIBLIOTECA-EVIS NACIONAL JOSÉ MARTÍ Chibás al cumplirse cien años de su natalicio Fidel Castro Ruz Pág. 9 Eduardo Chibás: Vergüenza contra dinero Armando Hart Dávalos Pág. 16 El chibasismo ortodoxo: implicaciones y perspectivas Elena Alavez Pág. 21 • AÑO 9 8, No. 3-4, JULIO-DICIEMBRE 2007 ISSN 0006-1727 RNPS 0383 EVISTA DE LA BIBLIOTECA NACIONAL JOSÉ MARTÍ 1 Año 98 / Cuarta Época Julio-Diciembre, 2007 Número 3-4 Ciudad de La Habana ISSN 0006-1727 RNPS 0383 Director: Eduardo Torres Cuevas Consejo de honor In Memoriam: Ramón de Armas, Salvador Bueno Menéndez, Eliseo Diego, María Teresa Freyre de Andrade, Josefina García Carranza Bassetti, René Méndez Capote, Manuel Moreno Fraginals, Juan Pérez de la Riva, Francisco Pérez Guzmán Consejo de redacción: Eliades Acosta Matos, Rafael Acosta de Arriba, Ana Cairo Ballester, Tomás Fernández Robaina, Fina García Marruz, Zoila Lapique Becali, Enrique López Mesa, Jorge Ibarra Cuesta, Siomara Sánchez Roberts, Emilio Setién Quesada, Carmen Suárez León, Cintio Vitier Jefa de redacción: Araceli García Carranza Edición y Composición electrónica: Marta Beatriz Armenteros Toledo Idea original de diseño de cubierta: Luis J. Garzón Versión de diseño de cubierta: José Luis Soto Crucet Cubierta: Foto de Eduardo Chibás Ribas Viñetas: Ediciones de El ingenioso hidalgo don Quijote de la Mancha de la Biblioteca Nacional José Martí Canje: Revista de la Biblioteca Nacional José Martí Plaza de la Revolución Ciudad de La Habana Fax: 881 2428 Email: [email protected] En Internet puede localizarnos: www.bnjm.cu Primera época 1909-1912. -

Orders, Decorations, and Medals of the Republic of Cuba Dr, K, G, Klietmann, Director Df the Institute for Scientific Orders Research

ORDERS, DECORATIONS, AND MEDALS OF THE REPUBLIC OF CUBA DR, K, G, KLIETMANN, DIRECTOR DF THE INSTITUTE FOR SCIENTIFIC ORDERS RESEARCH Cuban revolutionaries began their fight against Batista’s dicta- torsh~p by an attack on the Moncada Barracks on 26 July 1953 under the leadership of Fidel Castro. Victory was won on 1 January 1959 with the dictator fleeing into exile. During the first months of 1959 no awards were created. Only two laws concerning decorations were passed in Fidel Castro’s first year of power. Law No. 586, dated 7 October 1959, modified the statutes of the Order "Carlos Manuel de C~spedes" while Law No. 642, dated 20 November 1959, decreed a verification of the awards of the Order "De Merito Mambi," issued up to 31 December 1958. After Fidel Castro announced the socialist character of the Cuban revolutxon on 16 April 1961, the introduction of a new Cuban decoration system was initiated. By virtue of the Fundamental Law No. 17, dated 28 June 1978, the National Assembly of the People’s Chamber defined the decoration system of the Republic of Cuba. By means of the law-decree dated i0 December 1979 (No. 30) the State Council gave its approval. By 1984 there were approximately two Honorary Titles, 19 Orders, 30 Decorations, and 35 Medals in existence. Tl~e bestowal of decorations to Cubans and foreign nationals ~s done by decxsion of the State Councxl on a recommendation by the respective social organization. In the following, an overview on the orders, decorations, and medals known to the author is to be gxven. -

Guide to Cuban Law and Legal Research

International Journal of Legal Information 45.2, 2017, pp. 76–188. © The Author(s) 2017 doi:10.1017/jli.2017.22 GUIDE TO CUBAN LAW AND LEGAL RESEARCH JULIENNE E. GRANT,MARISOL FLORÉN-ROMERO,SERGIO D. STONE,STEVEN ALEXANDRE DA COSTA,LYONETTE LOUIS-JACQUES,CATE KELLETT, JONATHAN PRATTER,TERESA M. MIGUEL-STEARNS,EDUARDO COLÓN-SEMIDEY,JOOTAEK LEE,IRENE KRAFT AND YASMIN MORAIS1 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Julienne E. Grant LEGAL SYSTEM AND GOVERNMENT STRUCTURE Steven Alexandre da Costa and Julienne E. Grant A. HISTORICAL OVERVIEW B. TRANSITION TO THE CURRENT LEGAL LANDSCAPE C. CURRENT LEGAL LANDSCAPE D. THE CUBAN GOVERNMENT: A BRIEF OVERVIEW E. SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY THE CONSTITUTION Lyonette Louis-Jacques A. INTRODUCTION B. THE 1976 CONSTITUTION AND ITS AMENDMENTS C. FUTURE D. CONSTITUTIONAL TEXTS E. CONSTITUTIONAL COMMENTARIES F. CURRENT AWARENESS G. SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY EXECUTIVE POWERS Julienne E. Grant A. THE COUNCIL OF STATE B. THE COUNCIL OF MINISTERS C. FIDEL CASTRO’S ROLE: POST-2007 D. RESEARCHING THE COUNCILS OF STATE AND MINISTERS IN SPANISH E. RESEARCHING THE COUNCILS OF STATE AND MINISTERS IN ENGLISH F. SOURCES FOR THE CASTROS’ SPEECHES, INTERVIEWS AND WRITINGS LEGISLATION AND CODES Marisol Florén-Romero and Cate Kellett A. OFFICIAL GAZETTE B. COMPILATIONS OF LAWS C. CODES D. ENGLISH-LANGUAGE TRANSLATIONS OF CUBAN LAWS E. ONLINE RESOURCES FOR CODES AND LEGISLATION F. SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY OF LEGISLATION, CODES AND COMMENTARY 1 © 2017 Julienne E. Grant, Marisol Florén-Romero, Sergio D. Stone, Steven Alexandre da Costa, Lyonette Louis-Jacques, Cate Kellett, Jonathan Pratter, Teresa M. Miguel-Stearns, Eduardo Colón-Semidey, Jootaek Lee, Irene Kraft and Yasmin Morais. 76 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. -

Reseñas Biográficas De Figuras Significativas En La Historia De Cuba (Segunda Parte)

Reseñas biográficas de figuras significativas en la historia de Cuba (Segunda parte) Manual didáctico para docentes y estudiantes Autores: Dr. Raúl Quintana Suárez Lic. Bernardo Herrera Martín 1 ¿Qué nos proponemos con este libro? No es nuestro objetivo el realizar aportes sustanciales a la investigación pedagógica sino el facilitar a maestros, profesores y estudiantes de los diferentes niveles de enseñanza, un instrumento didáctico que facilite su labor docente educativa. Con esta obra los docentes contarán con un material asequible, como material de consulta, en la conmemoración de efemérides, en la preparación de sus clases e incluso en su propia superación profesional Las reseñas biográficas han sido tomadas de diversas fuentes, que se mencionan en la bibliografía consultada, con determinadas adaptaciones imprescindibles en su redacción y contenido, acorde al objetivo de la obra. Su principal propósito es ofrecer más de 150 síntesis biográficas de figuras de la política, de la ciencia y de la cultura en su más amplio concepto, que han tenido significativa participación en el decursar histórico de nuestra patria, por sus aportes a la creación de nuestra identidad nacional. No todas ellas han desempeñado un papel progresista, pero no es posible excluirlas de este recuento, dada su participación en etapas concretas de nuestra historia. No se pretende incluirlas a todas, ni siquiera a la mayoría, pues resultaría una tarea enciclopédica que rebasaría las posibilidades de este libro. Estamos conscientes que faltan figuras descollantes, en esferas tales como la pedagogía, educación, cultura, política y deportes, así como la de los miles de cubanos que ofrendaron sus vidas en distintas épocas y contextos históricos, en aras de la defensa de nuestra soberanía, misiones internacionalistas, víctimas de acciones terroristas u otras acciones meritorias. -

The Invisible Government

Date: 4/5/2011 Page: 1 of 237 THE INVISIBLE GOVERNMENT by David Wise and Thomas B. Ross © Copyright 1964, by David Wise and Thomas B. Ross The Invisible Government, by Tara Carreon Molehunt, by David Wise Table of Contents 1. The Invisible Government 2. 48 Hours Date: 4/5/2011 Page: 2 of 237 3. Build-Up 4. Invasion 5. The Case of the Birmingham Widows 6. A History 7. Burma: The Innocent Ambassador 8. Indonesia: "Soldiers of Fortune" 9. Laos: The Pacifist Warriors 10. Vietnam: The Secret War 11. Guatemala: CIA's Banana Revolt 12. The Kennedy Shake-up 13. The Secret Elite 14. The National Security Agency 15. The Defense Intelligence Agency 16. CIA: "It's Well Hidden" 17. CIA: The Inner Workings 18. The Search for Control 19. Purity in the Peace Corps 20. A Gray Operation 21. Missile Crisis 22. Electronic Spies 23. Black Radio 24. CIA's Guano Paradise 25. The 1960 Campaign -- And Now 26. A Conclusion Notes Indexhttp://www.american-buddha.com/invisiblegov.toc.htm Date: 4/5/2011 Page: 3 of 237 THE INVISIBLE GOVERNMENT -- THE INVISIBLE GOVERNMENT THERE ARE two governments in the United States today. One is visible. The other is invisible. The first is the government that citizens read about in their newspapers and children study about in their civics books. The second is the interlocking, hidden machinery that carries out the policies of the United States in the Cold War. This second, invisible government gathers intelligence, conducts espionage, and plans and executes secret operations all over the globe.