African Wild Dogs from South-Eastern Kenya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baseline Review and Ecosystem Services Assessment of the Tana River Basin, Kenya

IWMI Working Paper Baseline Review and Ecosystem Services Assessment of the Tana 165 River Basin, Kenya Tracy Baker, Jeremiah Kiptala, Lydia Olaka, Naomi Oates, Asghar Hussain and Matthew McCartney Working Papers The publications in this series record the work and thinking of IWMI researchers, and knowledge that the Institute’s scientific management feels is worthy of documenting. This series will ensure that scientific data and other information gathered or prepared as a part of the research work of the Institute are recorded and referenced. Working Papers could include project reports, case studies, conference or workshop proceedings, discussion papers or reports on progress of research, country-specific research reports, monographs, etc. Working Papers may be copublished, by IWMI and partner organizations. Although most of the reports are published by IWMI staff and their collaborators, we welcome contributions from others. Each report is reviewed internally by IWMI staff. The reports are published and distributed both in hard copy and electronically (www.iwmi.org) and where possible all data and analyses will be available as separate downloadable files. Reports may be copied freely and cited with due acknowledgment. About IWMI IWMI’s mission is to provide evidence-based solutions to sustainably manage water and land resources for food security, people’s livelihoods and the environment. IWMI works in partnership with governments, civil society and the private sector to develop scalable agricultural water management solutions that have -

Forest Cover and Change for the Eastern Arc Mountains and Coastal Forests of Tanzania and Kenya Circa 2000 to Circa 2010

Forest cover and change for the Eastern Arc Mountains and Coastal Forests of Tanzania and Kenya circa 2000 to circa 2010 Final report Karyn Tabor, Japhet J. Kashaigili, Boniface Mbilinyi, and Timothy M. Wright Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 2 1.1 Biodiversity Values of the Eastern Arc Mountains and Coastal Forests ....................................... 2 1.2 The threats to the forests ............................................................................................................. 5 1.3 Trends in deforestation ................................................................................................................. 6 1.4 The importance of monitoring ...................................................................................................... 8 Methods ........................................................................................................................................................ 8 2.1 study area ............................................................................................................................................ 8 2.1 Mapping methodology ........................................................................................................................ 8 2.3 Habitat change statistics ..................................................................................................................... 9 2.4 Map validation -

Beatragus Hunteri) in Arawale National Reserve, Northeastern, Kenya

The population size, abundance and distribution of the Critically Endangered Hirola Antelope (Beatragus hunteri) in Arawale National Reserve, Northeastern, Kenya. Francis Kamau Muthoni Terra Nuova, Transboundary Environmental Project, P.O. Box 74916, Nairobi, Kenya Email: [email protected] 1.0. Abstract. This paper outlines the spatial distribution, population size, habitat preferences and factors causing the decline of Hirola antelope in Arawale National Reserve (ANR) in Garissa and Ijara districts, north eastern Kenya. The reserve covers an area of 540Km2. The objectives of the study were to gather baseline information on hirola distribution, population size habitat preferences and human activities impacting on its existence. A sampling method using line transect count was used to collect data used to estimate the distribution of biological populations (Norton-Griffiths, 1978). Community scouts collected data using Global Positioning Systems (GPS) and recorded on standard datasheets for 12 months. Transect walks were done from 6.00Am to 10.00Am every 5th day of the month. The data was entered into a geo-database and analysed using Arcmap, Ms Excel and Access. The results indicate that the population of hirola in Arawale National Reserve were 69 individuals comprising only 6% of the total population in the natural geographic range of hirola estimated to be 1,167 individuals. It also revealed that hirola prefer open bushes and grasslands. The decline of the Hirola on its natural range is due to a combination of factors, including, habitat loss and degradation, competition with livestock, poaching and drought. Key words: Hirola Antelope Beatragus hunteri, GIS, Endangered Species 2.0. Introduction. The Hirola antelope (Beatragus hunteri) is a “Critically Endangered” species endemic to a small area in Southeast Kenya and Southwest Somalia. -

Evaluating Support for Rangeland‐Restoration Practices by Rural Somalis

Animal Conservation. Print ISSN 1367-9430 Evaluating support for rangeland-restoration practices by rural Somalis: an unlikely win-win for local livelihoods and hirola antelope? A. H. Ali1,2,3 ,R.Amin4, J. S. Evans1,5, M. Fischer6, A. T. Ford7, A. Kibara3 & J. R. Goheen1 1 Department of Zoology and Physiology, University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY, USA 2 National Museums of Kenya, Nairobi, Kenya 3 Hirola Conservation Programme, Garissa, Kenya 4 Conservation Programmes, Zoological Society of London, London, UK 5 The Nature Conservancy, Fort Collins, CO, USA 6 Center for Conservation in the Horn of Africa, St. Louis Zoo, St. Louis, MO, USA 7 Department of Integrative Biology, University of Guelph, Guelph, ON, Canada Keywords Abstract Beatragus hunteri; elephant; endangered species; habitat degradation; rangeland; In developing countries, governments often lack the authority and resources to restoration; tree encroachment; antelope. implement conservation outside of protected areas. In such situations, the integra- tion of conservation with local livelihoods is crucial to species recovery and rein- Correspondence troduction efforts. The hirola Beatragus hunteri is the world’s most endangered Abdullahi H. Ali, Department of Zoology and antelope, with a population of <500 individuals that is restricted to <5% of its his- Physiology, University of Wyoming, Laramie, torical geographic range on the Kenya–Somali border. Long-term hirola declines WY, USA. have been attributed to a combination of disease and rangeland degradation. Tree Email: [email protected] encroachment—driven by some combination of extirpation of elephants, overgraz- ing by livestock, and perhaps fire suppression—is at least partly responsible for Editor: Darren Evans habitat loss and the decline of contemporary populations. -

Isolation of Tick and Mosquito-Borne Arboviruses from Ticks Sampled from Livestock and Wild Animal Hosts in Ijara District, Kenya

VECTOR-BORNE AND ZOONOTIC DISEASES Volume 13, Number X, 2013 ORIGINAL ARTICLE ª Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. DOI: 10.1089/vbz.2012.1190 Isolation of Tick and Mosquito-Borne Arboviruses from Ticks Sampled from Livestock and Wild Animal Hosts in Ijara District, Kenya Olivia Wesula Lwande,1,2 Joel Lutomiah,3 Vincent Obanda,4 Francis Gakuya,4 James Mutisya,3 Francis Mulwa,1 George Michuki,5 Edith Chepkorir,1 Anne Fischer,6 Marietjie Venter,2 and Rosemary Sang1,3 Abstract Tick-borne viruses infect humans through the bite of infected ticks during opportunistic feeding or through crushing of ticks by hand and, in some instances, through contact with infected viremic animals. The Ijara District, an arid to semiarid region in northern Kenya, is home to a pastoralist community for whom livestock keeping is a way of life. Part of the Ijara District lies within the boundaries of a Kenya Wildlife Service–protected conservation area. Arbovirus activity among mosquitoes, animals, and humans is reported in the region, mainly because prevailing conditions necessitate that people continuously move their animals in search of pasture, bringing them in contact with ongoing arbovirus transmission cycles. To identify the tick-borne viruses circulating among these communities, we analyzed ticks sampled from diverse animal hosts. A total of 10,488 ticks were sampled from both wildlife and livestock hosts and processed in 1520 pools of up to eight ticks per pool. The sampled ticks were classified to species, processed for virus screening by cell culture using Vero cells and RT-PCR (in the case of Hyalomma species), followed by amplicon sequencing. -

North Eastern Province (PRE) Trunk Roads ABC Road Description

NORTH EASTERN PROVINCE North Eastern Province (PRE) Trunk Roads ABC Road Description Budget Box culvert on Rhamu-Mandera B9 6,000,000 A3 (DB Tana River) Garissa - Dadaab - (NB Somali) Nr Liboi 14,018,446 C81 (A3) Modika - (B9) Modogashe 24,187,599 B9 (DB Wajir East) Kutulo - Elwak - Rhamu - (NB Somali) Mandera 11,682,038 Regional Manager Operations of office 4,058,989 Regional Manager RM of Class ABC unpaved structures 725,628 B9 (DB Lagdera) Habaswein - Wajir - (DB Mandera East) Kutulo 31,056,036 C80 (DB Moyale) Korondile - (B9) Wajir 29,803,573 A3 (DB Mwingi) Kalanga Corner- (DB Garissa) Tana River 16,915,640 A3 (DB Mwingi) Kalanga Corner- (DB Garissa) Tana River 90,296,144 North Eastern (PRE) total 228,744,093 GARISSA DISTRICT Trunk Roads ABC Road Description Budget (DB Garissa) Tana River- Garissa Town 21,000,000 Sub Total 21,000,000 District Roads DRE Garissa District E861 WARABLE-A3-D586 2,250,000.00 R0000 Admin/Gen.exp 302,400.00 URP26 D586(OHIO)-BLOCK 4,995,000.00 Total . forDRE Garissa District 7,547,400.00 Constituency Roads Garissa DRC HQ R0000 Administration/General Exp. 1,530,000.00 Total for Garissa DRC HQ 1,530,000.00 Dujis Const D586 JC81-DB Lagdera 1,776,000.00 E857 SAKA / JUNCTION D586 540,000.00 E858 E861(SANKURI)-C81(NUNO) 300,000.00 E861 WARABLE-A3-D586 9,782,000.00 URP1 A3-DB Fafi 256,000.00 URP23 C81(FUNGICH)-BALIGE 240,000.00 URP24 Labahlo-Jarjara 720,000.00 URP25 kASHA-D586(Ohio)-Dujis 480,000.00 URP26 D586(Ohio)-Block 960,000.00 URP3 C81-ABDI SAMMIT 360,000.00 URP4 MBALAMBALA-NDANYERE 1,056,000.00 Total for Dujis Const 16,470,000.00 Urban Roads Garissa Mun. -

Making Peace Under the Mango Tree a Study on the Role of Local Institutions in Conflicts Over Natural Resources in Tana Delta, Kenya

Making peace under the mango tree A study on the role of local institutions in conflicts over natural resources in Tana Delta, Kenya By Joris Cuppen s0613851 Master Thesis Human Geography Globalisation, Migration and Development Supervisor: Marcel Rutten October 2013 Radboud University Nijmegen ii Abstract In this research, conflicts over natural resources in the Tana Delta and the role of local institutions are central, with a special emphasis on the 2012/2013 clashes. In this region, conflicts between the two dominant ethnic groups, the Orma (who are predominantly herders) and the Pokomo (predominantly farmers), are common. Three types of institutions are involved with conflict management and natural resource management, namely the local administration, village elders, and peace committees. As for other regions in Kenya, the authority of elders has diminished in the past decades, whereas the local administration lacks the authority and capacity to govern the region. Therefore, peace committees can play a vital role in conflict management and natural resource management. The main natural resources which are contested in the Tana delta, are water, pasture, and farmland. Although peace committees seem fairly effective with managing cross-communal conflicts and preventing any further escalation, conflict prevention needs further priority. Cross- communal agreements to manage natural resources have been less and less the case, which is one of the main factors causing conflicts. Engagement of communities in making these agreements should be one of the priorities in the post-clashes Tana delta. As for the 2012/2013 clashes, it is likely that outside interference, either prior or during the conflict, has caused the escalation of violence, which has led to the loss of almost 200 human lives, probably because of a favourable outcome of the elections held in March 2013. -

Biodiversity in Sub-Saharan Africa and Its Islands Conservation, Management and Sustainable Use

Biodiversity in Sub-Saharan Africa and its Islands Conservation, Management and Sustainable Use Occasional Papers of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 6 IUCN - The World Conservation Union IUCN Species Survival Commission Role of the SSC The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is IUCN's primary source of the 4. To provide advice, information, and expertise to the Secretariat of the scientific and technical information required for the maintenance of biologi- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna cal diversity through the conservation of endangered and vulnerable species and Flora (CITES) and other international agreements affecting conser- of fauna and flora, whilst recommending and promoting measures for their vation of species or biological diversity. conservation, and for the management of other species of conservation con- cern. Its objective is to mobilize action to prevent the extinction of species, 5. To carry out specific tasks on behalf of the Union, including: sub-species and discrete populations of fauna and flora, thereby not only maintaining biological diversity but improving the status of endangered and • coordination of a programme of activities for the conservation of bio- vulnerable species. logical diversity within the framework of the IUCN Conservation Programme. Objectives of the SSC • promotion of the maintenance of biological diversity by monitoring 1. To participate in the further development, promotion and implementation the status of species and populations of conservation concern. of the World Conservation Strategy; to advise on the development of IUCN's Conservation Programme; to support the implementation of the • development and review of conservation action plans and priorities Programme' and to assist in the development, screening, and monitoring for species and their populations. -

Annual Report

Darwin Initiative Annual Report Important note: To be completed with reference to the Reporting Guidance Notes for Project Leaders: it is expected that this report will be about 10 pages in length, excluding annexes Submission Deadline: 30 April Darwin Project Information Project Reference 20-011 Project Title Community-based conservation and livelihoods development within Kenya’s Boni-Dodori forest ecosystem Host Country/ies Kenya Contract Holder Institution WWF - Kenya Partner institutions KFS, KWS, ZSL Darwin Grant Value £297,500 Start/end dates of project April 2013 /March 2016 Reporting period (eg Apr 2013 – Apr 2013 – Mar 2014 Mar 2014) and number (eg Annual Report 1 Annual Report 1, 2, 3) Project Leader name Kiunga Kareko Project website https://www.wwf.basecamphq.com Report author(s) and date John Bett, April 2014 Project Rationale The Boni-Dodori coastal forest ecosystem in Kenya contains a wealth of biodiversity, much of it endemic and endangered. Little is understood, however, about the biodiversity, the ecosystem services and associated opportunities for poverty reduction. The Aweer and Ijara are indigenous groups whose culture and livelihoods co-evolved with the forests. Communities were forcibly resettled in the 1960s and much of ‘their’ forests gazetted in the 1970s, which alienated their rights to the land and natural resources, and has undermined their culture, including traditional resource use. Although designated as conservation areas, the forests have been, and are being, impacted by illegal logging, unplanned development and agricultural expansion. The Aweer have been forced into shifting cultivation which they practice along the corridor where they were resettled, and predictably human- wildlife conflicts have intensified here. -

Economic Analysis of Climate Change Adaptation Strategies at Community Farm-Level in Ijara, Garissa County, Kenya

ECONOMIC ANALYSIS OF CLIMATE CHANGE ADAPTATION STRATEGIES AT COMMUNITY FARM-LEVEL IN IJARA, GARISSA COUNTY, KENYA JOSEPH MWAURA (MENV&DEV) REG. NO. N85/27033/2011 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (CLIMATE CHANGE AND SUSTAINABILITY) IN THE SCHOOL OF ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES OF KENYATTA UNIVERSITY AUGUST, 2015 DECLARATION Declaration by candidate: This thesis is my original work and has not been presented for a degree or award in any other university Signed: ________________________________________Date____________________ Mwaura Joseph M. Reg. No. N85/27033/2011 Department of Environmental Education, Kenyatta University Declaration by supervisors: We confirm that the work reported in this thesis was carried out by the candidate under our supervision Signature__________________________ Date_____________________ Dr James KA Koske Department of Environmental Education, Kenyatta University Signature_____________________________ Date________________ Dr Bett Kiprotich Department of Agribusiness Management and Trade, Kenyatta University ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to Winnie and Helen and to all their age mates. Decisions made today on sustainable adaptation to impacts of climate change and variability mean much more to them. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I owe my indebted gratitude to Dr James Koske and Dr Bett Kiprotich, my supervisors whose assistance, guidance, and patience throughout the study are invaluable. My special thanks go to Dr. John Maingi for reading the thesis and for offering vital insight. Also the technical support accorded me by Mr. Peter Githunguri and Mr. Ronald Nyaseti all of Garissa County is appreciated. Similar gratitude goes to Mr Jamleck Ndambiri, Head N.E region conservancy, Mr Hanshi Abdi regional Director of Environment for logistical and technical support. -

THE AFRICAN LION (Panthera Leo Leo): a CONTINENT-WIDE SPECIES DISTRIBUTION STUDY and POPULATION ANALYSIS

THE AFRICAN LION (Panthera leo leo): A CONTINENT-WIDE SPECIES DISTRIBUTION STUDY AND POPULATION ANALYSIS by Jason S. Riggio Dr. Stuart L. Pimm, Advisor May 2011 Masters project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Environmental Management degree in the Nicholas School of the Environment of Duke University 2011 Abstract Human population growth and land conversion across Africa makes the future of wide-ranging carnivores uncertain. For example, the African lion (Panthera leo leo) once ranged across the entire con- tinent – with the exception of the Sahara Desert and rainforests. It now lives in less than a quarter of its historic range. Recent research estimates a loss of nearly half of the lions in the past two decades. Some sources put their numbers as low as 20,000 individuals. Given these declines, conservation organ- izations propose to list the African lion as “endangered” under the U.S. Endangered Species Act and to upgrade the species’ CITES protections from Appendix II to Appendix I. To establish the lion’s current conservation status, I analyzed the size, distribution, and potential connections of populations across its range in Africa. It is particularly important to identify connected sub-populations and areas that can serve as corridors between existing protected areas. I compile the most current scientific literature, comparing sources to identify a current population estimate. I also use these sources to map known lion populations, potential habitat patches, and the connections between them. Finally, I assess the long-term viability of each lion population and determine which qualify as “lion strongholds.” The lion population assessment in this study has shown that over 30,000 lions remain in approx- imately 3,000,000 km2 of Africa. -

Pdf | 503.01 Kb

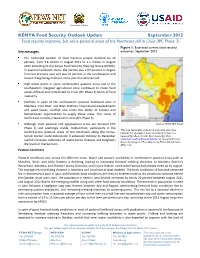

Government of Kenya KENYA Food Security Outlook Update September 2012 Food security improves, but some pastoral areas of the Northeast still in Crisis (IPC Phase 3) Figure 1. Estimated current food security Key messages outcomes, September 2012 The estimated number of food insecure people declined by 43 percent, from 3.8 million in August 2011 to 2.1 million in August 2012 according to the Kenya Food Security Steering Group (KFSSG). In pastoral livelihood zones, the decline was a 69 percent in August from the previous year and was 31 percent in the southeastern and coastal marginal agricultural zones over the same period. High maize prices in some northeastern pastoral areas and in the southeastern marginal agricultural zone continued to make food access difficult and contributed to Crisis (IPC Phase 3) levels of food insecurity. Conflicts in parts of the northeastern pastoral livelihood zone in Mandera, Tana River, and Wajir Districts, have caused displacements and asset losses. Conflict also limits the ability of traders and humanitarian organizations to supply these areas. The zones of conflict are currently classified in Crisis (IPC Phase 3). Although most pastoral and agropastoral areas are Stressed (IPC Source: FEWS NET Kenya Phase 2) and seemingly stable, malnutrition, particularly in the This map represents acute food insecurity outcomes conflict-prone pastoral areas of the Northeast along the Kenya- relevant for emergency decision-making. It does not Somali border could deteriorate if enhanced October to December necessarily reflect chronic food insecurity. Visit rainfall increases outbreaks of water-borne diseases and heightens www.fews.net/FoodInsecurityScale for more informaoin about the Integrated Food Insecurity Phase Classification the levels of malnutrition.