Chapter 5 Basics of Euclidean Geometry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A New Description of Space and Time Using Clifford Multivectors

A new description of space and time using Clifford multivectors James M. Chappell† , Nicolangelo Iannella† , Azhar Iqbal† , Mark Chappell‡ , Derek Abbott† †School of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, University of Adelaide, South Australia 5005, Australia ‡Griffith Institute, Griffith University, Queensland 4122, Australia Abstract Following the development of the special theory of relativity in 1905, Minkowski pro- posed a unified space and time structure consisting of three space dimensions and one time dimension, with relativistic effects then being natural consequences of this space- time geometry. In this paper, we illustrate how Clifford’s geometric algebra that utilizes multivectors to represent spacetime, provides an elegant mathematical framework for the study of relativistic phenomena. We show, with several examples, how the application of geometric algebra leads to the correct relativistic description of the physical phenomena being considered. This approach not only provides a compact mathematical representa- tion to tackle such phenomena, but also suggests some novel insights into the nature of time. Keywords: Geometric algebra, Clifford space, Spacetime, Multivectors, Algebraic framework 1. Introduction The physical world, based on early investigations, was deemed to possess three inde- pendent freedoms of translation, referred to as the three dimensions of space. This naive conclusion is also supported by more sophisticated analysis such as the existence of only five regular polyhedra and the inverse square force laws. If we lived in a world with four spatial dimensions, for example, we would be able to construct six regular solids, and in arXiv:1205.5195v2 [math-ph] 11 Oct 2012 five dimensions and above we would find only three [1]. -

Projective Geometry: a Short Introduction

Projective Geometry: A Short Introduction Lecture Notes Edmond Boyer Master MOSIG Introduction to Projective Geometry Contents 1 Introduction 2 1.1 Objective . .2 1.2 Historical Background . .3 1.3 Bibliography . .4 2 Projective Spaces 5 2.1 Definitions . .5 2.2 Properties . .8 2.3 The hyperplane at infinity . 12 3 The projective line 13 3.1 Introduction . 13 3.2 Projective transformation of P1 ................... 14 3.3 The cross-ratio . 14 4 The projective plane 17 4.1 Points and lines . 17 4.2 Line at infinity . 18 4.3 Homographies . 19 4.4 Conics . 20 4.5 Affine transformations . 22 4.6 Euclidean transformations . 22 4.7 Particular transformations . 24 4.8 Transformation hierarchy . 25 Grenoble Universities 1 Master MOSIG Introduction to Projective Geometry Chapter 1 Introduction 1.1 Objective The objective of this course is to give basic notions and intuitions on projective geometry. The interest of projective geometry arises in several visual comput- ing domains, in particular computer vision modelling and computer graphics. It provides a mathematical formalism to describe the geometry of cameras and the associated transformations, hence enabling the design of computational ap- proaches that manipulates 2D projections of 3D objects. In that respect, a fundamental aspect is the fact that objects at infinity can be represented and manipulated with projective geometry and this in contrast to the Euclidean geometry. This allows perspective deformations to be represented as projective transformations. Figure 1.1: Example of perspective deformation or 2D projective transforma- tion. Another argument is that Euclidean geometry is sometimes difficult to use in algorithms, with particular cases arising from non-generic situations (e.g. -

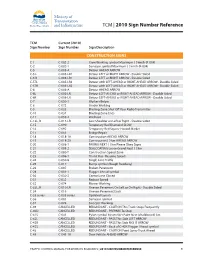

2010 Sign Number Reference for Traffic Control Manual

TCM | 2010 Sign Number Reference TCM Current (2010) Sign Number Sign Number Sign Description CONSTRUCTION SIGNS C-1 C-002-2 Crew Working symbol Maximum ( ) km/h (R-004) C-2 C-002-1 Surveyor symbol Maximum ( ) km/h (R-004) C-5 C-005-A Detour AHEAD ARROW C-5 L C-005-LR1 Detour LEFT or RIGHT ARROW - Double Sided C-5 R C-005-LR1 Detour LEFT or RIGHT ARROW - Double Sided C-5TL C-005-LR2 Detour with LEFT-AHEAD or RIGHT-AHEAD ARROW - Double Sided C-5TR C-005-LR2 Detour with LEFT-AHEAD or RIGHT-AHEAD ARROW - Double Sided C-6 C-006-A Detour AHEAD ARROW C-6L C-006-LR Detour LEFT-AHEAD or RIGHT-AHEAD ARROW - Double Sided C-6R C-006-LR Detour LEFT-AHEAD or RIGHT-AHEAD ARROW - Double Sided C-7 C-050-1 Workers Below C-8 C-072 Grader Working C-9 C-033 Blasting Zone Shut Off Your Radio Transmitter C-10 C-034 Blasting Zone Ends C-11 C-059-2 Washout C-13L, R C-013-LR Low Shoulder on Left or Right - Double Sided C-15 C-090 Temporary Red Diamond SLOW C-16 C-092 Temporary Red Square Hazard Marker C-17 C-051 Bridge Repair C-18 C-018-1A Construction AHEAD ARROW C-19 C-018-2A Construction ( ) km AHEAD ARROW C-20 C-008-1 PAVING NEXT ( ) km Please Obey Signs C-21 C-008-2 SEALCOATING Loose Gravel Next ( ) km C-22 C-080-T Construction Speed Zone C-23 C-086-1 Thank You - Resume Speed C-24 C-030-8 Single Lane Traffic C-25 C-017 Bump symbol (Rough Roadway) C-26 C-007 Broken Pavement C-28 C-001-1 Flagger Ahead symbol C-30 C-030-2 Centre Lane Closed C-31 C-032 Reduce Speed C-32 C-074 Mower Working C-33L, R C-010-LR Uneven Pavement On Left or On Right - Double Sided C-34 -

Lecture 4: April 8, 2021 1 Orthogonality and Orthonormality

Mathematical Toolkit Spring 2021 Lecture 4: April 8, 2021 Lecturer: Avrim Blum (notes based on notes from Madhur Tulsiani) 1 Orthogonality and orthonormality Definition 1.1 Two vectors u, v in an inner product space are said to be orthogonal if hu, vi = 0. A set of vectors S ⊆ V is said to consist of mutually orthogonal vectors if hu, vi = 0 for all u 6= v, u, v 2 S. A set of S ⊆ V is said to be orthonormal if hu, vi = 0 for all u 6= v, u, v 2 S and kuk = 1 for all u 2 S. Proposition 1.2 A set S ⊆ V n f0V g consisting of mutually orthogonal vectors is linearly inde- pendent. Proposition 1.3 (Gram-Schmidt orthogonalization) Given a finite set fv1,..., vng of linearly independent vectors, there exists a set of orthonormal vectors fw1,..., wng such that Span (fw1,..., wng) = Span (fv1,..., vng) . Proof: By induction. The case with one vector is trivial. Given the statement for k vectors and orthonormal fw1,..., wkg such that Span (fw1,..., wkg) = Span (fv1,..., vkg) , define k u + u = v − hw , v i · w and w = k 1 . k+1 k+1 ∑ i k+1 i k+1 k k i=1 uk+1 We can now check that the set fw1,..., wk+1g satisfies the required conditions. Unit length is clear, so let’s check orthogonality: k uk+1, wj = vk+1, wj − ∑ hwi, vk+1i · wi, wj = vk+1, wj − wj, vk+1 = 0. i=1 Corollary 1.4 Every finite dimensional inner product space has an orthonormal basis. -

Glossary of Linear Algebra Terms

INNER PRODUCT SPACES AND THE GRAM-SCHMIDT PROCESS A. HAVENS 1. The Dot Product and Orthogonality 1.1. Review of the Dot Product. We first recall the notion of the dot product, which gives us a familiar example of an inner product structure on the real vector spaces Rn. This product is connected to the Euclidean geometry of Rn, via lengths and angles measured in Rn. Later, we will introduce inner product spaces in general, and use their structure to define general notions of length and angle on other vector spaces. Definition 1.1. The dot product of real n-vectors in the Euclidean vector space Rn is the scalar product · : Rn × Rn ! R given by the rule n n ! n X X X (u; v) = uiei; viei 7! uivi : i=1 i=1 i n Here BS := (e1;:::; en) is the standard basis of R . With respect to our conventions on basis and matrix multiplication, we may also express the dot product as the matrix-vector product 2 3 v1 6 7 t î ó 6 . 7 u v = u1 : : : un 6 . 7 : 4 5 vn It is a good exercise to verify the following proposition. Proposition 1.1. Let u; v; w 2 Rn be any real n-vectors, and s; t 2 R be any scalars. The Euclidean dot product (u; v) 7! u · v satisfies the following properties. (i:) The dot product is symmetric: u · v = v · u. (ii:) The dot product is bilinear: • (su) · v = s(u · v) = u · (sv), • (u + v) · w = u · w + v · w. -

4 Jul 2018 Is Spacetime As Physical As Is Space?

Is spacetime as physical as is space? Mayeul Arminjon Univ. Grenoble Alpes, CNRS, Grenoble INP, 3SR, F-38000 Grenoble, France Abstract Two questions are investigated by looking successively at classical me- chanics, special relativity, and relativistic gravity: first, how is space re- lated with spacetime? The proposed answer is that each given reference fluid, that is a congruence of reference trajectories, defines a physical space. The points of that space are formally defined to be the world lines of the congruence. That space can be endowed with a natural structure of 3-D differentiable manifold, thus giving rise to a simple notion of spatial tensor — namely, a tensor on the space manifold. The second question is: does the geometric structure of the spacetime determine the physics, in particular, does it determine its relativistic or preferred- frame character? We find that it does not, for different physics (either relativistic or not) may be defined on the same spacetime structure — and also, the same physics can be implemented on different spacetime structures. MSC: 70A05 [Mechanics of particles and systems: Axiomatics, founda- tions] 70B05 [Mechanics of particles and systems: Kinematics of a particle] 83A05 [Relativity and gravitational theory: Special relativity] 83D05 [Relativity and gravitational theory: Relativistic gravitational theories other than Einstein’s] Keywords: Affine space; classical mechanics; special relativity; relativis- arXiv:1807.01997v1 [gr-qc] 4 Jul 2018 tic gravity; reference fluid. 1 Introduction and Summary What is more “physical”: space or spacetime? Today, many physicists would vote for the second one. Whereas, still in 1905, spacetime was not a known concept. It has been since realized that, even in classical mechanics, space and time are coupled: already in the minimum sense that space does not exist 1 without time and vice-versa, and also through the Galileo transformation. -

Lecture 3: Geometry

E-320: Teaching Math with a Historical Perspective Oliver Knill, 2010-2015 Lecture 3: Geometry Geometry is the science of shape, size and symmetry. While arithmetic dealt with numerical structures, geometry deals with metric structures. Geometry is one of the oldest mathemati- cal disciplines and early geometry has relations with arithmetics: we have seen that that the implementation of a commutative multiplication on the natural numbers is rooted from an inter- pretation of n × m as an area of a shape that is invariant under rotational symmetry. Number systems built upon the natural numbers inherit this. Identities like the Pythagorean triples 32 +42 = 52 were interpreted geometrically. The right angle is the most "symmetric" angle apart from 0. Symmetry manifests itself in quantities which are invariant. Invariants are one the most central aspects of geometry. Felix Klein's Erlanger program uses symmetry to classify geome- tries depending on how large the symmetries of the shapes are. In this lecture, we look at a few results which can all be stated in terms of invariants. In the presentation as well as the worksheet part of this lecture, we will work us through smaller miracles like special points in triangles as well as a couple of gems: Pythagoras, Thales,Hippocrates, Feuerbach, Pappus, Morley, Butterfly which illustrate the importance of symmetry. Much of geometry is based on our ability to measure length, the distance between two points. A modern way to measure distance is to determine how long light needs to get from one point to the other. This geodesic distance generalizes to curved spaces like the sphere and is also a practical way to measure distances, for example with lasers. -

Notes 20: Afine Geometry

Notes 20: Afine Geometry Example 1. Let C be the curve in R2 defined by x2 + 4xy + y2 + y2 − 1 = 0 = (x + 2y)2 + y2 − 1: If we set u = x + 2y; v = y; we obtain u2 + v2 − 1 = 0 which is a circle in the u; v plane. Let 2 2 F : R ! R ; (x; y) 7! (u = 2x + y; v = y): We look at the geometry of F: Angles: This transformation does not preserve angles. For example the line 2x + y = 0 is mapped to the line u = 0; and the line y = 0 is mapped to v = 0: The two lines in the x − y plane are not orthogonal, while the lines in the u − v plane are orthogonal. Distances: This transformation does not preserve distance. The point A = (−1=2; 1) is mapped to a = (0; 1) and the point B = (0; 0) is mapped to b = (0; 0): the distance AB is not equal to the distance ab: Circles: The curve C is an ellipse with axis along the lines 2x + y = 0 and x = 0: It is mapped to the unit circle in the u − v plane. Lines: The map is a one-to-one onto map that maps lines to lines. What is a Geometry? We can think of a geometry as having three parts: A set of points, a special set of subsets called lines, and a group of transformations of the set of points that maps lines to lines. In the case of Euclidean geometry, the set of points is the familiar plane R2: The special subsets are what we ordinarily call lines. -

Affine and Euclidean Geometry Affine and Projective Geometry, E

AFFINE AND PROJECTIVE GEOMETRY, E. Rosado & S.L. Rueda CHAPTER II: AFFINE AND EUCLIDEAN GEOMETRY AFFINE AND PROJECTIVE GEOMETRY, E. Rosado & S.L. Rueda 1. AFFINE SPACE 1.1 Definition of affine space A real affine space is a triple (A; V; φ) where A is a set of points, V is a real vector space and φ: A × A −! V is a map verifying: 1. 8P 2 A and 8u 2 V there exists a unique Q 2 A such that φ(P; Q) = u: 2. φ(P; Q) + φ(Q; R) = φ(P; R) for everyP; Q; R 2 A. Notation. We will write φ(P; Q) = PQ. The elements contained on the set A are called points of A and we will say that V is the vector space associated to the affine space (A; V; φ). We define the dimension of the affine space (A; V; φ) as dim A = dim V: AFFINE AND PROJECTIVE GEOMETRY, E. Rosado & S.L. Rueda Examples 1. Every vector space V is an affine space with associated vector space V . Indeed, in the triple (A; V; φ), A =V and the map φ is given by φ: A × A −! V; φ(u; v) = v − u: 2. According to the previous example, (R2; R2; φ) is an affine space of dimension 2, (R3; R3; φ) is an affine space of dimension 3. In general (Rn; Rn; φ) is an affine space of dimension n. 1.1.1 Properties of affine spaces Let (A; V; φ) be a real affine space. The following statemens hold: 1. -

Calculus Terminology

AP Calculus BC Calculus Terminology Absolute Convergence Asymptote Continued Sum Absolute Maximum Average Rate of Change Continuous Function Absolute Minimum Average Value of a Function Continuously Differentiable Function Absolutely Convergent Axis of Rotation Converge Acceleration Boundary Value Problem Converge Absolutely Alternating Series Bounded Function Converge Conditionally Alternating Series Remainder Bounded Sequence Convergence Tests Alternating Series Test Bounds of Integration Convergent Sequence Analytic Methods Calculus Convergent Series Annulus Cartesian Form Critical Number Antiderivative of a Function Cavalieri’s Principle Critical Point Approximation by Differentials Center of Mass Formula Critical Value Arc Length of a Curve Centroid Curly d Area below a Curve Chain Rule Curve Area between Curves Comparison Test Curve Sketching Area of an Ellipse Concave Cusp Area of a Parabolic Segment Concave Down Cylindrical Shell Method Area under a Curve Concave Up Decreasing Function Area Using Parametric Equations Conditional Convergence Definite Integral Area Using Polar Coordinates Constant Term Definite Integral Rules Degenerate Divergent Series Function Operations Del Operator e Fundamental Theorem of Calculus Deleted Neighborhood Ellipsoid GLB Derivative End Behavior Global Maximum Derivative of a Power Series Essential Discontinuity Global Minimum Derivative Rules Explicit Differentiation Golden Spiral Difference Quotient Explicit Function Graphic Methods Differentiable Exponential Decay Greatest Lower Bound Differential -

Orthogonality Handout

3.8 (SUPPLEMENT) | ORTHOGONALITY OF EIGENFUNCTIONS We now develop some properties of eigenfunctions, to be used in Chapter 9 for Fourier Series and Partial Differential Equations. 1. Definition of Orthogonality R b We say functions f(x) and g(x) are orthogonal on a < x < b if a f(x)g(x) dx = 0 . [Motivation: Let's approximate the integral with a Riemann sum, as follows. Take a large integer N, put h = (b − a)=N and partition the interval a < x < b by defining x1 = a + h; x2 = a + 2h; : : : ; xN = a + Nh = b. Then Z b f(x)g(x) dx ≈ f(x1)g(x1)h + ··· + f(xN )g(xN )h a = (uN · vN )h where uN = (f(x1); : : : ; f(xN )) and vN = (g(x1); : : : ; g(xN )) are vectors containing the values of f and g. The vectors uN and vN are said to be orthogonal (or perpendicular) if their dot product equals zero (uN ·vN = 0), and so when we let N ! 1 in the above formula it makes R b sense to say the functions f and g are orthogonal when the integral a f(x)g(x) dx equals zero.] R π 1 2 π Example. sin x and cos x are orthogonal on −π < x < π, since −π sin x cos x dx = 2 sin x −π = 0. 2. Integration Lemma Suppose functions Xn(x) and Xm(x) satisfy the differential equations 00 Xn + λnXn = 0; a < x < b; 00 Xm + λmXm = 0; a < x < b; for some numbers λn; λm. Then Z b 0 0 b (λn − λm) Xn(x)Xm(x) dx = [Xn(x)Xm(x) − Xn(x)Xm(x)]a: a Proof. -

(Finite Affine Geometry) References • Bennett, Affine An

MATHEMATICS 152, FALL 2003 METHODS OF DISCRETE MATHEMATICS Outline #7 (Finite Affine Geometry) References • Bennett, Affine and Projective Geometry, Chapter 3. This book, avail- able in Cabot Library, covers all the proofs and has nice diagrams. • “Faculty Senate Affine Geometry”(attached). This has all the steps for each proof, but no diagrams. There are numerous references to diagrams on the course Web site, however, and the combination of this document and the Web site should be all that you need. • The course Web site, AffineDiagrams folder. This has links that bring up step-by-step diagrams for all key results. These diagrams will be available in class, and you are welcome to use them instead of drawing new diagrams on the blackboard. • The Windows application program affine.exe, which can be downloaded from the course Web site. • Data files for the small, medium, and large affine senates. These accom- pany affine.exe, since they are data files read by that program. The file affine.zip has everything. • PHP version of the affine geometry software. This program, written by Harvard undergraduate Luke Gustafson, runs directly off the Web and generates nice diagrams whenever you use affine geometry to do arithmetic. It also has nice built-in documentation. Choose the PHP- Programs folder on the Web site. 1. State the first four of the five axioms for a finite affine plane, using the terms “instructor” and “committee” instead of “point” and “line.” For A4 (Desargues), draw diagrams (or show the ones on the Web site) to illustrate the two cases (three parallel lines and three concurrent lines) in the Euclidean plane.