A Behavioral and Morphological Study of Sympatry in the Indigo and Lazuli Buntings of the Great Plains

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Terrestrial Ecology Enhancement

PROTECTING NESTING BIRDS BEST MANAGEMENT PRACTICES FOR VEGETATION AND CONSTRUCTION PROJECTS Version 3.0 May 2017 1 CONTENTS Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION 3 2.0 BIRDS IN PORTLAND 4 3.0 NESTING BEHAVIOR OF PORTLAND BIRDS 4 3.1 Timing 4 3.2 Nesting Habitats 5 4.0 GENERAL GUIDELINES 9 4.1 What if Work Must Occur During Avoidance Periods? 10 4.2 Who Conducts a Nesting Bird Survey? 10 5.0 SPECIFIC GUIDELINES 10 5.1 Stream Enhancement Construction Projects 10 5.2 Invasive Species Management 10 - Blackberry - Clematis - Garlic Mustard - Hawthorne - Holly and Laurel - Ivy: Ground Ivy - Ivy: Tree Ivy - Knapweed, Tansy and Thistle - Knotweed - Purple Loosestrife - Reed Canarygrass - Yellow Flag Iris 5.3 Other Vegetation Management 14 - Live Tree Removal (Native and Non-Native) - Snag Removal - Shrub Removal (Native and Non-Native) - Grassland Mowing and Ground Cover Removal (Native and Non-Native) - Controlled Burn 5.4 Other Management Activities 16 - Removing Structures - Manipulating Water Levels 6.0 SENSITIVE AREAS 17 7.0 SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS 17 7.1 Species 17 7.2 Other Things to Keep in Mind 19 Best Management Practices: Avoiding Impacts on Nesting Birds Version 3.0 –May 2017 2 8.0 WHAT IF YOU FIND AN ACTIVE NEST ON A PROJECT SITE 19 DURING PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION? 9.0 WHAT IF YOU FIND A BABY BIRD OUT OF ITS NEST? 19 10.0 SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS FOR AVOIDING 20 IMPACTS ON NESTING BIRDS DURING CONSTRUCTION AND REVEGETATION PROJECTS APPENDICES A—Average Arrival Dates for Birds in the Portland Metro Area 21 B—Nesting Birds by Habitat in Portland 22 C—Bird Nesting Season and Work Windows 25 D—Nest Buffer Best Management Practices: 26 Protocol for Bird Nest Surveys, Buffers and Monitoring E—Vegetation and Other Management Recommendations 38 F—Special Status Bird Species Most Closely Associated with Special 45 Status Habitats G— If You Find a Baby Bird Out of its Nest on a Project Site 48 H—Additional Things You Can Do To Help Native Birds 49 FIGURES AND TABLES Figure 1. -

Wildlife of the North Hills: Birds, Animals, Butterflies

Wildlife of the North Hills: Birds, Animals, Butterflies Oakland, California 2005 About this Booklet The idea for this booklet grew out of a suggestion from Anne Seasons, President of the North Hills Phoenix Association, that I compile pictures of local birds in a form that could be made available to residents of the north hills. I expanded on that idea to include other local wildlife. For purposes of this booklet, the “North Hills” is defined as that area on the Berkeley/Oakland border bounded by Claremont Avenue on the north, Tunnel Road on the south, Grizzly Peak Blvd. on the east, and Domingo Avenue on the west. The species shown here are observed, heard or tracked with some regularity in this area. The lists are not a complete record of species found: more than 50 additional bird species have been observed here, smaller rodents were included without visual verification, and the compiler lacks the training to identify reptiles, bats or additional butterflies. We would like to include additional species: advice from local experts is welcome and will speed the process. A few of the species listed fall into the category of pests; but most - whether resident or visitor - are desirable additions to the neighborhood. We hope you will enjoy using this booklet to identify the wildlife you see around you. Kay Loughman November 2005 2 Contents Birds Turkey Vulture Bewick’s Wren Red-tailed Hawk Wrentit American Kestrel Ruby-crowned Kinglet California Quail American Robin Mourning Dove Hermit thrush Rock Pigeon Northern Mockingbird Band-tailed -

Visual Displays and Their Context in the Painted Bunting

Wilson Bull., 96(3), 1984, pp. 396-407 VISUAL DISPLAYS AND THEIR CONTEXT IN THE PAINTED BUNTING SCOTT M. LANYON AND CHARLES F. THOMPSON The 12 species in the bunting genus Passerina have proved to be a popular source of material for studies of vocalizations (Rice and Thomp- son 1968; Thompson 1968, 1970, 1972; Shiovitz and Thompson 1970; Forsythe 1974; Payne 1982) migration (Emlen 1967a, b; Emlen et al. 1976) systematics (Sibley and Short 1959; Emlen et al. 1975), and mating systems (Carey and Nolan 1979, Carey 1982). Despite this interest, few detailed descriptions of the behavior of any member of this genus have been published. In this paper we describe aspects of courtship and ter- ritorial behavior of the Painted Bunting (Passerina ciris). STUDY AREA AND METHODS The study was conducted on St. Catherines Island, a barrier island approximately 50 km south of Savannah, Georgia. The 90-ha study area (“Briar Field” Thomas et al. [1978: Fig. 41) on the western side of the island borders extensive salt marshes dominated by cordgrasses (Spartina spp.). The tracts’ evergreen oak forest (Braun 1964:303) consists primarily of oaks (Quercus spp.) and pines (Pinus spp.), with scattered hickories (Carya spp.) and palmettos (Sabal spp. and Serenoe repens) also present. Undergrowth was scanty so that buntings were readily visible when on the ground. As part of a study of mating systems, more than 1800 h were devoted to watching buntings during daily fieldwork in the 1976-1979 breeding seasons. In 1976 and 1977 observations commenced the third week of May, after breeding had begun, and continued until breeding ended in early August. -

Blue Water Navy Vietnam Veterans Act of 2019

PUBLIC LAW 116–23—JUNE 25, 2019 BLUE WATER NAVY VIETNAM VETERANS ACT OF 2019 VerDate Sep 11 2014 06:12 Sep 30, 2019 Jkt 089139 PO 00023 Frm 00001 Fmt 6579 Sfmt 6579 E:\PUBLAW\PUBL023.116 PUBL023 dkrause on DSKBC28HB2PROD with PUBLAWS 133 STAT. 966 PUBLIC LAW 116–23—JUNE 25, 2019 Public Law 116–23 116th Congress An Act To amend title 38, United States Code, to clarify presumptions relating to the June 25, 2019 exposure of certain veterans who served in the vicinity of the Republic of Vietnam, [H.R. 299] and for other purposes. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of Blue Water Navy the United States of America in Congress assembled, Vietnam Veterans Act SECTION 1. SHORT TITLE. of 2019. 38 USC 101 note. This Act may be cited as the ‘‘Blue Water Navy Vietnam Veterans Act of 2019’’. SEC. 2. CLARIFICATION OF PRESUMPTIONS OF EXPOSURE FOR VET- ERANS WHO SERVED IN VICINITY OF REPUBLIC OF VIETNAM. (a) IN GENERAL.—Chapter 11 of title 38, United States Code, is amended by inserting after section 1116 the following new section: 38 USC 1116A. ‘‘§ 1116A. Presumptions of service connection for veterans who served offshore of the Republic of Vietnam Time period. ‘‘(a) SERVICE CONNECTION.—For the purposes of section 1110 of this title, and subject to section 1113 of this title, a disease covered by section 1116 of this title becoming manifest as specified in that section in a veteran who, during active military, naval, or air service, served offshore of the Republic of Vietnam during the period beginning on January 9, 1962, and ending on May 7, 1975, shall be considered to have been incurred in or aggravated by such service, notwithstanding that there is no record of evidence of such disease during the period of such service. -

Davie Blue Route and Times

TOWN OF DAVIE REVISED BLUE ROUTE (WEST) 1 2 3 4 2 5 6 7 8 7 9 10 11 12 11 13 14 15 1 West West Regional Terminal Shenandoah 136th Ave & SR 84 Orange Park Sunshine Villiage Western Hills Shenandoah Paradise Village Kings of 84Manor/South Winn 84Dixie/Plaza Rexmere Villiage Winn 84Dixie/Plaza Publix Pine Island Plaza Nob Hill RD/SR 84 Indian Ridge Middle School Publix Pine Island Plaza Pine Ridge Condos Publix Pine Island Plaza City Mobile Park Home Estates Tower Shops/Best Buy Westfield Mall West Regional Terminal 8:00 AM 8:13 AM 8:15 AM 8:18 AM 8:28 AM 8:34 AM 8:38 AM 8:45 AM 8:52 AM 8:55 AM 8:58 AM 9:06 AM 9:10 AM 9:15 AM 9:23 AM 9:30 AM 8:45 AM 8:57 AM 9:00 AM 9:09 AM 9:14 AM 9:19 AM 9:27 AM 9:30 AM 9:37 AM 9:40 AM 9:48 AM 9:51 AM 9:55 AM 10:00 AM 10:08 AM 10:15 AM 9:30 AM 9:43 AM 9:45 AM 9:48 AM 9:58 AM 10:04 AM 10:08 AM 10:15 AM 10:22 AM 10:25 AM 10:28 AM 10:36 AM 10:40 AM 10:45 AM 10:53 AM 11:00 AM 10:15 AM 10:27 AM 10:30 AM 10:39 AM 10:44 AM 10:49 AM 10:57 AM 11:00 AM 11:07 AM 11:10 AM 11:18 AM 11:21 AM 11:25 AM 11:30 AM 11:38 AM 11:45 AM 11:00 AM 11:13 AM 11:15 AM 11:18 AM 11:28 AM 11:34 AM 11:38 AM 11:45 AM 11:52 AM 11:55 AM 11:58 AM 12:06 PM 12:10 PM 12:15 PM 12:23 PM 12:30 PM 12:45 PM 12:58 PM 1:00 PM 1:03 PM 1:13 PM 1:19 PM 1:23 PM 1:30 PM 1:37 PM 1:40 PM 1:43 PM 1:51 PM 1:55 PM 2:00 PM 2:08 PM 2:15 PM 1:30 PM 1:42 PM 1:45 PM 1:54 PM 1:59 PM 2:04 PM 2:12 PM 2:15 PM 2:22 PM 2:25 PM 2:33 PM 2:36 PM 2:40 PM 2:45 PM 2:53 PM 3:00 PM 2:15 PM 2:28 PM 2:30 PM 2:33 PM 2:43 PM 2:49 PM 2:53 PM 3:00 PM 3:07 PM 3:10 PM 3:13 PM 3:21 PM 3:25 PM 3:30 PM 3:38 PM 3:45 PM 3:00 PM 3:12 PM 3:15 PM 3:24 PM 3:29 PM 3:34 PM 3:42 PM 3:45 PM 3:52 PM 3:55 PM 4:03 PM 4:05 PM 4:10 PM 4:15 PM 4:23 PM 4:30 PM 3:45 PM 3:58 PM 4:00 PM 4:03 PM 4:13 PM 4:19 PM 4:23 PM 4:30 PM 4:37 PM 4:40 PM 4:43 PM 4:51 PM 4:55 PM 5:00 PM 5:08 PM 5:15 PM Ride The Town of Davie Blue Route (West) Davie Community Bus BCT Route WEST REGIONAL 2 Dr. -

Life History Account for Lazuli Bunting

California Wildlife Habitat Relationships System California Department of Fish and Wildlife California Interagency Wildlife Task Group LAZULI BUNTING Passerina amoena Family: CARDINALIDAE Order: PASSERIFORMES Class: AVES B477 Written by: S. Granholm Reviewed by: L. Mewaldt Edited by: R. Duke DISTRIBUTION, ABUNDANCE, AND SEASONALITY A common summer visitor from April into September throughout most of California, except in higher mountains and southern deserts. Breeds in open chaparral habitats and brushy understories of open wooded habitats, especially valley foothill riparian. Also frequents thickets of willows, tangles of vines, patches of tall forbs. Often breeds on hillsides near streams or springs. In arid areas, mostly breeds in riparian habitats. May breed in tall forbs in mountain meadows (Gaines 1977b). An uncommon breeder in Central Valley, and rare and local above lower montane habitats. Small numbers move upslope after nesting, occasionally as high as 3050 m (10,000 ft). More widespread in lowlands in migration, occurring commonly in Central Valley (especially in fall) and desert oases (Grinnell and Miller 1944, McCaskie et al. 1979, 1988, Verner and Boss 1980, Garrett and Dunn 1981). SPECIFIC HABITAT REQUIREMENTS Feeding: Feeds mostly on insects and small seeds. Both are important foods through spring and summer (Martin et al. 1961, Bent 1968). Mostly forages in or beneath tall, dense herbaceous vegetation, shrubs, low tree foliage, and vine tangles. Takes insects and seeds from plants or from ground. Sometimes hawks insects in air and gleans foliage well up into tree canopy. Cover: Trees and shrubs and herbage provide cover. Male often sings from high perch in a tree, if present; otherwise uses a taller shrub (Grinnell and Miller 1944). -

Shades of Blue

Episode # 101 Script # 101 SHADES OF BLUE “Pilot” Written by Adi Hasak Directed by Barry Levinson First Network Draft January 20th, 2015 © 20____ Universal Television LLC ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. NOT TO BE DUPLICATED WITHOUT PERMISSION. This material is the property of Universal Television LLC and is intended solely for use by its personnel. The sale, copying, reproduction or exploitation of this material, in any form is prohibited. Distribution or disclosure of this material to unauthorized persons is also prohibited. PRG-17UT 1 of 1 1-14-15 TEASER FADE IN: INT. MORTUARY PREP ROOM - DAY CLOSE ON the Latino face of RAUL (44), both mortician and local gang leader, as he speaks to someone offscreen: RAUL Our choices define us. It's that simple. A hint of a tattoo pokes out from Raul's collar. His latex- gloved hand holding a needle cycles through frame. RAUL Her parents chose to name her Lucia, the light. At seven, Lucia used to climb out on her fire escape to look at the stars. By ten, Lucia could name every constellation in the Northern Hemisphere. (then) Yesterday, Lucia chose to shoot heroin. And here she lies today. Reveal that Raul is suturing the mouth of a dead YOUNG WOMAN lying supine on a funeral home prep table. As he works - RAUL Not surprising to find such a senseless loss at my doorstep. What is surprising is that Lucia picked up the hot dose from a freelancer in an area I vacated so you could protect parks and schools from the drug trade. I trusted your assurance that no one else would push into that territory. -

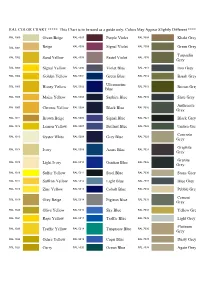

RAL COLOR CHART ***** This Chart Is to Be Used As a Guide Only. Colors May Appear Slightly Different ***** Green Beige Purple V

RAL COLOR CHART ***** This Chart is to be used as a guide only. Colors May Appear Slightly Different ***** RAL 1000 Green Beige RAL 4007 Purple Violet RAL 7008 Khaki Grey RAL 4008 RAL 7009 RAL 1001 Beige Signal Violet Green Grey Tarpaulin RAL 1002 Sand Yellow RAL 4009 Pastel Violet RAL 7010 Grey RAL 1003 Signal Yellow RAL 5000 Violet Blue RAL 7011 Iron Grey RAL 1004 Golden Yellow RAL 5001 Green Blue RAL 7012 Basalt Grey Ultramarine RAL 1005 Honey Yellow RAL 5002 RAL 7013 Brown Grey Blue RAL 1006 Maize Yellow RAL 5003 Saphire Blue RAL 7015 Slate Grey Anthracite RAL 1007 Chrome Yellow RAL 5004 Black Blue RAL 7016 Grey RAL 1011 Brown Beige RAL 5005 Signal Blue RAL 7021 Black Grey RAL 1012 Lemon Yellow RAL 5007 Brillant Blue RAL 7022 Umbra Grey Concrete RAL 1013 Oyster White RAL 5008 Grey Blue RAL 7023 Grey Graphite RAL 1014 Ivory RAL 5009 Azure Blue RAL 7024 Grey Granite RAL 1015 Light Ivory RAL 5010 Gentian Blue RAL 7026 Grey RAL 1016 Sulfer Yellow RAL 5011 Steel Blue RAL 7030 Stone Grey RAL 1017 Saffron Yellow RAL 5012 Light Blue RAL 7031 Blue Grey RAL 1018 Zinc Yellow RAL 5013 Cobolt Blue RAL 7032 Pebble Grey Cement RAL 1019 Grey Beige RAL 5014 Pigieon Blue RAL 7033 Grey RAL 1020 Olive Yellow RAL 5015 Sky Blue RAL 7034 Yellow Grey RAL 1021 Rape Yellow RAL 5017 Traffic Blue RAL 7035 Light Grey Platinum RAL 1023 Traffic Yellow RAL 5018 Turquiose Blue RAL 7036 Grey RAL 1024 Ochre Yellow RAL 5019 Capri Blue RAL 7037 Dusty Grey RAL 1027 Curry RAL 5020 Ocean Blue RAL 7038 Agate Grey RAL 1028 Melon Yellow RAL 5021 Water Blue RAL 7039 Quartz Grey -

Aou Alpha Codes for Wayne National Forest Birds 1

AOU ALPHA CODES FOR WAYNE NATIONAL FOREST BIRDS Species AOU Species AOU Alpha Alpha Code Code Acadian Flycatcher ACFL Dickcissel DICK Alder Flycatcher ALFL Double-crested Cormorant DCCO American Black Duck ABDU Downy Woodpecker DOWO American Coot AMCO Eastern Bluebird EABL American Crow AMCR Eastern Kingbird EAKI American Goldfinch AMGO Eastern Meadowlark EAME American Kestrel MAKE Eastern Phoebe EAPH American Redstart AMRE Eastern Screech Owl EASO American Robin AMRO Eastern Tufted Titmouse ETTI American Woodcock AMWO Eastern Wood-pewee EWPE Bald Eagle BAEA European Starling EUST Baltimore Oriole BAOR Field Sparrow FISP Bank Swallow BANS Golden-winged Warbler GWWA Barn Swallow BARS Grasshopper Sparrow GRSP Barred Owl BAOW Gray Catbird GRCA Bay-breasted Warbler BBWA Great Blue Heron GBHE Belted Kingfisher BEKI Great Crested Flycatcher GCFL Black Vulture BLVU Great Horned Owl GHOW Black-and-white Warbler BAWW Great Horned Owl GHOW Black-billed Cuckoo BBCU Green Heron GRHE Black-capped Chickadee BCCH Hairy Woodpecker HAWO Black-crowned Night-Heron BCNH Henslow’s Sparrow HESP Blackpoll Warbler BLPW Hermit Thrush HETH Black-throated Green Warbler BTNW Hooded Merganser HOME Blue Grosbeak BLGR Hooded Warbler HOWA Blue Jay BLJA Horned Lark HOLA Blue-gray Gnatcatcher BGGN House Finch HOFI Blue-winged Warbler BWWA House Sparrow HOSP Bobolink BOBO House Wren HOWR Broad-winged Hawk BWHA Indigo Bunting INBU Brown Thrasher BRTH Kentucky Warbler KEWA Brown-headed Cowbird BHCO Killdeer KILL Canada Goose CAGO Louisiana Waterthrush LOWA Carolina Chickadee -

Eastern Indigo Snake (Flier)

How To Distinguish Eastern Indigo Snakes Eastern indigo snakes became federally protected as threatened under the Endangered Species Act From Other Common Species in 1978, and they are also protected as threatened by Florida and Georgia. It is illegal to harass, harm, capture, keep, or kill an eastern indigo snake without specific state and/or federal permits. Life History Eastern indigo snakes use a wide variety of habitats The historic range of the eastern ranging from very wet to very dry. They tend to stay indigo snake (shown in dark green) in a specific area known as a home range, but this extended from the southern-most tip Adult eastern indigo snakes may be area is not static and can change over time, of South Carolina west through southern confused with few other species, due Georgia, Alabama, and into eastern to the indigo’s glossy blue-black probably in response to habitat conditions and Mississippi. The current range is shown in color and large size (5–7 ft.). prey availability. Because indigo snakes are sizeable light green. The eastern indigo snake (Drymarchon predators that actively hunt for their food, they couperi) has the distinction of being the need large home ranges. Males have been shown longest snake native to the United States. to use between 50 and 800 acres, whereas females often used for shelter. The snake may share the Eastern indigos typically range from 5 to 7 occupy up to 370 acres. During the winter, home burrow with a tortoise, but most often indigos will feet long, but can reach lengths greater than range sizes are smaller, particularly in the cooler occupy an old burrow that a tortoise has deserted. -

DWDM “Color” Bands for CATV Industry

Notes/Answer Question Scenario Summary Keywords © 2003Fiberdyne Labs,Inc. the DWDMchannels(andwavelengths)aredividedamongthesethree,CATV,colorbands. channels aregroupedintothree“color”bands:Blue,PurpleandRed.Thefollowingtableshowshow industry typicallyusesonlychannels19through59.WithintheCableTVindustry,theseC-Band According totheITU'sDWDMGrid,C-Bandincludeschannels1through72.However,CATV optic applications,likeCableTelevision(CATV). Bands areconvenientwaysfordescribingagroupofwavelengths,whichusedinvariousfiber- defined bytheInternationalTelecommunicationUnion(ITU)“Grid,”as1520.25-nmto1577.03-nm. Band) iscenteredat1550-nm.TheC-band,forDenseWavelengthDivisionMultiplexing(DWDM), Fiber-optic wavelengthsaredividedintoseveral“bands.”Forexample,theC-Band(orConventional- Which DWDMchannelsarerepresentedbywhichcolor“band?” Purple andRed. A CableTVproviderasksforDWDMmodule.Thechannelsarespecifiedusingthecolors:Blue, Red channels.Thenarrowsection,whichdividestheandBlue,includesPurple Red. Basically,thelowerhalf,ofC-Band,includesbluechannels.Theupperhalf For fiber-optic,Cable-TVpurposes,the“C-band”isdividedintothreecolor“bands:”Blue,Purpleand Application, CATV,DWDM,Fiber-optics that onebanddoesnotoverlap anotherband. Purple bandisusedasa“guard band.”Aguardbandisarelativelylargeseparation, whichensures channels, intotheaboveRed andBluegroups.Insomeapplications,liketheRed/Blue filter,the Note Or, graphically.... C h # : someofFiberdyne'sDWDM productsusea“Red/Blue”filter.Thisfilterdivides theITUGrid : 59 Channel Numbers 58 57 59 to45 56 35 to19 43 to37 55 54 B 53 L DWDM “Color”BandsforCATVIndustry 52 U 51 E 50 49 48 47 Application Note Wavelengths (nm) 1530.33 to1541.35 46 1549.32 to1562.23 1542.94 to1547.72 www.fiberdyne.com 45 43 P 42 U 41 R 40 P 39 L 38 E 37 35 34 33 CATV ColorBand 32 AN3023 Rev B, Page 31 30 Purple Blue Red 29 R 28 E 27 D 26 25 24 23 22 1 21 of 20 1 19. -

Wildland Fire in Ecosystems: Effects of Fire on Fauna

United States Department of Agriculture Wildland Fire in Forest Service Rocky Mountain Ecosystems Research Station General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-42- volume 1 Effects of Fire on Fauna January 2000 Abstract _____________________________________ Smith, Jane Kapler, ed. 2000. Wildland fire in ecosystems: effects of fire on fauna. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-42-vol. 1. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 83 p. Fires affect animals mainly through effects on their habitat. Fires often cause short-term increases in wildlife foods that contribute to increases in populations of some animals. These increases are moderated by the animals’ ability to thrive in the altered, often simplified, structure of the postfire environment. The extent of fire effects on animal communities generally depends on the extent of change in habitat structure and species composition caused by fire. Stand-replacement fires usually cause greater changes in the faunal communities of forests than in those of grasslands. Within forests, stand- replacement fires usually alter the animal community more dramatically than understory fires. Animal species are adapted to survive the pattern of fire frequency, season, size, severity, and uniformity that characterized their habitat in presettlement times. When fire frequency increases or decreases substantially or fire severity changes from presettlement patterns, habitat for many animal species declines. Keywords: fire effects, fire management, fire regime, habitat, succession, wildlife The volumes in “The Rainbow Series” will be published during the year 2000. To order, check the box or boxes below, fill in the address form, and send to the mailing address listed below.