Looking Backwards: How to Be a South African University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Western Cape Education Department

WESTERN CAPE EDUCATION DEPARTMENT CRITERIA FOR THE NATIONAL SENIOR CERTIFICATE (NSC) AWARDS FOR 2011 AWARDS TO SCHOOLS CATEGORY 1 - EXCELLENCE IN ACADEMIC PERFORMANCE In this category, awards are made to the top twenty schools in the province (including independent schools) that have achieved excellence in academic results in 2011, based on the following criteria: (a) Consistency in number of grade 12 candidates over a period of 3 years (at least 90%) of previous years (b) an overall pass rate of at least 95% in 2011 (c) % of candidates with access to Bachelor’s degree (d) % of candidates with Mathematics passes Each school will receive an award of R15 000 for the purchase of teaching and learning support material. CATEGORY 1: EXCELLENCE IN ACADEMIC PERFORMANCE No SCHOOL NAME 1. Rustenburg High School for Girls’ 2. Herschel Girls School 3. Diocesan College 4. Herzlia High School 5. Rondebosch Boys’ High School 6. Westerford High School 7. Hoër Meisieskool Bloemhof 8. South African College High School 9. Centre of Science and Technology 10. Paul Roos Gimnasium 11. York High School 12. Stellenberg High School 13. Wynberg Boys’ High School 14. Paarl Gimnasium 15. The Settlers High School 16. Hoër Meisieskool La Rochelle 17. Hoërskool Durbanville 18. Hoërskool Vredendal 19. Stellenbosch High School 20. Hoërskool Overberg 21. South Peninsula High School 22. Norman Henshilwood High School 2 CATEGORY 2 - MOST IMPROVED SCHOOLS Category 2a: Most improved Public Schools Awards will be made to schools that have shown the greatest improvement in the numbers that pass over the period 2009-2011. Improvement is measured in terms of the numbers passing. -

6318 SUPPLEMENT to the LONDON GAZETTE, 5 JUNE, 1920. to Be Companions of the Said Most Eminent Percy Armytage, Esq., M.V.O

6318 SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 5 JUNE, 1920. To be Companions of the said Most Eminent Percy Armytage, Esq., M.V.O. Order:— LieutenantX^lonel John Mackenzie RJogan, M.V.O. Charles Turner Allen, Esq., Cooper, Allen <fe. (Dated 30th March, 1920.) Co., Cawnpore, United Provinces. Lieutenant-Colonel1 Chetwynd Rokeby Alfred To be Member of the Fourth Class. Bond, C.B.E., late Indian Staff Corps. Major George Gooding. Charles William Egerton Cotton, Esq., Indian 'Civil Service, Collector of Customs, Calcutta. William Patrick Cowie, Esq., Indian Civil Ser- vice, Private Secretary to the Governor of CENTRAL CHANCERY OF THE ORDERS Bombay. Major Frederick Wernham Gerrard, Deputy OF KNIGHTHOOD. Commissioner of Police, Basrah, Mesopo- St. James's Palace, S.W. 1, tamia. 5th June,, 1920. Khan Bahadur Muhammad Habibulla Sahib Bahadur, Ex-Member of the Executive The KING has been graciously pleased, on Council of Madras. the occasion of His Majesty's Birthday, to Percy Harrison, Esq., Indian Civil Service, give orders for the following promotions in, Junior Member, Board of Revenue, United and appointments to, the Most Excellent Provinces. Order of the British Empire:—• Major Francis Henry Humphry s, Indian To be Knights Ground Cross of the Civil Army, Political Agent, Khyber, North-West Division of the said Most Excellent Frontier Province. Order:— Claud Mackenzie Hutchinson, Esq., Imperial Agricultural Bacteriologist. Sir Percy Elly Bates, Bart. Cowasji Jehangir, Junior, Esq., O.B.E., Presi- Voluntary services to the Ministry of dent, Bombay Municipality. .Shipping for five years. Charles Burdett La Touche, Esq., Manager, Sir John Lome MacLeod, LL.D., D.L. -

National Senior Certificate (NSC) Awards for 2017

National Senior Certificate (NSC) Awards For 2017 Awards to learners Learners Will Receive Awards For Excellence In Subject Performance, Excellence Despite Barriers To Learning, Special Ministerial Awards And For The Top 50 Positions In The Province. All Learners Will Receive A Monetary Award And A Certificate. Category : Learner Subject Awards In This Category, One Award Is Handed To The Candidate With The Highest Mark In The Designated Subjects. Each Learner Will Receive R 6 000 And A Certificate. Subject Description Name Centre Name Final Mark Accounting Kiran Rashid Abbas Herschel Girls School 300 Accounting Rita Elise Van Der Walt Hoër Meisieskool Bloemhof 300 Accounting Philip Visage Hugenote Hoërskool 300 Afrikaans Home Language Anri Matthee Hoërskool Overberg 297.8 Computer Applications Technology Christelle Herbst York High School 293.9 English Home Language Christopher Aubin Bishops Diocesan College 291.8 Engineering Graphics and Design Erin Michael Solomon Rondebosch Boys' High School 298.9 Nathan Matthew Wynberg Boys' High School 298.5 Information Technology Wylie Mathematics Erin Michael Solomon Rondebosch Boys' High School 299.7 Physical Sciences Tererai Muchabaiwa Malibu High School 300 Physical Sciences Erin Michael Solomon Rondebosch Boys' High School 300 Physical Sciences Matthys Louis Carstens Hoërskool Durbanville 300 Likhona Nosiphe Centre of Science & Technology 269.6 Isixhosa Home Language Qazisa Category: Excellence Despite Barriers to Learning In This Category, Learners Will Receive R10 000 And A Certificate. This Is Awarded To A Maximum Of Two Candidates With Special Education Needs Who Obtained The Highest Marks In Their Best Six Subjects That Fulfil The Requirements For The Award Of A National Senior Certificate. -

Former Fellows Biographical Index Part

Former Fellows of The Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783 – 2002 Biographical Index Part Two ISBN 0 902198 84 X Published July 2006 © The Royal Society of Edinburgh 22-26 George Street, Edinburgh, EH2 2PQ BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX OF FORMER FELLOWS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH 1783 – 2002 PART II K-Z C D Waterston and A Macmillan Shearer This is a print-out of the biographical index of over 4000 former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh as held on the Society’s computer system in October 2005. It lists former Fellows from the foundation of the Society in 1783 to October 2002. Most are deceased Fellows up to and including the list given in the RSE Directory 2003 (Session 2002-3) but some former Fellows who left the Society by resignation or were removed from the roll are still living. HISTORY OF THE PROJECT Information on the Fellowship has been kept by the Society in many ways – unpublished sources include Council and Committee Minutes, Card Indices, and correspondence; published sources such as Transactions, Proceedings, Year Books, Billets, Candidates Lists, etc. All have been examined by the compilers, who have found the Minutes, particularly Committee Minutes, to be of variable quality, and it is to be regretted that the Society’s holdings of published billets and candidates lists are incomplete. The late Professor Neil Campbell prepared from these sources a loose-leaf list of some 1500 Ordinary Fellows elected during the Society’s first hundred years. He listed name and forenames, title where applicable and national honours, profession or discipline, position held, some information on membership of the other societies, dates of birth, election to the Society and death or resignation from the Society and reference to a printed biography. -

Status and Respectability in the Cape Colony, 1750-1870: a Tragedy of Manners Robert Ross Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521621224 - Status and Respectability in the Cape Colony, 1750-1870: A Tragedy of Manners Robert Ross Index More information Index Abdul Zagie 139 Banks, Sir Joseph 49 Abdurahman, Dr A. 173 Baptism 11, 29–32, 95 Abu Bakr Effendi 141 Barbier, Etienne 17 Adderley Street, Cape Town 24 Barker, Arthur 78 Adolf van der Caab 130 Barrow, John 27, 42, 43 African National Congress 85, 153, 176 Barry, Dr James 47, 85 African Political Organisation 173 ‘Bastard-Hottentots’ 14, 135 Afrikaans 58, 59, 68 ‘Bastards’ 32, 152 dialects of 60 Bastards, baptised 32, 99 Albany 7, 50, 63, 64, 75, 78, 79, 135 Batavia 9–12, 15, 19, 21, 28, 33, 36, 80, 101, Alcohol 137 103, 108, 132, 141, 142 Alcohol addiction 138 Batavian Republic 7, 102, 104 Alexander van Banda 17 Bathurst 65, 66 Alexander, Captain James 154 Bathurst, Earl 55 Algoa Bay 60 Bayley, T. B. C. 168 Aliwal North 70 Beaufort West 173 Alleman, Rudolph Siegfried 23 Beck, Rev. J. J. 149 Angas, G. F. 86 Bedford 92 Anglicisation 53, 60 Beggars 158 Anti-Gallicanism 41 Bell, Charles Davidson 125, 127 Apprenticeship 8, 146, 149, 159 Bergh, Egbertus 102 see also Emancipation Bethelsdorp 112, 117, 118, 121, 124, 126, Arabic 143 150 Architecture Biddulph, T. J. 157 in Bo’kaap 81 Biggar, Alexander 135–6 British 81 Biko, Steve 153 Cape Dutch 80 Bird, Colonel Charles 55 Palladian 81 Bird, Lt-Col. Christopher 105 settler 79 Bird, W. W. 133 Arminius 104 Bisseux, Rev. Isaac 149 Army, British 7 Black Consciousness 153 Arson 17, 34 Bloemfontein 74–6, 85, 91 Artisans 175 Bo’kaap 81, 144 Auctions 42 Body language 2 Augsburg confession 103 Boers, Fiscaal W. -

Faculty of Humanities (Ceremony 3) Contents

FACULTY OF HUMANITIES (CEREMONY 3) CONTENTS Order of Proceedings 2 Mannenberg 3 The National Anthem 4 Distinctions in the Faculty of Humanities 5 Distinguished Teacher Award 6-7 Honorary Degree Recipient 8 Graduands (includes 23 December 2015 qualifiers) 9 Historical Sketch 18 Academic Dress 19-20 Mission Statement of the University of Cape Town 21 Donor Acknowledgements 22 Officers of the University 27 Alumni Welcome 28 1 FACULTY OF HUMANITIES (CEREMONY 3) ORDER OF PROCEEDINGS Academic Procession. (The congregation is requested to stand as the procession enters the hall) The Vice-Chancellor will constitute the congregation. The National Anthem. The University Statement of Dedication will be read by a representative of the SRC. Musical Item. Welcome by the Deputy Vice-Chancellor, Professor DP Visser. Professor Visser will present Dr Azila Talit Reisenberger for the Distinguished Teacher Award. Professor J Hambidge will present Dr Janette Deacon to the Vice-Chancellor for the award of an honorary degree. The graduands will be presented to the Vice-Chancellor by the Dean of Humanities, Professor S Buhlungu. The Vice-Chancellor will congratulate the new graduates. Professor Visser will make closing announcements and invite the congregation to stand. The Vice-Chancellor will dissolve the congregation. The procession, including the new graduates, will leave the hall. (The congregation is requested to remain standing until the procession has left the hall.) 2 MANNENBERG The musical piece for the processional march is Mannenberg, composed by Abdullah Ibrahim. Recorded with Basil ‘Manenberg’ Coetzee, Paul Michaels, Robbie Jansen, Morris Goldberg and Monty Weber, Mannenberg was released in June 1974. The piece was composed against the backdrop of the District Six forced removals. -

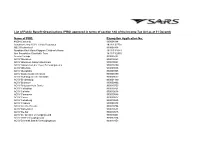

List of Section 18A Approved PBO's V1 0 7 Jan 04

List of Public Benefit Organisations (PBO) approved in terms of section 18A of the Income Tax Act as at 31 December 2003: Name of PBO: Exemption Application No: 46664 Concerts 930004984 Aandmymering ACVV Tehuis Bejaardes 18/11/13/2738 ABC Kleuterskool 930005938 Abraham Kriel Maria Kloppers Children's Home 18/11/13/1444 Abri Foundation Charitable Trust 18/11/13/2950 Access College 930000702 ACVV Aberdeen 930010293 ACVV Aberdeen Aalwyn Ouetehuis 930010021 ACVV Adcock/van der Vyver Behuisingskema 930010259 ACVV Albertina 930009888 ACVV Alexandra 930009955 ACVV Baakensvallei Sentrum 930006889 ACVV Bothasig Creche Dienstak 930009637 ACVV Bredasdorp 930004489 ACVV Britstown 930009496 ACVV Britstown Huis Daniel 930010753 ACVV Calitzdorp 930010761 ACVV Calvinia 930010018 ACVV Carnarvon 930010546 ACVV Ceres 930009817 ACVV Colesberg 930010535 ACVV Cradock 930009918 ACVV Creche Prieska 930010756 ACVV Danielskuil 930010531 ACVV De Aar 930010545 ACVV De Grendel Versorgingsoord 930010401 ACVV Delft Versorgingsoord 930007024 ACVV Dienstak Bambi Versorgingsoord 930010453 ACVV Disa Tehuis Tulbach 930010757 ACVV Dolly Vermaak 930010184 ACVV Dysseldorp 930009423 ACVV Elizabeth Roos Tehuis 930010596 ACVV Franshoek 930010755 ACVV George 930009501 ACVV Graaff Reinet 930009885 ACVV Graaff Reinet Huis van de Graaff 930009898 ACVV Grabouw 930009818 ACVV Haas Das Care Centre 930010559 ACVV Heidelberg 930009913 ACVV Hester Hablutsel Versorgingsoord Dienstak 930007027 ACVV Hoofbestuur Nauursediens vir Kinderbeskerming 930010166 ACVV Huis Spes Bona 930010772 ACVV -

Hermanus Magnetic Observatory: a Historical Perspective of Geomagnetism in Southern Africa

Hist. Geo Space Sci., 9, 125–131, 2018 https://doi.org/10.5194/hgss-9-125-2018 © Author(s) 2018. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Hermanus Magnetic Observatory: a historical perspective of geomagnetism in southern Africa Pieter B. Kotzé1,2 1South African National Space Agency, Space Science, Hermanus, South Africa 2Centre for Space Research, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa Correspondence: Pieter B. Kotzé ([email protected]) Received: 10 July 2018 – Revised: 6 August 2018 – Accepted: 13 August 2018 – Published: 24 August 2018 Abstract. In this paper a brief summary will be given about the historical development of geomagnetism as a science in southern Africa and particularly the role played by Hermanus Magnetic Observatory in this regard. From a very modest beginning in 1841 as a recording station at the Cape of Good Hope, Hermanus Magnetic Observatory is today part of the South African National Space Agency (SANSA), where its geomagnetic field data are extensively used in international research projects ranging from the physics of the geo-dynamo to studies of the near-Earth space environment. 1 Introduction Keetmanshoop enable studies of secular variation patterns over southern Africa and the influence of the South Atlantic The requirements of navigation during the era of explo- Magnetic Anomaly (e.g. Pavón-Carasco and De Santis, ration, rather than any scientific interest in geomagnetism, 2016) on the characteristics of the global geomagnetic prompted the recording of geomagnetic field components field. This is a region where the Earth’s magnetic field is at the Cape of Good Hope even before 1600 (Kotzé, 2007). -

Faculty of Commerce (Ceremony 5) Contents

FACULTY OF COMMERCE (CEREMONY 5) CONTENTS Order of Proceedings 2 Mannenberg 3 The National Anthem 4 Distinctions in the Faculty of Commerce 5 Distinguished Teacher Award 6-7 Graduands (includes 23 December 2015 qualifiers) 8 Origin of the Bachelor Degree 11 Values of the University 12-13 Academic Dress 14-15 Historical Sketch 16 Mission Statement of the University of Cape Town 17 Donor Acknowledgements 18 Officers of the University 23 Alumni Welcome 24 1 FACULTY OF COMMERCE (CEREMONY 5) ORDER OF PROCEEDINGS Academic Procession. (The congregation is requested to stand as the procession enters the hall) The Acting Vice-Chancellor, Professor DP Visser, will constitute the congregation. The National Anthem. The University Statement of Dedication will be read by a representative of the SRC. Musical Item. Welcome by the Deputy Vice-Chancellor, Professor F Petersen. Professor Petersen will present Jaqui Kew for the Distinguished Teacher Award. Address by Norman Arendse. The graduands and diplomates will be presented to the Acting Vice-Chancellor by the Deputy Dean of the Faculty of Commerce, Professor T Minter. The Acting Vice-Chancellor will congratulate the new graduates and diplomates. Professor Petersen will make closing announcements and invite the congregation to stand. The Acting Vice-Chancellor will dissolve the congregation. The procession, including the new graduates and diplomates, will leave the hall. (The congregation is requested to remain standing until the procession has left the hall.) 2 MANNENBERG The musical piece for the processional march is Mannenberg, composed by Abdullah Ibrahim. Recorded with Basil ‘Manenberg’ Coetzee, Paul Michaels, Robbie Jansen, Morris Goldberg and Monty Weber, Mannenberg was released in June 1974. -

District Directory 2003-2004

Handbook and Directory for Rotarians in District 9350 2017 – 2018 0 Rotary International President 2017-2018 Ian Riseley Ian H. S. Riseley is a chartered accountant and principal of Ian Riseley and Co., a firm he established in 1976. Prior to starting his own firm, he worked in the audit and management consulting divisions of large accounting firms and corporations. A Rotarian in the Rotary Club of Sandringham, Victoria, Australia since 1978, Ian has served Rotary as treasurer, director, trustee, RI Board Executive Committee member, task force member, committee member and chair, and district governor. Ian Riseley has been a member of the boards of both a private and a public school, a member of the Community Advisory Group for the City of Sandringham, and president of Beaumaris Sea Scouts Group. His honors include the AusAID Peacebuilder Award from the Australian government in 2002 in recognition of his work in East Timor, the Medal of the Order of Australia for services to the Australian community in 2006, and the Regional Service Award for a Polio-Free World from The Rotary Foundation. Ian and his wife, Juliet, a past district governor, are Multiple Paul Harris Fellows, Major Donors, and Bequest Society members. They have two children and four grandchildren. Ian believes that meaningful partnerships with corporations and other organizations are crucial to Rotary’s future. “We have the programs and personnel and others have available resources. Doing good in the world is everyone’s goal. We must learn from the experience of the polio eradication program to maximize our public awareness exposure for future partnerships. -

They Were South Africans.Pdf

1 05 028 THEY WERE SOUTH AFRICANS By John Bond CAPE TOWN OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON NEW YORK 4 Oxford University Press, Amen House, London, E.G. GLASGOW NEW YORK TORONTO MELBOURNE WELLINGTON BOMBAY CALCUTTA MADRAS KARACHI CAPE TOWN IBADAN NAIROBI ACCRA SINGAPORE First published November 1956 Second impression May 1957 Third impression November 1957 $ PRINTED IN THE UNION OF SOUTH AFRICA BY THE RUSTICA PRESS, PTY., LTD., WYNBERG, CAPE To the friends and companions of my youth at Grey High School, Port Elizabeth, and Rhodes University, Grahams- town, ivho taught me what I know and cherish about the English-speaking South Africans, this book is affectionately dedicated. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This book would not have been possible without the help and kindness of many people, 'who may not entirely agree with the views it expresses. I am greatly indebted to Mr D. H. Ollemans and the Argus Printing and Publishing Company, of which he is managing director, for granting me the generous allocation of leave without which it could never have been completed. At a critical moment Mr John Fotheringham's intervention proved decisive. And how can I forget the kindness with which Dr Killie Campbell gave me the freedom of her rich library of Africana at Durban for three months, and the helpfulness of her staff, especially Miss Mignon Herring. The Johannesburg Public Library gave me unstinted help, for which I am particularly indebted to Miss J. Ogilvie of the Africana section and her assistants. Professor A. Keppel Jones and Dr Edgar Brookes of Pietermaritzburg, Mr F. R. Paver of Hill- crest, and Mr T. -

Print This Article

THE MINUTE BOOK OF THE CAPE TOWN BRANCH OF THE CLASSICAL ASSOCIATION OF SOUTH AFRICA, 1927 - 1940 J Murray ( University of Cape Town) 1 This article surveys the contents of archival material found in the manuscript and archives section of the Special Collections of the University of Cape Town Libraries. In particular , it scrutinises the activities recorded in the Minute Book of the Cape Town Branch of the Classical Association of South Africa, 1927 - 1940. The details found in the Minute Book shed valuab le light on the teaching and research of classical antiquity in South Africa in the early part of the twentieth century, illuminating a lesser - known period of the history of the Classical Association of South Africa . Keywords : History of Classical Scholar ship; Classical e ducation; Classical Association of South Africa; South African h istory; i ntellectual h istory . In his record of the Classical Association of South Africa, 1908 - 1956, William Henderson noted that, ‘There was also a CASA during the years 192 7 - 1956, until now considered the “first”, but henceforth to be regarded as the “second ” . Very little has been written about and not much interest shown in this second association, probably because of lack of information, most of it buried in archives or lo st’. 2 More information is to be found in the Minute Book of the Cape Town Branch of the Classical Association of South Africa, covering the years 1927 to 1940, housed in the manuscripts and archives section of the Special Collections of the University of C ape Town Libraries (file BCS20).