Effects of Catastrophic Events on Transportation System Management and Operations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of 1 PROCUREMENT DEPARTMENT 4 WORLD TRADE CENTER

PROCUREMENT DEPARTMENT 4 WORLD TRADE CENTER 150 GREENWICH STREET, 21ST FL. NEW YORK, NY 10007 12/11/2018 ADDENDUM # 1 To prospective Respondent(s) on RFP#55599 - Request for Proposals to Provide, Install, and Maintain an Under-Vehicle Surveillance System at the World Trade Center HUB The following change/modification is hereby made in the solicitation documents: 1) All references to “Attachment J – Pilot Agreement” or “Exhibit J – Pilot Agreement” shall be amended and replaced by the appropriate reference, “Attachment D – Pilot Agreement”. 2) The Pilot Agreement (Attachment D) which was erroneously omitted from the Solicitation document, is now made available as part of this Addendum. The due date for this RFP remains unchanged. This communication should be initialed by you and annexed to your response upon submission. In case any Respondent fails to conform to these instructions, its Proposal will nevertheless be construed as though this communication had been so physically annexed and initialed. THE PORT AUTHORITY OF NY & NJ Luke Bassis, Deputy Director PROCUREMENT DEPARTMENT FIRM NAME: ________________________________________________ INITIALED: ____________________________________________________________ DATE: _________________________________________________________________ QUESTIONS CONCERNING THIS ADDENDUM MAY BE ADDRESSED TO Donald Thompson, WHO CAN BE REACHED AT (212) 435 - 4659 or at [email protected]. Page 1 of 1 December 11, 2018 Port Authority Pilot Agreement – (Attachment D) UVSS RFP Pursuant to RFP #55599 the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (the “Port Authority” or “Authority”) has selected the Under Vehicle Security Screening (UVSS) solution (“Product”) proposed by your firm (“Proposer”) for an on-site pilot demonstration (the “Test”) at the Port Authority Vehicle Security Center. -

Breaking New Ground 2017 Annual Report

BREAKING NEW GROUND 2017 Annual Report Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for the Year Ended December 31, 2017. Our Mission Meet the critical transportation infrastructure needs of the bi-state region’s people, businesses, and visitors by providing the highest-quality and most efficient transportation and port commerce facilities and services to move people and goods within the region, provide access to the nation and the world, and promote the region’s economic development. Our mission is simple: to keep the region moving. 2 THE PORT AUTHORITY OF NY & NJ TABLE OF CONTENTS I ntroductory Section 2 Origins of The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey 3 Letter of Transmittal to the Governors 4 Board of Commissioners 5 Leadership of the Port Authority Our Core Business Imperatives 9 Investment 10 Safety and Security 11 Integrity 12 Diversity and Inclusion 13 Sustainability and Resiliency Major Milestones By Business Line 15 2017 at a Glance 16 Aviation 20 Tunnels, Bridges & Terminals 24 Port of New York and New Jersey 28 Port Authority Trans-Hudson Corporation (PATH) 30 World Trade Center Financial Section 32 Chief Financial Officer’s Letter of Transmittal to the Board of Commissioners 35 Index to Financial Section Corporate Information Section 126 Selected Statistical, Demographic, and Economic Data 127 Top 20 Salaried Staff as of December 31, 2017 The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for the Year Ended December 31, 2017 Prepared by the Marketing and Comptroller’s departments of The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey 4 World Trade Center, 150 Greenwich Street, 23rd Floor, New York, NY 10007 www.panynj.gov BREAKING NEW GrounD 1 The Port District includes the cities of New York and Yonkers in New York State; the cities of Newark, Jersey City, Bayonne, Hoboken, and Elizabeth in the State of New Jersey; and more than 200 other municipalities, including all or part of 17 counties, in the two states. -

TM 3.1 Inventory of Affected Businesses

N E W Y O R K M E T R O P O L I T A N T R A N S P O R T A T I O N C O U N C I L D E M O G R A P H I C A N D S O C I O E C O N O M I C F O R E C A S T I N G POST SEPTEMBER 11TH IMPACTS T E C H N I C A L M E M O R A N D U M NO. 3.1 INVENTORY OF AFFECTED BUSINESSES: THEIR CHARACTERISTICS AND AFTERMATH This study is funded by a matching grant from the Federal Highway Administration, under NYSDOT PIN PT 1949911. PRIME CONSULTANT: URBANOMICS 115 5TH AVENUE 3RD FLOOR NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10003 The preparation of this report was financed in part through funds from the Federal Highway Administration and FTA. This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The contents of this report reflect the views of the author who is responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the data presented herein. The contents do no necessarily reflect the official views or policies of the Federal Highway Administration, FTA, nor of the New York Metropolitan Transportation Council. This report does not constitute a standard, specification or regulation. T E C H N I C A L M E M O R A N D U M NO. -

GETTING on TRACK How a Little-Noticed Freight Line Plans to Help Free the City from Its Traf C Nightmare PAGE 18

CRAINSNEW YORK BUSINESS A blue Albany could have businesses seeing red P. 8 | Gearing up for e-bikes P. 10 | The List: Top-paid hospital execs P. 16 NEW YORK BUSINESS® APRIL 9 - 15, 2018 | PRICE $3.00 GETTING ON TRACK How a little-noticed freight line plans to help free the city from its traf c nightmare PAGE 18 VOL. XXXIV, NO. 15 WWW.CRAINSNEWYORK.COM CUSTOM CONTENT *2018’s Notable Women in Finance P. 21 NEWSPAPER P001_CN_20180409.indd 1 4/6/18 7:50 PM APRIL 9 - 15, 2018 CRAINSNEW YORK BUSINESS ON THE COVER PHOTO: BUCK ENNIS FROM THE NEWSROOM | BRENDAN O’CONNOR | MANAGING EDITOR Healthy conversations ONE OF THE PRINCIPAL PLEASURES of working in the Crain’s news- room is when some of the city’s top business and political leaders stop by to meet our editorial board and discuss the issues that matter to them most. Whether with aspiring politicos or trade group reps, real estate developers or special-interest lobbyists, the conversations— parts of which are on the record, others o—are consistently lively, occasionally contentious but always edifying. Last week brought Northwell Health CEO Michael Dowling, who has been I’m a big believer at the helm of the state’s largest health in creating a and hospital system—and, with 66,000 “ workers on the payroll, its largest pri- culture of vate employer—since 2002. e discus- continuous P. sion touched on a wide range of topics, 18 learning from research advances in bioelectron- ic medicine to the invaluable insights IN THIS ISSUE that Dowling gleans from talking to hospital valet parkers. -

1 World Trade Center Llc, Et Al

1 WORLD TRADE CENTER LLC, ET AL. - DETERMINATION - 12/03/09 In the Matter of 1 WORLD TRADE CENTER LLC, ET AL. TAT(H)07-34 (CR), ET AL. - DETERMINATION NEW YORK CITY TAX APPEALS TRIBUNAL ADMINISTRATIVE LAW JUDGE DIVISION COMMERCIAL RENT TAX – THE LESSEES' PAYMENTS TO THE PORT AUTHORITY AFTER SEPTEMBER 11, 2001 DID NOT CONSTITUTE BASE RENT PAID FOR TAXABLE PREMISES BECAUSE THE LESSEES NO LONGER HAD THE RIGHT TO OCCUPY SPECIFIC SPACE AFTER THE GOVERNMENT TAKEOVER OF THE WORLD TRADE CENTER SITE ON SEPTEMBER 11, 2001. THUS, THE COMMERCIAL RENT TAX DOES NOT APPLY TO THOSE PAYMENTS. DECEMBER 3, 2009 NEW YORK CITY TAX APPEALS TRIBUNAL ADMINISTRATIVE LAW JUDGE DIVISION : In the Matter of the Petition : DETERMINATION : of : : TAT(H)07-34(CR), et al. 1 World Trade Center LLC, et al. : : Schwartz, A.L.J.: Petitioners, 1 World Trade Center LLC, 2 World Trade Center LLC, 4 World Trade Center LLC and 5 World Trade Center LLC (now known as 3 World Trade Center LLC) (“Petitioners” or the “Silverstein Lessees”) filed Petitions for Hearing with the New York City (“City”) Tax Appeals Tribunal (“Tribunal”) seeking redeterminations of deficiencies of City Commercial Rent Tax (“CRT”) under Chapter 7 of Title 11 of the City Administrative Code (“Code”) for the five tax years beginning June 1, 2001 and ending May 31, 2006 (“Tax Years”). A hearing was held and various documents were admitted into evidence. Petitioners were represented by Elliot Pisem, Esq. and Joseph Lipari, Esq. of Roberts & Holland LLP. The Commissioner of Finance (“Respondent” or “Commissioner”) was represented by Frances J. -

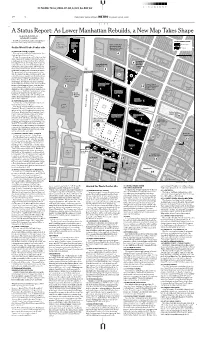

As Lower Manhattan Rebuilds, a New Map Takes Shape

ID NAME: Nxxx,2004-07-04,A,024,Bs-BW,E2 3 7 15 25 50 75 85 93 97 24 Ø N THE NEW YORK TIMES METRO SUNDAY, JULY 4, 2004 CITY A Status Report: As Lower Manhattan Rebuilds, a New Map Takes Shape By DAVID W. DUNLAP and GLENN COLLINS Below are projects in and around ground DEVELOPMENT PLAN zero and where they stood as of Friday. Embassy Goldman Suites Hotel/ Sachs Bank of New York BUILDINGS UA Battery Park Building Technology and On the World Trade Center site City theater site 125 Operations Center PARKS GREENWICH ST. 75 Park Place Barclay St. 101 Barclay St. (A) FREEDOM TOWER / TOWER 1 2 MURRAY ST. Former site of 6 World Trade Center, the 6 United States Custom House 0Feet 200 Today, the cornerstone will be laid for this WEST BROADWAY skyscraper, with about 60,000 square feet of retail space at its base, followed by 2.6 mil- Fiterman Hall, lion square feet of office space on 70 stories, 9 Borough of topped by three stories including an obser- Verizon Building Manhattan PARK PL. vation deck and restaurants. Above the en- 4 World 140 West St. Community College closed portion will be an open-air structure Financial 3 5 with wind turbines and television antennas. Center 7 World The governor’s office is a prospective ten- VESEY ST. BRIDGE Trade Center 100 Church St. ant. Occupancy is expected in late 2008. The WASHINGTON ST. 7 cost of the tower, apart from the infrastruc- 3 World 8 BARCLAY ST. ture below, is estimated at $1 billion to $1.3 Financial Center billion. -

Manhattan Office Market

Manhattan Offi ce Market 1 ST QUARTER 2016 REPORT A NEWS RECAP AND MARKET SNAPSHOT Pictured: 915 Broadway Looking Ahead Finance Department’s Tentative Assessment Roll Takes High Retail Rents into Account Consumers are not the only ones attracted by the luxury offerings along the city’s prime 5th Avenue retail corridor between 48th and 59th Streets where activity has raised retail rents. The city’s Department of Finance is getting in on the action, prompting the agency to increase tax assessments on some of the high-profi le properties. A tentative tax roll released last month for the 2016-2017 tax year brings the total market value of New York City’s real estate to over $1 trillion — reportedly for the fi rst time. The overall taxable assessed values for the city would increase 8.10%. Brooklyn’s assessed values accounted for the sharpest rise of 9.83% from FY 2015/2016, followed by Manhattan’s 8.47% increase. Although some properties along the 5th Avenue corridor had a reduction in valuations the properties were primarily offi ce, not retail according to a reported analysis of the tentative tax roll details. Building owners have the opportunity to appeal the increase; but an unexpected rise in market value — and hence real estate taxes, will negatively impact the building’s bottom line and value. Typically tenants incur the burden of most of the tax increases from the time the lease is signed, and the landlord pays the taxes that existed before the signing; but in some cases the tenant increase in capped, leaving the burden of the additional expense on the landlord. -

The Impact of Sports Events on Urban Development in Post-Mao China: a Case Study of Guangzhou

ABSTRACT THE IMPACT OF SPORTS EVENTS ON URBAN DEVELOPMENT IN POST-MAO CHINA: A CASE STUDY OF GUANGZHOU By Hong Chen The study on the relationship between sports and cities has proliferated among academics. However, research is mostly focused on developed countries such as the United States and Europe. What kind of impacts do sports events have on Chinese cities? Do sports-events influence post-Mao China differently than developed countries? Assessing the impacts that sporting mega-events have on Guangzhou, which will host the 16th Asian Game in 2010, this research reveals that China’s governments are the key actor in the process of bidding for and hosting mega-sports events. Cities in China have used this strategy to stimulate new district development instead of urban redevelopment. The city governments in China are pursuing sporting mega-events for infrastructure improvement rather than economic issues. The construction of new stadiums and infrastructure, environmental improvement, city image improvement and district development are positive outcomes; however, there is a lack of economic assessment. There is a need for the city to cooperate with the private sector, adopt public participation and to develop a cost-effective use of sports facilities after the sporting mega-events are over. THE IMPACT OF SPORTS EVENTS ON URBAN DEVELOPMENT IN POST-MAO CHINA: A CASE STUDY OF GUANGZHOU A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts Department of Geography by Hong Chen Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2006 Advisor: Stanley W. Toops Reader: James M. -

2014 Annual Report a Clear Path Forward

Front Cover 2014 ANNUAL REPORT A clear path forward Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for the Year Ended December 31, 2014 remove this page for final printng - different paper stock Mission Mission Meet the critical transportation infrastructure needs of the bistate region’s people, businesses, and visitors by providing the highest-quality and most-efficient transportation and port commerce facilities and services to move people and goods within the region, provide access to the nation and the world, and promote the region’s economic development. 2 PORT AUTHORITY OF NEW YORK & NEW JERSEY Table of Contents INTRODUCTORY SECTION INTRODUCTORY SECTION 2 Select Facilities 3 Chairman’s Letter of Transmittal to the Governors 4 Board of Commissioners 4 Leadership of the Port Authority 5 Governance Initiatives 6 Officers and Executive Management 7 Letter from the Executive Director 9 The Port District 11 A Clear Path Forward FINAnciAL sectionI 46 Chief Financial Officer’s Letter of Transmittal to the Board of CommissionersTORY SECTIO 49 Index to Financial Section corPorAte inforMAtionINTRODUCTORY SECTION 115 Selected Statistical, Demographic, and Economic Data 116 Top 20 Salaried Staff as of December 31, 2014 The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for the Year Ended December 31, 2014 Prepared by the Marketing and Comptroller’s departments of The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey 4 World Trade Center, 150 Greenwich Street, 23rd Floor, New York, NY 10007 www.panynj.gov A CLEAR PATH FORWARD 1 Select Facilities Select Facilities The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey’s facilities include America’s busiest airport system, the Port of New York and New Jersey, the PATH rail transit system, six tunnels and bridges connecting New York and New Jersey, and the Port Authority Bus Terminal in Manhattan. -

Major Projects Update

EMPLOYMENT & OFFICE RETAIL TOURISM & HOSPITALITY RESIDENTIAL MAJOR PROJECTS UPDATE ALLIANCE FOR DOWNTOWN NEW YORK LOWER MANHATTAN REAL ESTATE MARKET OVERVIEW Q2 2016 COMMERCIAL OFFICE MARKET Lower Manhattan’s commercial market sent mixed signals through the second quarter of 2016, echoing trends also seen in other Private Sector Employment submarkets. Office leasing was on par with activity last year but still below the historical average, and news of new major tenant Total Private relocations remained quiet. Despite this, there were clear areas 232,200 Sector Workers of strength. The vacancy rate is currently below 10 percent, and key Lower Manhattan companies committed to stay or expand Additional Workers in new locations south of Chambers Street. The arrival of new 5,100 Year Over Year commercial tenants and the opening of hotels and retail has pushed Lower Manhattan’s private sector employment to grow, workers or 2% growth year over year. The employment expansion reaching a new post-2001 peak of more than 232,000 employees cuts across all the key sectors that have been fueling Lower 1 as of the end of 2015. Manhattan’s economy and leasing activity. EMPLOYMENT The hotel, retail and restaurant sectors added the largest share of employees to Lower Manhattan over the course of 2015. These Private sector employment climbed to nearly 232,200 employees as industries grew by more than 2,000 employees or 10%. More than of the end of 2015, marking the sixth consecutive year of growth and 58 stores and restaurants were added to the retail market, including the highest point since Lower Manhattan had 236,700 private sector Brookfield Places’ offerings as well as three hotels with over 433 rooms.2 employees at the end of 2001. -

1 WORLD TRADE CENTER LLC, Et Al

New York City Tax Appeals Tribunal -----------------------------------------------------------x : In the Matter of : : DECISION 1 WORLD TRADE CENTER LLC, et al. : : TAT (E) 07-34(CR), et al. Petitioners. : : : -----------------------------------------------------------x The Commissioner of Finance of the City of New York (“Respondent”) filed an Exception to a Determination of an Administrative Law Judge (the “ALJ”) dated December 3, 2009 (the “ALJ Determination”). The ALJ Determination cancelled Notices of Determination issued by the New York City Department of Finance (the “Department”) that asserted New York City Commercial Rent Tax (“CRT”) deficiencies against 1 World Trade Center LLC, 2 World Trade Center LLC, 4 World Trade Center LLC and 5 World Trade Center LLC, now known as 3 World Trade Center LLC, (collectively “Petitioners” or the “Silverstein Lessees”) for the 12-month CRT tax years beginning June 1, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004 and 2005 (the “Tax Years”). Petitioners filed a Cross-Exception to the ALJ Determination (“Petitioners’ Cross-Exception”). Petitioners appeared by Elliot Pisem, Esq. and Joseph Lipari, Esq. of Roberts & Holland LLP. Respondent appeared by Frances J. Henn, Esq., Senior Corporation Counsel, and Joshua M. Wolf, Esq., Assistant Corporation Counsel, New York City Law Department. The Parties filed briefs and oral argument was held before this Tribunal. Each of the Silverstein Lessees entered into an Agreement of Lease with the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (the “Port Authority”) dated as of July 16, 2001, having a term of 99 years (individually a “Lease” and collectively the “Leases”).1 Each Lease related to one of four buildings, respectively known as “One World Trade Center,” “Two World Trade Center,” “Four World Trade Center” and “Five World Trade Center” (the “Buildings”). -

120 Greenwich Retail Brochure Final

50,815* people walk by this corner every day... RETAIL LOCATION FOR LEASE For More Information: Charles G. Cecil *Pedestrian count verified by Granville International Audience Research and Analysis Tel: (212) 366-6536 New York, NY Fax: (646) 349-5078 SEE 2014 REPORT INSIDE 120 GREENWICH - RETAIL LOCATION FOR LEASE 98 GREENWICH 99 Washington St. Marriott Hotel (180 Hotel Rooms) Holiday Inn (497 Rooms) (400 Rooms) W Hotel (220 Hotel Rooms) 111 Washington St. (223 Condominiums) 52-Story Apartment Building 90 West Street 120 GREENWICH (RETAIL) (410 New Apartments) American Stock Exchange Project 150 GREENWICH Club Quarters Hotel 4 World Trade Center (289 Rooms) (2.5 Million Sq Ft) 123 GREENWICH Fisher Brothers (New Residential Tower) 133 GREENWICH (317 Hotel Rooms) 175 GREENWICH 3 World Trade Center (2.8 Million Sq Ft) 50,815 PEOPLE WALK BY 120 GREENWICH DAILY. 7,000 of these pedestrians enter the WTC memorial every day. Not included in the above count, 26,500 new office workers will arrive CALATRAVA soon at 150 Greenwich and 175 Greenwich just north of 120 Greenwich. Transportation Hub For information, contact Granville International; (917) 848-4904; [email protected] 18,547,600 PEOPLE WALK BY 120 GREENWICH ANNUALLY AND that’S INCREASING 4,683 SQUARE FEET WITH A SIDEWALK LEVEL ENTRANCE, IT HAS 209 FEET OF FRONTAGE ON THREE STREETS AND 640 SQUARE FEET (160 LINEAR FEET) OF WRAP-AROUND SIGNAGE ON THREE STREETS. 18,547,600 FOOT TRAFFIC PER YEAR ONE BLOCK TO THE NORTH ON THE PROMENADE, 12,500 NEW OFFICE WORKERS will inhabit the now open 2.5 Million square foot office tower, 150 Greenwich – 4 World Trade Center.