The Case of Tibet 35

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Knowledge and Belief in the Dialogue of Cultures: Russian Philosophical

Cultural Heritage and Contemporary Change Series IVA, Eastern and Central Europe, Volume 39 General Editor George F. McLean Knowledge and Belief in the Dialogue of Cultures Edited by Marietta Stepanyants Institute of Philosophy, Russian Academy of Sciences The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy Copyright © 2011 by The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy Box 261 Cardinal Station Washington, D.C. 20064 All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Knowledge and belief in the dialogue of cultures / edited by Marietta Stepanyants. p. cm. – (Cultural heritage and contemporary change. Series IVA, Eastern and Central Europe ; v. 39) Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Knowledge, Theory of. 2. Belief and doubt. 3. Faith. 4. Religions. I. Stepaniants, M. T. (Marietta Tigranovna) BD161.K565 2009 2009011488 210–dc22 CIP ISBN 978-1-56518-262-2 (paper) TABLE OF CONTENTS Dedication v George F. McLean Introduction 1 Marietta Stepanyants Part I. Chinese Thought Chapter I. On Knowing (Zhi): Praxis-Guiding Discourse in 17 the Confucian Analects Henry Rosemont, Jr.. Chapter II. Knowledge/Rationale and Belief/Trustiness in 25 Chinese Philosophy Artiom I. Kobzev Chapter III. Two Kinds of Warrant: A Confucian Response to 55 Plantinga’s Theory of the Knowledge of the Ultimate Peimin Ni Chapter IV. Knowledge as Addiction: A Comparative Analysis 59 Hans-Georg Moeller Part II. Indian Thought Chapter V. Alethic Knowledge: The Basic Features of Classical 71 Indian Epistemology, with Some Comparative Remarks on the Chinese Tradition Chakravarthi Ram-Prasad Chapter VI. The Status of the Veda in the Two Mimansas 89 Michel Hulin Chapter VII. -

October 2020 DAVID J. SCHEFFER 25 Mountain Top Road, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87595-9069 Mobile Phone: 708-497-0478; Email: [email protected]

October 2020 DAVID J. SCHEFFER 25 Mountain Top Road, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87595-9069 Mobile phone: 708-497-0478; Email: [email protected] ACADEMIC Clinical Professor Emeritus, Director Emeritus of the Center for International Human Rights, Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law, Sept. 2020-present. Global Law Professor (Spring 2021), KU Leuven University, Belgium. Int’l Criminal Tribunals. Mayer Brown/Robert A. Helman Professor of Law, 2006-2020, Visiting Professor of Law, 2005-2006, and Director of the Center for International Human Rights (2006-2019), Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law. Int’l Human Rights Law, Int’l Criminal Law, Corporate Social Responsibility, Human Rights in Transitional Democracies. DistinguisheD Guest Lecturer, International Law Summer Study Abroad Program of Thomas Jefferson School of Law (San Diego) and the University of Nice School of Law (France), Nice, France, July 2011. Lectures on international criminal law and corporate social responsibility. Faculty Member, The Summer Institute for Global Justice, University of Utrecht, The Netherlands, Summer 2005 (jointly administered by the Washington University School of Law (St. Louis) and Case Western Reserve University School of Law). Course instruction: Atrocity Law and Policy. Visiting Professor of Law, The George Washington University Law School, 2004-2005. Int’l Law I, Int’l Organizations Law, Int’l Criminal Law. Visiting Professor of Law, Georgetown University Law Center, 2003-2004. Int’l Law I, Int’l Institutions Law, Atrocity Law Seminar. Int’l Law I in GULC’s summer program at University College, Faculty of Laws, London (July-Aug. 2004). Visiting Lecturer, National University of Ireland (Galway), July 2003. -

Russia's Activities in Latin America

RUSSIA’S ACTIVITIES IN LATIN AMERICA May 2021 The following is a summary of open-source media reporting on Russia’s presence and activities in Latin America and the Caribbean in May 2021. This is not a complete list of media reports on Russia’s activities in Latin America but are some of the most relevant articles and reports selected by SFS researchers and fellows. The monitor does source a limited amount of media reports from state-owned or -controlled media outlets, which are carefully selected and solely intended to report on news that is not reported on by other media and is relevant for understanding VRIC influence in the region. This report is produced as part of our VRIC Monitor published monthly by the Center for a Secure Free Society (SFS), a non-profit, national security think tank based in Washington D.C. ● According to information circulating on social networks, the leaders Vladimir Putin of Russia and Xi Jinping of China will visit President Nayib Bukele in El Salvador. - Radio YSKL on 21-MAY (content in Spanish) ● State media reports El Salvador is very keen to bolster cooperation with Russia, President Nayib Bukele said during the presentation of the letter of credence ceremony. “We are very enthusiastic about strengthening the relationship with Russia, we are facing a world with new challenges and opportunities, and we want to take advantage of those opportunities,” Bukele told Russian Ambassador Alexander Khokholikov, adding that El Salvador recognizes “the importance of Russia in the world.” - Urdu Point on 20-MAY www.SecureFreeSociety.org © 2021 Center for a Secure Free Society. -

World Book Kids, a New Addition to the World Book Online Reference Center, Is Designed Especially for Younger Users, English-Language Learners, and Reluctant Readers

PUBLIC LIBRARY ASSOCIATION VOLUME 46 • NUMBER 1 • JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2007 ISSN 0163-5506 DEPARTMENTS 4 News from PLA hhes 5 On the Agenda 7 From the President ssan hildreth 15 Tales from the Front jennifer t. ries- FEATURES 17 Perspectives 40 Right-Sizing the Reference Collection nann blaine hilyard The authors detail a large and busy public library branch’s 23 Book Talk method for weeding the reference collection and interfiling it with lisa richter circulating material. rose m. frase and barbara salit-mischel 28 Internet Spotlight lisa ble, nicole 45 KnowItNow heintzelman, steven Ohio’s Virtual Reference Service kronen, and joyce ward Ohio’s virtual reference service, KnowItNow24X7, is a world leader in real-time online reference, with more than 175,000 questions 32 Bringing in the Money answered to date. Now in its third year of operation, its success is erdin due to the collaborative efforts of the three managing libraries and the support of the Ohio Library community. 36 Passing Notes holly carroll, brian leszcz, kristen pool, and tracy strobel michael arrett 54 Going Mobile 74 By the Book The KCLS Roving Reference Model jlie Why wait for patrons to approach the desk? Shouldn’t staff seek out and serve customer’s information needs anywhere in the building? 76 New Product News This article shows how the King County (Wash.) Library System vicki nestin implemented Roving Reference in order to provide the best possible customer service to its patrons. EXTRAS barbara pitney and nancy slote 2 Readers Respond 69 Reference Desk Realities 2 Editor’s Note What they didn’t teach you in library school—Decker Smith and 10 Verso—The Future of Reference Johnson’s practical article aims to help equip librarians for the reali- 13 Verso—By the Numbers ties of day-to-day public library reference work. -

RELS 115.01 Religion & Society in India & Tibet ECTR 219 @ 5:30-6

RELS 115.01 Religion & Society in India & Tibet ECTR 219 @ 5:30-6:45 pm Fall 2016 Dr. Zeff Bjerken Office: RELS bldg. entrance from 4 Glebe St, room 202 Dept of Religious Studies Office hours: Mon & Wed 10-12 pm & by appointment E-mail: [email protected] Phone: 953-7156 Course Description This course is an introduction to two Asian religious traditions, Hinduism & Buddhism, and how they have shaped Indian and Tibetan culture. We will survey forms of social organization (e.g. the caste system, the religious roles of women, monastic life), and the practices and beliefs of Hindus & Buddhists, including their origin myths, rites of passage, and their ethical values. The course is designed around major conceptual themes: discerning between illusion and reality; spiritual journeys in search of religious experience; death and the afterlife; religion, gender, and sexuality; monasticism, asceticism, and the hermit’s life; and the effects of colonialism and modernity on religions. In particular we will examine the religious and political reforms of Mahatma Gandhi and the Dalai Lama, two of the most important leaders of the last century. The non-violent ideals of Gandhi and the Dalai Lama present us with an alternative to our modern consumer-oriented technological culture, where people seek what they are programmed to seek. This course will help you become more informed and critical of how the news media represents other religions and their role in different societies, rather than be passive consumers of the media. You will learn to really “Think Different,” as the Apple advertising campaign once put it (see p. -

Combating Russian Disinformation in Ukraine: Case Studies in a Market for Loyalties

COMBATING RUSSIAN DISINFORMATION IN UKRAINE: CASE STUDIES IN A MARKET FOR LOYALTIES Monroe E. Price* & Adam P. Barry** I. INTRODUCTION This essay takes an oblique approach to the discussion of “fake news.” The approach is oblique geographically because it is not a discourse about fake news that emerges from the more frequently invoked cases centered on the United States and Western Europe, but instead relates primarily to Ukraine. It concerns the geopolitics of propaganda and associated practices of manipulation, heightened persuasion, deception, and the use of available techniques. This essay is also oblique in its approach because it deviates from the largely definitional approach – what is and what is not fake news – to the structural approach. Here, we take a leaf from the work of the (not-so) “new institutionalists,” particularly those who have studied what might be called the sociology of decision-making concerning regulations.1 This essay hypothesizes that studying modes of organizing social policy discourse ultimately can reveal or predict a great deal about the resulting policy outcomes, certainly supplementing a legal or similar analysis. Developing this form of analysis may be particularly important as societies seek to come to grips with the phenomena lumped together under the broad rubric of fake news. The process by which stakeholders assemble to determine a collective position will likely have major consequences for the * Monroe E. Price is an Adjunct Full Professor at the Annenberg School for Communication and the Joseph and Sadie Danciger Professor of Law at Cardozo School of Law. He directs the Stanhope Centre for Communications Policy Research in London, and is the Chair of the Center for Media and Communication Studies of the Central European University in Budapest.” ** Adam P. -

Tibetan Aid Project Pelgrimage Reis 2020 Naar Oost Tibet

Tibetan Aid Project Pelgrimage Reis 2020 naar Oost Tibet Met TAP naar Oost Tibet (Kham) Het Tibetan Aid Project (TAP) organiseert in 2020 van 9 t/m 27 juni weer een pelgrimage reis, dit keer naar de regio Kham in Oost Tibet. Oost Tibet kent een andere historie dan het meer bekende, en ook meer toeristische, Centraal Tibet rondom Lhasa. In de negende en tiende eeuw toen Boeddhisme in Centraal Tibet werd vervolgd, fungeerde Oost Tibet als een toevluchtsoord voor monniken en leraren en werden daar vele teksten veiliggesteld. Veel latere, nu nog bekende, grote meesters vonden juist hier hun thuis in de ontstane kloosters, waar ze studeerden en onderricht gaven. De reis wordt, met programma inbreng van TAP, op maat voor ons georganiseerd en begeleid door Visit Travel Tibet Service. Dit is dezelfde organisatie waarmee we tot volle tevredenheid in eerdere jaren naar Centraal Tibet zijn geweest. Het Tibetan Aid Project fungeert hiervoor enkel als intermediair. We besteden in deze reis vooral aandacht aan de boeddhistische tempels en kloosters. Maar ook aan het landschap en de natuur van dit andere deel van Tibet met zijn groene heuvels, bossen, imposante bergen, woeste rivieren, diepe valleien en gletsjermeren. 1 Programma algemeen Het programma is onder voorbehoud van gewijzigde omstandigheden. Zo mogelijk en in overleg met onze Tibetaanse gids kan soms ook op verzoek besloten worden tot wijzigingen in het programma. De afstanden die we afleggen zijn groter dan in Centraal Tibet, waardoor we per dag vaak 2 tot 3 uur reizen, een enkele keer 6 – 7 uur op weg naar een volgende regio. -

A Distant Mirror. Articulating Indic Ideas in Sixth and Seventh Century

Index pp. 535–565 in: Chen-kuo Lin / Michael Radich (eds.) A Distant Mirror Articulating Indic Ideas in Sixth and Seventh Century Chinese Buddhism Hamburg Buddhist Studies, 3 Hamburg: Hamburg University Press 2014 Imprint Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (German National Library). The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de. The online version is available online for free on the website of Hamburg University Press (open access). The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek stores this online publication on its Archive Server. The Archive Server is part of the deposit system for long-term availability of digital publications. Available open access in the Internet at: Hamburg University Press – http://hup.sub.uni-hamburg.de Persistent URL: http://hup.sub.uni-hamburg.de/purl/HamburgUP_HBS03_LinRadich URN: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn/resolver.pl?urn:nbn:de:gbv:18-3-1467 Archive Server of the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek – http://dnb.d-nb.de ISBN 978-3-943423-19-8 (print) ISSN 2190-6769 (print) © 2014 Hamburg University Press, Publishing house of the Hamburg State and University Library Carl von Ossietzky, Germany Printing house: Elbe-Werkstätten GmbH, Hamburg, Germany http://www.elbe-werkstaetten.de/ Cover design: Julia Wrage, Hamburg Contents Foreword 9 Michael Zimmermann Acknowledgements 13 Introduction 15 Michael Radich and Chen-kuo Lin Chinese Translations of Pratyakṣa 33 Funayama Toru -

C:\Users\Kusala\Documents\2009 Buddhist Center Update

California Buddhist Centers / Updated August 2009 Source - www.Dharmanet.net Abhayagiri Buddhist Monastery Address: 16201 Tomki Road, Redwood Valley, CA 95470 CA Tradition: Theravada Forest Sangha Affiliation: Amaravati Buddhist Monastery (UK) EMail: [email protected] Website: http://www.abhayagiri.org All One Dharma Address: 1440 Harvard Street, Quaker House Santa Monica CA 90404 Tradition: Non-Sectarian, Zen/Vipassana Affiliation: General Buddhism Phone: e-mail only EMail: [email protected] Website: http://www.allonedharma.org Spiritual Director: Group effort Teachers: Group lay people Notes and Events: American Buddhist Meditation Temple Address: 2580 Interlake Road, Bradley, CA 93426 CA Tradition: Theravada, Thai, Maha Nikaya Affiliation: Thai Bhikkhus Council of USA American Buddhist Seminary Temple at Sacramento Address: 423 Glide Avenue, West Sacramento CA 95691 CA Tradition: Theravada EMail: [email protected] Website: http://www.middleway.net Teachers: Venerable T. Shantha, Venerable O.Pannasara Spiritual Director: Venerable (Bhante) Madawala Seelawimala Mahathera American Young Buddhist Association Address: 3456 Glenmark Drive, Hacienda Heights, CA 91745 CA Tradition: Mahayana, Humanistic Buddhism Contact: Vice-secretary General: Ven. Hui-Chuang Amida Society Address: 5918 Cloverly Avenue, Temple City, CA 91780 CA Tradition: Mahayana, Pure Land Buddhism EMail: [email protected] Spiritual Director: Ven. Master Chin Kung Amitabha Buddhist Discussion Group of Monterey Address: CA Tradition: Mahayana, Pure Land Buddhism Affiliation: Bodhi Monastery Phone: (831) 372-7243 EMail: [email protected] Spiritual Director: Ven. Master Chin Chieh Contact: Chang, Ei-Wen Amitabha Buddhist Society of U.S.A. Address: 650 S. Bernardo Avenue, Sunnyvale, CA 94087 CA Tradition: Mahayana, Pure Land Buddhism EMail: [email protected] Spiritual Director: Ven. -

Buddhism and the Global Bazaar in Bodh Gaya, Bihar

DESTINATION ENLIGHTENMENT: BUDDHISM AND THE GLOBAL BAZAAR IN BODH GAYA, BIHAR by David Geary B.A., Simon Fraser University, 1999 M.A., Carleton University, 2003 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Anthropology) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) December 2009 © David Geary, 2009 ABSTRACT This dissertation is a historical ethnography that examines the social transformation of Bodh Gaya into a World Heritage site. On June 26, 2002, the Mahabodhi Temple Complex at Bodh Gaya was formally inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List. As a place of cultural heritage and a monument of “outstanding universal value” this inclusion has reinforced the ancient significance of Bodh Gaya as the place of Buddha's enlightenment. In this dissertation, I take this recent event as a framing device for my historical and ethnographic analysis that details the varying ways in which Bodh Gaya is constructed out of a particular set of social relations. How do different groups attach meaning to Bodh Gaya's space and negotiate the multiple claims and memories embedded in place? How is Bodh Gaya socially constructed as a global site of memory and how do contests over its spatiality im- plicate divergent histories, narratives and events? In order to delineate the various historical and spatial meanings that place holds for different groups I examine a set of interrelated transnational processes that are the focus of this dissertation: 1) the emergence of Buddhist monasteries, temples and/or guest houses tied to international pilgrimage; 2) the role of tourism and pilgrimage as a source of economic livelihood for local residents; and 3) the role of state tourism development and urban planning. -

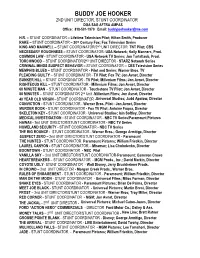

BUDDY JOE HOOKER 2ND UNIT DIRECTOR, STUNT COORDINATOR DGA SAG AFTRA AMPAS Office: 818-501-1970 Email: [email protected]

BUDDY JOE HOOKER 2ND UNIT DIRECTOR, STUNT COORDINATOR DGA SAG AFTRA AMPAS Office: 818-501-1970 Email: [email protected] H.R. – STUNT COORDINATOR – Lifetime Television Pilot; Hilton Smith, Producer RAKE – STUNT COORDINATOR – 20th Century Fox; Fox Television Series KING AND MAXWELL – STUNT COORDINATOR/2ND UNIT DIRECTOR TNT Pilot; CBS NECESSARY ROUGHNESS – STUNT COORDINATOR- USA Network; Kelly Manners, Prod. COMMON LAW - STUNT COORDINATOR - USA Network TV Series; Jon Turteltaub, Prod. TORCHWOOD – STUNT COORDINATOR/2ND UNIT DIRECTOR - STARZ Network Series CRIMINAL MINDS SUSPECT BEHAVIOR – STUNT COORDINATOR -- CBS Television Series MEMPHIS BLUES – STUNT COORDINATOR - Pilot and Series; Warner Bros. TV PLEADING GUILTY – STUNT COORDINATOR - TV Pilot; Fox TV; Jon Avnet, Director BUNKER HILL – STUNT COORDINATOR - TV Pilot; Millenium Films; Jon Avnet, Director RIGHTEOUS KILL – STUNT COORDINATOR - Millenium Films; Jon Avnet, Director 60 MINUTE MAN – STUNT COORDINATOR - Touchstone TV Pilot; Jon Avnet, Director 88 MINUTES – STUNT COORDINATOR 2nd Unit -Millenium Films; Jon Avnet, Director 40 YEAR OLD VIRGIN - STUNT COORDINATOR -Universal Studios; Judd Apatow, Director CONVICTION - STUNT COORDINATOR - Warner Bros. Pilot - Jon Avnet, Director MURDER BOOK - STUNT COORDINATOR - Fox TV Pilot; Antoine Fuqua, Director SKELETON KEY - STUNT COORDINATOR - Universal Studios; Iain Softley, Director MEDICAL INVESTIGATION - STUNT COORDINATOR - NBC TV Series/Paramount Pictures HAWAII - 2nd UNIT DIRECTOR/STUNT COORDINATOR - NBC TV Series HOMELAND SECURITY - STUNT -

Tibetan Yoga: a Complete Guide to Health and Wellbeing Pdf, Epub, Ebook

KUM MYE : TIBETAN YOGA: A COMPLETE GUIDE TO HEALTH AND WELLBEING PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Tarthang Tulku | 424 pages | 30 Apr 2007 | Dharma Publishing,U.S. | 9780898004212 | English | Berkeley, United States Kum Mye : Tibetan Yoga: a Complete Guide to Health and Wellbeing PDF Book Product Details About the Author. We develop our own language to explore feeling, dropping the labels and stories we might have attached to our vast array of feeling, and watching as they expand and flow. History Timeline Outline Culture Index of articles. Having established a foundation of calmness, we are ready to experience the unique tonal quality of all of the sensations in the body, and begin to explore the relationship between 'inner' and 'outer. The foundation of Kum Nye is deep relaxation, first at the physical level of tension, and then at the level of tension between us and the world around us, and finally, at the level of tension between our individual purpose and the flow of life. Sign in to Purchase Instantly. Practices and attainment. Thoughts on transmission : knowingness transforms causal conditions 2 copies. Tanya Roberts' publicist says she is not dead. Its benefits are said to include elimination of toxins, increased vitality, pain reduction, and calming of nervous disorders including insomnia, depression and anxiety. Skillful Means copies. People might be disappointed by the paucity of exertion during a Kum Nye practice, but then surprised by the depth of relaxation after a session. No events listed. In he moved to the United States where he has lived and worked ever since. Like this: Like Loading Uh-oh, it looks like your Internet Explorer is out of date.