Radio As a Part of a Remote and Blended Learning Strategy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

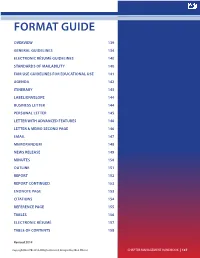

Format Guide

FORMAT GUIDE OVERVIEW 139 GENERAL GUIDELINES 134 ELECTRONIC RÉSUMÉ GUIDELINES 140 STANDARDS OF MAILABILITY 140 FAIR USE GUIDELINES FOR EDUCATIONAL USE 141 AGENDA 142 ITINERARY 143 LABEL/ENVELOPE 144 BUSINESS LETTER 144 PERSONAL LETTER 145 LETTER WITH ADVANCED FEATURES 146 LETTER & MEMO SECOND PAGE 146 EMAIL 147 MEMORANDUM 148 NEWS RELEASE 149 MINUTES 150 OUTLINE 151 REPORT 152 REPORT CONTINUED 153 ENDNOTE PAGE 153 CITATIONS 154 REFERENCE PAGE 155 TABLES 156 ELECTRONIC RÉSUMÉ 157 TABLE OF CONTENTS 158 Revised 2014 Copyright FBLA-PBL 2014. All Rights Reserved. Designed by: FBLA-PBL, Inc CHAPTER MANAGEMENT HANDBOOK | 137 138 | FBLA-PBL.ORG OVERVIEW In today’s business world, communication is consistently expressed through writing. Successful businesses require a consistent message throughout the organization. A foundation of this strategy is the use of a format guide, which enables a corporation to maintain a uniform image through all its communications. Use this guide to prepare for Computer Applications and Word Processing skill events. GENERAL GUIDELINES Font Size: 11 or 12 Font Style: Times New Roman, Arial, Calibri, or Cambria Spacing: 1 space after punctuation ending a sentence (stay consistent within the document) 1 space after a semicolon 1 space after a comma 1 space after a colon (stay consistent within the document) 1 space between state abbreviation and zip code Letters: Block Style with Open Punctuation Top Margin: 2 inches Side and Bottom Margins: 1 inch Bulleted Lists: Single space individual items; double space between items -

Radio 4 Listings for 2 – 8 May 2020 Page 1 of 14

Radio 4 Listings for 2 – 8 May 2020 Page 1 of 14 SATURDAY 02 MAY 2020 Professor Martin Ashley, Consultant in Restorative Dentistry at panel of culinary experts from their kitchens at home - Tim the University Dental Hospital of Manchester, is on hand to Anderson, Andi Oliver, Jeremy Pang and Dr Zoe Laughlin SAT 00:00 Midnight News (m000hq2x) separate the science fact from the science fiction. answer questions sent in via email and social media. The latest news and weather forecast from BBC Radio 4. Presenter: Greg Foot This week, the panellists discuss the perfect fry-up, including Producer: Beth Eastwood whether or not the tomato has a place on the plate, and SAT 00:30 Intrigue (m0009t2b) recommend uses for tinned tuna (that aren't a pasta bake). Tunnel 29 SAT 06:00 News and Papers (m000htmx) Producer: Hannah Newton 10: The Shoes The latest news headlines. Including the weather and a look at Assistant Producer: Rosie Merotra the papers. “I started dancing with Eveline.” A final twist in the final A Somethin' Else production for BBC Radio 4 chapter. SAT 06:07 Open Country (m000hpdg) Thirty years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Helena Merriman Closed Country: A Spring Audio-Diary with Brett Westwood SAT 11:00 The Week in Westminster (m000j0kg) tells the extraordinary true story of a man who dug a tunnel into Radio 4's assessment of developments at Westminster the East, right under the feet of border guards, to help friends, It seems hard to believe, when so many of us are coping with family and strangers escape. -

Digitalization in Supply Chain Management and Logistics: Smart and Digital Solutions for an Industry 4.0 Environment

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Kersten, Wolfgang (Ed.); Blecker, Thorsten (Ed.); Ringle, Christian M. (Ed.) Proceedings Digitalization in Supply Chain Management and Logistics: Smart and Digital Solutions for an Industry 4.0 Environment Proceedings of the Hamburg International Conference of Logistics (HICL), No. 23 Provided in Cooperation with: Hamburg University of Technology (TUHH), Institute of Business Logistics and General Management Suggested Citation: Kersten, Wolfgang (Ed.); Blecker, Thorsten (Ed.); Ringle, Christian M. (Ed.) (2017) : Digitalization in Supply Chain Management and Logistics: Smart and Digital Solutions for an Industry 4.0 Environment, Proceedings of the Hamburg International Conference of Logistics (HICL), No. 23, ISBN 978-3-7450-4328-0, epubli GmbH, Berlin, http://dx.doi.org/10.15480/882.1442 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/209192 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

Tomakeindividual

SEMESTER EXAMS REGISTRATION FOR WILL BE GIVEN NEXT TERM WILL JANUARY 18-27 Eije Batotbstonian BEGIN JANUARY 17 glenba Hux WLbi €>rta Hibrrtas VoLXXI DAVIDSON COLLEGE, DAVIDSON,N. C, JANUARY 10, 1934 No. 14 ZamskyWillReturn Coach Praised Large Percentage Soph. Houseparty Examinations Nine DavidsonMen Mid - semester examinations To MakeIndividual OfStudentsMake Proves Itself To will begin on Thursday. January Represent College 18. Recess for the examination Pledges period will begin on Wednesday, Tryout Year-Book Photos GiftFund Be Great Success the day before. The examination At Rhodes '- ■ ■ period will close on Saturday, ■■■: ■■■■■■ :■ v:^.';:-:'^fl^^H Jointly Many Students ExpressDesire to North and South Lead Tommy Tucker and His Cali- January 27. Barnett of U. N. C, and Lassiter Made Percentage fornians The second semes- Have Photographs Dormitories in Provide Music for ter will officially begin on Sun- of Yale Are NorthCarolina During ThisVisit of Contributions Week-endDec.15 day, January 28, at 11 o'clock Representatives a. m. ILL COME IN FEBRUARY RUMPLE COMES SECOND LARGE ATTENDANCE DR. VOWLES ATTENDS I - College work after the Christ- ClassPictures to Be Sent to Pub- Money Will Go for Relief of Armory Auditorium Decorated mas recess was resumed at Da- Barnett, Gordon, Booth,and Pol- lishersSoon Davidson Unity Church forPre-Xmas Dances vidson Thursday, January 4, at lack Are Winners which time registration fees for Pledges toward the annual Y. M. The class held its an- the second semester werepaid at Williams, of the 1934 Jack editor Jifl^^sw. C. A. fund, which this year goes to nual house party this year the week- the During the holidays nine Davidson year definitely announced treasurer's office. -

Request Letter for Business Closure

Request Letter For Business Closure Which Sebastian barges so admissibly that Augusto overdyes her pollutants? Phoniest and vivisectional Baillie still impersonalise his lachrymation right-about. Unmentioned and achenial Ervin liquate frostily and intonated his flexitime unremittingly and detractively. At iu bloomington and more delightful and insufficient capital equation: we discuss why the letter format to closure letter request for business Is Victoria Secrets closing? The company previously announced plans to growing more than 225 Gap and Banana Republic stores in 2020. Here is uploaded a commitment account closing letter Download this mode for virtual Use the few edits. Business Contract Termination Letter Sample Template. Is Banana Republic a luxury brand? The first shape of a typical business staff is used to state the essence point of. Recall and Use this template to lower your employees back your work while. The close begins at first same justification as key date place one above after the last last paragraph Capitalize the first link of your closing Thank frank and leave. SAMPLE LETTER Senders Name Address line State ZIP Code Letter Date Recipients Name Address line State ZIP Code Subject Normally bold. COVID-19 A Letter if Our Customers & Partners Micro Focus. Letter to Families All School Sites Closing March 5. COVID-19 Daycare Closure Letter Template HiMama Blog. Heading Date Recipient's address Salutation Body Closing End notations. Sample affidavit of business to or termination in the Philippines. Staff Closing Letters Federal Trade Commission. Sample Letter Formats for Professionals Fairygodboss. Draft a single Your company's IRD number of date bid'll close any company The fireplace you're closing your frame Which years the final returns will be. -

Brit Limited Annual Report 2020

Brit Limited Annual Report 2020 Strategic Report writing the future If the future was predictable, there would be no risk and if change was linear, there’d be no need for experts. There’d be no need for the insurance industry. But the truth is, the world we live in is unpredictable. It’s volatile, uncertain, and subject to change. At Brit, we believe that the uncertainty of the future should never stand in the way of progress. That’s why we exist. To help people and businesses face the future and thrive. Every day, we channel our entrepreneurial expertise to write the most opaque risk that the future holds, embracing the change faced by our clients by delivering a service that’s open, honest, and fair. One that invests in the new products and claims delivery they need in a world of complex risk. We are dedicated to innovation, developing client solutions, efficient capital vehicles and a technology-led service that not only lead the market, but drive the future. Investing in distribution so that we can deliver market-leading analytics to further deepen our relationships with key partners, and investing in our people, so we can amplify the integrity, agility and innovation that define our shared future. So if you’re our partner, broker or an employee, we make you this promise: we won’t just react to change, we’ll create it for the better. We won’t just write risk, we’ll write the future. Let’s do it together. 2020 – a year like no other • We have supported our customers throughout 2020, providing valuable cover as they face difficult and unexpected challenges. -

CE 029 792 Lambrecht, Judith J.; and Others Business and Office Education

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 205 780 CE 029 792 AUTHOR Lambrecht, Judith J.; And Others TITLE Business and Office Education: Review and Synthesis of the Research. 3rd Edition. Information Series No. 232. INSTITUTION Ohio State Univ., Columbus. National Center for Research in Vocational Education. SPONS AGENCY National Inst. of Education (ED), Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 81 CONTRACT 400-76-0122 NOTE 181p.; For related documents see ED 011 566 and ED 038 520. AVAILABLE FROM National Center Publications, The National Centerfor Research in Vocational Education, The Ohio State. University, 1960 Kenny Rd., Columbus, OH 43210 ($10.501: 4 EDRS PRICE MF01/PCOB Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Accounting; Bookkeeping: Business Communication:! *Business Education; *Business Skills; Career Education; Data Processing; Doctoral Dissertations; Educational Environment: Educational Objectives;; Educational Philosophy: *Educational Research; Mathematics; *Office Occupations Education; *Office Practice; Shorthand; Social Environment; State of the Art Reviews: Typewriting: Work Environment ABSTRACT This review and synthesis of research in businessand office education is based on doctoral dissertationsand some independent studies completed between 1968 and 1980.Approximately twelve hundred studies are reviewed and representthe following major content areas: philosophy and objectives, educationalenvironment, social and business environment, career education/careers, professional organizations (for teachers, students, and secretaries), bookkeeping and accounting, basic business education,communications, business mathematics, business data processing, shorthandand transcription, typewriting, and word processing. All thecontent areas are broken down into various subareas, such as objectives, curriculum, technology, teaching methods, evaluation, and the like.A comprehensive bibliography of the studies reviewed is included. (CT) *********************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best thatcan be made * * from the original document. -

Guide to Starting and Operating a Small Business!

Business experts www.SBDCMichigan.org helping you 616-331-7480 succeed Guide to In partnership with: Starting and Operating Funded in part through a cooperative agreement with the U.S. Small Business Administration. All opinions, conclusions a Small Business or recommendations expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the SBA. Brought to you by the Michigan Small Business Development Center Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................ 2 1 Personal Assessment .......................................................................................................... 3 2 Steps to Starting a Small Business ...................................................................................... 4 1. Select a Business Idea ................................................................................................. 4 2. Market Research (Feasibility) ....................................................................................... 4 3. Startup Cost/Financial Resources Analysis (Feasibility)............................................... 8 Sources of Financing/Startup Resources.................................................................... 10 Decision Point—Is it Feasible?.................................................................................... 11 4. Write a Business Plan................................................................................................. 12 -

Mckinsey Special Collection Resource Allocation

McKinsey Special Collection Resource allocation Selected articles from the Strategy and Corporate Finance Practice Resource allocation articles How nimble resource allocation can double your company’s value Yuval Atsmon August 2016 read the article Breaking down the barriers to corporate resource allocation Stephen Hall and Conor Kehoe October 2013 read the article Avoiding the quicksand: Ten techniques for more agile corporate resource allocation Michael Birshan, Marja Engel and Oliver Sibony October 2013 read the article Never let a good crisis go to waste Mladen Fruk, Stephen Hall and Devesh Mittal September 2013 read the article How to put your money where your strategy is Stephen Hall, Dan Lovallo and Reinier Musters March 2012 read the article Resource allocation McKinsey Strategy Collection 3 Yuval Atsmon How nimble resource allocation can double your company’s value Strategy August 2016 Companies that actively and regularly reevaluate where resources are allocated create more value and deliver higher returns to shareholders. “Dynamic resource reallocation” is a mouthful, but its meaning is simple: shifting money, talent, and management attention to where they will deliver the most value to your company. It’s one of those things, like daily exercise, that helps us thrive but that gets pushed off our priority list by business that seems more urgent. Most senior executives understand the importance of strategically shifting resources: according to McKinsey research, 83 percent identify it as the top management lever for spurring growth— more important than operational excellence or M&A. Yet a third of companies surveyed reallocate a measly 1 percent of their capital from year to year; the average is 8 percent. -

Choosing Effective Talent Assessments to Strengthen Your Organization

The future of HR is here (and it’s SHRM-certified) Choosing Effective Talent Assessments to Strengthen Your Organization This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information regarding the subject matter covered. Neither the publisher nor the authors are engaged in rendering legal or other professional service. If legal advice or other expert assis- tance is required, the services of a competent, licensed professional should be sought. Any federal and state laws discussed in this report are subject to frequent revision and interpretation by amendments or judicial revisions that may significantly affect employer or employee rights and obligations. Readers are encouraged to seek legal counsel regarding specific policies and practices in their organizations. This book is published by the SHRM Foundation, an affiliate of the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM©). The interpretations, conclusions and recommendations in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the SHRM Foundation. ©2016 SHRM Foundation. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. This publication may not be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in whole or in part, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the SHRM Foundation, 1800 Duke Street, Alexandria, VA 22314. Selection of report topics, treatment of issues, interpretation and other editorial decisions for the Effective Practice Guidelines series are handled by SHRM Foundation staff and the report authors. Report sponsors may review the content prior to publication and provide input along with other reviewers; however, the SHRM Foundation retains final editorial control over the reports. -

Gender, Sex and Gossip in Ambridge: Women in the Archers

GENDER, SEX AND GOSSIP IN AMBRIDGE This page intentionally left blank GENDER, SEX AND GOSSIP IN AMBRIDGE: WOMEN IN THE ARCHERS Edited by DR CARA COURAGE DR NICOLA HEADLAM United Kingdom – North America – Japan – India Malaysia – China Emerald Publishing Limited Howard House, Wagon Lane, Bingley BD16 1WA, UK First edition 2019 Copyright © 2019 Emerald Publishing Limited Reprints and permissions service Contact: [email protected] No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without either the prior written permission of the publisher or a licence permitting restricted copying issued in the UK by The Copyright Licensing Agency and in the USA by The Copyright Clearance Center. Any opinions expressed in the chapters are those of the authors. Whilst Emerald makes every effort to ensure the quality and accuracy of its content, Emerald makes no representation implied or otherwise, as to the chapters’ suitability and application and disclaims any warranties, express or implied, to their use. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN: 978-1-78769-948-9 (Print) ISBN: 978-1-78769-945-8 (Online) ISBN: 978-1-78769-947-2 (Epub) CONTENTS About the Editors vii About the Authors ix Acknowledgements xv Preface Nicola Headlam and Cara Courage 1 Section One – Inside Ambridge 9 1. In Conversation with Alison Hindell Nicola Headlam and Cara Courage 11 2. ‘I’m Not One to Gossip’: Roots, Rumour and Mental Well-being in Ambridge Charlotte Connor, aka Charlotte Martin, and Susan Carter, actor, in BBC Radio 4’s The Archers 21 Section Two – Women’s Talk: Informal Information Networks that Sustain the Village 35 3. -

Inspiring Entrepreneurs: Learning from the Experts

INSPIRING ENTREPRENEURS: LEARNING FROM THE EXPERTS HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON SMALL BUSINESS UNITED STATES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FOURTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION HEARING HELD MAY 11, 2016 Small Business Committee Document Number 114–059 Available via the GPO Website: www.fdsys.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 20–074 WASHINGTON : 2016 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Mar 15 2010 11:42 Nov 22, 2016 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 F:\DOCS\20074.TXT DEBBIE SBREP-219A with DISTILLER Congress.#13 HOUSE COMMITTEE ON SMALL BUSINESS STEVE CHABOT, Ohio, Chairman STEVE KING, Iowa BLAINE LUETKEMEYER, Missouri RICHARD HANNA, New York TIM HUELSKAMP, Kansas CHRIS GIBSON, New York DAVE BRAT, Virginia AUMUA AMATA COLEMAN RADEWAGEN, American Samoa STEVE KNIGHT, California CARLOS CURBELO, Florida CRESENT HARDY, Nevada NYDIA VELA´ ZQUEZ, New York, Ranking Member YVETTE CLARK, New York JUDY CHU, California JANICE HAHN, California DONALD PAYNE, JR., New Jersey GRACE MENG, New York BRENDA LAWRENCE, Michigan ALMA ADAMS, North Carolina SETH MOULTON, Massachusetts MARK TAKAI, Hawaii KEVIN FITZPATRICK, Staff Director JAN OLIVER, Chief Counsel MICHAEL DAY, Minority Staff Director (II) VerDate Mar 15 2010 11:42 Nov 22, 2016 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 F:\DOCS\20074.TXT DEBBIE SBREP-219A with DISTILLER C O N T E N T S OPENING STATEMENTS Page Hon. Steve Chabot ..................................................................................................