Identification of Olive-Backed Pipit, Blyth's Pipit and Pallas's Reed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Host Alarm Calls Attract the Unwanted Attention of the Brood Parasitic

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Host alarm calls attract the unwanted attention of the brood parasitic common cuckoo Attila Marton 1,2*, Attila Fülöp 2,3, Katalin Ozogány1, Csaba Moskát 4,5 & Miklós Bán 1,3,5 It is well known that avian brood parasites lay their eggs in the nests of other bird species, called hosts. It remains less clear, however, just how parasites are able to recognize their hosts and identify the exact location of the appropriate nests to lay their eggs in. While previous studies attributed high importance to visual signals in fnding the hosts’ nests (e.g. nest building activity or the distance and direct sight of the nest from vantage points used by the brood parasites), the role of host acoustic signals during the nest searching stage has been largely neglected. We present experimental evidence that both female and male common cuckoos Cuculus canorus pay attention to their host’s, the great reed warbler’s Acrocephalus arundinaceus alarm calls, relative to the calls of an unparasitized species used as controls. Parallel to this, we found no diference between the visibility of parasitized and unparasitized nests during drone fights, but great reed warblers that alarmed more frequently experienced higher rates of parasitism. We conclude that alarm calls might be advantageous for the hosts when used against enemies or for alerting conspecifcs, but can act in a detrimental manner by providing important nest location cues for eavesdropping brood parasites. Our results suggest that host alarm calls may constitute a suitable trait on which cuckoo nestlings can imprint on to recognize their primary host species later in life. -

The Field Identification of North American Pipits Ben King Illustrated by Peter Hayman and Pieter Prall

The field identification of North American pipits Ben King Illustrated by Peter Hayman and Pieter Prall LTHOUGHTHEWATER PIPIT (Anthus ground in open country. However, the in this paper. inoletta) and the Sprague's Pipit two speciesof tree-pipits use trees for (Antbus spragueit)are fairly easy to rec- singing and refuge and are often in NCEABIRD HAS been recognized asa ogmze using the current popular field wooded areas. pipit, the first thing to checkis the guides, the five species more recently All the pipits discussedin the paper, ground color of the back. Is it brown added to the North American list are except perhaps the Sprague's, move (what shade?), olive, or gray? Then note more difficult to identify and sometimes their tails in a peculiarpumping motion, the black streaks on the back. Are they present a real field challenge. The field down and then up. Some species broad or narrow, sharply or vaguely de- •dentffication of these latter specieshas "pump" their tails more than others. fined, conspicuousor faint? How exten- not yet been adequatelydealt with in the This tail motion is often referred to as sive are they? Then check for pale North American literature. However, "wagging." While the term "wag" does streaks on the back. Are there none, much field work on the identification of include up and down motion as well as two, four, many? What color are they-- pipits has been done in the last few side to side movement, it is better to use whitish, buff, brownish buff? Are they years, especially in Alaska and the the more specificterm "pump" which is conspicuousor faint? Discerningthese Urnted Kingdom. -

EUROPEAN BIRDS of CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, Trends and National Responsibilities

EUROPEAN BIRDS OF CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, trends and national responsibilities COMPILED BY ANNA STANEVA AND IAN BURFIELD WITH SPONSORSHIP FROM CONTENTS Introduction 4 86 ITALY References 9 89 KOSOVO ALBANIA 10 92 LATVIA ANDORRA 14 95 LIECHTENSTEIN ARMENIA 16 97 LITHUANIA AUSTRIA 19 100 LUXEMBOURG AZERBAIJAN 22 102 MACEDONIA BELARUS 26 105 MALTA BELGIUM 29 107 MOLDOVA BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 32 110 MONTENEGRO BULGARIA 35 113 NETHERLANDS CROATIA 39 116 NORWAY CYPRUS 42 119 POLAND CZECH REPUBLIC 45 122 PORTUGAL DENMARK 48 125 ROMANIA ESTONIA 51 128 RUSSIA BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is a partnership of 48 national conservation organisations and a leader in bird conservation. Our unique local to global FAROE ISLANDS DENMARK 54 132 SERBIA approach enables us to deliver high impact and long term conservation for the beneit of nature and people. BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is one of FINLAND 56 135 SLOVAKIA the six regional secretariats that compose BirdLife International. Based in Brus- sels, it supports the European and Central Asian Partnership and is present FRANCE 60 138 SLOVENIA in 47 countries including all EU Member States. With more than 4,100 staf in Europe, two million members and tens of thousands of skilled volunteers, GEORGIA 64 141 SPAIN BirdLife Europe and Central Asia, together with its national partners, owns or manages more than 6,000 nature sites totaling 320,000 hectares. GERMANY 67 145 SWEDEN GIBRALTAR UNITED KINGDOM 71 148 SWITZERLAND GREECE 72 151 TURKEY GREENLAND DENMARK 76 155 UKRAINE HUNGARY 78 159 UNITED KINGDOM ICELAND 81 162 European population sizes and trends STICHTING BIRDLIFE EUROPE GRATEFULLY ACKNOWLEDGES FINANCIAL SUPPORT FROM THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION. -

The Newsletter of the Nest Record Scheme

The newsletter of the Nest Record Scheme Issue 30 MAY 2014 InsIde thIs edItIon 02 news roundup 03 dAvId glue 1947–2014 04 A recorder reFlecTs 05 All-TIMe Top recorders 06 A 13,000 pAge suMMArY 07 Treecreeper boxes 08 nrs AnnuAl Totals 10 nrs MenTorIng 12 moorlAnd MonITorIng 13 runway plovers 14 rockIT scIence 15 nrs latesT resulTs 16 spoT The nesT This season sees the official launch of NRS mentoring. See the article on page 10, and visit www.bto.org/ volunteer-surveys/nrs/taking- part/nrs-mentoring to find your nearest mentor (screenshot below). Top: Bernard Pleasance, John Dries, Tony Davis, Josh Marshall and Richard Castell at the NRS 75th anniversary conference. Left: Veteran recorder David Warden photographing a nest box in 1949. Right: A young nest recorder checking a Song Thrush nest with a mirror in 2011. 75 years of nesting he Hatching and Fledgling year, 80 such volunteers came to the Inquiry was started by the BTO Nunnery for a day of celebrating the T in 1939 to collect information on success of NRS and looking forward facets of basic breeding biology, such to its future. It was thrilling to see as incubation and fledging periods. In like-minded ornithologists from all the first five years, 1,988 nest record over the country meeting up to talk cards were sent in by c.20 participants. about nest recording. We enjoyed Seventy five years on, the Nest Record talks from speakers including David Scheme (NRS) has c.660 active Warden, a recorder since 1948, and recorders and an amazing 1.6 million Josh Marshall, a recorder since 2013! nest records have been collected, an NRS mentor Mark Lawrence gave The NRS mentoring scheme invaluable dataset that has been used a talk to mark the official launch of is generously sponsored by for scientific study far beyond the scope NRS mentoring (see p 10), which of the original inquiry. -

Birds of the Suffolk Coast & Heaths

Birds of The Suffolk Coast & Heaths Holiday Report 22 - 25 May 2017 Led by Ed Hutchings Greenwings Wildlife Holidays Tel: 01473 254658 Web: www.greenwings.co.uk Email: [email protected] ©Greenwings 2017 Introduction The county of Suffolk, like the rest of East Anglia, is a gem for birding. Few have mastered its diversity. From the River Stour in the south, to the River Waveney and the Broads in the north and from The Brecks in the west to the coast in the east, the county provides something for everyone. The Suffolk Coast and Heaths Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty is a stunning landscape, packed full of wildlife within 155 square miles of tranquil and unspoilt landscape, including wildlife-rich estuaries, ancient heaths, windswept shingle beaches and historic towns and villages. Birding in Suffolk is a joy as the landscape of the county is diverse, and so is the range of wildlife that inhabits it. This bird holiday would focus on spring birds in the wonderful habitats found on the Suffolk coast. Group members: Nigel Baelz, Stuart Barnes and Louise Rowlands. There now follows a summary of the activities and highlights from each day, a photo gallery, and a bird species list at the end. Day 1: Monday 22nd May 2017 The guests were met on a hot sunny day at the Westleton Crown by their guide Ed Hutchings for an introduction and a quick bite to eat. The Westleton Crown is a friendly hotel on the Suffolk coast and would be our base for the break. After checking into the hotel after lunch, we headed south to North Warren RSPB near Aldeburgh for the afternoon. -

Early Spring 2021

REPORT OF BIRDLIFE ON ASHDOWN FOREST EARLY SPRING 2021 February 2021 was cold as usual, but the weather was not severe enough to kill off our population of resident DARTFORD WARBLERS. They could be heard calling while sheltering in thick gorse, where they hunted for spiders, their crucial winter diet. Occasionally a fleeting glimpse of a tiny dark-coloured long-tailed bird would confirm the presence of a “furze wren”, the old Sussex name for Dartford Warbler. They rely on heather for nesting and gorse for shelter and most of their food supply. Darford Warbler by Clive Poole Our second avian UK rarity is the WOODLARK and our breeding population arrived back on the Forest in early February from their wintering grounds on the south coast or across the Channel (without needing to comply with lockdown restrictions). This season they have benefited locally from the gorse-management activities of the Conservators, who have removed some large blocks of very tall old straggly gorse, useless for wildlife. This has left areas of bare ground, gorse litter and scattered seeds. Just the job for WOODLARKS who are opportunistic colonisers Woodlark by Clive Poole after fire damage or major ground disturbance. Paradoxically, they both feed and breed on the ground on open heaths (not in woods despite their name) searching the bare and battered ground for seeds and insects. They also favour feeding on short grass grazed by rabbits. An early surprise was to find a male REDSTART on 30th March 2021. He had arrived about a week earlier than usual, making use of a couple of warm days with southerly winds to stage the final leg (across the Channel), of his long journey from his wintering grounds in Gambia or even further south in tropical Africa. -

Unusual Wintering Records of Pipits (Aves: Motacillidae) in Hatay, Eastern Mediterranean Region of Turkey

Turkish Journal of Zoology Turk J Zool (2015) 39: 74-79 http://journals.tubitak.gov.tr/zoology/ © TÜBİTAK Research Article doi:10.3906/zoo-1311-49 Unusual wintering records of pipits (Aves: Motacillidae) in Hatay, Eastern Mediterranean Region of Turkey Ali ATAHAN, Orhan GÜL*, Mehmet ATAHAN, Mehmet GÜL Subaşı Birdwatching Society, Subaşı Beldesi, Hatay, Turkey Received: 25.11.2013 Accepted: 08.05.2014 Published Online: 02.01.2015 Printed: 30.01.2015 Abstract: We studied the unusual wintering records of some rare pipit species during winter in Hatay Province, in the Eastern Mediterranean Region of Turkey. Through intensive field observations performed between 2007 and 2013, 8 pipit species were recorded in the province. Among the observations, 59 were unusual wintering records belonging to 5 pipit species. In this article, we present observations on frequency and seasonality of each pipit species observed in Hatay Province. Meadow, water, and red-throated pipits were already known as winter visitors to the region, but for the first time in this study, we observed buff-bellied, Richard’s, tree, tawny, and Blyth’s pipits in Hatay Province during winter. In light of our observations, we suggest that all 5 species—especially buff-bellied, Richard’s, and tree pipits—might be regular winter visitors to Hatay. Key words: Anthus spp., Aves, Eastern Mediterranean, Hatay, pipits, Turkey, unusual wintering records 1. Introduction Following this unusual observation, we decided to study Pipits are a group of wagtails, which are small, mainly the region in detail to explore the possibility of pipits not terrestrial, and insectivorous birds generally observed only passing through Hatay during migration but also in grasslands and wet meadows, although a few prefer using the region as a regular wintering ground, given shrubby or rocky habitats (Snow and Perrins, 1998; the presence of adequate habitats and suitable weather Alström and Mild, 2003). -

Red-Throated Pipit Anthus Cervinus in Australia

VOL. 17 (1) MARCH 1997 3 AUSTRALIAN BIRD WATCHER 1997, 17, 3-10 Red-throated Pipit Anthus cervinus in Australia by MIKE CARTER, 30 Canadian Bay Road, Mt Eliza, Victoria 3930 Summary A Red-throated Pipit Anthus cervinus was at Broome, Western Australia, from 6 to 9 January 1992. This first record for Australia is described. Identification criteria and difficulties are discussed. This occurrence followed a season in which unprecedented numbers of Red-throated Pipits were recorded along the Pacific coast of North America. It is suggested that the two events are a consequence of a successful breeding season in the Arctic in 1991. Introduction Soon after dawn on 6 January 1992, George Swann, Neil Macumber, Tom Smith and I went to the main sporting oval in Broome, Western Australia. We found a pipit Anthus sp. which was smaller, darker and more boldly marked than the Australian Richard's Pipit A. novaeseelandiae australis. Realising that it was a species not previously recorded in Australia, we studied the bird intently for half an hour before, alarmed by our constant pursuit, it disappeared. We then acquired whatever literature was immediately available on the subject of pipits and attempted to resolve the problem of identification. Swann searched the oval again on 7 January unsuccessfully, but the pipit was relocated next day and also on 9 January. Over these two days, Swann, Macumber and myself each spent between five and ten hours observing the bird, refining our descriptions and obtaining photographs. The data we obtained enabled identification to be confirmed as a Red-throated Pipit A. -

Estimates of Breeding Bird Abundance and Habitat Use in Thetford Forest Park

TITL BTO RESEARCH REPORT 531 Estimates of breeding bird abundance and habitat use in Thetford Forest Park. Greg Conway & Ian Henderson BTO Research Report No. 531 Estimates of Breeding Bird Abundance and Habitat Use in Thetford Forest Park Authors Greg Conway & Ian Henderson Report of work carried out by The British Trust for Ornithology for the Forestry Commission England March 2009 © British Trust for Ornithology British Trust for Ornithology, The Nunnery, Thetford, Norfolk, IP24 2PU Registered Charity No. 216652 CONTENTS Page No. List of Tables ......................................................................................................................................... 3 List of Figures ........................................................................................................................................ 5 List of Appendices ................................................................................................................................. 7 1. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................... 9 2. METHODS ............................................................................................................................. 11 2.1 Survey Sampling Design ........................................................................................................ 11 2.2 Field Methods ......................................................................................................................... 11 2.3 Habitat -

A Reassessment of Meadow Pipit Anthus Pratensis Records from India, and Their Rejection

60 Indian BIRDS VOL. 13 NO. 3 (PUBL. 29 JUNE 2017) point out how immature specimens of Erythropus vespertinus and its Eastern Naoroji, R., 2006. Birds of prey of the Indian Subcontinent. 1st ed. London: representative E. amurensis, are to be distinguished: …”]. Stray Feathers 2 (6): Christopher Helm. Pp. 1–704. 527–529. Radde, G., 1863. Reisen im Süden von Ost-Sibirien in den Jahren 1855–1859. Vol. 2. Hume, A. O., 1879. A rough tentative list of the birds of India. Stray Feathers 8 (1): St. Petersburg. 73–122. Rasmussen, P. C., & Anderton, J. C., 2012. Birds of South Asia: the Ripley guide: Katzner, T. E., Bragin, E. A., Bragin, A. E., McGrady, M., Miller, T. A., & Bildstein, K. L., attributes and status. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C. and Barcelona: Smithsonian 2016. Unusual clockwise loop migration lengthens travel distances and increases Institution and Lynx Edicions. Vol. 2 of 2 vols. Pp. 1–683. potential risks for a central Asian, long distance, trans-equatorial migrant, the Red- Roberts, T. J., 1991. The birds of Pakistan: Regional Studies and non-passeriformes. 1st footed Falcon Falco vespertinus. Bird Study 63: 406–412. ed. Karachi: Oxford University Press. Vol. 1 of 2 vols. Pp. i–xli, 1–598. Kerr, K. C. R., Stoeckle M. Y., Dove C. J., Weigt L. A., Francis C. M., & Hebert P. D. N., Scott, D. A., 2008. Rare birds in Iran in the late 1960s and 1970s. Podoces 3: 1–30. 2007. Comprehensive DNA barcode coverage of North American birds. Molecular Scott, D. A., & Adhami, A., 2006. An updated checklist of the birds of Iran. -

Motacillidae Species Tree

Motacillidae Forest Wagtail, Dendronanthus indicus Dendronanthus Mountain Wagtail, Motacilla clara Cape Wagtail, Motacilla capensis Sao Tome Shorttail, Motacilla bocagii Madagascan Wagtail, Motacilla flaviventris Gray Wagtail, Motacilla cinerea Motacilla Western Yellow Wagtail, Motacilla flava Citrine Wagtail, Motacilla citreola Eastern Yellow Wagtail, Motacilla tschutschensis White-browed Wagtail, Motacilla maderaspatensis Mekong Wagtail, Motacilla samveasnae Japanese Wagtail, Motacilla grandis White Wagtail, Motacilla alba African Pied Wagtail, Motacilla aguimp Upland Pipit, Corydalla sylvana Australian Pipit, Corydalla australis New Zealand Pipit, Corydalla novaeseelandiae Corydalla Tawny Pipit, Corydalla campestris Berthelot’s Pipit, Corydalla berthelotii Richard’s Pipit, Corydalla richardi Paddyfield Pipit, Corydalla rufula Blyth’s Pipit, Corydalla godlewskii Plain-backed Pipit, Corydalla leucophrys Wood Pipit, Corydalla nyassae Long-billed Pipit, Corydalla similis African Pipit, Corydalla cinnamomea Malindi Pipit, Corydalla melindae Buffy Pipit, Corydalla vaalensis Long-legged Pipit, Corydalla pallidiventris Sokoke Pipit, Cinaedium sokokense Short-tailed Pipit, Cinaedium brachyurum Bushveld Pipit, Cinaedium caffrum Cinaedium Mountain Pipit, Cinaedium hoeschi Striped Pipit, Cinaedium lineiventre African Rock Pipit, Cinaedium crenatum Golden Pipit, Tmetothylacus tenellus Tm e t o t h y l a c u s Yellow-breasted Pipit, Hemimacronyx chloris Hemimacronyx Sharpe’s Longclaw, Hemimacronyx sharpei Abyssinian Longclaw, Macronyx flavicollis Fuelleborn’s -

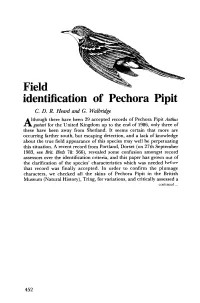

Field Identification of Pechora Pipit C

Field identification of Pechora Pipit C. D. R. Heard and G. Walbridge lthough there have been 29 accepted records of Pechora Pipit Anthus A.gustavi for the United Kingdom up to the end of 1986, only three of these have been away from Shetland. It seems certain that more are occurring farther south, but escaping detection, and a lack of knowledge about the true field appearance of this species may well be perpetuating this situation. A recent record from Portland, Dorset (on 27th September 1983, see Brit. Birds 78: 566), revealed some confusion amongst record assessors over the identification criteria, and this paper has grown out of the clarification of the species' characteristics which was needed before that record was finally accepted. In order to confirm the plumage characters, we checked all the skins of Pechora Pipit in the British Museum (Natural History), Tring, for variations, and critically assessed a continued... 452 Identification of Pechora Pipit 453 sample of 35 for each identification feature. We also took the opportunity to examine skins of Red-throated Pipit A. cervinus (of which we also have extensive Palearctic field experience); this is the principal confusion species, with which we frequently make comparison. We have also assumed a degree of familiarity with Meadow A. pratensis and Tree Pipits A. trivialis: observers should also beware of the effects of moult on the plumage appearance, and apparent structure, of these species. In the past, field guides and handbooks have usually stressed the similarity of Pechora Pipit to Tree Pipit, while ringers' texts have warned against confusion with Red-throated.