Antoine De Saint Exupery and the Quest for Truth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Because We Struggle to Survive'

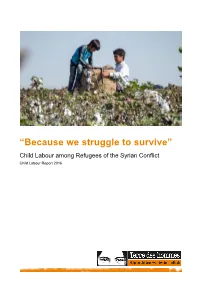

“Because we struggle to survive” Child Labour among Refugees of the Syrian Conflict Child Labour Report 2016 Disclaimer terre des hommes Siège | Hauptsitz | Sede | Headquarters Avenue de Montchoisi 15, CH-1006 Lausanne T +41 58 611 06 66, F +41 58 611 06 77 E-mail : [email protected], CCP : 10-11504-8 Research support: Ornella Barros, Dr. Beate Scherrer, Angela Großmann Authors: Barbara Küppers, Antje Ruhmann Photos : Front cover, S. 13, 37: Servet Dilber S. 3, 8, 12, 21, 22, 24, 27, 47: Ollivier Girard S. 3: Terre des Hommes International Federation S. 3: Christel Kovermann S. 5, 15: Terre des Hommes Netherlands S. 7: Helmut Steinkeller S. 10, 30, 38, 40: Kerem Yucel S. 33: Terre des hommes Italy The study at hand is part of a series published by terre des hommes Germany annually on 12 June, the World Day against Child Labour. We would like to thank terre des hommes Germany for their excellent work, as well as Terre des hommes Italy and Terre des Hommes Netherlands for their contributions to the study. We would also like to thank our employees, especially in the Middle East and in Europe for their contributions to the study itself, as well as to the work of editing and translating it. Terre des hommes (Lausanne) is a member of the Terre des Hommes International Federation (TDHIF) that brings together partner organisations in Switzerland and in other countries. TDHIF repesents its members at an international and European level. First published by terre des hommes Germany in English and German, June 2016. -

LOYALTY in the WORKS of SAINT-EXUPBRY a Thesis

LOYALTY IN THE WORKS OF SAINT-EXUPBRY ,,"!"' A Thesis Presented to The Department of Foreign Languages The Kansas State Teachers College of Emporia In Partial Fulfillment or the Requirements for the Degree Mastar of Science by "., ......, ~:'4.J..ry ~pp ~·.ay 1967 T 1, f" . '1~ '/ Approved for the Major Department -c Approved for the Graduate Council ~cJ,~/ 255060 \0 ACKNOWLEDGMENT The writer wishes to extend her sincere appreciation to Dr. Minnie M. Miller, head of the foreign language department at the Kansas State Teachers College of Emporia, for her valuable assistance during the writing of this thesis. Special thanks also go to Dr. David E. Travis, of the foreign language department, who read the thesis and offered suggestions. M. E. "Q--=.'Hi" '''"'R ? ..... .-.l.... ....... v~ One of Antoine de Saint-Exupe~J's outstanding qualities was loyalty. Born of a deep sense of responsi bility for his fellowmen and a need for spiritual fellow ship with them it became a motivating force in his life. Most of the acts he is remeffibered for are acts of fidelityo Fis writings too radiate this quality. In deep devotion fo~ a cause or a friend his heroes are spurred on to unusual acts of valor and sacrifice. Saint-Exupery's works also reveal the deep movements of a fervent soul. He believed that to develop spiritually man mQst take a stand and act upon his convictions in the f~c0 of adversity. In his boo~ UnSens ~ la Vie, l he wrote: ~e comprenez-vous Das a~e le don de sol, le risque, ... -

Notions of Self and Nation in French Author

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 6-27-2016 Notions of Self and Nation in French Author- Aviators of World War II: From Myth to Ambivalence Christopher Kean University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Kean, Christopher, "Notions of Self and Nation in French Author-Aviators of World War II: From Myth to Ambivalence" (2016). Doctoral Dissertations. 1161. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1161 Notions of Self and Nation in French Author-Aviators of World War II: From Myth to Ambivalence Christopher Steven Kean, PhD University of Connecticut, 2016 The traditional image of wartime aviators in French culture is an idealized, mythical notion that is inextricably linked with an equally idealized and mythical notion of nationhood. The literary works of three French author-aviators from World War II – Antoine de Saint- Exupéry, Jules Roy, and Romain Gary – reveal an image of the aviator and the writer that operates in a zone between reality and imagination. The purpose of this study is to delineate the elements that make up what I propose is a more complex and even ambivalent image of both individual and nation. Through these three works – Pilote de guerre (Flight to Arras), La Vallée heureuse (The Happy Valley), and La Promesse de l’aube (Promise at Dawn) – this dissertation proposes to uncover not only the figures of individual narratives, but also the figures of “a certain idea of France” during a critical period of that country’s history. -

Ar.Itorne DE Sarrvr- Exupf Nv

Ar.itorNE DE Sarrvr-Exupf nv Born: Lyon, France June 29, 1900 Died: Near Corsica July3l ,7944 Throughhis autobiographicalworhs, Saint-Exupery captures therra of earlyaviation uith his$rical prose and ruminations, oftenrnealing deepertruths about the human condition and humanity'ssearch for meaningand fulfillrnar,t. teur" (the aviator), which appeared in the maga- zine LeNauired'Argentin 1926.Thus began many of National Archive s Saint-Exup6ry's writings on flying-a merging of two of his greatestpassions in life. At the time, avia- Brocnaprrv tion was relatively new and still very dangerous. Antoine Jean-Baptiste Marie Roger de Saint- The technology was basic, and many pilots relied Exup6ry (sahn-tayg-zew-pay-REE)rvas born on on intuition. Saint-Exup6ry,however, was drawn to June 29, 1900, in Lyon, France, the third of five the adventure and beauty of flight, which he de- children in an aristocratic family. His father died of picted in many of his works. a stroke lvhen Saint-Exup6ry was only three, and Saint-Exup6rybecame a frontiersman of the sky. his mother moved the family to Le Mans. Saint- He reveled in flying open-cockpit planes and loved Exup6ry, knor,vn as Saint-Ex, led a happy child- the freedom and solitude of being in the air. For hood. He wassurrounded by many relativesand of- three years,he r,vorkedas a pilot for A6ropostale, a ten spent his summer vacations rvith his family at French commercial airline that flew mail. He trav- their chateau in Saint-Maurice-de-Remens. eled berween Toulouse and Dakar, helping to es- Saint-Exup6ry went to Jesuit schools and to a tablish air routes acrossthe African desert. -

Terre Des Hommes – Annual Report 2017

Annual Report 2017 2 terre des hommes – Annual Report 2017 Imprint Contents terre des hommes 3 Greeting Help for Children in Need 4 Report by the Executive Board 6 terre des hommes’ vision Head Office 8 terre des hommes’ programme activities Ruppenkampstraße 11a 49 084 Osnabrück Germany Goals and impacts of our programme activity 10 Participation makes children strong Phone +49 (0) 5 41/71 01-0 13 Creating safe spaces for children Telefax +49 (0) 5 41/70 72 33 16 Children’s right to a healthy environment [email protected] 19 Advocacy for children’s rights www.tdh.de 22 Map of project countries Account of donations BIC NOLADE 22 XXX 28 Quality assurance, monitoring, transparency IBAN DE34 2655 0105 0000 0111 22 30 Risk management 31 The International Federation TDHIF Editorial Staff 32 You change more than you give Wolf-Christian Ramm (editor in charge), 36 The 2017 donation year Tina Böcker-Eden, Michael Heuer, 38 »How far would you go?!« Athanasios Melissis, Iris Stolz 40 terre des hommes spotlights itself Editorial Assistant Cornelia Dernbach Balance 2017 44 terre des hommes in figures Photos Front cover: M. Pelser; p. 3 top, 8, 37: F. Kopp; p. 3 bottom, 50 Outlook and future challenges 14, 19, 27, 33 bottom, 40 top, 52 bottom, 52 m., 53 top: 52 Organisation structure of terre des hommes C. Kovermann / terre des hommes; p. 4: M. Klimek; 54 Organisation chart of terre des hommes p. 7: S. Basu / terre des hommes; p. 11, 21: Kindernothilfe; p. 12: T. Schwab; p. 13: terre des hommes Lausanne; p. -

Communicating for Terre Des Hommes on Social Networks. Impressum

Social Media Toolkit. Communicating for Terre des hommes on social networks. Impressum. Responsible for publication : Yann Graf Production Coodinator : Laure Silacci Translations Coordinator : Lucie Concordel English Translation : Probst German Translation : Anina Kurth Layout : Angélique Bühlmann This guide was edited in 2012 by the communication department of Terre des hommes. It is based on the Social Media Toolkit of the American Red Cross. Please do not hesitate to share your comments with us to help us improve the guide in the future ([email protected]). We would like to sincerely thank Christine Brosteaux, Mylène Ntamatungiro, Joseph Aguetant and Antoine Lissorgues for their help in producing this document. © Tdh / April 2015 – Version 1.1 Summary 1. Introduction 4 2. Section 1 - Definition 5 2.a Understanding social media 5 2.b Managing the risks 7 2.c The reputation of Tdh : Being cautious online 8 2.d The main platforms 9 2.e Before you begin 10 3. Section 2 - Practical guide 13 3.a Getting started on Facebook 13 3.b Getting started on Twitter 18 4. Appendices 23 Social Media Toolkit 3 1. Introduction. With a billion users on Facebook and Twitter, social networks have become indispensable. Internet users spend more time on these platforms than on any other site. Today, social networks are used by numerous NGOs to spread their ideas to a larger public and to combat apathy. They enable the beneficiaries, employees and partners of Terre des hommes ( Tdh ) to have a voice. Utilised in the right way, they will help promote the work done by Tdh by informing the public about the situation of children around the world and permitting the public to present new concerns. -

An Uneasy Life of a Flying Writer

Title An Uneasy Life of A Flying Writer Author(s) ATARASHI, Toshiharu Citation 北大法学研究科ジュニア・リサーチ・ジャーナル, 8, 329-350 Issue Date 2001-12 Doc URL http://hdl.handle.net/2115/22334 Type bulletin (article) File Information 8_P329-350.pdf Instructions for use Hokkaido University Collection of Scholarly and Academic Papers : HUSCAP An Uneasy Life of A Flying Writer ~m~1'F*O)gPJTO)t:tv)A5t Atarashi Toshiharu Table of Contents I. Introduction .......................................................................... 331 A. Aim of the thesis 331 B. Historical background 331 II. Saint-Exupery and Civil Aviation ........................................... .. 332 A. First flight as a boy .......................................................... .. 333 (1) Moved to Le Mans ........................................................ 333 (2) Baptized to aviation 334 B. Civil pilot license 334 (1) Troubled years 334 (2) Publication of his debut work 335 C. Airmail pilot ....................................................................... 335 (1) Entering Latecoere Company 335 (2) Airfield chief in the desert 336 (3) Return to France 337 (4) To South America 337 (5) Encounter with "Tropical Sheherazade" 338 (6) An internal trouble within the company 338 (7) Night Flight .................................................................... 338 D. Flying journalist/adventurer ............................................... 339 (1) Wasteful life and abortive adventure flight ....................... 339 (2) Another accident in Central America 339 (3) Visit to -

Terre Des Hommes International Federation International Secretariat Accountability Report Period Covered: 2014

Terre des Hommes International Federation International Secretariat Accountability Report Period covered: 2014 ©Photo Douglas Mansur-IPA Page 1 sur 23 Profile Disclosures 1. Strategy and Analysis 1.1 Statement of TDHIF-IS Secretary General, about the relevance and accountability of the organisation and its strategy 2014 has been a year of significant progress for Terre des Hommes International Federation (TDHIF): in all, we ran 870 development or humanitarian projects with 1’120 partner organisations with a total of 4’822’000 direct beneficiaries in 68 countries. We have measurable attributions and contributions to our different advocacy work at local, regional and global level. This reflects a significant increase in the reach of our work. We value greatly the International NGO Accountability Charter as a mechanism for reviewing and evaluating our work and increasing our transparency and accountability. This is our first year for which we are reporting to the Accountability Charter. The reporting is focused on the International Secretariat of the Terre des Hommes International Federation as a first step to get all the Member Organisations of the Federation report in a consolidated manner under the Accountability Charter. This report however consolidates our core commitments to accountability in terms of transparency, good governance, environmental responsibility, participation, people management, child safeguarding inclusion and diversity, and ethical fundraising. It forms part of our decisive plan to promote a culture of accountability and learning throughout the organization, so that we can ultimately increase and improve our impact. A number of measurable results on synergies and common advocacy with an acceleration in 2014 and 2015 include: Regional and country initiatives for meaningful synergies have developed in different complementary ways. -

Keeping Promises to Children Annual Report 2010

tellinaDesign s 50th A n n i v e r s A r y Keeping Promises to Children Annual report 2010 www.terredeshommes.org Terre des Hommes is dedicated to the promotion and implementation of children’s rights around the world in: running 1’196 development and humanitarian aid projects in 72 countries delivering protection, care and development opportunities to children lobbying governments to make necessary changes in legislation and practice raising general awareness about violations of children’s rights providing quality work and being accountable to its beneficiaries and stakeholders Keeping Promises to Children Coherent Action 2 Raffaele K. Salinari, President Preparing for the Future 3 Eylah Kadjar-Hamouda, Head of International Secretariat About Terre Des Hommes Who are We? 4 How we Operate 5 Where We Work 8 Activities And Results by Axes of Intervention Protecting Children from Exploitation and 10 Violence Health and Education: Providing the Essentials 16 Encouraging Child Development 19 Children in Emergencies: Bridging Relief to Development 21 Regional Highlights In Africa 23 In Asia In Europe In Latin America In the Middle East Communication A tool for human rights 25 Terre des Hommes in Figures 26 Auditor’s Report and Financial Statement 27 International Board and International Secretariat 30 Terre Des Hommes International Federation Members 31 Terre des Hommes International Federation International Secretariat Headquarters European Office 31 chemin Frank-Thomas 26 rue d’Edimbourg CH–1223 COLOGNY/GENEVA B–1050 BRUSSELS SWITZERLAND BELGIUM Tel: (41) 22 736 33 72 Tel: (32) 2 893 09 51 Fax: (41) 22 736 15 10 Fax: (32) 2 893 09 54 [email protected] [email protected] www.terredeshommes.org Terre des Hommes International Federation – Annual Report 2010 1 Keeping Promises to Children Coherent Action Photo:Diliberto© The year 2010 marks an important birthday for Terre des We know that the international financial crisis is still casting Hommes International Federation: we are 50 years old. -

Global Threat Assessment 2019 Working Together to End the Sexual Exploitation of Children Online

Global Threat Assessment 2019 Working together to end the sexual exploitation of children online WARNING: This document contains case studies some readers may find distressing. It is not suitable for young children. Reader discretion is advised. Acknowledgements The WePROTECT Global Alliance wish to thank the following organisations for providing specialist advice, and PA Consulting Group for researching and compiling this report: Aarambh Foundation (India) ECPAT International eSafety Commissioner (Australia) European Commission Europol International Justice Mission Internet Watch Foundation INTERPOL National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (US) National Crime Agency (UK) The Global Partnership to End Violence Against Children The Lucy Faithfull Foundation UNICEF Ghana US Department of Justice © Crown Copyright 2019 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/ version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected]. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. WeProtect Global Alliance – Global Threat Assessment 2019 1 Contents 01 Foreword 2 02 Aims of the Global Threat Assessment 5 03 Summary conclusions 7 04 Technology trends 10 05 Changing offender behaviours 18 06 Victims’ online exposure 26 07 The socio-environmental context 34 08 The sphere of harm 40 09 Forward look 44 10 Endnotes 46 2 WeProtect Global Alliance – Global Threat Assessment 2019 01 Foreword by Ernie Allen, Chair of WePROTECT Global Alliance At our last Summit, increasingly unable to identify and flag co-hosted with the malicious use of their own platforms. -

The Little Prince Director's Notes for School's Educational Package Antoine De Saint Exupéry and the Mysteries of Life How Is I

The Little Prince Director's Notes for School's educational package Antoine de Saint Exupéry and the Mysteries of Life How is it possible for a powerful creature like an elephant to be consumed by a boa constrictor? Antoine St. Exupery answers: the same way as its possible for a powerful adult to be consumed by the necessities, duties and power-plays of everyday life. How easily we confuse the priorities of life and lose our sense of wonder! In terms of keeping the imaginative spirit alive, life is a dangerous business; whether you live on the little prince's imaginary planet where he must clean out three volcanoes daily and uproot life sucking baobab trees, or whether, like the pilot, you fly over the deserts of the world. As the flower says, "the danger is so little understood" that people are often consumed without even knowing it. The Pilot tells us early in the play that understanding the dangers of life's boa constrictors, as a child does vividly, can make a person lonely and misunderstood. We all feel this way at times, and the power of the story is that it can help guide us out of the lonely desert. THE LITTLE PRINCE gives us the story of two very lonely people, a pilot and a fantastical little prince. They have lost the balance between their inner imaginations and the external demands of life , and they have both sought to explore their feelings by flying to other lands. The realities of balance and flight can both be shown by a teeter-totter, and we felt it was so important for audiences to feel them in action that we used one for the set. -

Justice and Home Affairs

For children, their rights, and equitable development Statement How Trafficked Children are exploited in Europe EU Forum on the prevention of organised crime Roundtable: “EU action against child trafficking and related forms of exploitation” organised by the European Commission Directorate-General Justice and Home Affairs Brussels 26th of May 2004, Borschette Centre Dr. Boris Scharlowski Mr. Salvatore Parata Co-ordination International Campaign against Child Trafficking International Federation Terre des Hommes Mister Chair, dear representatives of European States and European Institutions, dear representatives from international organisations, dear colleagues from non-governmental organisations, I would like to start by thanking the European Commission, DG Justice and Home Affairs for inviting the International Federation Terre des Hommes and its International Campaign against Child Trafficking to take part in this Forum. The fact that my organisation has been invited to take the floor in this forum to discuss the problem of child trafficking in Europe and to present our recommendations in favour of the victims, gives a clear positive signal. Through your invitation to this discussion among experts, you are making an important contribution to putting a stop to the trafficking in human beings. You are also contributing to giving the victims hope of a better future. As Co-ordinator of the International Campaign against Child Trafficking I intend to explain how trafficked children are exploited in Europe. Following this I would like to go on to give you some impressions of Terre des Hommes projects in Albania and Greece. Finally I will describe our main recommendations to the European Commission and European Parliament.