Submission on Regional Development And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City of Greater Shepparton ID Report

City of Greater Shepparton 2011 Census results Comparison year: 2006 Benchmark area: Regional VIC community profile Compiled and presented in profile.id®. http://profile.id.com.au/shepparton Table of contents Estimated Resident Population (ERP) 2 Population highlights 4 About the areas 6 Five year age groups 9 Ancestry 12 Birthplace 15 Year of arrival in Australia 17 Proficiency in English 19 Language spoken at home 22 Religion 25 Qualifications 27 Highest level of schooling 29 Education institution attending 32 Need for assistance 35 Employment status 38 Industry sectors of employment 41 Occupations of employment 44 Method of travel to work 47 Volunteer work 49 Unpaid care 51 Individual income 53 Household income 55 Households summary 57 Household size 60 Dwelling type 63 Number of bedrooms per dwelling 65 Internet connection 67 Number of cars per household 69 Housing tenure 71 Housing loan repayments 73 Housing rental payments 75 SEIFA - disadvantage 78 About the community profile 79 Estimated Resident Population (ERP) The Estimated Resident Population is the OFFICIAL City of Greater Shepparton population for 2012. Populations are counted and estimated in various ways. The most comprehensive population count available in Australia is derived from the Census of Population and Housing conducted by the Australian Bureau of Statistics every five years. However the Census count is NOT the official population of the City of Greater Shepparton. To provide a more accurate population figure which is updated more frequently than every five years, the Australian Bureau of Statistics also produces "Estimated Resident Population" (ERP) numbers for the City of Greater Shepparton. See data notes for a detailed explanation of different population types, how they are calculated and when to use each one. -

GOULBURN the Goulburn Region Although the Goulburn Region Makes up Only 12% of Victoria’S Area It Goulburn Encompasses Some of Victoria’S Most Productive Land

DEPARTMENT OF PRIMARY INDUSTRIES GOULBURN The Goulburn region Although the Goulburn region makes up only 12% of Victoria’s area it Goulburn encompasses some of Victoria’s most productive land. Goulburn The region has a temperate climate with excellent access to water resources combined with a variety of soil types and microclimates. The area’s rich natural resources have fostered the development of Located in the north of the State, some of the most productive agricultural enterprises in Australia. the Goulburn region is often described as the 'food bowl' A huge range of quality food products are continually harvested such of Victoria. as milk, deciduous fruits, grains, beef, oilseeds and many more. Some of the world’s most successful food companies plums, nectarines, nashi, kiwi fruit, oranges, lemons, are located in the region and there are now more than limes and cherries. 20 factories processing regional farm produce. In In response to the changing global marketplace, the excess of $630 million has been invested in food industry has developed intensive, high density planting processing infrastructure during the past few years. systems to produce early yielding, good quality, price The Goulburn region provides significant competitive fruit. The resulting additional tonnages are opportunities for investment, economic growth and available for export markets, mainly in South East Asia. export development. There are approximately 50 orchardists with packing The Goulburn region is home to a significant sheds licensed by the Australian Quarantine and proportion of the State’s biodiversity, internationally Inspection Service to pack fresh fruit for export and recognised wetlands, nature reserves and forests. -

Shepparton, Victoria

Full version of case study (3 of 3) featured in the Institute for the Study of Social Change’s Insight Report Nine: Regional population trends in Tasmania: Issues and options. Case study 3: Shepparton, Victoria Prepared by Institute for the Study of Social Change Researcher Nyree Pisanu Shepparton is a region in Victoria, Australia with a total population of 129,971 in 2016 (ABS, 2019). The Shepparton region includes three local government areas, including Greater Shepparton, Campaspe and Moira. In 2016, the regional city of Shepparton-Mooroopna had a population of 46,194. The Greater City of Shepparton had a population of 65,078 in 2018, with an average growth rate of 1.14% since 2011. The median age in Shepparton is 42.2 and the unemployment rate is 5.7%. In 2016, There were more births than deaths (natural increase= 557) and in-migration exceeded out- migration (net migration = 467). Therefore, natural increase is driving Shepparton’s population growth (54%). Economic profile The Shepparton region is located around 180kms north of Melbourne (Goulburn Broken Catchment Management Authority, 2016). The region is known as the Shepparton Irrigation Region as it is located on the banks of the Goulburn river, making it an ideal environment for food production (Goulburn Broken Catchment Management Authority, 2016). Shepparton’s top three agricultural commodities are sheep, dairy and chickens (ABS, 2019). The region is at the heart of the ‘food bowl of Australia’, also producing fruit and vegetables. The region also processes fruit, vegetables and dairy through large processing facilities for both consumption and export (Regional Development Victoria, 2015). -

07 FEB 2020 Shepparton and Wangaratta to Host Climate Change

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA Environment and Planning Standing Committee – Legislative Assembly MEDIA RELEASE Shepparton and Wangaratta to host climate change hearings The parliamentary inquiry into tackling climate change in Victorian communities continues next week with public hearings and site visits in Shepparton and Wangaratta on 12 and 13 February. The Legislative Assembly’s Environment and Planning Committee will meet with local councils, sustainability groups and community organisations to discuss regional responses to climate change and what the government can do to help communities take action. “We know that regional communities are often highly innovative and active when it comes to sustainability, waste management and recycling, agroforestry and renewable energy projects,” said Committee Chair Darren Cheeseman. “We want to hear from members of the Shepparton and Wangaratta communities, learn more about what they’re doing to mitigate climate change and understand how the government can support them,” he said. The Shepparton hearing on 12 February is at the Mooroopna Education and Activity Centre, 23 Alexandra Street, Mooroopna from 10:30 am to 1:15 pm. The Committee will then visit the Violet Town Community Forest and meet with local sustainability groups at the Violet Town Community Complex. The Wangaratta hearing on 13 February is at Wangaratta Regional Study Centre, GoTafe and Charles Sturt University, 218 Tone Road, Wangaratta from 9:30 am to 12:15 pm. A site visit with Totally Renewable Yackandandah to discuss the group’s community energy projects will follow. Appearing before the Committee in Shepparton will be several local councils, the North East Region Sustainability Alliance (NERSA) and Benalla Sustainable Future Group. -

Murchison Pow Camp Ed Recommendation

1 Recommendation of the Executive Director and assessment of cultural heritage significance under Part 3 of the Heritage Act 2017 Name Murchison Prisoner of War Camp Location 410-510 Wet Lane, Murchison, City of Greater Shepparton Provisional VHR Number PROV VHR2388 Provisional VHR Categories Registered Place, Registered Archaeological Place Hermes Number 5592 Heritage Overlay Greater Shepparton, HO57 (individual) Murchison Prisoner of War Camp, Southern Cell Block, October 2017 EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR RECOMMENDATION TO THE HERITAGE COUNCIL: • That Murchison Prisoner of War Camp be included as a Registered Place and a Registered Archaeological Place in the Victorian Heritage Register under the Heritage Act 2017 [Section 37(1)(a)]. STEVEN AVERY Executive Director Recommendation provided to the Heritage Council of Victoria: 12 July 2018 Recommendation publicly advertised and available online: From 20 July 2018 for 60 days This recommendation report has been issued by the Executive Director, Heritage Victoria under s.37 of the Heritage Act 2017. It has not been considered or endorsed by the Heritage Council of Victoria. Name: Murchison Prisoner of War Camp Hermes Number: 5592 2 EXTENT OF NOMINATION Date that the nomination was accepted by the Executive Director 19 November 1998 Written extent of nomination Murchison Prisoner of War Camp is identified in the Greater Shepparton Heritage Study. The place has an individual heritage overlay, HO57. Nomination extent diagram Is the extent of nomination the same as the recommended extent? Yes Name: Murchison Prisoner of War Camp Hermes Number: 5592 3 RECOMMENDED REGISTRATION All of the place shown hatched on Diagram 2388 encompassing all of Lot 2 on Lodged Plan 113159, all of Lot 1 on Lodged Plan 113159, part of Lot 4 on Plan of Subdivision 439182, and Part of Lot 1 on Plan of Subdivision 439182. -

Settlement Engagement and Transition Support (SETS)

Settlement Engagement and Transition Support (SETS) - Successful Applicants Note: The final list of providers is subject to Funding Agreement negotiations with successful applicants. State/Territory of LEGAL ENTITY NAME Service Area/s Service Area/s Client Services Access Community Services Ltd QLD Gold Coast, Ipswich, Logan - Beaudesert African Women's Federation of SA Inc SA Adelaide - North, Adelaide - South, Adelaide - West Albury-Wodonga Volunteer Resource Bureau Inc NSW & VIC Albury (NSW), Wodonga (VIC) Anglicare N.T. Ltd NT Darwin Anglicare SA Ltd SA Adelaide - North Arabic Welfare Inc VIC Brunswick - Coburg, Moreland - North, Tullamarine - Broadmeadows, Whittlesea - Wallan Asian Women at Work Inc NSW Auburn, Bankstown, Blacktown, Canterbury, Fairfield, Hurstville Assyrian Australian Association NSW Blacktown, Ryde, Sydney South West Australian Afghan Hassanian Youth Association Inc NSW NSW Australian Muslim Women's Centre for Human Rights Inc VIC Melbourne - Inner, Melbourne - North East, Melbourne - North West, Melbourne - South East, Melbourne - West Australian Refugee Association Inc SA Adelaide - Central and Hills, Adelaide - North, Adelaide - South, Adelaide - West Ballarat Community Health VIC Ararat Region, Ararat, Ballarat Bendigo Community Health Services Ltd VIC Bendigo Brisbane South Division Ltd QLD Brisbane - East, Brisbane - North, Brisbane - South, Brisbane - West, Brisbane - Inner City Bundaberg & District Neighbourhood Centre Inc QLD Bundaberg CatholicCare Victoria Tasmania VIC & TAS TAS: Hobart VIC: Melbourne -

Shepparton & Mooroopna 2050

Shepparton & Mooroopna 2050 Regional City Growth Plan July 2020 Acknowledgement of Traditional Owners Tables Table 1 Industrial growth areas 21 We acknowledge the traditional owners of the land which now comprises Greater Shepparton, we pay respect to their tribal elders, we celebrate their continuing culture and we acknowledge the memory Table 2 Current residential growth areas 30 of their ancestors. Table 3 Investigation areas considered for residential growth 31 Table 4 Future residential growth areas 32 Contents Figures Executive Summary 5 Figure 1 Greater Shepparton population by age cohort 2016 – 2036 11 A Growth Plan for Shepparton and Mooroopna 6 Figure 2 Victorian regional cities components of population change 2016 12 Introduction 9 Figure 3 Greater Shepparton unemployment rate 2010 – 2018 12 Vision 15 Figure 4 Service hub 18 Principles 16 Figure 5 Shepparton CBD precincts and renewal opportunities 38 Outcomes 17 Figure 6 Mooroopna opportunities 41 Outcome 1 – A City for the Goulburn Region 19 Figure 7 Economic resilience road maps 58 Outcome 2 – A City of Liveable Neighbourhoods 24 Outcome 3 – A City of Growth and Renewal 30 Outcome 4 – A City with Infrastructure and Transport 42 Outcome 5 – A City that is Greener and Embraces Water 50 Outcome 6 – A City of Innovation and Resilience 54 Acronyms Implementing the Vision 59 ACZ Activity Centre Zone Council Greater Shepparton City Council CBD Central Business District CVGA Central Victorian Greenhouse Alliance Plans GVWRRG Goulburn Valley Waste and Resource Recovery Group Plan 1 -

Shepparton Line Upgrade – Stage 2

SHEPPARTON Shepparton Line Upgrade – Stage 2 The Victorian Government is upgrading the Shepparton Line to deliver more reliable services and allow modern VLocity trains to travel to and from Shepparton for the first time. Work on the Shepparton Line Upgrade is Delivering benefits for Shepparton underway with $356 million invested in the first Line passengers two stages of the project — an unprecedented investment in this part of Victoria’s regional Stage 2 of the Shepparton Line Upgrade will train network. provide the infrastructure required for VLocity trains to run to Shepparton for the first time, The Shepparton Line Upgrade will deliver the improving service reliability and providing best outcomes for passengers along the Shepparton passengers with more comfortable journeys. Line and maximise efficiencies while minimising disruption to passenger services. This includes a new stabling facility to house the trains as well as level crossing upgrades Stage 1, which is now complete, included: between Donnybrook and Shepparton to ensure they're compatible with VLocity trains and to boost — 10 extra train services a week between safety for road users and train passengers. Melbourne and Shepparton The crossing loop extension will improve service — a stabling upgrade at Shepparton Station reliability by giving trains more opportunities to — 29 extra coach services between pass each other. Shepparton and Seymour. Rail Projects Victoria is continuing detailed Stage 2 includes: investigations and planning for Stage 3 of the Shepparton Line Upgrade, to assess the upgrades — platform extensions at Mooroopna, Murchison required to deliver nine return services a day East and Nagambie stations for Shepparton. — a crossing loop extension near Murchison East — 59 level crossing upgrades between Donnybrook and Shepparton — stabling to house VLocity trains — a business case to finalise the scope and costs to deliver nine return services a day between Shepparton and Melbourne. -

Vic Bus Goulburn Valley

VB14 SHEPPARTON - COBRAM - GRIFFITH For trains and additional buses Shepparton-Melbourne see VC3. Ap19 Some buses connect at Shepparton with VC5 or Seymour with VC4. Connects at Griffith with NC6, NB20 and NB22. TRAIN M-F M-F M-F M-F Sa & SuO MELBOURNE STHRN. CROSS 933 1432 1631 1908 912 1832 SEYMOUR arr 1055 1554x 1805 2029 1034 1951 dp 1100 1610 1810 2034 1039 1956 SHEPPARTON arr 1210x 1922x 2146x 1149x 2106x BUS dp 1220 1735 1935 2155 1200 2115 Numurkah 1245 1813 2005 2225 1235 2145 COBRAM 1315 1845 2037 2257 1305 2215 TOCUMWAL 1905 2058 2318 2236 Jerilderie 2147 2324 GRIFFITH 2323 059 M-F M-F M-F M-F M-F SaO SaO SuO SuO GRIFFITH 215 245 1155 Jerilderie 350 420 1330 TOCUMWAL 330 439 630 509 1419 COBRAM 351 500 715 900 1425 530 1445 545 1440 Numurkah 426 535 750 930 1455 605 1515 620 1515 SHEPPARTON arr 500x 610x 830 1015x 1535x 640x 1550x 700x 1545x TRAIN dp 510 628 845 1040 1605 716 1604 716 1604 SEYMOUR arr 1015x 1200x TRAIN dp 637 734 1034 1214 1710 822 1710 822 1710 MELBOURNE 759 910 1154 1335 1835 948 1829 948 1829 SOUTHERN CROSS 172 VB15 MELBOURNE-BARHAM / BARMAH / ECHUCA-DENILIQUIN VIA BENDIGO, VIA HEATHCOTE, & VIA SHEPPARTON For Rail service Bendigo - Echuca see table VC7. Ap19 Connects at Shepparton with VC5. Connects at Bendigo with VC6. For Countrylink buses Deniliquin-Echuca see table NB22. TRAIN M-F M-F FO M-F MSaO M-F M-F MELBOURNE SOUTHERN CROSS 613 932 1150 1215 1240 1252 1252 BENDIGO arr 816x 1404x dp 845 1415 Heathcote 1325 1415 Rochester 940 1415 1510 1500 MURCHISON EAST arr 1135x BUS dp 1140 SHEPPARTON arr 1525x1525x dp 15401535 Tatura 1158 1605 Kyabram 1225 1635 Nathalia 1612 BARMAH 1635 ECHUCA R.S. -

Bendigo to Albury Via Shepparton, Wangaratta and Wodonga

Bendigo – Albury AD Effective 31/01/2021 Bendigo to Albury via Shepparton, Wangaratta and Wodonga Mon, Wed Daily Friday Daily Service COACH COACH COACH COACH Service Information ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ BENDIGO LA TROBE UNI (1) dep 17.21 Bendigo La Trobe Uni (2) 17.26 BENDIGO dep 11.35 17.51 Elmore (1) 12.15 18.31 Corop 12.30 18.46 Stanhope 12.45 19.01 MOOROOPNA dep 13.10 17.30 19.26 20.10 Shepparton 13.20 17.45 19.31 20.20 Benalla 14.05 – 20.16 21.05 WANGARATTA arr 14.40 – 20.51 – Change Service TRAIN TRAIN Service Information ƒç ƒç WANGARATTA dep 14.50 – 21.01 21.35 Springhurst 15.05 – 21.16 – Chiltern 15.15 – 21.26 – Wodonga 15.32 20.35 21.43 22.25 ALBURY arr 15.55 20.50 22.05 22.35 Albury to Bendigo via Wodonga, Wangaratta and Shepparton Daily Monday Wed, Fri Daily Service COACH TRAIN TRAIN COACH Service Information ∑ ƒç ƒç ∑ ALBURY dep 04.25 06.35 06.35 07.00 Wodonga 04.35 06.44 06.44 07.15 Chiltern – 07.01 07.01 – Springhurst – 07.11 07.11 – WANGARATTA arr – 07.27 07.27 – Change Service COACH COACH Service Information ∑ ∑ WANGARATTA dep 05.25 07.37 07.37 – Benalla 05.55 08.07 08.07 – Shepparton 06.35 08.57 08.57 10.15 MOOROOPNA arr 06.43 09.02 09.02 10.30 Stanhope 09.27 09.27 Corop 09.42 09.42 Elmore (2) 09.52 09.52 BENDIGO arr 10.37 10.37 BENDIGO LA TROBE UNI (1) arr 10.42 ƒ – First Class / ç – Catering / ∑ – Wheelchair accessible / Coach services shown in red / £ Reservations required / £ Friday only Altered timetables may apply on public holidays. -

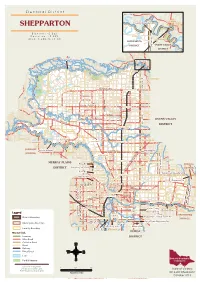

SHEPPARTON Propertyproperty Boundaryboundary

E l e c t o r a l D i s t r i c t InsetInsetInset mapmapmap TOCUMWALTOCUMWAL SHEPPARTON PropertyProperty BoundaryBoundary E l e c t o r s : 4 5 , 3 6 2 S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S D e v i a t i o n : + 9 . 3 8 % MYWEEMYWEE S S S S S S S t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o k k k k k k k k k k k k k k k k k k k k k k k k k k k k k k k k k k k k k k k k k k A r e a : 3 , 2 8 8 . 4 6 s q k m k k k k k k k KOONOOMOOKOONOOMOO e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e s s s s s s s s s s s s s s s s s s s s s SHEPPARTONSHEPPARTON s s s s s s s SHEPPARTONSHEPPARTON s s s s s s s SHEPPARTONSHEPPARTON s s s s s s s SHEPPARTONSHEPPARTON s s s s s s s R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d DISTRICTDISTRICT d d d d d d d OVENSOVENS VALLEYVALLEY DISTRICTDISTRICT MurrayMurray RiverRiver SeeSee insetinset mapmap MYWEEMYWEE ULUPNAULUPNA MYWEEMYWEE S S S S S S S S Barmah S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t t State Park t t t t t t t KOONOOMOOKOONOOMOO o o o o o o o KOONOOMOOKOONOOMOO o o o o o o o KOONOOMOOKOONOOMOO o -

Student Handbook

STUDENT HANDBOOK gotafe.vic.edu.au 1 2 CONTENTS Campuses 4- 7 Student Welfare Unit 9 - 13 GOTAFE A-Z 14 - 27 Contacts 31 IMPORTANT NAMES AND NUMBERS TO REMEMBER COURSE COORDINATOR TEACHER Name: Name: Email: Email: Ph: Ph: STUDENT WELFARE UNIT CONTACT PERSON CONTACT PERSON Name: Name: Email: Email: Ph: Ph: 3 CAMPUSES MACKELLAR STREET CHURCH STREET SMYTHE STREET SAMARIA ROAD HANNAH STREET BENALLA STREET BRIDGE STREET SALISBURY STREET CARRIER STREET RAILWAY PLACE NUNN STREET COSTER STREET ARUNDEL STREET Benalla Campus Samaria Road, Benalla The Benalla Campus is a modern building with excellent facilities including Clinical Skills Laboratories with patient simulation for our Health students. GOULBOURN VALLEY HWY WALLIS STREET ST PRESIDENT HIGH STREEET HIGH STREEET BUTLER STREEET ELIZABETH STREET WALLIS STREET BISHOP STREEET TRISTAN STREEET TALLAROOK STREET CRAWFORD STREEET CRAWFORD SeymourWILLIAM STREEET Campus WALLIS STREETWallis Street, Seymour Seymour Campus is located in the heart of STATIONSeymour STREEET and is easily accessed via regular train and bus services. Students benefit from a modern environment with access to the latest technology and enjoy a friendly and welcoming atmosphere. 4 D A O R D R O F D N A S T E E R T S G N I N W O R B MASON STREET SHANLEY STREET R D E S I R P R E T N E D A O R E N O T Wangaratta Regional Study Centre Tone Road, Wangaratta GRAVEL PIT ROAD The Wangaratta Regional Study Centre is a world class facility developed in partnership with Charles Sturt University (CSU). This facility caters to the needs of the animal science, agriculture, equine, horticulture and viticulture industries.