Local Identities Global Challenges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shifting Shopping Patterns Through Food Marketplace Platform: a Case Study in Major Cities of Indonesia

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 31 May 2021 doi:10.20944/preprints202105.0718.v1 Article SHIFTING SHOPPING PATTERNS THROUGH FOOD MARKETPLACE PLATFORM: A CASE STUDY IN MAJOR CITIES OF INDONESIA 1 2 3 Istianingsih * Islamiah Kamil robertus Suraji 1 Economics and Business Faculty, Universitas Bhayangkara Jakarta Raya, Kota Jakarta Selatan, Daerah Khusus Ibukota Jakarta 12550, Indonesia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] 2 Business and Social Science Faculty, Universitas Dian Nusantara. [email protected] 2 Computer Science Faculty, Universitas Bhayangkara Jakarta Raya, Kota Jakarta Selatan, Daerah Khusus Ibukota Jakarta 12550, Indonesia; [email protected] Abstract: The obligation to keep a distance from other people due to the pandemic has changed human life patterns, especially in shopping for their primary needs, namely food. The presence of the food marketplace presents new hope in maintaining health and food availability without crowding with other people while shopping. The main problem that is often a concern of the public when shopping online is transaction security and the Ease of use of this food marketplace applica- tion. This research is the intensity of using the Food Marketplace in terms of Interest, transaction security, and Ease of use of this application.Researchers analyzed the relationship between varia- bles with the Structural equation model. Respondents who became this sample were 300 applica- tion users spread across various major cities in Indonesia.This study's results provide a view that the intensity of the food marketplace's use has increased significantly during the new normal life. -

Taking the Borough Market Route: an Experimental Ethnography of the Marketplace

Taking the Borough Market Route: An Experimental Ethnography of the Marketplace Freek Janssens -- 0303011 Freek.Janssens©student.uva.nl June 2, 2008 Master's thesis in Cultural An thropology at the Universiteit van Amsterdam. Committee: dr. Vincent de Rooij (supervi sor), prof. dr. Johannes Fabian and dr. Gerd Baumann. The River Tharrws and the Ciiy so close; ihis mnst be an important place. With a confident but at ihe same time 1incertain feeling, I walk thrmigh the large iron gales with the golden words 'Borough Market' above il. Asphalt on the floor. The asphalt seems not to correspond to the classical golden letters above the gate. On the right, I see a painted statement on the wall by lhe market's .mpcrintendent. The road I am on is private, it says, and only on market days am [ allowed here. I look around - no market to sec. Still, I have lo pa8s these gales to my research, becanse I am s·upposed to meet a certain Jon hCTe today, a trader at the market. With all the stories I had heard abont Borongh Market in my head, 1 get confnsed. There is nothing more to see than green gates and stalls covered with blue plastic sheets behind them. I wonder if this can really turn into a lively and extremely popular market during the weekend. In the corner I sec a sign: 'Information Centre. ' There is nobody. Except from some pigeons, all I see is grey walls, a dirty roof, gates, closed stalls and waste. Then I see Jon. A man in his forties, small and not very thin, walks to me. -

Lumen De Lumine the NEWSLETTER of the MANILA OBSERVATORY

Lumen de Lumine THE NEWSLETTER OF THE MANILA OBSERVATORY Vol.1 Issue No. 2 | July-September 2018 What’s Inside University of Arizona Scientists visit Manila Observatory INSTRUMENT SET-UP–– Dr. Armin Sorooshian and three Lecture Series: of his PhD students, Alexis McDonald, Connor Stahl, and Aerosol Physics and Rachel Braun, from the University of Arizona visited the Manila Chemistry 2 Observatory last 17 July-01 August ahead of the implementation of the Cloud, Aerosols and Monsoon Processes Philippines Coastal Cities at Risk Experiment (CAMP2Ex) in 2019. Holds First National Conference 2 Dr. Sorooshian’s visit marked the beginning of CHECSM (CAMP2Ex Weather and Composition Monitoring), which is an National and intensive field campaign as a prelude to CAMP2Ex. International Participation The team from the University of Arizona set-up a micro-orifice uniform deposit impactor (MOUDI) at the Annex Building of Dr. Gemma Narisma the Manila Observatory. MOUDI presents a 12-stage cascade Gives Talk on Space- impactor that can segregate ultra-fine, fine, and coarse particulate Based information matter. The Observatory is classified as an urban-mix site which for Understanding will be able to paint a picture of aerosol characteristics coming Atmospheric Hazards from different sources. in Disaster Risk TOP: MOUDI Set-up at the Manila Observatory’s Annex Building 3 BOTTOM: UofA Researchers explain MOUDI to AQD-ITD and MO Data gathered in CHECSM will serve as a baseline measurement Staff (Photos from AQD-ITD) Regional Climate in an urban environment. MOUDI is set to measure air quality for Systems Laboratory in one year in the Observatory Grounds. -

Unlocking Potential What’S in This Report

Great Portland Estates plc Annual Report 2013 Unlocking potential What’s in this report 1. Overview 3. Financials 1 Who we are 68 Group income statement 2 What we do 68 Group statement of comprehensive income 4 How we deliver shareholder value 69 Group balance sheet 70 Group statement of cash flows 71 Group statement of changes in equity 72 Notes forming part of the Group financial statements 93 Independent auditor’s report 95 Wigmore Street, W1 94 Company balance sheet – UK GAAP See more on pages 16 and 17 95 Notes forming part of the Company financial statements 97 Company independent auditor’s report 2. Annual review 24 Chairman’s statement 4. Governance 25 Our market 100 Corporate governance 28 Valuation 113 Directors’ remuneration report 30 Investment management 128 Report of the directors 32 Development management 132 Directors’ responsibilities statement 34 Asset management 133 Analysis of ordinary shareholdings 36 Financial management 134 Notice of meeting 38 Joint ventures 39 Our financial results 5. Other information 42 Portfolio statistics 43 Our properties 136 Glossary 46 Board of Directors 137 Five year record 48 Our people 138 Financial calendar 52 Risk management 139 Shareholders’ information 56 Our approach to sustainability “Our focused business model and the disciplined execution of our strategic priorities has again delivered property and shareholder returns well ahead of our benchmarks. Martin Scicluna Chairman ” www.gpe.co.uk Great Portland Estates Annual Report 2013 Section 1 Overview Who we are Great Portland Estates is a central London property investment and development company owning over £2.3 billion of real estate. -

Mandaluyong City, Philippines

MANDALUYONG CITY, PHILIPPINES Case Study (Public Buildings) Project Summary: Manila, the capital of the Republic of the Philippines, has the eighteenth largest metropolitan area in the world, which includes fifteen cities and two municipalities. Mandaluyong City is the smallest city of the cities in Metro Manila, with an area of only twelve square kilometers and a population of over 278,000 people. A public market was located in the heart of Mandaluyong City, on a 7,500 square meters area along Kalentong Road, a main transit route. In 1991, the market was destroyed in a major fire, in large part because most of the structure was made of wood. As a temporary answer for the displaced vendors, the government allowed about 500 of them to set up stalls along the area’s roads and sidewalks. This rapidly proved to be impractical, in that it led to both traffic congestion and sanitation problems. Rebuilding the public market became a high priority for the city government, but financing a project with an estimated cost of P50 million was beyond the city’s capability. Local interest rates were high, averaging approximately 18 percent annually, and the city was not prepared to take on the additional debt that construction of a new market would have required. The city government was also concerned that if the charges to stall owners became too onerous, the increased costs would have to be passed on to their customers, many of whom were lower-income residents of the area. The answer to this problem that the city government decided to utilize was based on the Philippines’ national Build-Operate-Transfer law of 1991. -

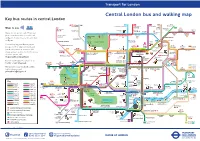

Central London Bus and Walking Map Key Bus Routes in Central London

General A3 Leaflet v2 23/07/2015 10:49 Page 1 Transport for London Central London bus and walking map Key bus routes in central London Stoke West 139 24 C2 390 43 Hampstead to Hampstead Heath to Parliament to Archway to Newington Ways to pay 23 Hill Fields Friern 73 Westbourne Barnet Newington Kentish Green Dalston Clapton Park Abbey Road Camden Lock Pond Market Town York Way Junction The Zoo Agar Grove Caledonian Buses do not accept cash. Please use Road Mildmay Hackney 38 Camden Park Central your contactless debit or credit card Ladbroke Grove ZSL Camden Town Road SainsburyÕs LordÕs Cricket London Ground Zoo Essex Road or Oyster. Contactless is the same fare Lisson Grove Albany Street for The Zoo Mornington 274 Islington Angel as Oyster. Ladbroke Grove Sherlock London Holmes RegentÕs Park Crescent Canal Museum Museum You can top up your Oyster pay as Westbourne Grove Madame St John KingÕs TussaudÕs Street Bethnal 8 to Bow you go credit or buy Travelcards and Euston Cross SadlerÕs Wells Old Street Church 205 Telecom Theatre Green bus & tram passes at around 4,000 Marylebone Tower 14 Charles Dickens Old Ford Paddington Museum shops across London. For the locations Great Warren Street 10 Barbican Shoreditch 453 74 Baker Street and and Euston Square St Pancras Portland International 59 Centre High Street of these, please visit Gloucester Place Street Edgware Road Moorgate 11 PollockÕs 188 TheobaldÕs 23 tfl.gov.uk/ticketstopfinder Toy Museum 159 Russell Road Marble Museum Goodge Street Square For live travel updates, follow us on Arch British -

Hexagon-Apartments-Brochure.Pdf

A contemporary collection of brand new, luxury residences in the heart of London’s Covent Garden, comprising 15 floors of outstanding one, two and three bedroom apartments and penthouses. An iconic building rising far above the neighbouring rooftops, designed by world-renowned architects Squire & Partners, with interior specification by leading designers Michaelis Boyd. Residents will benefit from a tailored concierge service by Qube, that will offer a full range of lifestyle management options for a seamless living experience. HEXAGON APARTMENTS PENTHOUSE VIEW SIX UNRIVALLED VIEWS, ONE REMARKABLE BUILDING Uninterrupted views of Prime Central London’s distinguished skyline, protected through 360° by the surrounding Seven Dials Conservation Area. 2 3 HEXAGON APARTMENTS EXCEPTIONAL INTERIORS Each residence at Hexagon Apartments has been crafted to a contemporary design finish, by interiors specialists Michaelis Boyd, that resonates with the building’s arresting architectural style. Exposed structural columns, polished concrete kitchen surfaces and delicate metal-framed internal glazing complement the geometric form of the tower, and perfectly balance luxury details such as chevron timber flooring and bespoke joinery. Floor-to-ceiling windows inside each apartment create beautiful and light-filled living spaces. 4 5 HEXAGON APARTMENTS EXCEPTIONAL INTERIORS 6 7 HEXAGON APARTMENTS PENTHOUSE TERRACES 8 9 HEXAGON APARTMENTS THE LONDON LANDMARKS The Hexagon Apartments are located at the heart of London’s Covent Garden, in close proximity to the -

353-THE-STRAND-BROCHURE.Pdf

INTRODUCTION 353 The Strand is a striking period property situated on the northeast corner of this world famous address. Four individually appointed apartments make up this boutique residence in London’s Covent Garden. The property’s stone façade echoes the beauty of the adjacent Somerset House and the luxurious interiors are designed with meticulous attention to detail. Three lateral apartments grace the first, second and third floors, whilst a duplex penthouse occupies the fourth and fifth. All benefit from at least one balcony or roof terrace, as well as far reaching views down Lancaster Place towards the River Thames and the South Bank. 3 BATTERSEA POWER STATION BIG BEN LONDON ST JAMES’S EYE PALACE HOUSES OF PARliAMENT BUCKINGHAM PALACE ST JAMES’S PARK DOWNING WESTMINSTER STREET BRIDGE THE MALL LOCATION ROYAL HORSE GUARDS PARADE JUbilEE PALL MALL GARDENS Located only a stone’s throw from the Covent Garden TRAFALGAR SQUARE Piazza, 353 The Strand is perfectly positioned CHARING for all that Central London has to offer. CROss VICTORIA NATIONAL EMBANKMENT GALLERY GARDENS Covent Garden, with its bustling Piazza, forms London’s LEicESTER cultural heartland which is serviced by extensive transport SQUARE links. The surrounding area has a diverse restaurant offering and unparalleled retailing. With the world famous Royal Opera House, thirteen historic theatres and an array of fine restaurants, this enclave of central London is a vibrant place to live. STRAND With the West End on the door step and the entrance to the APPROXIMATE DISTANCES City of London just half a mile away, the Capital’s principal business TO POPULAR DESTINATIONS districts and educational campuses are all within convenient reach. -

Seven Dials Guidelines

Conservation area statement Seven Dials (Covent Garden) 7 Newman Street Street Queen Great akrStreet Parker Theatre London tklyStreet Stukeley New aki Street Macklin Drury Lane This way up for map etro Street Betterton Endell St hrsGardens Shorts Neal Street Theatre Cambridge ala Street Earlham Mercer Street omuhStreet Monmouth Dials page 3 Location Seven page 6 History page 10 Character page 19 Audit Tower Street page 26 Guidelines West Street hfebr Avenue Shaftesbury SEVEN DIALS (Covent Garden) Conservation Area Statement The aim of this Statement is to provide a clear indication of the Council’s approach to the preservation and enhancement of the Seven Dials (Covent Garden) Conservation Area. The Statement is for the use of local residents, community groups, businesses, property owners, architects and developers as an aid to the formulation and design of development proposals and change in the area. The Statement will be used by the Council in the assessment of all development proposals. Camden has a duty under the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990 to designate as conservation areas any “areas of special architectural or historic interest, the character or historic interest of which it is desirable to preserve.” Designation provides the basis for policies designed to preserve or enhance the special interest of such an area. Designation also introduces a general control over the demolition of unlisted buildings. The Council’s policies and guidance for conservation areas are contained in the Unitary Development Plan (UDP) and Supplementary Planning Guidance (SPG). This Statement is part of SPG and gives additional detailed guidance in support of UDP policies. -

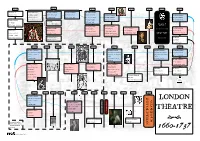

An A2 Timeline of the London Stage Between 1660 and 1737

1660-61 1659-60 1661-62 1662-63 1663-64 1664-65 1665-66 1666-67 William Beeston The United Company The Duke’s Company The Duke’s Company The Duke’s Company @ Salisbury Court Sir William Davenant Sir William Davenant Sir William Davenant Sir William Davenant The Duke’s Company The Duke’s Company & Thomas Killigrew @ Salisbury Court @Lincoln’s Inn Fields @ Lincoln’s Inn Fields Sir William Davenant Sir William Davenant Rhodes’s Company @ The Cockpit, Drury Lane @ Red Bull Theatre @ Lincoln’s Inn Fields @ Lincoln’s Inn Fields George Jolly John Rhodes @ Salisbury Court @ The Cockpit, Drury Lane @ The Cockpit, Drury Lane The King’s Company The King’s Company PLAGUE The King’s Company The King’s Company The King’s Company Thomas Killigrew Thomas Killigrew June 1665-October 1666 Anthony Turner Thomas Killigrew Thomas Killigrew Thomas Killigrew @ Vere Street Theatre @ Vere Street Theatre & Edward Shatterell @ Red Bull Theatre @ Bridges Street Theatre @ Bridges Street Theatre @ The Cockpit, Drury Lane @ Bridges Street Theatre, GREAT FIRE @ Red Bull Theatre Drury Lane (from 7/5/1663) The Red Bull Players The Nursery @ The Cockpit, Drury Lane September 1666 @ Red Bull Theatre George Jolly @ Hatton Garden 1676-77 1675-76 1674-75 1673-74 1672-73 1671-72 1670-71 1669-70 1668-69 1667-68 The Duke’s Company The Duke’s Company The Duke’s Company The Duke’s Company Thomas Betterton & William Henry Harrison and Thomas Henry Harrison & Thomas Sir William Davenant Smith for the Davenant Betterton for the Davenant Betterton for the Davenant @ Lincoln’s Inn Fields -

The Workplace Food Hall & the Future of the Company

THE WORKPLACE FOOD HALL & THE FUTURE OF THE COMPANY CAFETERIA Everyone loves great food. Over the past few decades, we’ve gone from a culture that placed a premium on meals of convenience — microwave dinners, fast food, anything that comes out of a box — to one that increasingly values delicious, high-quality food experiences. We no longer settle for whatever is easiest or cheapest. We now live in an age where people will happily drive miles out of their way to grab a gourmet grilled cheese from a food truck with great Yelp reviews. We also crave variety, authenticity, and value in our meals. Present us with a predictable and lackluster menu, and we notice. If the food isn’t great, we probably won’t come back if we have better options. That’s even true for those hurried meals we take during our lunch breaks at work. For legacy cafeteria providers, the consumer shift towards thoughtful, artisanal meals is becoming a serious problem. For legacy cafeteria The Global providers it was never Food Hall Trend about the food The idea behind the modern food hall is simple: Create a central place where people from all walks of life can come Countless companies have spent — and lost — a tremendous together to sample and taste their way through the best amount of money on their cafeterias. They’re losing more dishes an entire city has to offer. It works by turning an now than ever before. The reasons for this aren’t hard to otherwise underused space — often an empty section of a understand. -

Fernando Amorsolo's Marketplace During the Occupation Ms Clarissa

Fernando Amorsolo’s Marketplace during the Occupation Clarissa Chikiamco Curator, National Gallery Singapore 109 Figure 1. Fernando Amorsolo, Marketplace during the Occupation, 1942, oil on canvas, 57 by 82cm. Collection of National Gallery Singapore. World War II was a painful event globally and its events around him, he departed mostly from impact was felt no less in the region of Southeast his usual subject matters of idyllic images of the Asia. Te Japanese Occupation of several countries countryside, such as men and women planting in this part of the world led to innumerable rice, for which he had become well-known. instances of rape, torture and killings. While it was obviously a horrifying period, many artists In 1942, Japanese forces entered Manila, across the region felt compelled to respond – either immediately afer New Year’s Day. Amorsolo by painting during the war and documenting intriguingly chose to paint a market scene that what was happening, or reacting in retrospect frst year of the Japanese Occupation (Figure. 1), afer the war when there was sufcient time, quite diferent from the ruins he painted towards space and safety to re-engage in artistic practice. the end of the war or his theatrical scene of a Singapore’s National Collection encompasses male hero stalwartly defending a woman from various Southeast Asian works which capture rape by a Japanese soldier (Figures. 2 and 3). At the artists’ diferent responses to a shared frst glance, Marketplace during the Occupation historical experience. seemingly depicts a typical market scene, with vendors selling fruits and vegetables to interested Tree of these works are by one of the Philippines’ members of the public.