The Cross Border Expansion of African Lfcis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Full Year 2020 Results Presentation to Investors and Analysts

FULL YEAR 2020 RESULTS PRESENTATION TO INVESTORS AND ANALYSTS Disclaimer The information presented herein is based on sources which Access Bank The information should not be interpreted as advice to customers on the Plc. (the “Bank”) regards dependable. This presentation may contain purchase or sale of specific financial instruments. Access Bank Plc. bears no forward looking statements. These statements concern or may affect future responsibility in any instance for loss which may result from reliance on the matters, such as the Bank’s economic results, business plans and information. strategies, and are based upon the current expectations of the directors. Access Bank Plc. holds copyright to the information, unless expressly They are subject to a number of risks and uncertainties that might cause indicated otherwise or this is self-evident from its nature. Written permission actual results and events to differ materially from the expectations from Access Bank Plc. is required to republish the information on Access expressed in or implied by such forward looking statements. Factors that Bank or to distribute or copy such information. This shall apply regardless of could cause or contribute to differences in current expectations include, but the purpose for which it is to be republished, copied or distributed. Access are not limited to, regulatory developments, competitive conditions, Bank Plc.'s customers may, however, retain the information for their private technological developments and general economic conditions. The Bank use. assumes no responsibility to update any of the forward looking statements contained in this presentation. Transactions with financial instruments by their very nature involve high risk. -

Ecobank Group Annual Report 2018 Building

BUILDING AFRICA’S FINANCIAL FUTURE ECOBANK GROUP ANNUAL REPORT 2018 BUILDING AFRICA’S FINANCIAL FUTURE ECOBANK GROUP ANNUAL REPORT 2018 ECOBANK GROUP ANNUAL REPORT CONTENTS 05 Performance Highlights 08 Ecobank is the leading Pan-African Banking Institution 09 Business Segments 10 Our Pan-African Footprint 15 Board and Management Reports 16 Group Chairman’s Statement 22 Group Chief Executive’s Review 32 Consumer Bank 36 Commercial Bank 40 Corporate and Investment Bank 45 Corporate Governance 46 Board of Directors 48 Directors’ Biographies 53 Directors’ Report 56 Group Executive Committee 58 Corporate Governance Report 78 Sustainability Report 94 People Report 101 Risk Management 141 Business and Financial Review 163 Financial Statements 164 Statement of Directors’ Responsibilities 165 Auditors’ Report 173 Consolidated Financial Statements 178 Notes to Consolidated Financial Statements 298 Five-year Summary Financials 299 Parent Company’s Financial Statements 305 Corporate Information 3 ECOBANK GROUP ANNUAL REPORT 3 PERFORMANCE HIGHLIGHTS 5 ECOBANK GROUP ANNUAL REPORT PERFORMANCE HIGHLIGHTS For the year ended 31 December (in millions of US dollars, except per share and ratio data) 2018 2017 Selected income statement data Operating income (net revenue) 1,825 1,831 Operating expenses 1,123 1,132 Operating profit before impairment losses & taxation 702 700 Impairment losses on financial assets 264 411 Profit before tax 436 288 Profit for the year 329 229 Profit attributable to ETI shareholders 262 179 Profit attributable per share ($): Basic -

Equipment Leasing in Africa Handbook of Regional Statistics 2017 Including an Overview of 10 Years of IFC Leasing Intervention in the Region

AFRICA LEASING FACILITY II Equipment Leasing in Africa Handbook of Regional Statistics 2017 Including an overview of 10 years of IFC leasing intervention in the region © 2017 INTERNATIONAL FINANCE CORPORATION 2121 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W., Washington, DC 20433 All rights reserved. First printing, March 2018. This document may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the written consent of the International Finance Corporation. This information, while based on sources that IFC considers to be reliable, is not guaranteed as to accuracy and does not purport to be complete. The conclusions and judgments contained in this handbook should not be attributed to, and do not necessarily represent the views of IFC, its partners, or the World Bank Group. IFC and the World Bank do not guarantee the accuracy of the data in this publication and accept no responsibility for any consequence of its use. Rights and Permissions Reference Section III. What is Leasing? and parts of Section IV. Value of Leasing in Emerging Economies are taken from IFC’s “Leasing in Development: Guidelines for Emerging Economies.” 2005, which draws upon: Halladay, Shawn D., and Sudhir P. Amembal. 1998. The Handbook of Equipment Leasing, Vol. I-II, P.R.E.P. Institute of America, Inc., New York, N.Y.: Available from Amembal, Deane & Associates. EQUIPMENT LEASING IN AFRICA: ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Acknowledgement This first edition of Equipment Leasing in Africa: A handbook of regional statistics, including an overview of 10 years of IFC leasing intervention in the region, is a collaborative efort between IFC’s Africa Leasing Facility team and the regional association of leasing practitioners, known as Africalease. -

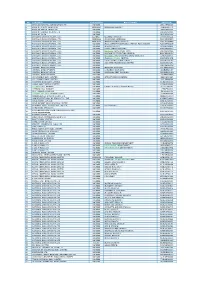

Bank Code Finder

No Institution City Heading Branch Name Swift Code 1 AFRICAN BANKING CORPORATION LTD NAIROBI ABCLKENAXXX 2 BANK OF AFRICA KENYA LTD MOMBASA (MOMBASA BRANCH) AFRIKENX002 3 BANK OF AFRICA KENYA LTD NAIROBI AFRIKENXXXX 4 BANK OF BARODA (KENYA) LTD NAIROBI BARBKENAXXX 5 BANK OF INDIA NAIROBI BKIDKENAXXX 6 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. ELDORET (ELDORET BRANCH) BARCKENXELD 7 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. MOMBASA (DIGO ROAD MOMBASA) BARCKENXMDR 8 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. MOMBASA (NKRUMAH ROAD BRANCH) BARCKENXMNR 9 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (BACK OFFICE PROCESSING CENTRE, BANK HOUSE) BARCKENXOCB 10 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (BARCLAYTRUST) BARCKENXBIS 11 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (CARD CENTRE NAIROBI) BARCKENXNCC 12 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (DEALERS DEPARTMENT H/O) BARCKENXDLR 13 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (NAIROBI DISTRIBUTION CENTRE) BARCKENXNDC 14 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (PAYMENTS AND INTERNATIONAL SERVICES) BARCKENXPIS 15 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (PLAZA BUSINESS CENTRE) BARCKENXNPB 16 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (TRADE PROCESSING CENTRE) BARCKENXTPC 17 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (VOUCHER PROCESSING CENTRE) BARCKENXVPC 18 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI BARCKENXXXX 19 CENTRAL BANK OF KENYA NAIROBI (BANKING DIVISION) CBKEKENXBKG 20 CENTRAL BANK OF KENYA NAIROBI (CURRENCY DIVISION) CBKEKENXCNY 21 CENTRAL BANK OF KENYA NAIROBI (NATIONAL DEBT DIVISION) CBKEKENXNDO 22 CENTRAL BANK OF KENYA NAIROBI CBKEKENXXXX 23 CFC STANBIC BANK LIMITED NAIROBI (STRUCTURED PAYMENTS) SBICKENXSSP 24 CFC STANBIC BANK LIMITED NAIROBI SBICKENXXXX 25 CHARTERHOUSE BANK LIMITED NAIROBI CHBLKENXXXX 26 CHASE BANK (KENYA) LIMITED NAIROBI CKENKENAXXX 27 CITIBANK N.A. NAIROBI NAIROBI (TRADE SERVICES DEPARTMENT) CITIKENATRD 28 CITIBANK N.A. -

Africa Digest Vol. 2019-04

Vol. 2019 – 04 Contents 1. Trends on China in Africa ................................................................................ 2 2. Financial Services in Africa ............................................................................. 6 3. Western Companies in Africa .......................................................................... 9 4. Fintech and Mobile Money ............................................................................ 12 5. Linking Africa to the World ............................................................................. 16 1 Vol. 2019 – 04 1. Trends on China in Africa INTRODUCTION China’s presence in Africa is the topic of many papers, articles and arguments. Over the past few years, the Chinese government and its private sector became major players on the continent in trade, investments, and support for African governments. AFRICA China has diversified its sources of energy to meet growing domestic demand. Three of its national oil companies (NOCs) increased their investment in Africa to secure oil supplies, which accounts for almost 30% of their combined international upstream capital spending (capex). Within the next five years, these NOCs are projected to become the fourth highest source of capex in Africa’s upstream sector, after global counterparts BP, Shell and Eni SpA. They will invest US$15 billion in Africa, with two-thirds of their investment going to Nigeria, Angola, Uganda and Mozambique.1 The opportunity for exports from Africa to China presents an interesting counterpoint to China’s investments in Africa. Some commentators suggest that China can narrow its trade surplus with African countries and help them develop more economic growth by importing more value-added products from Africa. China’s consumer market is the world’s largest, and is growing at 16% compared to a US consumer market that is growing at only 2%. Unsurprisingly, private sector companies from Africa are increasingly interested in entering the Chinese market. -

Personal Banking

2019 ANNUAL REPORT & ACCOUNTS ACCESS BANK PLC 1 access more 2019 ANNUAL REPORT & ACCOUNTS 2 ACCESS BANK PLC MERGING CAPABILITIES FOR SUSTAINABLE GROWTH 2019 ANNUAL REPORT & ACCOUNTS ACCESS BANK PLC 3 1 OVERVIEWS .............08 10 • Business and Financial Highlights 12 • Locations and Offices 14 • Chairman’s Statement CONTENTS// 18 • Chief Executive Officer's Review 2 BUSINESS REVIEW.............22 24 • Corporate Philosophy 25 • Reports of the External Consultant 26 • Commercial Banking 30 • Business Banking 34 • Personal Banking 40 • Corporate and Investment Banking 44 • Transaction Services, Settlement Banking and IT 46 • Digital Banking 50 • Our People, Culture and Diversity 54 • Sustainability Report 74 • Risk Management Report 3 GOVERNANCE .............92 94 • The Board 106 • Directors, Officers & Professional Advisors 107 • Management Team 108 • Directors’ Report 116 • Corporate Governance Report 136 • Statement of Directors’ Responsibilities 138 • Report of the Statutory Audit Committee 140 • Customers’ Complaints & Feedback 144 • Whistleblowing Report 4 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS ............148 150 • Independent Auditor’s Report 156 • Consolidated Statement of Comprehensive Income 157 • Consolidated Statement of Financial Position 158 • Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 162 • Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 164 • Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements 203 • Other National Disclosures SHAREHOLDER 5 INFORMATION ............404 406 • Shareholder Engagement 408 • Notice of Annual General Meeting 412 • Explanatory -

Registered Attendees

Registered Attendees Company Name Job Title Country/Region 1996 Graduate Trainee (Aquaculturist) Zambia 1Life MI Manager South Africa 27four Executive South Africa Sales & Marketing: Microsoft 28twelve consulting Technologies United States 2degrees ETL Developer New Zealand SaaS (Software as a Service) 2U Adminstrator South Africa 4 POINT ZERO INVEST HOLDINGS PROJECT MANAGER South Africa 4GIS Chief Data Scientist South Africa Lead - Product Development - Data 4Sight Enablement, BI & Analytics South Africa 4Teck IT Software Developer Botswana 4Teck IT (PTY) LTD Information Technology Consultant Botswana 4TeckIT (pty) Ltd Director of Operations Botswana 8110195216089 System and Data South Africa Analyst Customer Value 9Mobile Management & BI Nigeria Analyst, Customer Value 9mobile Management Nigeria 9mobile Nigeria (formerly Etisalat Specialist, Product Research & Nigeria). Marketing. Nigeria Head of marketing and A and A utilities limited communications Nigeria A3 Remote Monitoring Technologies Research Intern India AAA Consult Analyst Nigeria Aaitt Holdings pvt ltd Business Administrator South Africa Aarix (Pty) Ltd Managing Director South Africa AB Microfinance Bank Business Data Analyst Nigeria ABA DBA Egypt Abc Data Analyst Vietnam ABEO International SAP Consultant Vietnam Ab-inbev Senior Data Analyst South Africa Solution Architect & CTO (Data & ABLNY Technologies AI Products) Turkey Senior Development Engineer - Big ABN AMRO Bank N.V. Data South Africa ABna Conseils Data/Analytics Lead Architect Canada ABS Senior SAP Business One -

Cash Country Service Listing April 2014

® WorldLink Payment Services Cash Country Service Listing April 2014 WorldLink® Cash payments is currently offered through Western Union and is thus required to follow the requirements and regulations of within the destination country of your beneficiary. Failure to meet those requirements will result in the payment being rejected. The information provided in the WorldLink Cash Country Service Listing includes updates sent to Western Union prior to:April 2014. The material contained in this Cash Country Service Listing is for informational purposes only, and is provided solely as a courtesy by WorldLink. Although WorldLink believes this information to be reliable, WorldLink makes no representation or warranty with respect to its accuracy or completeness. The information in this Cash Country Service Listing does not constitute a recommendation to take or refrain from taking any action, and WorldLink is not providing any tax, legal or other advice. Citigroup and its affiliates accept no liability whatsoever for any use of this material or any action taken based on or arising from anything contained herein. The information in this Cash Country Service Listing is subject to change at any time according to changes in local law. WorldLink is not obligated to inform you of changes to local law. Citibank Europe plc (“Citibank Europe”) may, at its discretion, reasonably modify or amend this Cash Country Service Listing from time to time, which modification or amendment will become binding when your organization receives a copy of it. These materials are confidential and proprietary to Citigroup or its affiliates and no part of these materials should be reproduced, published in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopy or any information storage or retrieval system nor should the materials be disclosed to third parties without our express written authorization. -

FY-2020-Results-Announcement.Pdf

LAGOS, NIGERIA 1 April 2021 Group Audited Results for the Full Year ended 31 December 2020 Access Bank delivered solid and resilient top-line figures despite a challenging economic and regulatory landscape. This is an attestation to our long history of resilience, scale, dedicated people and sustainable business model. Our resilient business model ensured that the Group adapted to accommodate the resultant macro-economic downturn and headwinds of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Group recorded gross earnings of ₦764.7bn (+15% y/y), arising from a 112% y/y growth in non- interest income to ₦275.5bn, which is testimonial to the effectiveness of our strategy and capacity to generate sustainable revenue. Profit Before Tax stood at ₦125.9bn despite the high cost of operating the enlarged franchise and the increase in net impairment charge of near ₦43bn arising principally (~50% of net impairment) from a Structured Trade Finance (“STF”) portfolio in the Access Bank UK. The STF impairment is one-off/COVID related and recoverable over the next 12-18 months against insurance cover from world class insurers. We also recorded consistent growth in our retail banking business, leading to a 5.8mn growth in customer sign-on during the year via our financial inclusion drive and retail revenue of ₦177.2bn (FY 2019: ₦107.8bn). Customer deposits grew by 31% to ₦5.59trn in Dec 2020 (Dec 2019: ₦4.26trn) with savings account deposits of ₦1.31trn. Similarly, net loans and advances grew by 18% to ₦3.61trn (Dec 2019: ₦3.06trn). Our asset quality also continued to improve as guided to 4.3% (Dec. -

ACCESS BANK PLC DECEMBER 2009 FULL YEAR and FIRST QUARTER 2010 RESULTS PRESENTATION Outline

ACCESS BANK PLC DECEMBER 2009 FULL YEAR AND FIRST QUARTER 2010 RESULTS PRESENTATION Outline About Access Bank Operating Environment 9 Months (December 2009) Performance Review Q1 March 2010 Performance review Ongoing Strategic Initiatives 2 December 31, 2009 2009 FULL YEAR RESULTS PRESENTATION Access Group – Fact Sheet United KingdomUnited Parent Company : Access Bank Plc registered in Nigeria as Kingdom a Universal bank and commenced operations Access Bank Group in May 1989 OmniFinance Bank Access Bank 75% 88% No of Employees : Over 2000 Professional staff Gambia Cote d’Ivoire Access Bank Access Bank 85% 75% Listing : Ordinary Shares & 3 years Convertible Bond Sierra Leone Zambia listed on NSE; Several International GDR The Access Bank Access Bank 100% 100% Holders. Paper traded OTC in London Rwanda UK FinBank 79% 100% Access Bank (RD Auditors : KPMG Professional Services Burundi Congo) Access Homes & 100% 75% Access Bank Credit Rating : A- / B+/ BB/ BBB- Mortgage Ghana (GCR/S&P/Agusto/Fitch) United 100% Access Securities 75% Investments & Securities Partners : Focus Client Segments Institutional (& Public Sector) Awards & Recognitions : 2007 Award of Recognition for “Innovation in Middle Market Trade Structures” 2008 Award of Recognition for “Best Network Distributors & Professionals Banks” Key Industry Segments : Telecoms, Food & Beverages, Cements, Oil & Treasury Gas and Financial Institutions Cash Management Channels : 131 Business Offices Trade Finance 216 ATMs, 204 POS, Call Centre Cards & Payment Services 3 Non-Banking subsidiaries; 9 Banking subsidiaries Asset Mgt. & Custodial Services Capabilities Key Relationship Management Geographical Coverage : Africa and Europe Banking subsidiaries in all monetary zones in Africa December 31, 2009 3 2009 FULL YEAR RESULTS PRESENTATION Board & Management Expertise Our Management Team possesses the requisite skills and experience required to emerge as Winners in a challenging operating environment. -

Summary on Participants

SUMMARY ON PARTICIPANTS CENTRAL BANKS / BANQUES CENTRALES B Observers Final List page 64 SUMMARY ON PARTICIPANTS CENTRAL BANKS-AFRICAN / BANQUES CENTRALES AFRICAINES B1 BANK OF KIGALI MR. ALEX BAHIZI NYIRIDANDI OBSERVER C/O Bank of Kigali Ltd Kigarama Kicukiro HEAD OF LEGAL SERVICES 175 kigali Kigali RWANDA MR. JOHN BUGUNYA OBSERVER C/0 Bank of Kigali Limited, 6112, Avenue CHIEF FINANCE OFFICER de la PaixGasabo, Kiyinya 175 175 Kigali RWANDA MR. NAIBO LAWSON OBSERVER KIGALI -RWANDANYARUGENGE CHIEF OPERATIONS OFFICER KIGALI RWANDA MS. LYS MWIZA OBSERVER Bank of Kigali, 6112 avenue de la PRIVATE BANKER paix175 Kigali RWANDA BANK OF KIGALI MR. ENOCK LUYENZI OBSERVER Avenue de la Paix 6112 Kigali Rwanda175 HEAD OF HR&ADMINISTRATION Kigali RWANDA BANK OF MOZAMBIQUE MRS. ESSELINA MAUSSE OBSERVER Av. 25 de Setembro 1695Maputo FOREIGN COOPERATION OFFICER MOZAMBIQUE Observers Final List page 65 SUMMARY ON PARTICIPANTS BANK OF SIERRA LEONE MR. HILTON OLATUNJI JARRETT OBSERVER Sam Bangura BuildingGloucester Street ASSISTANT DIRECTOR, GOVERNOR'S OFFICE 30 Freetown SIERRA LEONE MR. SHEKU SAMBADEEN SESAY HEAD OF INSTITUTION Sam Bangura BuildingGloucester Street GOVERNOR P O Box 30 Freetown SIERRA LEONE BANK OF TANZANIA MR. LAMECK KAKULU OBSERVER 10 Mirambo StreetDar es Salaam FOREIGN EXCHANGE RESERVE MANAGEMENT TANZANIA MR. DAVID MPONEJA OBSERVER BANK OF TANZANIA 2 MIRAMBO HEAD PORTFOLIO MANAGEMENT STREET ,11884 DAR ES SALAAM2939 NONE DAR ES SALAAM TANZANIA BANK OF ZAMBIA DR. EMMANUEL MULENGA PAMU OBSERVER BANK OF ZAMBIA30080 DIRECTOR FINANCIAL MARKETS LUSAKA ZAMBIA MR. BANDA PETER H OBSERVER BANK OF ZAMBIABANK SQUARE SENIOR DIRECTOR - MONETARY POLICY CAIRO ROAD 30080 10101 LUSAKA ZAMBIA Observers Final List page 66 SUMMARY ON PARTICIPANTS BANQUE CENTRALE DE LA REPUBLIQUE DE GUINEE M. -

Media Release 06 August 2020 Access Bank Zambia and Cavmont

Media Release 06 August 2020 Access Bank Zambia and Cavmont Capital Holdings Zambia sign agreement to merge Cavmont Bank with Access Bank Zambia Complementary transaction that combines Access Bank’s wholesale finance capabilities with Cavmont Bank’s retail and commercial banking operations Lusaka – Access Bank Zambia Ltd and Cavmont Capital Holdings Zambia Plc (“CCHZ”) announce that they have signed a definitive agreement regarding a proposed merger of Access Bank Zambia and Cavmont Bank, a subsidiary of CCHZ. Once implemented, the combined bank is expected to boast a strong capital base, in excess of ZMW600 million, significantly exceeding the capital requirement for foreign owned banks under the regulations of the Bank of Zambia. This robust capital structure will not only ensure the banks’ customer deposit base benefits from the greater security but also form the foundation for sustainable banking operations and future growth. The transaction is expected to close during the fourth quarter of 2020 subject to the meeting of various conditions precedent which, amongst others, include CCHZ shareholder approval, relevant regulatory approvals and the local and regional competition commission authorities. The key highlights of the proposed transaction are as follows: A complementary transaction that combines Access Bank Zambia’s wholesale and trade finance capabilities with Cavmont Bank’s retail and commercial banking operations. Access Bank Zambia and Cavmont Bank customers to benefit from greater security offered by one of the most capitalised banks in the country, a more sophisticated product and service offering and a broader geographical network. Following the legal merger of the two banks, the enlarged entity will be a majority owned subsidiary of Access Bank Plc.