Significance of Specimen Databases from Taxonomic Revisions For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SVP's Letter to Editors of Journals and Publishers on Burmese Amber And

Society of Vertebrate Paleontology 7918 Jones Branch Drive, Suite 300 McLean, VA 22102 USA Phone: (301) 634-7024 Email: [email protected] Web: www.vertpaleo.org FEIN: 06-0906643 April 21, 2020 Subject: Fossils from conflict zones and reproducibility of fossil-based scientific data Dear Editors, We are writing you today to promote the awareness of a couple of troubling matters in our scientific discipline, paleontology, because we value your professional academic publication as an important ‘gatekeeper’ to set high ethical standards in our scientific field. We represent the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology (SVP: http://vertpaleo.org/), a non-profit international scientific organization with over 2,000 researchers, educators, students, and enthusiasts, to advance the science of vertebrate palaeontology and to support and encourage the discovery, preservation, and protection of vertebrate fossils, fossil sites, and their geological and paleontological contexts. The first troubling matter concerns situations surrounding fossils in and from conflict zones. One particularly alarming example is with the so-called ‘Burmese amber’ that contains exquisitely well-preserved fossils trapped in 100-million-year-old (Cretaceous) tree sap from Myanmar. They include insects and plants, as well as various vertebrates such as lizards, snakes, birds, and dinosaurs, which have provided a wealth of biological information about the ‘dinosaur-era’ terrestrial ecosystem. Yet, the scientific value of these specimens comes at a cost (https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/11/science/amber-myanmar-paleontologists.html). Where Burmese amber is mined in hazardous conditions, smuggled out of the country, and sold as gemstones, the most disheartening issue is that the recent surge of exciting scientific discoveries, particularly involving vertebrate fossils, has in part fueled the commercial trading of amber. -

The Flower Flies and the Unknown Diversity of Drosophilidae (Diptera): a Biodiversity Inventory in the Brazilian Fauna

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/402834; this version posted August 29, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. The flower flies and the unknown diversity of Drosophilidae (Diptera): a biodiversity inventory in the Brazilian fauna Hermes J. Schmitz1 and Vera L. S. Valente2 1 Universidade Federal da Integração-Latino-Americana, Foz do Iguaçu, PR, Brazil; [email protected] 2 Programa de Pós-Graduação em Genética e Biologia Molecular, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil; [email protected] Abstract Diptera is a megadiverse order, reaching its peak of diversity in Neotropics, although our knowledge of dipteran fauna of this region is grossly deficient. This applies even for the most studied families, as Drosophilidae. Despite its position of evidence, most aspects of the biology of these insects are still poorly understood, especially those linked to natural communities. Field studies on drosophilids are highly biased to fruit-breeders species. Flower-breeding drosophilids, however, are worldwide distributed, especially in tropical regions, although being mostly neglected. The present paper shows results of a biodiversity inventory of flower-breeding drosophilids carried out in Brazil, based on samples of 125 plant species, from 47 families. Drosophilids were found in flowers of 56 plant species, of 18 families. The fauna discovered showed to be highly unknown, comprising 28 species, 12 of them (>40%) still undescribed. -

Diptera) Diversity in a Patch of Costa Rican Cloud Forest: Why Inventory Is a Vital Science

Zootaxa 4402 (1): 053–090 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2018 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4402.1.3 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:C2FAF702-664B-4E21-B4AE-404F85210A12 Remarkable fly (Diptera) diversity in a patch of Costa Rican cloud forest: Why inventory is a vital science ART BORKENT1, BRIAN V. BROWN2, PETER H. ADLER3, DALTON DE SOUZA AMORIM4, KEVIN BARBER5, DANIEL BICKEL6, STEPHANIE BOUCHER7, SCOTT E. BROOKS8, JOHN BURGER9, Z.L. BURINGTON10, RENATO S. CAPELLARI11, DANIEL N.R. COSTA12, JEFFREY M. CUMMING8, GREG CURLER13, CARL W. DICK14, J.H. EPLER15, ERIC FISHER16, STEPHEN D. GAIMARI17, JON GELHAUS18, DAVID A. GRIMALDI19, JOHN HASH20, MARTIN HAUSER17, HEIKKI HIPPA21, SERGIO IBÁÑEZ- BERNAL22, MATHIAS JASCHHOF23, ELENA P. KAMENEVA24, PETER H. KERR17, VALERY KORNEYEV24, CHESLAVO A. KORYTKOWSKI†, GIAR-ANN KUNG2, GUNNAR MIKALSEN KVIFTE25, OWEN LONSDALE26, STEPHEN A. MARSHALL27, WAYNE N. MATHIS28, VERNER MICHELSEN29, STEFAN NAGLIS30, ALLEN L. NORRBOM31, STEVEN PAIERO27, THOMAS PAPE32, ALESSANDRE PEREIRA- COLAVITE33, MARC POLLET34, SABRINA ROCHEFORT7, ALESSANDRA RUNG17, JUSTIN B. RUNYON35, JADE SAVAGE36, VERA C. SILVA37, BRADLEY J. SINCLAIR38, JEFFREY H. SKEVINGTON8, JOHN O. STIREMAN III10, JOHN SWANN39, PEKKA VILKAMAA40, TERRY WHEELER††, TERRY WHITWORTH41, MARIA WONG2, D. MONTY WOOD8, NORMAN WOODLEY42, TIFFANY YAU27, THOMAS J. ZAVORTINK43 & MANUEL A. ZUMBADO44 †—deceased. Formerly with the Universidad de Panama ††—deceased. Formerly at McGill University, Canada 1. Research Associate, Royal British Columbia Museum and the American Museum of Natural History, 691-8th Ave. SE, Salmon Arm, BC, V1E 2C2, Canada. Email: [email protected] 2. -

Venom Week 2012 4Th International Scientific Symposium on All Things Venomous

17th World Congress of the International Society on Toxinology Animal, Plant and Microbial Toxins & Venom Week 2012 4th International Scientific Symposium on All Things Venomous Honolulu, Hawaii, USA, July 8 – 13, 2012 1 Table of Contents Section Page Introduction 01 Scientific Organizing Committee 02 Local Organizing Committee / Sponsors / Co-Chairs 02 Welcome Messages 04 Governor’s Proclamation 08 Meeting Program 10 Sunday 13 Monday 15 Tuesday 20 Wednesday 26 Thursday 30 Friday 36 Poster Session I 41 Poster Session II 47 Supplemental program material 54 Additional Abstracts (#298 – #344) 61 International Society on Thrombosis & Haemostasis 99 2 Introduction Welcome to the 17th World Congress of the International Society on Toxinology (IST), held jointly with Venom Week 2012, 4th International Scientific Symposium on All Things Venomous, in Honolulu, Hawaii, USA, July 8 – 13, 2012. This is a supplement to the special issue of Toxicon. It contains the abstracts that were submitted too late for inclusion there, as well as a complete program agenda of the meeting, as well as other materials. At the time of this printing, we had 344 scientific abstracts scheduled for presentation and over 300 attendees from all over the planet. The World Congress of IST is held every three years, most recently in Recife, Brazil in March 2009. The IST World Congress is the primary international meeting bringing together scientists and physicians from around the world to discuss the most recent advances in the structure and function of natural toxins occurring in venomous animals, plants, or microorganisms, in medical, public health, and policy approaches to prevent or treat envenomations, and in the development of new toxin-derived drugs. -

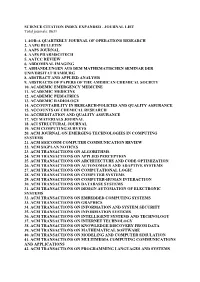

SCIENCE CITATION INDEX EXPANDED - JOURNAL LIST Total Journals: 8631

SCIENCE CITATION INDEX EXPANDED - JOURNAL LIST Total journals: 8631 1. 4OR-A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF OPERATIONS RESEARCH 2. AAPG BULLETIN 3. AAPS JOURNAL 4. AAPS PHARMSCITECH 5. AATCC REVIEW 6. ABDOMINAL IMAGING 7. ABHANDLUNGEN AUS DEM MATHEMATISCHEN SEMINAR DER UNIVERSITAT HAMBURG 8. ABSTRACT AND APPLIED ANALYSIS 9. ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS OF THE AMERICAN CHEMICAL SOCIETY 10. ACADEMIC EMERGENCY MEDICINE 11. ACADEMIC MEDICINE 12. ACADEMIC PEDIATRICS 13. ACADEMIC RADIOLOGY 14. ACCOUNTABILITY IN RESEARCH-POLICIES AND QUALITY ASSURANCE 15. ACCOUNTS OF CHEMICAL RESEARCH 16. ACCREDITATION AND QUALITY ASSURANCE 17. ACI MATERIALS JOURNAL 18. ACI STRUCTURAL JOURNAL 19. ACM COMPUTING SURVEYS 20. ACM JOURNAL ON EMERGING TECHNOLOGIES IN COMPUTING SYSTEMS 21. ACM SIGCOMM COMPUTER COMMUNICATION REVIEW 22. ACM SIGPLAN NOTICES 23. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON ALGORITHMS 24. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON APPLIED PERCEPTION 25. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON ARCHITECTURE AND CODE OPTIMIZATION 26. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON AUTONOMOUS AND ADAPTIVE SYSTEMS 27. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTATIONAL LOGIC 28. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTER SYSTEMS 29. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTER-HUMAN INTERACTION 30. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON DATABASE SYSTEMS 31. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON DESIGN AUTOMATION OF ELECTRONIC SYSTEMS 32. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON EMBEDDED COMPUTING SYSTEMS 33. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON GRAPHICS 34. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INFORMATION AND SYSTEM SECURITY 35. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INFORMATION SYSTEMS 36. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INTELLIGENT SYSTEMS AND TECHNOLOGY 37. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INTERNET TECHNOLOGY 38. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON KNOWLEDGE DISCOVERY FROM DATA 39. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MATHEMATICAL SOFTWARE 40. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MODELING AND COMPUTER SIMULATION 41. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MULTIMEDIA COMPUTING COMMUNICATIONS AND APPLICATIONS 42. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON PROGRAMMING LANGUAGES AND SYSTEMS 43. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON RECONFIGURABLE TECHNOLOGY AND SYSTEMS 44. -

Competence of the Vector Restricting Tick-Borne Encephalitis Virus Spread

University of Veterinary Medicine Hannover Institute for Parasitology Competence of the vector restricting tick-borne encephalitis virus spread THESIS Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Natural Sciences Doctor rerum naturalium (Dr. rer. nat.) awarded by the University of Veterinary Medicine Hannover by Katrin Liebig from Rheda-Wiedenbrück Hannover, Germany 2020 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Stefanie Becker Supervision Group: Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Stefanie Becker Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Klaus Jung PD Dr. med. habil. Gerhard Dobler 1st Evaluation: Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Stefanie Becker Institute for Parasitology and Research Center for Emerging Infections and Zoonoses University of Veterinary Medicine Hannover, Foundation Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Klaus Jung Institute for Animal Breeding and Genetics University of Veterinary Medicine Hannover, Foundation PD Dr. med. habil. Gerhard Dobler Institute for Microbiology of the Bundeswehr Parasitology Unit, University of Hohenheim 2nd Evaluation: Prof. Dr. med. vet. Martin Pfeffer Institute of Animal Hygiene and Veterinary Public Health University of Leipzig Date of final exam: 29.10.2020 This work was funded by the German research foundation and the TBENAGER consortium. Parts of the present thesis have been either accepted for publication or prepared for submission Accepted for publication Liebig, K., Boelke, M., Grund, D., Schicht, S., Springer, A. Strube, C., Chitimia-Dobler, L., Dobler, G. Jung, K., Becker, S. Tick populations from endemic and non-endemic areas in Germany show differential susceptibility to TBEV. Sci Rep 10, 15478 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-71920-z Prepared for submission Liebig, K., Boelke, M., Grund, D., Schicht, S., Bestehorn-Willmann, M., Chitimia-Dobler, L., Dobler, G. -

Mollusc Collections at South African Institutions: AUTHOR: Mary Cole1,2 Development and Current Status

Mollusc collections at South African institutions: AUTHOR: Mary Cole1,2 Development and current status AFFILIATIONS: 1East London Museum, East London, South Africa There are three major mollusc collections in South Africa and seven smaller, thematic collections. The 2Department of Zoology and Entomology, Rhodes University, KwaZulu-Natal Museum holds one of the largest collections in the southern hemisphere. Its strengths are Makhanda, South Africa marine molluscs of southern Africa and the southwestern Indian Ocean, and terrestrial molluscs of South Africa. Research on marine molluscs has led to revisionary papers across a wide range of gastropod CORRESPONDENCE TO: Mary Cole families. The Iziko South African Museum contains the most comprehensive collections of Cephalopoda (octopus, squid and relatives) and Polyplacophora (chitons) for southern Africa. The East London Museum EMAIL: [email protected] is a provincial museum of the Eastern Cape. Recent research focuses on terrestrial molluscs and the collection is growing to address the gap in knowledge of this element of biodiversity. Mollusc collections DATES: in South Africa date to about 1900 and are an invaluable resource of morphological and genetic diversity, Received: 06 Oct. 2020 with associated spatial and temporal data. The South African National Biodiversity Institute is encouraging Revised: 10 Dec. 2020 Accepted: 12 Feb 2021 discovery and documentation to address gaps in knowledge, particularly of invertebrates. Museums are Published: 29 July 2021 supported with grants for surveys, systematic studies and data mobilisation. The Department of Science and Innovation is investing in collections as irreplaceable research infrastructure through the Natural HOW TO CITE: Cole M. Mollusc collections at South Science Collections Facility, whereby 16 institutions, including those holding mollusc collections, are African institutions: Development assisted to achieve common targets and coordinated outputs. -

SPP Social Agri 2010 Layout 1

© Academy of Science of South Africa, August 2010 ISBN 978-0-9814159-9-4 Published by: Academy of Science of South Africa (ASSAf) PO Box 72135, Lynnwood Ridge, Pretoria, South Africa, 0040 Tel: +27 12 349 6600 • Fax: +27 86 576 9520 E-mail: [email protected] Reproduction is permitted, provided the source and publisher are appropriately acknowledged. The Academy of Science of South Africa (ASSAf) was inaugurated in May 1996 in the presence of then President Nelson Mandela, the Patron of the launch of the Academy. It was formed in response to the need for an Academy of Science consonant with the dawn of democracy in South Africa: activist in its mission of using science for the benefit of society, with a mandate encompassing all fields of scientific enquiry in a seamless way, and including in its ranks the full diversity of South Africa's distinguished scientists. The Parliament of South Africa passed the Academy of Science of South Africa Act (Act 67 in 2001) which came into operation on 15 May 2002. This has made ASSAf the official Academy of Science of South Africa, recognised by government and representing South Africa in the international community of science academies. COMMITTEE ON SCHOLARLY PUBLISHING IN SOUTH AFRICA Report on Peer Review of Scholarly Journals in the Agricultural and related Basic Life Sciences August 2010 2 REPORT ON PEER REVIEW OF SCHOLARLY JOURNALS IN THE AGRICULTURAL AND RELATED BASIC LIFE SCIENCES TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE 5 FOREWORD 7 1 PERIODIC PEER REVIEW OF SOUTH AFRICAN SCHOLARLY JOURNALS: 9 APPROVED PROCESS GUIDELINES AND CRITERIA 1.1 Background 9 1.2 ASSAf peer review panels 9 1.3 Initial criteria 10 1.4 Process guidelines 11 1.4.1 Selecting panel members 12 1.4.2 Setting up and organising the panels 12 1.4.3 Peer reviews 13 1.4.4 Panel reports 13 2 SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS CONCERNING SOUTH AFRICAN 13 AGRICULTURAL AND RELATED BASIC LIFE SCIENCE JOURNALS 3 PANEL MEMBERS 14 4 CONSENSUS REVIEWS OF JOURNALS IN THE AGRICULTURAL AND RELATED BASIC LIFE SCIENCES 15 I. -

Acanoides Gen. N., a New Spider Genus from China with a Note on the Taxonomic Status of Acanthoneta Eskov & Marusik, 1992 (Araneae, Linyphiidae, Micronetinae)

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 375: 75–99 (2014) Acanoides gen. n. from China 75 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.375.6116 RESEARCH ARTICLE www.zookeys.org Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Acanoides gen. n., a new spider genus from China with a note on the taxonomic status of Acanthoneta Eskov & Marusik, 1992 (Araneae, Linyphiidae, Micronetinae) Ning Sun1,†, Yuri M. Marusik2,3,‡, Lihong Tu1,§ 1 College of Life Sciences, Capital Normal University, Xisanhuanbeilu Str. 105, Haidian Dist., Beijing, 100048, P. R. China 2 Institute for Biological Problems of the North, FEB Russian Academy of Sciences, Porto- vaya Str. 18, Magadan, 685000, Russia 3 Zoological Museum, University of Turku, FI-20014 Turku, Finland † http://zoobank.org/3EF5007C-4FF8-4642-B18F-57104A493701 ‡ http://zoobank.org/F215BA2C-5072-4CBF-BA1A-5CCBE1626B08 § http://zoobank.org/76D0E0A4-59E4-4087-8239-FBAC3A137AB1 Corresponding author: Lihong Tu ([email protected]) Academic editor: D. Dimitrov | Received 17 August 2013 | Accepted 16 December 2013 | Published 30 January 2014 http://zoobank.org/319CFD1C-A795-4F2E-A20D-9284BCC2C3F7 Citation: Sun N, Marusik YM, Tu L (2014) Acanoides gen. n., a new spider genus from China with a note on the taxonomic status of Acanthoneta Eskov & Marusik, 1992 (Araneae, Linyphiidae, Micronetinae). ZooKeys 375: 75–99. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.375.6116 Abstract A new “micronetine” genus Acanoides gen. n. is erected to accommodate two species from China: Aca- noides beijingensis sp. n. as the type species and Acanoides hengshanensis (Chen & Yin, 2000), comb. n., with the females described for the first time. The genitalic characters and somatic features of the new genus were studied by means of light microscopy and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). -

Madagascar's Living Giants: African Invertebrates 2010

African Invertebrates Vol. 51 (1) Pages 133–161 Pietermaritzburg May, 2010 Madagascar’s living giants: discovery of five new species of endemic giant pill-millipedes from Madagascar (Diplopoda: Sphaerotheriida: Arthrosphaeridae: Zoosphaerium) Thomas Wesener1*, Ioulia Bespalova2 and Petra Sierwald1 1Field Museum of Natural History, Zoology – Insects, 1400 S. Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, Illinois, 60605 USA; [email protected] 2Mount Holyoke College, 50 College St., South Hadley, Massachusetts, 01075 USA *Author for correspondence ABSTRACT Five new species of the endemic giant pill-millipede genus Zoosphaerium from Madagascar are des- cribed: Z. muscorum sp. n., Z. bambusoides sp. n., Z. tigrioculatum sp. n., Z. darthvaderi sp. n., and Z. he- leios sp. n. The first three species fit into the Z. coquerelianum species-group, where Z. tigrioculatum seems to be closely related to Z. isalo Wesener, 2009 and Z. bilobum Wesener, 2009. Z. tigrioculatum is also the giant pill-millipede species currently known from the highest elevation, up 2000 m on Mt Andringitra. Z. muscorum and Z. darthvaderi were both collected in mossy forest at over 1000 m (albeit at distant localities), obviously a previously undersampled ecosystem. Z. darthvaderi and Z. heleios both possess very unusual characters, not permitting their placement in any existing species-group, putting them in an isolated position. The females of Z. xerophilum Wesener, 2009 and Z. pseudoplatylabum Wesener, 2009 are described for the first time, both from samples collected close to their type localities. The vulva and washboard of Z. pseudoplatylabum fit very well into the Z. platylabum species-group. Additional locality and specimen information is given for nine species of Zoosphaerium: Z. -

2018 Journal Citation Reports Journals in the 2018 Release of JCR 2 Journals in the 2018 Release of JCR

2018 Journal Citation Reports Journals in the 2018 release of JCR 2 Journals in the 2018 release of JCR Abbreviated Title Full Title Country/Region SCIE SSCI 2D MATER 2D MATERIALS England ✓ 3 BIOTECH 3 BIOTECH Germany ✓ 3D PRINT ADDIT MANUF 3D PRINTING AND ADDITIVE MANUFACTURING United States ✓ 4OR-A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF 4OR-Q J OPER RES OPERATIONS RESEARCH Germany ✓ AAPG BULL AAPG BULLETIN United States ✓ AAPS J AAPS JOURNAL United States ✓ AAPS PHARMSCITECH AAPS PHARMSCITECH United States ✓ AATCC J RES AATCC JOURNAL OF RESEARCH United States ✓ AATCC REV AATCC REVIEW United States ✓ ABACUS-A JOURNAL OF ACCOUNTING ABACUS FINANCE AND BUSINESS STUDIES Australia ✓ ABDOM IMAGING ABDOMINAL IMAGING United States ✓ ABDOM RADIOL ABDOMINAL RADIOLOGY United States ✓ ABHANDLUNGEN AUS DEM MATHEMATISCHEN ABH MATH SEM HAMBURG SEMINAR DER UNIVERSITAT HAMBURG Germany ✓ ACADEMIA-REVISTA LATINOAMERICANA ACAD-REV LATINOAM AD DE ADMINISTRACION Colombia ✓ ACAD EMERG MED ACADEMIC EMERGENCY MEDICINE United States ✓ ACAD MED ACADEMIC MEDICINE United States ✓ ACAD PEDIATR ACADEMIC PEDIATRICS United States ✓ ACAD PSYCHIATR ACADEMIC PSYCHIATRY United States ✓ ACAD RADIOL ACADEMIC RADIOLOGY United States ✓ ACAD MANAG ANN ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT ANNALS United States ✓ ACAD MANAGE J ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT JOURNAL United States ✓ ACAD MANAG LEARN EDU ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT LEARNING & EDUCATION United States ✓ ACAD MANAGE PERSPECT ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT PERSPECTIVES United States ✓ ACAD MANAGE REV ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT REVIEW United States ✓ ACAROLOGIA ACAROLOGIA France ✓ -

9Th International Congress of Dipterology

9th International Congress of Dipterology Abstracts Volume 25–30 November 2018 Windhoek Namibia Organising Committee: Ashley H. Kirk-Spriggs (Chair) Burgert Muller Mary Kirk-Spriggs Gillian Maggs-Kölling Kenneth Uiseb Seth Eiseb Michael Osae Sunday Ekesi Candice-Lee Lyons Edited by: Ashley H. Kirk-Spriggs Burgert Muller 9th International Congress of Dipterology 25–30 November 2018 Windhoek, Namibia Abstract Volume Edited by: Ashley H. Kirk-Spriggs & Burgert S. Muller Namibian Ministry of Environment and Tourism Organising Committee Ashley H. Kirk-Spriggs (Chair) Burgert Muller Mary Kirk-Spriggs Gillian Maggs-Kölling Kenneth Uiseb Seth Eiseb Michael Osae Sunday Ekesi Candice-Lee Lyons Published by the International Congresses of Dipterology, © 2018. Printed by John Meinert Printers, Windhoek, Namibia. ISBN: 978-1-86847-181-2 Suggested citation: Adams, Z.J. & Pont, A.C. 2018. In celebration of Roger Ward Crosskey (1930–2017) – a life well spent. In: Kirk-Spriggs, A.H. & Muller, B.S., eds, Abstracts volume. 9th International Congress of Dipterology, 25–30 November 2018, Windhoek, Namibia. International Congresses of Dipterology, Windhoek, p. 2. [Abstract]. Front cover image: Tray of micro-pinned flies from the Democratic Republic of Congo (photograph © K. Panne coucke). Cover design: Craig Barlow (previously National Museum, Bloemfontein). Disclaimer: Following recommendations of the various nomenclatorial codes, this volume is not issued for the purposes of the public and scientific record, or for the purposes of taxonomic nomenclature, and as such, is not published in the meaning of the various codes. Thus, any nomenclatural act contained herein (e.g., new combinations, new names, etc.), does not enter biological nomenclature or pre-empt publication in another work.