Sea Pictures of a Convent Boarding School

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall 2020 the COMMITTEE

PRESENTATION DOORWAYS offering hospitality to the world Sisters of the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary and Associates | Dubuque, Iowa | Fall 2020 The COMMITTEE PUBLISHED QUARTERLY by the Sisters of the Presentation 2360 Carter Road Dubuque, Iowa 52001-2997 USA Phone: 563-588-2008 Fax: 563-588-4463 Email: [email protected] Sisters of the Presentation | Fall 2020 | Volume 64 • Number 3 Website: www.dbqpbvms.org DOORWAYS COMMITTEE Jane Buse-Miller, director of communications; Sister Carmen Hernandez; Sister Elena Hoye; Sister Joy Peterson; Cindy Pfiffner, associate A Look Inside co-director; Sister Francine Quillin; Marge CONTENTS Reidy; Karen Tuecke, partners in mission coordinator 4 Vote Humanity First The privilege of voting carries a serious moral responsibility that calls us to The cast votes that respect the dignity of all. This article focuses on our call to PUR POSE engagement as citizens, past and present obstacles to voting, remedies for The purpose of Presentation Doorways is enhancing voter turnout and proactive ways to influence outcomes. Pictured to further the mission of the Sisters of the to the right is Sister Richelle Friedman with the Honorable John Lewis. Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary and our associates by sharing the news 6 Conversion Takes Courage Engaging in radical hospitality by going outside our comfort zones into a and views of the congregation with our new culture or situation requires courage and bravery. This article provides benefactors, families and friends. Through us with helpful tools to become an anti-racist as we reflect and open our this publication, we hope to share the hearts to our own bias and tendencies. -

2019 | 2020 Annual Report

2019 | 2020 ANNUAL REPORT Saint Vincent de Paul Parish School is a Christ-centered community where each person is a valued child of God. We are dedicated to cultivating the mind and the heart. Completing the 2019-2020 School Year During a Pandemic n March 12, 2020, we left our beloved online learning from home. Utilizing Google Teacher Appreciation Week. They also school not knowing it would be our Classroom, Zoom, Flipgrid, and many other organized two drive-and-wave events for Olast day of the school year in which digital platforms, the faculty, administration, students and faculty to safely see one we were able to be together in classrooms, students, and families came together to another in person, one on May 8th, and a hallways, on our campus, and at our parish quickly adapt to this new and challenging second on the last day of school. We feel church. The unforeseen COVID-19 outbreak format. The faculty formulated virtual blessed that everyone was able to safely closed schools, churches, businesses, and solutions to keep school traditions alive complete the school year and overcome the kept families sheltered in their homes. St. including Third Grade State Reports, Spirit most unimaginable challenges to maintain Vincent de Paul Parish School continued the Week, Middle School Conduct Parties, Sixth the health and wellness of our community. school year by immediately implementing Grade Middle School Orientation, and 3RD GRADE STATE REPORTS SPIRIT WEEK TEACHER APPRECIATION ONLINE LEARNING DRIVE-AND-WAVE EVENTS: MAY 8, 2020 & LAST DAY OF SCHOOL 2019 All Saints Day 2019 Advent Service Let the Children Come to Me Presented to Fr. -

Summer 2010 Committeethe

PRESENTATION DO ORWAYS offering hospitality to the world Sisters of the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary and Associates | Dubuque, Iowa | Summer 2010 COMMITTEEThe PUBLISHED QUARTERLY by the Sisters of the Presentation 2360 Carter Road Dubuque, Iowa 52001-2997 USA Phone: 563-588-2008 Fax: 563-588-4463 Email: [email protected] Web site: www.dubuquepresentations.org PUBLISHER Jennifer Rausch, PBVM EDITOR/DESIGNER A Look Inside Jane Buse CONTENTS DOORWAYS COMMITTEE Sisters of the Presentation | Summer 2010 | Volume 53 • Number 2 Karla Berns, Associate; Diana Blong, PBVM; Elizabeth Guiliani, PBVM; Janice Hancock, PBVM; Joan Lickteig, PBVM; Carla Popes, PBVM; Leanne Welch, PBVM 4 Being a Visible Presence For the past seven years, Sister Francine Quillin has been The congregation is a member of Sisters United ministering as pastoral associate for Resurrection Parish in News (SUN) of the Upper Mississippi Valley, Dubuque, Iowa. National Communicators Network for Women Religious and the American Advertising Federation of Dubuque. 6 Building Hope, Changing Lives Café Reconcile, a nonprofit lunch restaurant and culinary training program in New Orleans, provides at-risk youth with Your life skills, job skills and hands-on work experience in all aspects T H O U G H T S of the restaurant business. Sister Mary Lou Specha joined the staff in 2008. & COMMENTS We want your input. Please send or email 8 Gathering of Temporary Professed photos, stories and information about our The Dubuque Presentation sisters participate in opportunites sisters, associates, former members, family to get to know other men and women in religious life. and friends, or any ideas which relate to the aim of this publication. -

Harsh Winter Likely As Recession Bites by GILLIAN VINE Vouchers to Rise

THE MON T HLY MAGAZINE FOR T HE CA T HOLI C S OF T HE DUNE D IN DIO C ESE HE ABLE T MayT 2009 T Issue No 143 Singing for Mum … Five-year-old Ted Nelson (left) leads fellow pupils of St Joseph’s School, Balclutha, in singing You Are My Shepherd after the May 5 Mass at which his mother, Annie Nelson, was commissioned as principal of the school� Beside Ted is Tamara-Lee Rodwell� At the Mass, parish priest Fr Michael Hishon noted it was Good Shepherd Sunday and said a challenge to Mrs Nelson was “to be like the shepherd … and do her best to lead” the school� Fr Hishon spoke of Mrs Nelson’s love of and commitment to her calling and expressed his confidence that the roll, now standing at 53, would continue to rise under Mrs Nelson’s leadership� – Gillian Vine Harsh winter likely as recession bites By GILLIAN VINE vouchers to rise. demand will certainly be higher than ST VINCENT de Paul branches in the Dunedin area manager Ken Fahey last year,” he said. diocese are bracing themselves for also predicted a rise in requests for He attributed higher demand post- higher demand this winter as the assistance, saying: “Winter could be the Christmas to the tougher economic recession takes its toll. critical period.” climate, as overtime and even basic “I would expect it to get busier, In January and February, Dunedin’s St hours for workers were cut. Food bank especially with recent redundancies in Vincent de Paul food bank had recorded donations from Dunedin parishes were the town,” Oamaru St Vincent de Paul 25 per cent increases in demand on “solid” and he was “just so happy and shop manager Jeanette Verheyen said. -

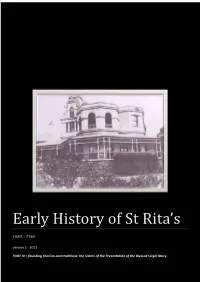

Early History of St Rita's

Early History of St Rita’s 1885 - 1960 Version 1 - 2013 PART III – founding charism and traditions: the Sisters of the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary. NANO NAGLE Nano Nagle (christened Honora) was born in 1718 of a long- standing Catholic family at Ballygriffin near Mallow in North Cork. Her home lay in the beautiful valley of the Blackwater backed by the Nagle Mountains to the south. Her father was Garret Nagle, a wealthy landowner in the area; her mother, Ann Mathews, was from an equally prominent family in Co. Tipperary. Like others of the old Catholic gentry, the Nagles had managed to hold on to most of their land and wealth during the era of the Penal Laws in the eighteenth century. Edmund Burke, the famous parliamentaria n and orator, who was a relative of Nano Nagle on his mother's side, and had spent his early years in Ballygriffin, described those laws in one trenchant sentence: "Their declared object was to reduce the Catholics in Ireland to a miserable populace, without property, without estimation, without education" The Penal Laws made it unlawful to open a Catholic school at home, and at the same time, forbade them to travel overseas for their education. Nano had to go to a hedge school for her primary education. While the "hedge school" label suggests the classes always took place outdoors next to a hedgerow, classes were sometimes held in a house or barn. A hedgerow is a line of closely spaced shrubs and tree species, planted and trained to form a barrier or to separate a road from adjoining fields or one field from another. -

Nano Nagle and the International Presentation Association

Nano Nagle and the International Presentation Association A reflection on the IPA story Kathleen Tynan, PBVM In a letter dated 17 July, 1769, Nano Nagle wrote, “For I can assure you my schools are beginning to be of service to a great many parts of the world – this [Cork] is a place of such trade ... If I could be of any service in saving souls in any part of the globe I would willingly do all in my power.” Nano’s contemplative spirit gave her a vision that extended beyond the winding lanes of Cork to encompass gospel service that was global. The seeds of the International Presentation Association are in this vision. The International Presentation Association story began in 1981 during an international meetings of congregation leaders in Rome. Several Presentation leaders were present. In breaks between sessions they met informally in a room in the Ergife Hotel. Nano’s words, “there is no greater happiness than to be in union,” resonated within the group and a desire to be more closely connected was born. There is no greater happiness than to be in union In 1984, the Australian Society hosted a national gathering to mark the 200th anniversary of Nano’s death. The Society leadership at the time included sisters who had been present in 1981. Invitations were extended to Presentation leaders from across the globe. A national gathering of 280 sisters from Society became international when seven leaders from the Conference and seven leaders from the Union attended. This experience convinced sisters that more could be done together than alone. -

The Life of Mary Aikenhead Part 2879.06 KB

A short synopsis of the life of Mother Mary Aikenhead Part Two Mary begins to focus on religious life Mary began to think seriously of devoting her life full-time and as a religious to helping the poor in their homes but for the present she felt obliged to help her ailing mother in the management of the household. The Ursuline and Presentation Sisters, whose convents were nearby, were bound to enclosure. Even in the whole of Ireland at this period there was no convent that allowed its members to move outside the enclosure. When Mary discussed this with Cecilia Lynch, Cecilia informed her that she herself was joining the Poor Clares in Harold’s Cross, Dublin. An unexpected, life-changing meeting Then on 30 November 1807, when Mary was 20 years of age, a providential meeting took place at the Ursuline convent in Cork. Mary met Anna Maria Ball of Dublin, a wealthy woman in her own right who was married to a rich Dublin merchant, John O’Brien. She had come to Cork for the religious profession of her sister, Cecilia. Accompanying her was another sister, Frances or Fanny, the future founder of the Loretto sisters. Mary Aikenhead found that she had met a kindred spirit in Anna Maria. Mary already knew from her friend, Cecilia Lynch that Anna Maria devoted a great deal of her time in Dublin to the care of the poor and afflicted. Before leaving Cork, Mrs. O’Brien invited Mary to spend some time with her in Dublin. The invitation was gladly accepted. -

Authentic Expression of Edmund Rice Christian Brother Education

226 Catholic Education/December 2007 AUTHENTIC EXPRESSION OF EDMUND RICE CHRISTIAN BROTHER EDUCATION RAYMOND J. VERCRUYSSE, C.F.C. University of San Francisco The Congregation of Christian Brothers (CFC), a religious community which continues to sponsor and staff Catholic high schools, began in Ireland with the vision of Edmund Rice. This article surveys biographical information about the founder and details ongoing discussions within the community directed toward preserving and growing Rice’s vision in contemporary Catholic schools. BACKGROUND n 1802, Edmund Rice directed the laying of the foundation stone for IMount Sion Monastery and School. After several previous attempts of instructing poor boys in Waterford, this was to be the first permanent home for the Congregation of Christian Brothers. Rice’s dream of founding a reli- gious community of brothers was becoming a reality with a school that would reach out to the poor, especially Catholic boys of Waterford, Ireland. Edmund Rice grew up in Callan, County Kilkenny. The Rice family was described as “a quiet, calm, business people who derived a good living from the land and were esteemed and respected” (Normoyle, 1976, p. 2). Some historians place the family farm in the Sunhill townland section of the coun- ty. The family farm was known as Westcourt. It was at Westcourt that Robert Rice and Margaret Tierney began a life together. However, “this life on the family farm was to be lived under the partial relaxation of the Penal Laws of 1782” (Normoyle, 1976, p. 3). This fact would impact the way the Rice family would practice their faith and limit their participation in the local Church. -

18Th February 2001

THE BALLINCOLLIG 6 PAGE EDITION PARISHIONER CHRIST OUR LIGHT ST. MARY & ST. JOHN INNISHMORE SUNDAY 18TH FEBRUARY 2001 STATION ROAD SEVENTH SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME Christians are required to answer hatred with goodness, curses with blessings and ill treatment with prayer. As descendants of Adam, this is difficutl but through the power of Christ and his Holy Spirit, we can succeed. I WONDER................. PRAYERS OF Some time ago I did an article in the ’Parishioner concerning the environment, and it brought some response and comment, hopefully it was to some effect. THE FAITHFUL This week I’d like to raise awareness on the B.S.E. crisis that is hitting our beef PRIEST industry at present. As I begin I wish to stress that the following is a personal My brothers and sisters, opinion based on my reading of the current scene as I see it. the Lord is compassion and love, Most of us are familiar with the unpleasant sight of the stumbling cow on our so we bring our prayers to God. T.V. screens and so we are told this is what a Mad Cow looks like. Thankfully I have never come across a cow like this one in the dealings that I had with READER animals and I hope that I never will. As most of you know I grew up on a farm For religious leaders and all who and so have a great love of animals, this being instilled into me since I was very preach God’s forgiveness, that they small. There is, I feel another side to animals other than one of the stumbling may receive the grace to practise it. -

Catholic Women Religious in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1850

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Sisterhood on the Frontier: Catholic Women Religious in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1850- 1925 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology by Jamila Jamison Sinlao Committee in charge: Professor Denise Bielby, Chair Professor Jon Cruz Professor Simonetta Falasca-Zamponi Professor John Mohr December 2018 The dissertation of Jamila Jamison Sinlao is approved. Jon Cruz Simonetta Falsca-Zamponi John Mohr Denise Bielby, Committee Chair December 2018 Sisterhood on the Frontier: Catholic Women Religious in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1850- 1925 Copyright © 2018 by Jamila Jamison Sinlao iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In so many ways, this dissertation is a labor of love, shaped by the formative years that I spent as a student at Mercy High School, Burlingame. There, the “Mercy spirit”—one of hospitality and generosity, resilience and faith—was illustrated by the many stories we heard about Catherine McAuley and Mary Baptist Russell. The questions that guide this project grew out of my Mercy experience, and so I would like to thank the many teachers, both lay and religious, who nurtured my interest in this fascinating slice of history. This project would not have been possible without the archivists who not only granted me the privilege to access their collections, but who inspired me with their passion, dedication, and deep historical knowledge. I am indebted to Chris Doan, former archivist for the Sisters of the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary; Sister Marilyn Gouailhardou, RSM, regional community archivist for the Sisters of Mercy Burlingame; Sister Margaret Ann Gainey, DC, archivist for the Daughters of Charity, Seton Provincialate; Kathy O’Connor, archivist for the Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur, California Province; and Sister Michaela O’Connor, SHF, archivist for the Sisters of the Holy Family. -

Bulletin 2Nd May 2021

CB All Hallows’ Five Dock Fifth Sunday of Easter | Year B | Sunday 2nd May Parish Mission A Message from Fr Joseph We, the people of this place, Dear Friends in Christ, every one of his disciples, as well as the live and celebrate a love of faith. Today’s second reading, from the first community of his followers. Those who hear We share this faith in a letter of John, gives us another his words are the new vine, the new People spirit of service, expression of the same message: “let us of God. The community will have life only in that creates a sense of God’s presence among us. love not in word or speech but indeed as much as it is fully connected to the source and truth.” One of the criteria by which of life, the true vine. All Hallows’ Parish we can determine if love is authentic is Maybe one of the questions might resonate Parish Priest: Fr Joseph Kolodziej in its relationship to the truth, and in the more with our prayer today: How are the M: 0412 085 189 coherence of our actions. In the Gospel, fruits of my labour connected to my Jesus offers what must have been a relationship with Christ? Am I resisting some Deacon: familiar image to explain what it means pruning that God is trying to do with me? Rev. Mr Constantine Rodrigues to live in his love, and how we can Where might I need to do some pruning in Parish Secretary: “measure” the love that gives us life. -

Presentation Sisters

FOUNDATIONS IN CATHOLIC EDUCATION Presentation Sisters After a short rest they boarded the SS Australind at Fremantle, where they spent three days getting tossed around on the stormy water before setting out on the last leg of the 24 hour trip to Geraldton. On arrival they assumed responsibility for the school that had been kept open for them by the Sisters of Mercy and commenced work the very next day. It was the beginning of a long, successful and continuing presence Presentation Convent in Geraldton – circa 1911 of Presentation Sisters in schools within the Geraldton Diocese. During the next 78 years, the following schools were opened: Geraldton 1891, Northampton 1899, Roebourne 1901, Greenough 1902, Lawlers 1903, Carnarvon 1906, Sandstone 1909, Goomalling 1912, Mullewa 1914, Mt Magnet 1915, Youanmi 1918, Wiluna 1933, Nanson 1939, Bluff Point 1940, Wonthella 1940, Tardun Iona music pupils – 1911 1941, Port Hedland 1942, Big Bell 1949, Wittenoom 1956, Beachlands 1963 and Rangeway 1969. Group of Presentation Sisters with Bishop J. O’Collins, Lancelin 1955, Rivervale 1956, Boyup Brook 1957, Corrigin 1959, centre front row, 1936 Extraordinary experiences Cloverdale, 1961, Dowerin 1962 and Karratha Primary 1978 and Secondary 1987. The beginning Their experience was extraordinary. They followed the mining towns, opening and closing schools wherever there was a need, even While the Sisters continued to work very hard, the smaller schools gradually closed due to a decline in the farming population, the In 2003, the Irish Newspaper The Sunday taking their convent and school by ‘jinker’ (a wheeled flat topped amalgamation of schools and the lack of Sisters to staff the schools.