FREE SPEECH on CAMPUS AUDIT 2018 Matthew Lesh Research Fellow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Agenda Vol.20

NTEU WOMEN’S JOURNAL Www.NTEU.org.au/women bluestocking week revival of a celebration of educaTed women bluestocking weEk evEnts acrosS the country equity in higher Education baRgaining through a gEnder Lens ouR brilLiant carEers ISSN 1839-6186 volume 20 SeptEMber 2012 NATIONAL TERTIARY EDUCATION UNION MEMBERSHIP FORM I want to join NTEU I am currently a member and wish to update my details The information on this form is needed for aspects of NTEU’s work and will be treated as confidential. WoMen’s action commiTtee (WAc) YOUR PERSONAL DETAILS The NTEU Women’s Action Committee (WAC) develops the Union’s TITLE |SURNAME |GIVEN NAMES work concerning women and their professional and employment rights. HOME ADDRESS The WAC meets twice a year. Its role includes: • Act as a representative of women members at the National level. CITY/SUBURB |STATE |POSTCODE • To identify, develop and respond to matters affecting women. HOME PHONE WORK PHONE INCL AREA CODE | INCL AREA CODE | MOBILE • To advise on recruitment policy and resources directed at women. • To advise on strategies and structures to encourage, support and EMAIL |DATE OF BIRTH | MALE FEMALE facilitate the active participation of women members at all levels of the NTEU. HAVE YOU PREVIOUSLY BEEN AN NTEU MEMBER? YES: AT WHICH INSTITUTION? |ARE YOU AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL/TORRES STRAIT ISLANDER? YES • To recommend action and advise on issues affecting women. YOUR CURRENT EMPLOYMENT DETAILS PLEASE USE MY HOME ADDRESS FOR ALL MAILING WAc DelegAtes 2011-2012 • To inform members on industrial issues and policies that impact on women. INSTITUTION/EMPLOYER |CAMPUS Aca Academic staff representative • To make recommendations and provide advice to the National Exec- MAIL/ FACULTY DEPT/SCHOOL G/P General/Professional staff representative utive, National Council, Division Executives and Division Councils on | |BLDG CODE industrial, social and political issues affecting women. -

![Report: Higher Education and Research Reform Amendment Bill 2014 [Provisions]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0362/report-higher-education-and-research-reform-amendment-bill-2014-provisions-1230362.webp)

Report: Higher Education and Research Reform Amendment Bill 2014 [Provisions]

APPENDIX 1 Submissions Received 1. Prof Jacqueline K 2. Mr Chris Jervis 3. Professor John G 4. Mr Brian Long 5. Dr Rosemary S. O'Donnell 6. Dr Anthony Fricker 7. Mr Victor Ziegler 8. Dr Matthew Fitzpatrick 9. Name Withheld 10. Ms Catherine Chambers 11. Ms Catherine Ogier 12. Dr Martin Young 13. Ms Lisa Ford 14. Isolated Children's Parents' Association of Australia 15. Australian Technology Network of Universities 16. Rev W.J. Uren 17. Australian Association of Social Workers 112 18. Ms Janice Wegner 19. Equity Practitioners in Higher Education Australasia (EPHEA) 20. Mr John Quiggin 21. Mr John McLaren 22. The University of Notre Dame Australia 23. University of South Australia Student Association 24. Mr Damian Buck 25. Australian Catholic University (ACU) 26. Name Withheld 27. Name Withheld 28. Ms Rosamund Winter 29. Holmesglen Institute 30. Queensland Government - Department of Education, Training and Employment 31. Mr Robert Simpson 32. Name Withheld 33. Ms Juna Langford 34. Avondale College of Higher Education 35. Mr Grahame Bowland 36. Mr Ben Bravery 113 37. Dr Geoff Sharrock 38. Name Withheld 39. Name Withheld 40. Mr Matthew Currell 41. Name Withheld 42. Australian Liberal Students' Federation 43. Mr Stephen Lake 44. Mr Trent Bell 45. The University of Western Australia 46. Group of Eight Australia 47. The University of Queensland 48. Council of Private Higher Education (COPHE) 49. PPE Society, La Trobe 50. Dr Nathan Absalom 51. Mrs Robyn Wotherspoon 52. Open Universities Australia 53. CQUniversity Rockhampton 54. Navitas Ltd 55. Mr Peter Gangemi 114 56. Regional Universities Network 57. -

Table of Contents 1

FLINDERS UNIVERSITY STUDENT ASSOCIATION Student Council Agenda Meeting: 14th August 2017 Flinders University Student Council Meeting Agenda of the Meeting held on 14/8/2017 Alere Function Room, Hub level 2 Contents Table of Contents 1. Acknowledgement of Country ........................................................................................................................ 2 2. Apologies .................................................................................................................................................... 2 3. Welcome Guests ................................................................................................................................. 2 4. Previous Minutes ................................................................................................................................. 2 5. Reports ................................................................................................................................................ 2 6. Executive Decisions .................................................................................................................................... 2 7. Matters for Decision .................................................................................................................................. 2 8. Matters for Discussion ................................................................................................................................... 11 9. Matters for Noting .................................................................................................................................. -

Policy Volume Cover2

1 National Union of Students 2012 National Conference Policy Volume Contents Chapter 1: Administration............................................................p3 Chapter 2: Unionism...................................................................p29 Chapter 3: Education..................................................................p45 Chapter 4: Welfare.....................................................................p64 Chapter 5: Women’s...................................................................p81 Chapter 6: Queer......................................................................p104 Chapter 7: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Students.........p133 Chapter 8: International Students............................................p139 Chapter 9: Ethno-cultural Students...........................................p144 Chapter 10: Environment..........................................................p150 Chapter 11: Small and Regional................................................p164 Chapter 12: Miscellaneous........................................................p165 Chapter 13: By Laws Changes....................................................p187 2 CHAPTER 1 - ADMINISTRATION ADMIN 1.1: Increase potency and power of the NUS Preamble: 1. NUS is an important organisation. 2. At the moment there are many challenges facing students and unions in general. 3. This means the student union needs to work towards being stronger and more encouraging of participation than ever. 4. One of the most important challenges facing -

Document 2013

NUS NATIONAL CONFERENCE POLICY DOCUMENT 2013 National Union of Students Inc Authorised Jade Tyrrell, NUS President 2013 NUS POLICY VOLUME 2013 CONTENTS 1. ADMINISTRATION PAGES 1-43 2. UNIONISM PAGES 44-55 3. EDUCATION PAGES 56-88 4. WELFARE PAGES 89-115 5. WOMEN’S PAGES 116-151 6. QUEER PAGES 152-175 7. ABORIGINAL & TORRES STRAIT ISLANDER STUDENTS PAGES 176-186 8. DISABILITIES PAGES 187-201 9. INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS PAGES 202-208 10. ETHNO-CULTURAL STUDENTS PAGES 209-221 11. ENVIRONMENT PAGES 222-251 12. SMALL & REGIONAL PAGES 252-260 13. MISCELLENOUS PAGES 261-269 14. BY-LAWS CHANGES PAGES 270 CHAPTER 1 - ADMINISTRATION ADMIN 1.1: Reassessing what we are, what we do, why we do it and how it can be done Preamble: 1. The National Union of Students (NUS) is the peak representative body for undergraduate students in Australia. 2. NUS works to protect the rights of students across Australia, organises national campaigns on issues affecting students in a range of different areas, and makes sure that the student voice is heard by government, the media, and the public. 3. While in name and ethos the NUS can be seen as a union, the nature of those it represents necessitates that one of the major areas of union power – the ability to strike – is unavailable, in a practical sense if not theoretically. 4. As such it is necessary for the NUS to reconcile its union ethos and morality with the practical application of its work, and recognise that as an organisation its strength lies is the numbers, vibrancy and volume of voice held by students, and the utilisation of these factors in lobbying. -

CISA 2020-2021 Executive Committee Candidates Announcement

CISA 2020-2021 Executive Committee Candidates Announcement Dear Members, Here are the candidates for the 2020-2021 CISA Executive Committee Elections. All candidates must be present at the AGM, 3pm-5pm AEST on the 31st August 2020 for elections. Members will be asked to cast their votes electronically usinG the Electionbuddy platform durinG the AGM. If any nominations are withdrawn from now till the elections, thereby renderinG positions vacant, it will be left to the incominG executive team to call for further nominations. Note: Nominees with a * marked beside their names have been conditionally accepted, pendinG confirmation of additional documents to be provided before 31st of AuGust 2020. For any issues or questions in reGard to the elections, please do not hesitate to contact me at [email protected] Kind ReGards, Annette Kalczynska ReturninG Officer Council of International Students Australia (CISA) PO Box 18096, Melbourne, VIC 3001, Australia www.cisa.edu.au Copyright © 2020 Council of International Students Australia Inc. All rights reserved. National President: Belle Lim My name is Belle Lim, I am applyinG for the position of the National President at CISA. I served on the CISA executive committee as the National Women’s Officer over the past two tenures. I have dedicated myself to be a true, stronG voice for female students in our cohort, and deliverinG initiatives that empower and support our students includinG the Future Female Conference. CISA’s Women’s Office has received tremendous support from students, members and stakeholders. We in turn have Garnered universal recoGnition and respect for our work. I hereby thank all of you who have supported us in any way. -

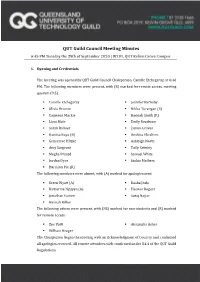

QUT Guild Council Meeting Minutes 6:45 PM Tuesday the 29Th of September 2020 | W201, QUT Kelvin Grove Campus

QUT Guild Council Meeting Minutes 6:45 PM Tuesday the 29th of September 2020 | W201, QUT Kelvin Grove Campus 1. Opening and Credentials The meeting was opened by QUT Guild Council Chairperson, Camille Etchegaray, at 6:46 PM. The following members were present, with (R) marked for remote access, meeting quorum (9.5): ▪ Camille Etchegaray ▪ Jennifer Barnaby ▪ Olivia Brumm ▪ Nikka Turangan (R) ▪ Cameron Mackie ▪ Hannah Smith (R) ▪ Liam Blair ▪ Emily Readman ▪ Sarah Balmer ▪ Jasmin Graves ▪ Ramisa Raya (R) ▪ Anahita Ebrahimi ▪ Genevieve Hitzke ▪ Ashleigh North ▪ Amy Sargeant ▪ Tully Grimley ▪ Megha Prasad ▪ Samuel White ▪ Jordan Dyce ▪ Saskia Mathers ▪ Harrison Pie (R) The following members were absent, with (A) marked for apologies sent: ▪ Seren Wyatt (A) ▪ Rusha Joshi ▪ Katherine Nguyen (A) ▪ Eleanor Rogers ▪ Jonathan Easton ▪ Suraj Najjar ▪ Hamish Killen The following others were present, with (NS) marked for non-students and (R) marked for remote access: ▪ Zoe Vaill ▪ Alexander Asher ▪ William Kroger The Chairperson began the meeting with an Acknowledgment of Country and confirmed all apologies received. All remote attendees with confirmed under R4.4 of the QUT Guild Regulations. 2. Additions/ Deletions to the Agenda The Chairperson called for any additions or deletions to the agenda. Guild President, Olivia Brumm, proposed moving agenda item six (6) to the beginning of the meeting to ensure that quorum is retained for these decisions. No dissent was raised regarding this proposal and agenda item six (6) will be addressed next. 3. Amendments to the Constitution, Regulations or Policy The Chairperson called on Brumm to present the amendments to the QUT Guild Constitution, Regulations, and Election Regulations. -

Principles of the Higher Education and Research Reform Bill 2014, And

APPENDIX 3 Higher Education and Research Reform Amendment Bill 2014 - Submissions Received 1. Prof Jacqueline K 2. Mr Chris Jervis 3. Professor John G 4. Mr Brian Long 5. Dr Rosemary S. O'Donnell 6. Dr Anthony Fricker 7. Mr Victor Ziegler 8. Dr Matthew Fitzpatrick 9. Name Withheld 10. Ms Catherine Chambers 11. Ms Catherine Ogier 12. Dr Martin Young 13. Ms Lisa Ford 14. Isolated Children's Parents' Association of Australia 15. Australian Technology Network of Universities 16. Rev W.J. Uren 54 17. Australian Association of Social Workers 18. Ms Janice Wegner 19. Equity Practitioners in Higher Education Australasia (EPHEA) 20. Mr John Quiggin 21. Mr John McLaren 22. The University of Notre Dame Australia 23. University of South Australia Student Association 24. Mr Damian Buck 25. Australian Catholic University (ACU) 26. Name Withheld 27. Name Withheld 28. Ms Rosamund Winter 29. Holmesglen Institute 30. Queensland Government - Department of Education, Training and Employment 31. Mr Robert Simpson 32. Name Withheld 33. Ms Juna Langford 34. Avondale College of Higher Education 35. Mr Grahame Bowland 55 36. Mr Ben Bravery 37. Dr Geoff Sharrock 38. Name Withheld 39. Name Withheld 40. Mr Matthew Currell 41. Name Withheld 42. Australian Liberal Students' Federation 43. Mr Stephen Lake 44. Mr Trent Bell 45. The University of Western Australia 46. Group of Eight Australia 47. The University of Queensland 48. Council of Private Higher Education (COPHE) 49. PPE Society, La Trobe 50. Dr Nathan Absalom 51. Mrs Robyn Wotherspoon 52. Open Universities Australia 53. CQUniversity Rockhampton 54. Navitas Ltd 56 55. -

2014 REPORT on ANTISEMITISM in AUSTRALIA 1 October 2013 – 30 September 2014

of Australian Jewry ECAJ Public Fund 2014 REPORT on ANTISEMITISM in AUSTRALIA 1 October 2013 – 30 September 2014 This Report is produced to assist understanding of anti-Jewish violence, vandalism, harassment and prejudice in contemporary Australia Researched, written and compiled by JULIE NATHAN REPORT on ANTISEMITISM in AUSTRALIA 2014 1 October 2013 – 30 September 2014 This Report was written, researched and compiled by Julie Nathan, Research Officer, Executive Council of Australian Jewry (ECAJ) This document should not be reproduced or distributed, and the original work not quoted, without the express permission of the author. © Executive Council of Australian Jewry Inc. PO Box 1114, Edgecliff, NSW, 2027 Phone: 02 8353 8500 Email: [email protected] Published by ECAJ, and funded by ECAJ Public Fund, a public fund listed on the Register of Harm Prevention Charities under Subdivision 30-EA of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997. 9 November 2014 1 “The Holocaust did not begin in the gas chambers - it began with words.” - Professor Irwin Cotler, former Canadian Minister of Justice “Through the ages, anti-Semitism has been grounded in the foundational anti-Semitic paradigm. This has five elements: Jews are fundamentally different from non-Jews. Jews are noxious. Jews are willfully malevolent. Jews are powerful. Jews are therefore dangerous. Either implicit or explicitly stated is a sixth element: that Jews must be kept in check, at bay, or somehow eliminated. In every era, specific anti-Semitic elaborations and accusations build upon this foundational paradigm by adapting themselves to the local cultural, social and political conditions of the times.” - Daniel Jonah Goldhagen 2 CONTENTS 1. -

Sharing Initiatives Session Symposium 2017

Creating a National Framework for Student Partnership in University Decision-Making and Governance Sharing Initiatives Session Symposium 2017 Support for this activity has been provided by the Australian Government Department of Education and Training. The views expressed in this activity do not necessarily reflect the views of the Australian Government Department of Education and Training Initiative Page Table Time slot 1. Charles Sturt University- STRIVE – A CSU student 2 1 1.15-1.30pm leadership program pilot 2. Western Sydney University- Respect Now Always 4 2 1.15-1.30pm Campaign 3. Murdoch University- Students as change agents in 5 3 1.15-1.30pm learning and teaching 4. University of South Australia- Student Engagement 6 4 1.15-1.30pm Framework 5. University of NSW- UNSW Heroes 8 5 1.15-1.30pm 6. James Cook University- Student Advisory Committee 10 6 1.15-1.30pm 7. Australian National University- Student Partnership 12 7 1.15-1.30pm Agreement 8. UTS- Staff student consultation committee pilot project 14 1 1.35-1.50pm 9. QUT- Embedding students as partners 16 2 1.35-1.50pm 10. NZUSA & VUWSA- A student representative in every 19 3 1.35-1.50pm classroom 11. Federation University- FedUni student–university 21 4 1.35-1.50pm partnership for the development of improved student engagement in decision making 12. University of New England - Building a UNE model for 22 5 1.35-1.50pm maximising student participation in governance 13. Flinders University- Stop Collaborate and Listen: Topic 24 6 1.35-1.50pm Rep Pilot at Flinders University 14. -

NUS Policy Book 2018__2 .Pdf

ADMIN 2.12 - Affiliations Strategy 2019 ............................................ 29 CONTENTS ADMIN 2.13 - Conference Registration and Information Guidelines .. 31 ADMIN 2.14 - Developing Strategic Relationships ............................. 32 ADMIN 2.15 - Don’t Work with the Liberals in Elections .................. 33 ADMIN 2.16 - Against KPIs ................................................................ 34 ADMIN 2.17: Smokers are Jokers: Ban Smoking at NUS Conferences Constitution, Regulation and By-Law Policy ............................................. 9 ............................................................................................................... 35 CRBL 1.1 - Alterations to B87 of the NUS Constitution ..................... 10 ADMIN 2.18 - Formatting the NUS constitution, regulations and by- CRBL 1.2 - Removal of B48.2(iii) of the NUS By-Laws ..................... 10 laws ....................................................................................................... 36 CRBL 1.3 - *Upside down smiley face x20* ....................................... 11 ADMIN 2.19 - Feedback To Campaigns .............................................. 36 CRBL 1.4 - Term Limits ....................................................................... 11 ADMIN 2.20 - We have a website? ...................................................... 37 CRBL 1.5 - Further Education .............................................................. 11 ADMIN 2.21 - Smoking > Vaping ...................................................... -

Sharing Initiatives Session Symposium 2017

Creating a National Framework for Student Partnership in University Decision-Making and Governance Sharing Initiatives Session Symposium 2017 Support for this activity has been provided by the Australian Government Department of Education and Training. The views expressed in this activity do not necessarily reflect the views of the Australian Government Department of Education and Training Initiative Page Table Time slot 1. Charles Sturt University- STRIVE – A CSU student 2 1 1.15-1.30pm leadership program pilot 2. Western Sydney University- Respect Now Always 4 2 1.15-1.30pm Campaign 3. Murdoch University- Students as change agents in 5 3 1.15-1.30pm learning and teaching 4. University of South Australia- Student Engagement 6 4 1.15-1.30pm Framework 5. University of NSW- UNSW Heroes 8 5 1.15-1.30pm 6. James Cook University- Student Advisory Committee 10 6 1.15-1.30pm 7. Australian National University- Student Partnership 12 7 1.15-1.30pm Agreement 8. UTS- Staff student consultation committee pilot project 14 1 1.35-1.50pm 9. QUT- Embedding students as partners 16 2 1.35-1.50pm 10. NZUSA & VUWSA- A student representative in every 19 3 1.35-1.50pm classroom 11. Federation University- FedUni student–university 21 4 1.35-1.50pm partnership for the development of improved student engagement in decision making 12. University of New England - Building a UNE model for 22 5 1.35-1.50pm maximising student participation in governance 13. Flinders University- Stop Collaborate and Listen: Topic 24 6 1.35-1.50pm Rep Pilot at Flinders University 14.