Conservation and Monitoring of Invertebrates in Terrestrial Protected Areas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SVP's Letter to Editors of Journals and Publishers on Burmese Amber And

Society of Vertebrate Paleontology 7918 Jones Branch Drive, Suite 300 McLean, VA 22102 USA Phone: (301) 634-7024 Email: [email protected] Web: www.vertpaleo.org FEIN: 06-0906643 April 21, 2020 Subject: Fossils from conflict zones and reproducibility of fossil-based scientific data Dear Editors, We are writing you today to promote the awareness of a couple of troubling matters in our scientific discipline, paleontology, because we value your professional academic publication as an important ‘gatekeeper’ to set high ethical standards in our scientific field. We represent the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology (SVP: http://vertpaleo.org/), a non-profit international scientific organization with over 2,000 researchers, educators, students, and enthusiasts, to advance the science of vertebrate palaeontology and to support and encourage the discovery, preservation, and protection of vertebrate fossils, fossil sites, and their geological and paleontological contexts. The first troubling matter concerns situations surrounding fossils in and from conflict zones. One particularly alarming example is with the so-called ‘Burmese amber’ that contains exquisitely well-preserved fossils trapped in 100-million-year-old (Cretaceous) tree sap from Myanmar. They include insects and plants, as well as various vertebrates such as lizards, snakes, birds, and dinosaurs, which have provided a wealth of biological information about the ‘dinosaur-era’ terrestrial ecosystem. Yet, the scientific value of these specimens comes at a cost (https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/11/science/amber-myanmar-paleontologists.html). Where Burmese amber is mined in hazardous conditions, smuggled out of the country, and sold as gemstones, the most disheartening issue is that the recent surge of exciting scientific discoveries, particularly involving vertebrate fossils, has in part fueled the commercial trading of amber. -

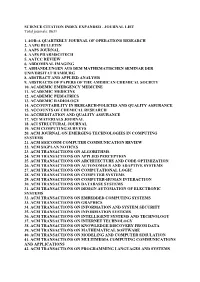

SCIENCE CITATION INDEX EXPANDED - JOURNAL LIST Total Journals: 8631

SCIENCE CITATION INDEX EXPANDED - JOURNAL LIST Total journals: 8631 1. 4OR-A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF OPERATIONS RESEARCH 2. AAPG BULLETIN 3. AAPS JOURNAL 4. AAPS PHARMSCITECH 5. AATCC REVIEW 6. ABDOMINAL IMAGING 7. ABHANDLUNGEN AUS DEM MATHEMATISCHEN SEMINAR DER UNIVERSITAT HAMBURG 8. ABSTRACT AND APPLIED ANALYSIS 9. ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS OF THE AMERICAN CHEMICAL SOCIETY 10. ACADEMIC EMERGENCY MEDICINE 11. ACADEMIC MEDICINE 12. ACADEMIC PEDIATRICS 13. ACADEMIC RADIOLOGY 14. ACCOUNTABILITY IN RESEARCH-POLICIES AND QUALITY ASSURANCE 15. ACCOUNTS OF CHEMICAL RESEARCH 16. ACCREDITATION AND QUALITY ASSURANCE 17. ACI MATERIALS JOURNAL 18. ACI STRUCTURAL JOURNAL 19. ACM COMPUTING SURVEYS 20. ACM JOURNAL ON EMERGING TECHNOLOGIES IN COMPUTING SYSTEMS 21. ACM SIGCOMM COMPUTER COMMUNICATION REVIEW 22. ACM SIGPLAN NOTICES 23. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON ALGORITHMS 24. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON APPLIED PERCEPTION 25. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON ARCHITECTURE AND CODE OPTIMIZATION 26. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON AUTONOMOUS AND ADAPTIVE SYSTEMS 27. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTATIONAL LOGIC 28. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTER SYSTEMS 29. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTER-HUMAN INTERACTION 30. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON DATABASE SYSTEMS 31. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON DESIGN AUTOMATION OF ELECTRONIC SYSTEMS 32. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON EMBEDDED COMPUTING SYSTEMS 33. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON GRAPHICS 34. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INFORMATION AND SYSTEM SECURITY 35. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INFORMATION SYSTEMS 36. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INTELLIGENT SYSTEMS AND TECHNOLOGY 37. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INTERNET TECHNOLOGY 38. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON KNOWLEDGE DISCOVERY FROM DATA 39. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MATHEMATICAL SOFTWARE 40. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MODELING AND COMPUTER SIMULATION 41. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MULTIMEDIA COMPUTING COMMUNICATIONS AND APPLICATIONS 42. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON PROGRAMMING LANGUAGES AND SYSTEMS 43. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON RECONFIGURABLE TECHNOLOGY AND SYSTEMS 44. -

Mollusc Collections at South African Institutions: AUTHOR: Mary Cole1,2 Development and Current Status

Mollusc collections at South African institutions: AUTHOR: Mary Cole1,2 Development and current status AFFILIATIONS: 1East London Museum, East London, South Africa There are three major mollusc collections in South Africa and seven smaller, thematic collections. The 2Department of Zoology and Entomology, Rhodes University, KwaZulu-Natal Museum holds one of the largest collections in the southern hemisphere. Its strengths are Makhanda, South Africa marine molluscs of southern Africa and the southwestern Indian Ocean, and terrestrial molluscs of South Africa. Research on marine molluscs has led to revisionary papers across a wide range of gastropod CORRESPONDENCE TO: Mary Cole families. The Iziko South African Museum contains the most comprehensive collections of Cephalopoda (octopus, squid and relatives) and Polyplacophora (chitons) for southern Africa. The East London Museum EMAIL: [email protected] is a provincial museum of the Eastern Cape. Recent research focuses on terrestrial molluscs and the collection is growing to address the gap in knowledge of this element of biodiversity. Mollusc collections DATES: in South Africa date to about 1900 and are an invaluable resource of morphological and genetic diversity, Received: 06 Oct. 2020 with associated spatial and temporal data. The South African National Biodiversity Institute is encouraging Revised: 10 Dec. 2020 Accepted: 12 Feb 2021 discovery and documentation to address gaps in knowledge, particularly of invertebrates. Museums are Published: 29 July 2021 supported with grants for surveys, systematic studies and data mobilisation. The Department of Science and Innovation is investing in collections as irreplaceable research infrastructure through the Natural HOW TO CITE: Cole M. Mollusc collections at South Science Collections Facility, whereby 16 institutions, including those holding mollusc collections, are African institutions: Development assisted to achieve common targets and coordinated outputs. -

SPP Social Agri 2010 Layout 1

© Academy of Science of South Africa, August 2010 ISBN 978-0-9814159-9-4 Published by: Academy of Science of South Africa (ASSAf) PO Box 72135, Lynnwood Ridge, Pretoria, South Africa, 0040 Tel: +27 12 349 6600 • Fax: +27 86 576 9520 E-mail: [email protected] Reproduction is permitted, provided the source and publisher are appropriately acknowledged. The Academy of Science of South Africa (ASSAf) was inaugurated in May 1996 in the presence of then President Nelson Mandela, the Patron of the launch of the Academy. It was formed in response to the need for an Academy of Science consonant with the dawn of democracy in South Africa: activist in its mission of using science for the benefit of society, with a mandate encompassing all fields of scientific enquiry in a seamless way, and including in its ranks the full diversity of South Africa's distinguished scientists. The Parliament of South Africa passed the Academy of Science of South Africa Act (Act 67 in 2001) which came into operation on 15 May 2002. This has made ASSAf the official Academy of Science of South Africa, recognised by government and representing South Africa in the international community of science academies. COMMITTEE ON SCHOLARLY PUBLISHING IN SOUTH AFRICA Report on Peer Review of Scholarly Journals in the Agricultural and related Basic Life Sciences August 2010 2 REPORT ON PEER REVIEW OF SCHOLARLY JOURNALS IN THE AGRICULTURAL AND RELATED BASIC LIFE SCIENCES TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE 5 FOREWORD 7 1 PERIODIC PEER REVIEW OF SOUTH AFRICAN SCHOLARLY JOURNALS: 9 APPROVED PROCESS GUIDELINES AND CRITERIA 1.1 Background 9 1.2 ASSAf peer review panels 9 1.3 Initial criteria 10 1.4 Process guidelines 11 1.4.1 Selecting panel members 12 1.4.2 Setting up and organising the panels 12 1.4.3 Peer reviews 13 1.4.4 Panel reports 13 2 SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS CONCERNING SOUTH AFRICAN 13 AGRICULTURAL AND RELATED BASIC LIFE SCIENCE JOURNALS 3 PANEL MEMBERS 14 4 CONSENSUS REVIEWS OF JOURNALS IN THE AGRICULTURAL AND RELATED BASIC LIFE SCIENCES 15 I. -

Significance of Specimen Databases from Taxonomic Revisions For

Significance of Specimen Databases from Taxonomic Revisions for Estimating and Mapping the Global Species Diversity of Invertebrates and Repatriating Reliable Specimen Data RUDOLF MEIER∗ AND TORSTEN DIKOW† ∗Zoological Museum, Universitetsparken 15, DK-2100 Copenhagen Ø, Denmark, and Department of Biological Sciences, National University of Singapore, 14 Science Drive 4, Singapore 117543, email [email protected] †Universit¨at Rostock Institut f¨ur Biodiversit¨atsforschung, Allgemeine und Spezielle Zoologie, Uniplatz 2, D-18055 Rostock, Germany, and Cornell University, Department of Entomology, Comstock Hall, Ithaca, NY 14853, U.S.A. Abstract: We argue that the millions of specimen-label records published over the past decades in thousands of taxonomic revisions are a cost-effective source of information of critical importance for incorporating invertebrates into biodiversity research and conservation decisions. More specifically, we demonstrate for a specimen database assembled during a revision of the robber-fly genus Euscelidia (Asilidae, Diptera) how nonparametric species richness estimators (Chao1, incidence-based coverage estimator,second-order jackknife) can be used to (1) estimate global species diversity, (2) direct future collecting to areas that are undersampled and/or likely to be rich in new species, and (3) assess whether the plant-based global biodiversity hotspots of Myers et al. (2000) contain a significant proportion of invertebrates. During the revision of Euscelidia, the number of known species more than doubled, but estimation of species richness revealed that the true diversity of the genus was likely twice as high. The same techniques applied to subsamples of the data indicated that much of the unknown diversity will be found in the Oriental region. -

Madagascar's Living Giants: African Invertebrates 2010

African Invertebrates Vol. 51 (1) Pages 133–161 Pietermaritzburg May, 2010 Madagascar’s living giants: discovery of five new species of endemic giant pill-millipedes from Madagascar (Diplopoda: Sphaerotheriida: Arthrosphaeridae: Zoosphaerium) Thomas Wesener1*, Ioulia Bespalova2 and Petra Sierwald1 1Field Museum of Natural History, Zoology – Insects, 1400 S. Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, Illinois, 60605 USA; [email protected] 2Mount Holyoke College, 50 College St., South Hadley, Massachusetts, 01075 USA *Author for correspondence ABSTRACT Five new species of the endemic giant pill-millipede genus Zoosphaerium from Madagascar are des- cribed: Z. muscorum sp. n., Z. bambusoides sp. n., Z. tigrioculatum sp. n., Z. darthvaderi sp. n., and Z. he- leios sp. n. The first three species fit into the Z. coquerelianum species-group, where Z. tigrioculatum seems to be closely related to Z. isalo Wesener, 2009 and Z. bilobum Wesener, 2009. Z. tigrioculatum is also the giant pill-millipede species currently known from the highest elevation, up 2000 m on Mt Andringitra. Z. muscorum and Z. darthvaderi were both collected in mossy forest at over 1000 m (albeit at distant localities), obviously a previously undersampled ecosystem. Z. darthvaderi and Z. heleios both possess very unusual characters, not permitting their placement in any existing species-group, putting them in an isolated position. The females of Z. xerophilum Wesener, 2009 and Z. pseudoplatylabum Wesener, 2009 are described for the first time, both from samples collected close to their type localities. The vulva and washboard of Z. pseudoplatylabum fit very well into the Z. platylabum species-group. Additional locality and specimen information is given for nine species of Zoosphaerium: Z. -

2018 Journal Citation Reports Journals in the 2018 Release of JCR 2 Journals in the 2018 Release of JCR

2018 Journal Citation Reports Journals in the 2018 release of JCR 2 Journals in the 2018 release of JCR Abbreviated Title Full Title Country/Region SCIE SSCI 2D MATER 2D MATERIALS England ✓ 3 BIOTECH 3 BIOTECH Germany ✓ 3D PRINT ADDIT MANUF 3D PRINTING AND ADDITIVE MANUFACTURING United States ✓ 4OR-A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF 4OR-Q J OPER RES OPERATIONS RESEARCH Germany ✓ AAPG BULL AAPG BULLETIN United States ✓ AAPS J AAPS JOURNAL United States ✓ AAPS PHARMSCITECH AAPS PHARMSCITECH United States ✓ AATCC J RES AATCC JOURNAL OF RESEARCH United States ✓ AATCC REV AATCC REVIEW United States ✓ ABACUS-A JOURNAL OF ACCOUNTING ABACUS FINANCE AND BUSINESS STUDIES Australia ✓ ABDOM IMAGING ABDOMINAL IMAGING United States ✓ ABDOM RADIOL ABDOMINAL RADIOLOGY United States ✓ ABHANDLUNGEN AUS DEM MATHEMATISCHEN ABH MATH SEM HAMBURG SEMINAR DER UNIVERSITAT HAMBURG Germany ✓ ACADEMIA-REVISTA LATINOAMERICANA ACAD-REV LATINOAM AD DE ADMINISTRACION Colombia ✓ ACAD EMERG MED ACADEMIC EMERGENCY MEDICINE United States ✓ ACAD MED ACADEMIC MEDICINE United States ✓ ACAD PEDIATR ACADEMIC PEDIATRICS United States ✓ ACAD PSYCHIATR ACADEMIC PSYCHIATRY United States ✓ ACAD RADIOL ACADEMIC RADIOLOGY United States ✓ ACAD MANAG ANN ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT ANNALS United States ✓ ACAD MANAGE J ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT JOURNAL United States ✓ ACAD MANAG LEARN EDU ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT LEARNING & EDUCATION United States ✓ ACAD MANAGE PERSPECT ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT PERSPECTIVES United States ✓ ACAD MANAGE REV ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT REVIEW United States ✓ ACAROLOGIA ACAROLOGIA France ✓ -

An Assessment of South Africa's Research

An assessment of South Africa’s research journals: impact factors, Eigenfactors and the structure of editorial boards Androniki EM Pouris and Prof Anastassios Pouris Journals are the main Researchers would like as well-known researchers particular year. Despite the to know where to publish and deans of faculties are continuous debate related vehicles for scholarly in order to maximise asked to assess particular to the validity of Garfield’s the exposure of their journals. Subsequently, journal impact factor for communication research and what to read the collected opinions the identification of the in order to keep abreast are aggregated and a journal’s standing, citation within the academic of developments in their relative statement can analysis has prevailed in community. As such, fields. Librarians would like be made. However, this the past (Vanclay, 2012; to have the most reputed approach has the same Bensman, 2012). assessments of journals journals available, and drawbacks as peer review. research administrators Will the opinions remain Scientific publishing are of interest to a use journal assessments the same if the experts in South Africa has in their evaluations of were different? How can experienced a revolution number of stakeholders, academics for recruitment, an astronomer assess a during the last ten years. promotion and funding plant science journal? Are In 2000, the South African from scientists and purposes. Editors are there unbiased researchers government terminated interested to know the in scientifically small its direct financial support librarians to research relative performance of countries? to research journals and administrators, editors, their journal in comparison only the South African with competitor journals. -

The South African National Red List of Spiders: Patterns, Threats, and Conservation

2020. Journal of Arachnology 48:110–118 The South African National Red List of spiders: patterns, threats, and conservation Stefan H. Foord1, Anna S. Dippenaar-Schoeman1,2, Charles R. Haddad3, Robin Lyle2, Leon N. Lotz4, Theresa Sethusa5 and Domitilla Raimondo5: 1Department of Zoology and Centre for Invasion Biology, University of Venda, Thohoyandou, South Africa; E-mail: [email protected] 2Biosystematics: Arachnology, ARC – Plant Health and Protection, Pretoria, South Africa; 3Department of Zoology & Entomology, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa; 4Department of Arachnology, National Museum, Bloemfontein, South Africa; 5South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, South Africa Abstract. Triage in conservation biology necessitates the prioritization of species and ecosystems for conservation. Although highly diverse, ecologically important, and charismatic, spiders are rarely considered. With 2,253 known species, South Africa’s spider diversity is among the highest in the world. A 22-year initiative culminating in a national assessment of all the South African species saw a 33% increase in described species and a 350% rise in specimen accessions of the national collection annually. Endemism is high, at 60% of all South African species. Levels of endemicity are particularly high in Fynbos, Succulent Karroo and Forests. Relative to its area, Forests have three times more endemics than any of the other biomes, followed by the Indian Ocean Coastal Belt. A total of 127 species (5.7%) are either rare or endangered. Threats to these species are largely linked to habitat destruction in the form of urbanization and agriculture. The bulk (62.8%) of taxa are of least concern, but many species are data deficient (27%). -

Africana E-Journals Finding

Compiled by Angel D. Batiste, Area Specialist, African Section This online directory provides a listing of selected journals related to the field of African Studies that are available in electronic format, also known as e-journals. It includes both western e-journals and e-journals published in Africa that are accessible in full text format in major commercial and open access databases on the Internet. Journal titles are listed in alphabetical order with the database source location. NOTE: Many of the electronic journals which are listed exist in print format. Title of E-Journal Database Source Abasebenzi Open Access ABSA Bank Econo-Weekly Westlaw Acta Borealia: A Nordic Journal of Circumpolar Taylor & Francis Societies Addis Tribune Westlaw ADEA Newsletter Open Access ADP News Middle East and Africa Aequatoria: Revue des Sciences Congolaises Open Access Afra Newsletter Open Access Africa Cambridge Journals Online Africa & Asia: Goteborg Working Papers on Asian and African Languages and Literatures Africa & The Middle East Telecom ProQuest Dialog; Westlaw; Eureka; Europresse; LexisNexis; Newscan Africa Action Westlaw Africa Analysis LexisNexis; Westlaw; ProQuest; ProQuest Dialog Africa Bibliography Cambridge Journals Online Africa Book Centre Book Review, The Open Access Africa Confidential EBSCOhost; Wiley Online Library Africa Development Open Access Africa Dialogue Monograph Series Sabinet Africa Education Review Taylor & Francis Africa Energy and Mining LexisNexis Africa Energy Intelligence Dow Jones Factiva; LexisNexis; Eureka; Europresse; -

An Assessment of South Africa's Research Journals

Research Article Impact factors, Eigenfactors and structure of editorial boards Page 1 of 8 An assessment of South Africa’s research journals: AUTHORS: Impact factors, Eigenfactors and structure of Androniki E.M. Pouris1 Anastassios Pouris2 editorial boards AFFILIATIONS: 1Faculty of Science, Tshwane Scientific journals play an important role in academic information exchange and their assessment is of University of Technology, interest to science authorities, editors and researchers. The assessment of journals is of particular interest Pretoria, South Africa to South African authorities as the country’s universities are partially funded according to the number of 2 Institute for Technological publications they produce in accredited journals, such as the Thomson Reuters indexed journals. Scientific Innovation, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa publishing in South Africa has experienced a revolution during the last 10 years. Our objective here is to report the performance of the country’s journals during 2009 and 2010 according to a number of metrics (i.e. ® CORRESPONDENCE TO: impact factors, Eigenfactors and the international character of editorial boards); to identify and compare the Anastassios Pouris impact of the South African journals that have been recently added to the Thomson Reuters' Journal Citation Reports®; and to elaborate on issues related to science policy. EMAIL: [email protected] Introduction POSTAL ADDRESS: Journals are the main vehicle for scholarly communication within the academic community. As such, assessments Institute for Technological of journals are of interest to a number of stakeholders from scientists and librarians to research administrators, Innovation, Engineering editors, policy analysts and policymakers and for a variety of reasons. -

Lorenzo Prendini, Ph.D

Curriculum Vitae: Lorenzo Prendini, Ph.D. Associate Curator, Arachnids & Myriapods Division of Invertebrate Zoology American Museum of Natural History Central Park West at 79th Street New York, NY 10024-5192, USA tel: +1-212-769-5843; fax: +1-212-769-5277 email: [email protected] Scorpion Systematics Research Group: http://scorpion.amnh.org RevSys: North American Scorpion Family Vaejovidae: http://www.vaejovidae.com BS&I: Global Survey and Inventory of Solifugae: http://www.solpugid.com AToL: Phylogeny of Spiders: http://research.amnh.org/atol/files Education Ph.D., Zoology, University of Cape Town, South Africa (2001) B.Sc. (Hons), Zoology, University of Cape Town, South Africa, (1995) B.Sc., Botany & Zoology, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa (1994) Appointments Associate Curator, Division of Invertebrate Zoology, AMNH (2007–) Assistant Curator, Division of Invertebrate Zoology, AMNH (2002–) Adjunct Appointments Adjunct Professor, Colorado State University (2008–) Research Associate, National Museum of Namibia (2006–) Research Associate, Transvaal Museum of Natural History, Pretoria, South Africa (2004–) Adjunct Professor, Department of Entomology, Cornell University (2004–) Adjunct Professor, Department of Biology, CUNY (2003–) Editorial Positions Associate Editor, ZOOTAXA (2005–) Associate Editor, Cladistics (2004–) Associate Editor, Journal of Afrotropical Zoology (2004–) Professional Affiliations African Arachnological Society; American Arachnological Society; Entomological Society of Southern Africa; The Explorer’s Club (Fellow); International Society of Arachnology (Executive Committee, 2007–); Society of Systematic Biologists; South African Society of Systematic Biology; Willi Hennig Society (Fellow); Zoological Society of Southern Africa. Scientific Publications Peer-reviewed Journal Articles: Prendini, L., Theron. L-J., Van der Merwe, K. and Owen-Smith, N. 1996. Abundance and guild structure of grasshoppers (Orthoptera: Acridoidea) in communally grazed and protected savanna.