Making Sense of Nonsense in Irish Vocal Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Or Download Full Colour Catalogue May 2021

VIEW OR DOWNLOAD FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE 1986 — 2021 CELEBRATING 35 YEARS Ian Green - Elaine Sunter Managing Director Accounts, Royalties & Promotion & Promotion. ([email protected]) ([email protected]) Orders & General Enquiries To:- Tel (0)1875 814155 email - [email protected] • Website – www.greentrax.com GREENTRAX RECORDINGS LIMITED Cockenzie Business Centre Edinburgh Road, Cockenzie, East Lothian Scotland EH32 0XL tel : 01875 814155 / fax : 01875 813545 THIS IS OUR DOWNLOAD AND VIEW FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE FOR DETAILS OF AVAILABILITY AND ON WHICH FORMATS (CD AND OR DOWNLOAD/STREAMING) SEE OUR DOWNLOAD TEXT (NUMERICAL LIST) CATALOGUE (BELOW). AWARDS AND HONOURS BESTOWED ON GREENTRAX RECORDINGS AND Dr IAN GREEN Honorary Degree of Doctorate of Music from the Royal Conservatoire, Glasgow (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – The Hamish Henderson Award for Services to Traditional Music (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – Hall of Fame (Ian Green) East Lothian Business Annual Achievement Award For Good Business Practises (Greentrax Recordings) Midlothian and East Lothian Chamber of Commerce – Local Business Hero Award (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Hands Up For Trad – Landmark Award (Greentrax Recordings) Featured on Scottish Television’s ‘Artery’ Series (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Honorary Member of The Traditional Music and Song Association of Scotland and Haddington Pipe Band (Ian Green) ‘Fuzz to Folk – Trax of My Life’ – Biography of Ian Green Published by Luath Press. Music Type Groups : Traditional & Contemporary, Instrumental -

Opiate Abuse and the Growing Impact on Maternal and Child Health in West Virginia Overview

Opiate Abuse and the Growing Impact on Maternal and Child Health in West Virginia Christina Mullins, Director Office of Maternal, Child and Family Health Bureau for Public Health October 23, 2017 Mullins Overview • Describe the epidemic in West Virginia. • Discuss the collaborative relationships used to develop the Drug Free Moms and Babies Project. • Provide an overview of key strategies and results. • Discuss lessons learned. Mullins 1 1 Drug Overdose Rates by State US Resident Overdose Deaths by State, 2015 14.7 13.8 8.6 21.2 12.0 10.6 14.2 15.5 8.4 13.6 NH – 34.3 16.4 20.4 VT – 16.7 10.3 26.3 MA – 25.7 6.9 20.4 29.9 RI – 28.2 23.4 14.1 19.5 15.4 41.5 CT – 22.1 11.3 11.8 17.9 12.4 NJ – 16.3 29.9 DE – 22.0 15.8 MD – 20.9 19.0 19.0 22.2 25.3 13.8 15.7 DC – 18.6 12.3 15.7 12.7 9.4 19.0 16.0 16.2 West Virginia # 1 41.5 deaths per Age‐Adjusted Rate Per 100,000 Population 100,000 11.3 6.9 – 12.7 16.4 – 21.2 US Rate – 16.3 Data Source: CDC Wonder 12.8 – 16.3 21.3 – 41.5 2 Mullins West Virginia vs. United States 2001‐2015 Resident Drug Overdose Mortality Rate West Virginia and United States WV 45 41.5 40 36.3 35.5 35 32.0 32.2 28.9 30 25.9 25.7 22.3 22.4 25 20.4 Per 100,000 18.8 20 15.1 12.9 15 11.5 16.3 14.7 13.2 13.1 13.8 10 11.5 11.9 11.9 11.9 12.3 10.1 8.2 8.9 9.4 5 6.8 0 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 Data Source: WV Health Statistics Center, Vital Surveillance System and CDC Wonder Rates are adjusted by age to the 2000 US Standard Million. -

SCQF Level 6 Bagpipes Practical

Z The Royal Scottish Pipe Band Association Pipe Band College Certification Education Guidelines PDQB CERTIFICATE - SCQF 6 Bagpipes This guide is intended for both Students and Instructors. It must be read in conjunction with SCQF 6 Bagpipes Syllabus to ensure all aspects are covered. Refer www.pdqb.org. It is strongly recommended that all students sitting this level have access to the RSPBA Structured Learning Books. It is also recommended to purchase The College of Piping Tutor 4 – Piobaireachd be purchased. It is therefore important that Instructors use these recommended books as their main source material. The RSPBA Structured Learning Books are available free from the RSPBA Pipe Band College :- https://www.rspba.org/ Obtain College of Piping Tutor 4 Knowledge of SCQF 2 through 5 are essential for SCQF 6. Students who start at SCQF 6 may be required to prove competency of prior levels by the Examiner. Be prepared for this. Theory Aspects: • Write bars of a monotone rhythm in various combinations e.g. Compound Duple time / Cut Common time / Common time etc. And be able to consider rests in the combinations and ensure each bar has different combination of note values. • Explain the accent pattern in reels and describe two important factors in reel playing – could be any type of tune – say Reel or Strathspey etc– accent pattern - Simple Duple Time meaning 2 beats in the Bar SW for reel or Simple Quadruple Time SWMW for Strathspey etc. – important factors in playing different types of tunes – discuss this e.g. good technique, appropriate tempo, decision of round or dot cut etc. -

Reel of the 51St Division

Published by the LONDON BRANCH of the ROYAL SCOTTISH COUNTRY DANCE SOCIETY www. rscdslondon.org.uk Registered Charity number 1067690 Dancing is FUN! No 260 MAY to AUGUST 2007 ANNUAL GENERAL SUMMER PICNIC DANCE MEETING In the Grounds of Harrow School The AGM of the Royal Scottish Country Saturday 30 June 2007 from 2.00-6.00pm. Dancing to David Hall and his Band Dance Society London Branch will be held at The nearest underground station is Harrow on the Hill. St Columba's Church (Upper Hall), Pont Programme Harrow School is 10 to 15 minutes walk east along Street, London, SWI on Friday 15 June 2007. The Dashing White Sergeant .............. 2/2 Lowlands Road (A404) and then right into Peterborough Tea will be served at 6pm and the meeting will The Happy Meeting ......................... 29/9 Road to Garlands Lane, first on left. The 258 bus from commence at 7pm. There will be dancing after Monymusk ...................................... 11/2 Harrow on the Hill tube station heading towards South the meeting. The White Cockade ......................... 5/11 Harrow drops passengers just below Garlands Lane – it’s AGENDA Neidpath Castle ............................... 22/9 about a 5 min ride. The same bus travels from South 1 Apologies. The Wild Geese .............................. 24/3 Harrow tube station also past Garlands Lane. (Note that 2 Approval of minutes of the 2006 AGM. The Reel of the 51st Division ....... 13/10 the fare is £2 now for any length of journey.) Taxis are 3 Business arising from the minutes. The Braes of Breadalbane ................ 21/7 available from the station. Ample car parking is available 4 Report on year's working of the Branch. -

NOTING the TRADITION an Oral History Project from the National Piping Centre

NOTING THE TRADITION An Oral History Project from the National Piping Centre Interviewee Professor Roddy Cannon Interviewer James Beaton Date of Interview 30 th November 2012 This interview is copyright of the National Piping Centre Please refer to the Noting the Tradition Project Manager at the National Piping Centre, prior to any broadcast of or publication from this document. Project Manager Noting The Tradition The National Piping Centre 30-34 McPhater Street Glasgow G4 0HW [email protected] Copyright, The National Piping Centre 2012 This is James Beaton for ‘Noting the Tradition.’ I’m here in the National Piping Centre with Professor Roddy Cannon, piper, piping historian and researcher, and also professionally a scientist. It’s St Andrew’s Day 2012 and we’re going to be speaking really about Roddy’s life and times in piping. Roddy, good morning and welcome. Good morning. Good morning. It’s always good to be back. Well, it’s nice to see you here and it’s nice to have you back. I come here on averageabout once a year these days. I give a number of classes and I talk to your students and I talk to the staff and I talk to you and it’s wonderful. Well, it’s nice to have you here. The thing that strikes me very much about your classes is that they’re so different from one year to the next. Some sit quietly and listen, some of them join the debate vigorously, and very occasionally I get confuted by counter arguments and that’s what I like best. -

Download PDF 8.01 MB

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2008 Imagining Scotland in Music: Place, Audience, and Attraction Paul F. Moulton Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC IMAGINING SCOTLAND IN MUSIC: PLACE, AUDIENCE, AND ATTRACTION By Paul F. Moulton A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2008 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Paul F. Moulton defended on 15 September, 2008. _____________________________ Douglass Seaton Professor Directing Dissertation _____________________________ Eric C. Walker Outside Committee Member _____________________________ Denise Von Glahn Committee Member _____________________________ Michael B. Bakan Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To Alison iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In working on this project I have greatly benefitted from the valuable criticisms, suggestions, and encouragement of my dissertation committee. Douglass Seaton has served as an amazing advisor, spending many hours thoroughly reading and editing in a way that has shown his genuine desire to improve my skills as a scholar and to improve the final document. Denise Von Glahn, Michael Bakan, and Eric Walker have also asked pointed questions and made comments that have helped shape my thoughts and writing. Less visible in this document has been the constant support of my wife Alison. She has patiently supported me in my work that has taken us across the country. She has also been my best motivator, encouraging me to finish this work in a timely manner, and has been my devoted editor, whose sound judgement I have come to rely on. -

Family Genealogy SURNAME INDEX to Date 12312015 A

Family Genealogy SURNAME INDEX to date 12312015 A A A) Misc, VF Abbey A) Abbey 1, VF Abbott A) Abbott 2, VF A) Abbott, Benj. & Augustine 1, VF W) Woodruff Genealogy (Abbott), HC* Abell A) Abell 1, VF Acker C) Descendants of Henry C. Clark (Acker), SC* Adair A) Ancestral History of Thelma D. Adair (Gander), HC Adams A) Adams 1, VF A) Adams, Abner, Zerviah 3, VF A) Adams and Griswold (Riggins), HC A) Adams Family (Adams), HC* A) Adams, Frank 2, VF H) Early Connecticut Holcomb's in Ashtabula Co., Trumbull Co., OH and PA (Holcomb), HC* R) RootAdamsMcDonaldHotling; RootHallamAtwaterGuest Genealogy (Dubach), SC W) Wright Genealogy, Moses Wright (Adams), SC Addicott A) Addicott, Beer 1, VF A) Addicott, Hersel 2, VF Addicott, James Henry Early Settler 1850, An/Cert #078, An/Cert #079 Addington Grantham & Skinner Genealogy MFM #1513336, Mfm Btm Drw Grantham & Skinner Genealogy MFM #1513337, Mfm Btm Drw Addison S) Peter Simpkins Family Genealogy (Simpkins), HC* Adset A) Adset 1, VF Aho A) Aho 1, VF G) Desendants of Casper Goodiel (Aho), SC* Aiken A) Aiken 1, VF L) Linkswilers of Louisiana (Martin), HC S) Seegar/Sager and Delp Genealogy (Williams), SC Ainger A) Ainger 1, VF Akeley A) Akeley 1, VF 1 Family Genealogy SURNAME INDEX to date 12312015 Alanko Berry, Gloucester Richard Heritage 1908, An/Cert #105 Brainard, David Pioneer 1820, An/Cert #109 Iloranta, Heikki Nestori Heritage 1919, An/Cert #106 I) The Iloranta and Soukka Families in America (Alanko), SC K) Klingman Family History (Alanko), SC* Albert A) Albert 1, VF Alden A) Alden, David 1, VF Alderman A) Alderman 1, VF A) Alderman 2, VF A) Alderman 3, VF A) Aldermans in America (Parker), SC A) Descendants of William Alderman. -

Contemporary Folk Dance Fusion Using Folk Dance in Secondary Schools

Unlocking hidden treasures of England’s cultural heritage Explore | Discover | Take Part Contemporary Folk Dance Fusion Using folk dance in secondary schools By Kerry Fletcher, Katie Howson and Paul Scourfield Unlocking hidden treasures of England’s cultural heritage Explore | Discover | Take Part The Full English The Full English was a unique nationwide project unlocking hidden treasures of England’s cultural heritage by making over 58,000 original source documents from 12 major folk collectors available to the world via a ground-breaking nationwide digital archive and learning project. The project was led by the English Folk Dance and Song Society (EFDSS), funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund and in partnership with other cultural partners across England. The Full English digital archive (www.vwml.org) continues to provide access to thousands of records detailing traditional folk songs, music, dances, customs and traditions that were collected from across the country. Some of these are known widely, others have lain dormant in notebooks and files within archives for decades. The Full English learning programme worked across the country in 19 different schools including primary, secondary and special educational needs settings. It also worked with a range of cultural partners across England, organising community, family and adult learning events. Supported by the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund, the National Folk Music Fund and The Folklore Society. Produced by the English Folk Dance and Song Society (EFDSS), June 2014 Written by: Kerry Fletcher, Katie Howson and Paul Schofield Edited by: Frances Watt Copyright © English Folk Dance and Song Society, Kerry Fletcher, Katie Howson and Paul Schofield, 2014 Permission is granted to make copies of this material for non-commercial educational purposes. -

Spring 2015 Vol. 44, No. 1 Table of Contents

Spring 2015 Vol. 44, No. 1 Table of Contents 4 President’s Message Music 5 Editorial 33 Jimmy Tweedie’s Sealegs 6 Letters to the Editor 43 Report for the Reviews Executive Secretary 34 Review of Gibson Pipe Chanter Spring 2015 35 The Campbell Vol. 44, No. 1 Basics Tunable Chanter 9 Snare Basics: Snare FAQ THE VOICE is the official publication of the Eastern United 11 Bass & Tenor Basics: Semiquavers States Pipe Band Association. Writing a Basic Tenor Score 35 The Making of the 13 Piping Basics: “Piob-ogetics” Casco Bay Contest John Bottomley 37 Pittsburgh Piping EDITOR [email protected] Features Society Reborn 15 Interview Shawn Hall 17 Bands, Games Come Together Branch Notes ART DIRECTOR 19 Willie Wows ‘Em 39 Southwest Branch [email protected] 21 The Last Happy Days – 39 Metro Branch Editorial Inquiries/Letters the Great Highland Bagpipe 40 Ohio Valley Branch THE VOICE in JFK’s Camelot 41 Northeast Branch [email protected] ADVERTISING INQUIRIES John Bottomley [email protected] THE VOICE welcomes submissions, news items, and ON THE COVER: photographs. Please send your Derek Midgley captured the joy submissions to the email above. of early St. Patrick’s parades in the northeast with this photo of Rich Visit the EUSPBA online at www.euspba.org Harvey’s pipe at the Belmar NJ event. ©2014 Eastern United States Pipe Band EUSPBA MEMBERS receive a subscription to THE VOICE paid for, in part, Association. All rights reserved. No part of this magazine may be reproduced or transmitted by their dues ($8 per member is designated for THE VOICE). -

Hornpipes and Disordered Dancing in the Late Lancashire Witches: a Reel Crux?

Early Theatre 16.1 (2013), 139–49 doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.12745/et.16.1.8 Note Brett D. Hirsch Hornpipes and Disordered Dancing in The Late Lancashire Witches: A Reel Crux? A memorable scene in act 3 of Thomas Heywood and Richard Brome’s The Late Lancashire Witches (first performed and published 1634) plays out the bewitching of a wedding party and the comedy that ensues. As the party- goers ‘beginne to daunce’ to ‘Selengers round’, the musicians instead ‘play another tune’ and ‘then fall into many’ (F4r).1 With both diabolical interven- tion (‘the Divell ride o’ your Fiddlestickes’) and alcoholic excess (‘drunken rogues’) suspected as causes of the confusion, Doughty instructs the musi- cians to ‘begin againe soberly’ with another tune, ‘The Beginning of the World’, but the result is more chaos, with ‘Every one [playing] a seuerall tune’ at once (F4r). The music then suddenly ceases altogether, despite the fiddlers claiming that they play ‘as loud as [they] can possibly’, before smashing their instruments in frustration (F4v). With neither fiddles nor any doubt left that witchcraft is to blame, Whet- stone calls in a piper as a substitute since it is well known that ‘no Witchcraft can take hold of a Lancashire Bag-pipe, for itselfe is able to charme the Divell’ (F4v). Instructed to play ‘a lusty Horne-pipe’, the piper plays with ‘all [join- ing] into the daunce’, both ‘young and old’ (G1r). The stage directions call for the bride and bridegroom, Lawrence and Parnell, to ‘reele in the daunce’ (G1r). At the end of the dance, which concludes the scene, the piper vanishes ‘no bodie knowes how’ along with Moll Spencer, one of the dancers who, unbeknownst to the rest of the party, is the witch responsible (G1r). -

Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle Music

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection Undergraduate Scholarship 3-1995 Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle Music Matthew S. Emmick Butler University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ugtheses Part of the Ethnomusicology Commons, and the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Emmick, Matthew S., "Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle Music" (1995). Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection. 21. https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ugtheses/21 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUTLER UNIVERSITY HONORS PROGRAM Honors Thesis Certification Matthew S. Emmick Applicant (Name as It Is to appear on dtplomo) Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle M'-Isic Thesis title _ May, 1995 lnter'lded date of commencemenf _ Read and approved by: ' -4~, <~ /~.~~ Thesis adviser(s)/ /,J _ 3-,;13- [.> Date / / - ( /'--/----- --",,-..- Commltte~ ;'h~"'h=j.R C~.16b Honors t-,\- t'- ~/ Flrst~ ~ Date Second Reader Date Accepied and certified: JU).adr/tJ, _ 2111c<vt) Director DiJe For Honors Program use: Level of Honors conferred: University Magna Cum Laude Departmental Honors in Music and High Honors in Spanish Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle Music A Thesis Presented to the Departmt!nt of Music Jordan College of Fine Arts and The Committee on Honors Butler University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation Honors Matthew S. Emmick March, 24, 1995 -l _ -- -"-".,---. -

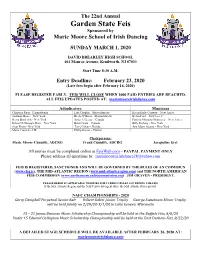

2020 Syllabus

The 22nd Annual Garden State Feis Sponsored by Marie Moore School of Irish Dancing SUNDAY MARCH 1, 2020 DAVID BREARLEY HIGH SCHOOL 401 Monroe Avenue, Kenilworth, NJ 07033 Start Time 8:30 A.M. Entry Deadline: February 23, 2020 (Late fees begin after February 16, 2020) PLEASE REGISTER EARLY. FEIS WILL CLOSE WHEN 1000 PAID ENTRIES ARE REACHED. ALL FEIS UPDATES POSTED AT: mariemooreirishdance.com Adjudicators Musicians Christina Ryan - Pennsylvania Lisa Chaplin – Massachusetts Karen Early-Conway – New Jersey Siobhan Moore - New York Breda O’Brien – Massachusetts Kevin Ford – New Jersey Kerry Broderick - New York Jackie O’Leary – Canada Patricia Moriarty-Morrissey – New Jersey Eileen McDonagh-Morr – New York Brian Grant – Canada Billy Furlong - New York Sean Flynn - New York Terry Gillan – Florida Ann Marie Acosta – New York Marie Connell – UK Philip Owens – Florida Chairpersons: Marie Moore-Cunniffe, ADCRG Frank Cunniffe, ADCRG Jacqueline Erel All entries must be completed online at FeisWeb.com – PAYPAL PAYMENT ONLY Please address all questions to: [email protected] FEIS IS REGISTERED, SANCTIONED AND WILL BE GOVERNED BY THE RULES OF AN COIMISIUN (www.clrg.ie), THE MID-ATLANTIC REGION (www.mid-atlanticregion.com) and THE NORTH AMERICAN FEIS COMMISSION (www.northamericanfeiscommission.org) JIM GRAVEN - PRESIDENT. PLEASE REFER TO APPLICABLE WEBSITES FOR CURRENT RULES GOVERNING THE FEIS If the Mid-Atlantic Region and the NAFC have divergent rules, the Mid-Atlantic Rules prevail. NAFC CHAMPIONSHIPS - 2020 Gerry Campbell Perpetual