Redalyc.WINE, PRODUCT DIFFERENTIATION and TOURISM: EXPLORING the CASE of CHILE and the MAULE REGION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redalyc.Análisis Geoespacial De Servicios Básicos Para Las

Panorama Socioeconómico ISSN: 0716-1921 [email protected] Universidad de Talca Chile Mena F., Carlos; Morales H., Yohana; Gajardo V., John; Ormazábal R., Yony Análisis Geoespacial de Servicios Básicos para las Viviendas de Longaví, Retiro y Parral, Región del Maule Panorama Socioeconómico, vol. 25, núm. 35, julio-diciembre, 2007, pp. 106-116 Universidad de Talca Talca, Chile Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=39903503 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto PANORAMA SOCIOECONÓMICO AÑO 25, Nº 35, p. 106-116 (Julio-Diciembre 2007) INVESTIGACIÓN / RESEARCH Análisis Geoespacial de Servicios Básicos para las Viviendas de Longaví, Retiro y Parral, Región del Maule Geospatial Analysis of Basic Services for Homes in Longaví, Retiro and Parral, Maule Region Carlos Mena F.1, Yohana Morales H.2, John Gajardo V.2, Yony Ormazábal R.2 1Doctor. Universidad de Talca, Centro de Geomática. E-mail: [email protected] 2Magíster, Universidad de Talca, Centro de Geomática. E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] RESUMEN. El uso y aplicación de la Geomática está siendo incorporado a los procesos de planificación local y regional, fortaleciendo la gestión de las instituciones que la utilizan y de esta forma, contribuyendo al desarrollo económico y social de la población. Conocer la ubicación exacta de una carencia social en particular y su distribución en el territorio, es el punto de partida para enfrentar el problema y llevar a cabo las acciones conducentes a su solución. -

Grupo Ancoa, Colectivo Artístico-Cultural De Linares

Grupo Ancoa, colectivo artístico-cultural de Linares *Katina Vivanco Ceppi Resumen: El denominado “Grupo Ancoa” de Linares (1958-1998) fue el colectivo artístico y cultural más relevante de la Región del Maule durante el siglo xx, debido al reconocimiento nacional e internacional de los más de 25 integrantes que congregó durante su existencia. Estos trabajaron las más diversas expresiones de las artes y letras, y organizaron un sinfín de encuentros literarios y poéticos, exposiciones colectivas y ferias artísticas, cumpliendo además un rol preponderante en la fundación del Museo de Arte y Artesanía de Linares (MAAL) a partir de 1962. El presente artículo se propone dar cuenta de su quehacer e importancia respecto de la identidad cultural de la ruralidad del Maule. PalabRas clave: Grupo Ancoa, Linares, artes visuales, literatura, poesía abstRact: The so-called “Ancoa Group” of Linares (1958- 1998) was the most important artistic and cultural collective of the Maule Region during the 20th century, due to the national and international recognition received by some of its more than 25 members. They worked in the most various expressions of arts and literature, and organized a great number of literary and poetic events, collective exhibitions and artistic fairs, playing also a prevailing role in the foun- ding of the Museo de Arte y Artesanía de Linares (MAAL) since 1962. From this perspective, the article aims to give an account of the work and relevance of its members when revisiting the identity and culture of the rurality of the Maule region. KeywoRds: Ancoa Group, Linares, visual arts, literature, poetry * Licenciada en Arte mención Restauración, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. -

Wines of Chile

PREVIEWCOPY Wines of South America: Chile Version 1.0 by David Raezer and Jennifer Raezer © 2012 by Approach Guides (text, images, & illustrations, except those to which specific attribution is given) All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, without permission in writing from the publisher. Further, this book is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This book may not be resold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. Approach Guides and the Approach Guides logo are the property of Approach Guides LLC. Other marks are the prop- erty of their respective owners. Although every effort was made to ensure that the information was as accurate as possible, we accept no responsibility for any loss, damage, injury, or inconvenience sustained by anyone using this guidebook. Approach Guides New York, NY www.approachguides.com PREVIEWISBN: 978-1-936614-36-3COPY This Approach Guide was produced in collaboration with Wines of Chile. Contents Introduction Primary Grape Varieties Map of Winegrowing Regions NORTH Elqui Valley Limarí Valley CENTRAL Aconcagua Valley * Cachapoal Valley Casablanca Valley * Colchagua Valley * Curicó Valley Maipo Valley * Maule Valley San Antonio Valley * SOUTH PREVIEWCOPY Bío Bío Valley * Itata Valley Malleco Valley Vintages About Approach Guides Contact Free Updates and Enhancements More from Approach Guides More from Approach Guides Introduction Previewing this book? Please check out our enhanced preview, which offers a deeper look at this guidebook. The wines of South America continue to garner global recognition, fueled by ongoing quality im- provements and continued attractive price points. -

The Mw 8.8 Chile Earthquake of February 27, 2010

EERI Special Earthquake Report — June 2010 Learning from Earthquakes The Mw 8.8 Chile Earthquake of February 27, 2010 From March 6th to April 13th, 2010, mated to have experienced intensity ies of the gap, overlapping extensive a team organized by EERI investi- VII or stronger shaking, about 72% zones already ruptured in 1985 and gated the effects of the Chile earth- of the total population of the country, 1960. In the first month following the quake. The team was assisted lo- including five of Chile’s ten largest main shock, there were 1300 after- cally by professors and students of cities (USGS PAGER). shocks of Mw 4 or greater, with 19 in the Pontificia Universidad Católi- the range Mw 6.0-6.9. As of May 2010, the number of con- ca de Chile, the Universidad de firmed deaths stood at 521, with 56 Chile, and the Universidad Técni- persons still missing (Ministry of In- Tectonic Setting and ca Federico Santa María. GEER terior, 2010). The earthquake and Geologic Aspects (Geo-engineering Extreme Events tsunami destroyed over 81,000 dwell- Reconnaissance) contributed geo- South-central Chile is a seismically ing units and caused major damage to sciences, geology, and geotechni- active area with a convergence of another 109,000 (Ministry of Housing cal engineering findings. The Tech- nearly 70 mm/yr, almost twice that and Urban Development, 2010). Ac- nical Council on Lifeline Earthquake of the Cascadia subduction zone. cording to unconfirmed estimates, 50 Engineering (TCLEE) contributed a Large-magnitude earthquakes multi-story reinforced concrete build- report based on its reconnaissance struck along the 1500 km-long ings were severely damaged, and of April 10-17. -

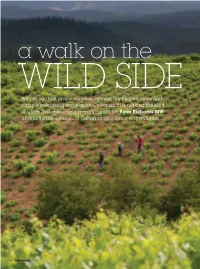

Peter Richards MW on Chile for Imbibe

a walk on the WILD SIDE With its oddball grape varieties, ancient dry-farmed vines and funky winemaking techniques, Chile’s south is making the kind of wines that restaurants are crying out for. Peter Richards MW abandons the comforts of Cabernet Sauvignon to investigate 64 imbibe.com Chile2.indd 64 4/23/2015 4:15:29 PM SOUTHERN CHILE MAIN & ABOVE: EXPLORING THE VINEYARDS OF ITATA. FAR RIGHT: HARVEST TIME AT GARCIA + SCHWADERER s Chile really worth the effort? It’s out via Carmenère, Pinot Noir and Syrah. host of other (often unidentifi ed) varieties a question – often expressed as a Yet still, the perception persists of a grew on granite soils amid rolling hills Iresigned reaction – that is fairly country that delivers solid, maybe ever- and a milder, more temperate climate widespread in the on-trade. Perhaps improving wines but which neither make than warmer areas to the north. it’s understandable, given how many the fi nest partners for food, nor have the The hills around the port city of brilliant wines from all over the globe capacity to get people excited – be they Concepción are considered Chile’s longest vie for attention in our bustling and sommeliers or diners. established vineyard, and it’s a sobering colourful marketplace, including tried This, of course, begs the question: thought that, given it was fi rst developed and tested favourites. what does get people excited when it in the mid- to late-16th century by Jesuit But it’s also based on a missionaries, this area has more conception of Chile as somewhat winemaking history than the predictable and limited in both great estates of the Médoc. -

1000 Best Wine Secrets Contains All the Information Novice and Experienced Wine Drinkers Need to Feel at Home Best in Any Restaurant, Home Or Vineyard

1000bestwine_fullcover 9/5/06 3:11 PM Page 1 1000 THE ESSENTIAL 1000 GUIDE FOR WINE LOVERS 10001000 Are you unsure about the appropriate way to taste wine at a restaurant? Or confused about which wine to order with best catfish? 1000 Best Wine Secrets contains all the information novice and experienced wine drinkers need to feel at home best in any restaurant, home or vineyard. wine An essential addition to any wine lover’s shelf! wine SECRETS INCLUDE: * Buying the perfect bottle of wine * Serving wine like a pro secrets * Wine tips from around the globe Become a Wine Connoisseur * Choosing the right bottle of wine for any occasion * Secrets to buying great wine secrets * Detecting faulty wine and sending it back * Insider secrets about * Understanding wine labels wines from around the world If you are tired of not know- * Serve and taste wine is a wine writer Carolyn Hammond ing the proper wine etiquette, like a pro and founder of the Wine Tribune. 1000 Best Wine Secrets is the She holds a diploma in Wine and * Pairing food and wine Spirits from the internationally rec- only book you will need to ognized Wine and Spirit Education become a wine connoisseur. Trust. As well as her expertise as a wine professional, Ms. Hammond is a seasoned journalist who has written for a number of major daily Cookbooks/ newspapers. She has contributed Bartending $12.95 U.S. UPC to Decanter, Decanter.com and $16.95 CAN Wine & Spirit International. hammond ISBN-13: 978-1-4022-0808-9 ISBN-10: 1-4022-0808-1 Carolyn EAN www.sourcebooks.com Hammond 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page i 1000 Best Wine Secrets 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page ii 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page iii 1000 Best Wine Secrets CAROLYN HAMMOND 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page iv Copyright © 2006 by Carolyn Hammond Cover and internal design © 2006 by Sourcebooks, Inc. -

Talking About Wine 11

11 Talking about wine 1 Put the conversation in the correct order. a 1 waiter: Would you like to order some wine with your meal? b woman: Yes, a glass of Pinot Grigio, please. c waiter: The Chardonnay is sweeter than the Sauvignon Blanc. d man: We’d like two glasses of red to go with our main course. Which is smoother, the Chianti or the Bordeaux? e waiter: Well, they are both excellent wines. I recommend the Bordeaux. It’s more full-bodied than the Chianti and it isn’t as expensive. f man: Yes, please. Which is sweeter, the Chardonnay or the Sauvignon Blanc? g man: Right. I’ll have a glass of Chardonnay, then. Sarah, you prefer something drier, don’t you? h man: OK then, let’s have the Bordeaux. i waiter: Certainly, madam. And what would you like with your main course? j woman: Yes, a bottle of sparkling water, please. k waiter: Thank you, sir. Would you like some mineral water? l 12 waiter: OK, so that’s a glass of Chardonnay, a glass of Pinot Grigio, two glasses of Bordeaux and a bottle of sparkling mineral water. 2 Find the mistakes in each sentence and correct them. 1 The Chilean Merlot is not more as expensive as the French. 2 The Riesling is sweet than the Chardonnay. 3 The Pinot Grigio is drier as the Sauvignon Blanc. 4 Chilean wine is most popular than Spanish. 5 A Chianti is no as full-bodied as a good Bordeaux. 6 Champagne is more famous the sherry. -

Análisis Espacio-Temporal De Incendios Forestales En La Región Del Maule, Chile

BOSQUE 37(1): 147-158, 2016 DOI: 10.4067/S0717-92002016000100014 Análisis espacio-temporal de incendios forestales en la región del Maule, Chile Spatio-temporal analyses of wildfires in the region of Maule, Chile Ignacio Díaz-Hormazábal a,b*, Mauro E González a *Autor de correspondencia: a Universidad Austral de Chile, Facultad de Ciencias Forestales y Recursos Naturales, Instituto de Conservación, Biodiversidad y Territorio, Laboratorio de Ecología de Bosques, casilla 567, Valdivia, Chile, [email protected] b Universidad de Chile, Facultad de Ciencias Agronómicas, Departamento de Ciencias Ambientales y Recursos Naturales, Av. Santa Rosa 11315, La Pintana, Santiago, Chile. SUMMARY In the last decades, forest fires have been a concern in different regions of the world, especially by increased occurrences product of human activities and climate changes. In this study the spatio-temporal trends in the occurrence and area affected by fire in the Maule region during the period 1986-2012 were examined. We use the Corporación Nacional Forestal fire database, whose records were spatially represented by a grid of 2x2 km. The occurrence was stable during the analyzed period with an average of 378 events per year. The burned area presented three periods above average with 5.273 hectares per year. Most of the fires affected surfaces of less than 5 hectares, while a very small number of events explain most of the area annually burned in the region. According to the startup fuel, we found an increasing number of events initiated in forest plantations in contrast to the decreasing number of fires originated in the native forests. -

Italian Wine Spanish Wine Chilean Wine

I T A L I A N W I N E Tere Nere Brunello -750ml Ilpumo Primitivo -750ml Tere Di Bio Barbaresco -750ml Casata Parini Montepulciano -750 ml Neirano Barolo -750ml Gorotti Sangiovese Merlot - 750ml Argano Toscana -750ml Primaverina Rosso -750ml Borgo Bella Toscana -750ml Nine 17 Sangiovese -750ml Barone Montalto -750ml Barone Ricasoli Chianti - 750ml Brico Al Sole Montepulciano -750ml Sermann Pinot Grigio -750ml Castorani Montepulciano -750ml Oko Organic Pinot Grigio -750 ml Terranosta Primitivo -750ml S P A N I S H W I N E La Maltida Rioja -750ml Castilo De Fuente Monastrell -750ml Lan Rioja -750ml Broken Ass Red Blend -750ml Sin Complejos Rioja -750ml Gran Vinaio -750ml Terra Unica Tempranillo -750ml Honoro Vera Granacha -750ml Miyone Granacha -750ml Xenys Monastrell -750ml Taja Monastrell -750ml Altos Rosal -750ml Campo Viejo Rioja -750ml Foresta Sauvignon Blanc -750ml C H I L E A N W I N E Toro De Piedra Cabernet Sauvignon 2015 -750ml Casa Del Toro Pinot Noir 2018 -1750 ml & 750ml Casa Del Toro Cabernet Sauvignon 1750 ml & 750ml Lanzur Merlot 2017 -750ml Lanzur Shiraz 2015 -750ml Sassy Chardonnay 2016 -750ml Sassy Merlot 2016 -750ml Layla Merlot 2015 -750ml Don Tony Perez Chardonnay -750ml Layla Chardonnay -750ml Marchigue Gran Reserva -750ml Puerto Viejo Merlot - 750ml F R E N C H W I N E Chateau Bellevue Bordeaux 2018 - 750ml Chateau De Lavagnac Bordeaux 2016 -750ml Cotes Du Rhone Loiseau 2017 -750ml Macon Vilages Mommessin 2013 -750ml Chateauneuf-Du- Pape E. Chambellan 2016 -750ml Guigal Hermitage -750ml Beaujolais- Villages Vieilles Vignes 2019 -750ml Magali Mathray Fleurie 2015 -750ml Cotes -Du _ Rhone Bonpass -750ml Bourgogne Grand Ordinare 2014 -750 ml Beaujolais - Villages Chameroy L. -

Report on Cartography in the Republic of Chile 2011 - 2015

REPORT ON CARTOGRAPHY IN CHILE: 2011 - 2015 ARMY OF CHILE MILITARY GEOGRAPHIC INSTITUTE OF CHILE REPORT ON CARTOGRAPHY IN THE REPUBLIC OF CHILE 2011 - 2015 PRESENTED BY THE CHILEAN NATIONAL COMMITTEE OF THE INTERNATIONAL CARTOGRAPHIC ASSOCIATION AT THE SIXTEENTH GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF THE INTERNATIONAL CARTOGRAPHIC ASSOCIATION AUGUST 2015 1 REPORT ON CARTOGRAPHY IN CHILE: 2011 - 2015 CONTENTS Page Contents 2 1: CHILEAN NATIONAL COMMITTEE OF THE ICA 3 1.1. Introduction 3 1.2. Chilean ICA National Committee during 2011 - 2015 5 1.3. Chile and the International Cartographic Conferences of the ICA 6 2: MULTI-INSTITUTIONAL ACTIVITIES 6 2.1 National Spatial Data Infrastructure of Chile 6 2.2. Pan-American Institute for Geography and History – PAIGH 8 2.3. SSOT: Chilean Satellite 9 3: STATE AND PUBLIC INSTITUTIONS 10 3.1. Military Geographic Institute - IGM 10 3.2. Hydrographic and Oceanographic Service of the Chilean Navy – SHOA 12 3.3. Aero-Photogrammetric Service of the Air Force – SAF 14 3.4. Agriculture Ministry and Dependent Agencies 15 3.5. National Geological and Mining Service – SERNAGEOMIN 18 3.6. Other Government Ministries and Specialized Agencies 19 3.7. Regional and Local Government Bodies 21 4: ACADEMIC, EDUCATIONAL AND TRAINING SECTOR 21 4.1 Metropolitan Technological University – UTEM 21 4.2 Universities with Geosciences Courses 23 4.3 Military Polytechnic Academy 25 5: THE PRIVATE SECTOR 26 6: ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND ACRONYMS 28 ANNEX 1. List of SERNAGEOMIN Maps 29 ANNEX 2. Report from CENGEO (University of Talca) 37 2 REPORT ON CARTOGRAPHY IN CHILE: 2011 - 2015 PART ONE: CHILEAN NATIONAL COMMITTEE OF THE ICA 1.1: Introduction 1.1.1. -

Ilustre Municipalidad De Linares Plan De Desarrollo Comunal 2014-2018

ILUSTRE MUNICIPALIDAD DE LINARES PLAN DE DESARROLLO COMUNAL 2014-2018 Marzo 2014 PLAN DE DESARROLLO COMUNAL, ILUSTRE MUNICIPALIDAD DE LINARES CAPÍTULO 1: DIAGNÓSTICO PARTICIPATIVO 13 1. INTRODUCCIÓN 13 1.1 Presentación y fundamentación del estudio 13 1.2 ¿Qué entendemos por diagnostico participativo comunal? 14 2. ANTECEDENTES GENERALES DE LA COMUNA 15 2.1 Ubicación y límites comunales 15 2.2 Historia de la comuna 17 2.3 Situación de la comuna en el contexto regional y provincial 18 3 ANTECEDENTES FÍSICO-ESPACIALES 19 3.1 Aspectos Físicos 19 3.1.1 Geomorfología 19 3.1.2 Hidrografía 20 3.3.1 Geología 21 3.2 Clima 22 3.3 Suelos 23 3.4 Uso de suelo 24 3.4.1 Uso de suelos Agrícolas y su evolución. 25 3.5 Vegetación 25 3.6 Principales Recursos Naturales: flora, fauna, mineros, pecuarios, turísticos, agrícolas, energéticos, etc. 28 3.6.1 Flora 28 3.6.2 Fauna 30 3.7 Recursos Turísticos 30 3.7.1 Método CICATUR OEA 37 3.8 Análisis de Riesgos Naturales 39 3.8.1 Riesgos de movimientos en masa 39 3.8.2 Riesgo de Inundación 41 3.8.3 Riesgo volcánico 43 3.9 Análisis de Conflictos Ambientales 44 3.9.1 Contaminación atmosférica 44 3.9.2 Centrales hidroeléctricas de paso 44 4. ANÁLISIS DEMOGRÁFICO 45 4.1 Evolución Demográfica 45 4.2 Proyecciones de población 46 4.3 Tasa de crecimiento 47 4.4 Densidad 48 PAC Consultores Ltda. | www.pac-consultores.cl 3 PLAN DE DESARROLLO COMUNAL, ILUSTRE MUNICIPALIDAD DE LINARES 4.5 Índice de masculinidad 48 4.6 Estructura etária de los habitantes 49 4.7 Movimientos migratorios 49 4.8 Estado civil de la población mayor de 14 años. -

HLSR Rodeouncorked 2014 International Wine Competition Results

HLSR RodeoUncorked 2014 International Wine Competition Results AWARD Wine Name Class Medal Region Grand Champion Best of Show, Marchesi Antinori Srl Guado al Tasso, Bolgheri DOC Superiore, 2009 Old World Bordeaux-Blend Red Double-Gold Italy Class Champion Reserve Grand Champion, Class Sonoma-Cutrer Vineyards Estate Bottled Pinot Noir, Russian River New World Pinot Noir ($23-$35) Double-Gold U.S. Champion Valley, 2010 Top Texas, Class Champion, Bending Branch Winery Estate Grown Tannat, Texas Hill Country, 2011 Tannat Double-Gold Texas Texas Class Champion Top Chilean, Class Champion, Chilean Cabernet Sauvignon ($16 and La Playa Vineyards Axel Cabernet Sauvignon, Colchagua Valley, 2011 Double-Gold Chile Chile Class Champion higher) Top Red, Class Champion Fess Parker Winery The Big Easy, Santa Barbara County, 2011 Other Rhone-Style Varietals/Blends Double-Gold U.S. Top White, Class Champion Sheldrake Point Riesling, Finger Lakes, 2011 Riesling - Semi-Dry Double-Gold U.S. Top Sparkling, Class Champion Sophora Sparkling Rose, New Zealand, NV Sparkling Rose Double-Gold New Zealand Top Sweet, Class Champion Sheldrake Point Riesling Ice Wine, Finger Lakes, 2010 Riesling-Sweet Double-Gold U.S. Top Value, Class Champion Vigilance Red Blend " Cimarron", Red Hills Lake County, 2011 Cab-Syrah/Syrah-Cab Blends Double-Gold U.S. Top Winery Michael David Winery Top Wine Outfit Trinchero Family Estates Top Chilean Wine Outfit Concha Y Toro AWARD Wine Name Class Medal Region 10 Span Chardonnay, Central Coast, California, 2012 Chardonnay wooded ($10 -$12) Silver U.S. 10 Span Pinot Gris, Monterey, California, 2012 Pinot Gris/Pinot Grigio ($11-$15) Silver U.S.