Introduction 1. the Patterns of Abuse Which Terre Des Hommes Is Tackling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Palace Sculptures of Abomey

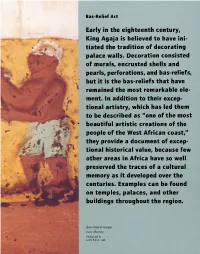

Bas-Relief Art Early in the eighteenth century, King Agaja is believed to have ini tiated the tradition of decorating palace walls. Decoration consisted of murals, encrusted shells and pearls, perfo rations, and bas-reliefs, , but it is the bas-reliefs that have remained the most remarkable ele ment. In addition to their excep tional artistry, which has led them to be described as "one of the most " beautiful artistic creations of the people of the West African coast, rr they provide a document of excep tional historical value, because few other areas in Africa have so well preserved the traces of a cultural · . memory as it developed over the centuries. Exa mples can be found on temples, palaces, and other buildings throughout the region. Bas-relief at temple near Abomey. Photograph by Leslie Railler, 1996. BAS-RELIEF ART 49 Commonly called noudide in Fon, from the root word meaning "to design" or "to portray," the bas-reliefs are three-dimensional, modeled- and painted earth pictograms. Early examples of the form, first in religious temples and then in the palaces, were more abstract than figurative. Gradually, figurative depictions became the prevalent style, illustrating the tales told by the kings' heralds and other Fon storytellers. Palace bas-reliefs were fashioned according to a long-standing tradition of The original earth architectural and sculptural renovation. used to make bas Ruling monarchs commissioned new palaces reliefs came from ter and artworks, as well as alterations of ear mite mounds such as lier ones, thereby glorifying the past while this one near Abomey. bringing its art and architecture up to date. -

S a Rd in Ia

M. Mandarino/Istituto Euromediterraneo, Tempio Pausania (Sardinia) Land07-1Book 1.indb 97 12-07-2007 16:30:59 Demarcation conflicts within and between communities in Benin: identity withdrawals and contested co-existence African urban development policy in the 1990s focused on raising municipal income from land. Population growth and a neoliberal environment weakened the control of clans and lineages over urban land ownership to the advantage of individuals, but without eradicating the importance of personal relationships in land transactions or of clans and lineages in the political structuring of urban space. The result, especially in rural peripheries, has been an increase in land aspirations and disputes and in their social costs, even in districts with the same territorial control and/or the same lines of nobility. Some authors view this simply as land “problems” and not as conflicts pitting locals against outsiders and degenerating into outright clashes. However, decentralization gives new dimensions to such problems and is the backdrop for clashes between differing perceptions of territorial control. This article looks at the ethnographic features of some of these clashes in the Dahoman historic region of lower Benin, where boundaries are disputed in a context of poorly managed urban development. Such disputes stem from land registries of the previous but surviving royal administration, against which the fragile institutions of the modern state seem to be poorly equipped. More than a simple problem of land tenure, these disputes express an internal rejection of the legitimacy of the state to engage in spatial structuring based on an ideal of co-existence; a contestation that is put forward with the de facto complicity of those acting on behalf of the state. -

Rapport De L'etude Du Concept Sommaire Pour Le Projet De Construction De Salles De Classe Dans Les Ecoles Primaires (Phase 4)

Ministère de l’Enseignement No. Primaire, de l’Alphabétisation et des Langues Nationales République du Bénin RAPPORT DE L’ETUDE DU CONCEPT SOMMAIRE POUR LE PROJET DE CONSTRUCTION DE SALLES DE CLASSE DANS LES ECOLES PRIMAIRES (PHASE 4) EN REPUBLIQUE DU BENIN Septembre 2007 Agence Japonaise de Coopération Internationale DAIKEN SEKKEI, INC. GM JR 07-155 Ministère de l’Enseignement Primaire, de l’Alphabétisation et des Langues Nationales République du Bénin RAPPORT DE L’ETUDE DU CONCEPT SOMMAIRE POUR LE PROJET DE CONSTRUCTION DE SALLES DE CLASSE DANS LES ECOLES PRIMAIRES (PHASE 4) EN REPUBLIQUE DU BENIN Septembre 2007 Agence Japonaise de Coopération Internationale DAIKEN SEKKEI, INC. AVANT-PROPOS En réponse à la requête du Gouvernement de la République du Bénin, le Gouvernement du Japon a décidé d'exécuter par l'entremise de l'agence japonaise de coopération internationale (JICA) une étude du concept sommaire pour le projet de construction de salles de classes dans les écoles primaires (Phase 4). Du 17 février au 18 mars 2007, JICA a envoyé au Bénin, une mission. Après un échange de vues avec les autorités concernées du Gouvernement, la mission a effectué des études sur les sites du projet. Au retour de la mission au Japon, l'étude a été approfondie et un concept sommaire a été préparé. Afin de discuter du contenu du concept sommaire, une autre mission a été envoyée au Bénin du 18 au 31 août 2007. Par la suite, le rapport ci-joint a été complété. Je suis heureux de remettre ce rapport et je souhaite qu'il contribue à la promotion du projet et au renforcement des relations amicales entre nos deux pays. -

Caractéristiques Générales De La Population

République du Bénin ~~~~~ Ministère Chargé du Plan, de La Prospective et du développement ~~~~~~ Institut National de la Statistique et de l’Analyse Economique Résultats définitifs Caractéristiques Générales de la Population DDC COOPERATION SUISSE AU BENIN Direction des Etudes démographiques Cotonou, Octobre 2003 1 LISTE DES TABLEAUX Tableau 1: Population recensée au Bénin selon le sexe, les départements, les communes et les arrondissements............................................................................................................ 3 Tableau G02A&B : Population Résidente recensée dans la commune de KANDI selon le sexe et par année d’âge ......................................................................... 25 Tableau G02A&B : Population Résidente recensée dans la commune de NATITINGOU selon le sexe et par année d’âge......................................................................................... 28 Tableau G02A&B : Population Résidente recensée dans la commune de OUIDAH selon le sexe et par année d’âge............................................................................................................ 31 Tableau G02A&B :Population Résidente recensée dans la commune de PARAKOU selon le sexe et par année d’âge (Commune à statut particulier).................................................... 35 Tableau G02A&B : Population Résidente recensée dans la commune de DJOUGOU selon le sexe et par année d’âge .................................................................................................... 40 Tableau -

FORS-LEPI Rapport Observation Recensement, Mai 2010

www.fors-lepi.org RAPPORT DE SYNTHESE DES MISSIONS D’OBSERVATION DE LA PHASE DU RECENSEMENT PORTE A PORTE Périodes d’observation : 30 Avril au 4 mai 2010 & 16 au 17 mai 2010 Mai 2010 SOMMAIRE Pages REMERCIEMENTS 4 INTRODUCTION 5 BREVE NOTE METHODOLOGIQUE 6 I- OBSERVATIONS D’ORDRE GENERAL 7 II- DYSFONCTIONNEMENTS OBSERVES 13 III- IRREGULARITES CONSTATEES 18 IV- CONCLUSION/RECOMMANDATIONS 23 2 SIGLES ET ABREVIATIONS CCS : Commission Communale de Supervision CPS : Commission Politique de Supervision DRA : Délégué au Recensement de l’Arrondissement F « oui » : fréquence de oui en réponse aux questionnaires administrés F « non » : fréquence de non en réponse aux questionnaires administrés FORS-LEPI : Front des Organisations de la Société civile pour la réalisation de la LEPI INSAE : Institut National de Statistiques et d’Analyse Economique LEPI : Liste Electorale Permanente Informatisée MCRE : Mission Communale de Recensement Electoral MIRENA : Mission Indépendante de Recensement Electoral National Approfondi PAREL : Projet d’Appui à la Réalisation de la LEPI VNU : Volontaire des Nations Unies ZDE : Zone de Dénombrement Electorale 3 REMERCIEMENTS Que les autorités politiques locales (maires, chefs d’arrondissements, chefs quartiers et chefs villages), les autorités administratives (gendarmeries, polices et autres) et les acteurs techniques (MCRE, DRA, VNU…) reçoivent les sincères remerciements des ONGs réunies au sein de FORS-LEPI pour l’assistance et les renseignements fournis aux observateurs. Une fois encore, le Front des Organisations de la Société Civile pour la réalisation de la LEPI (FORS-LEPI) saisit l’occasion de ce rapport pour témoigner sa gratitude à l’ensemble des partenaires techniques et financiers qui le soutiennent dans son action de veille pour la réalisation de la LEPI au Bénin. -

'Because We Struggle to Survive'

“Because we struggle to survive” Child Labour among Refugees of the Syrian Conflict Child Labour Report 2016 Disclaimer terre des hommes Siège | Hauptsitz | Sede | Headquarters Avenue de Montchoisi 15, CH-1006 Lausanne T +41 58 611 06 66, F +41 58 611 06 77 E-mail : [email protected], CCP : 10-11504-8 Research support: Ornella Barros, Dr. Beate Scherrer, Angela Großmann Authors: Barbara Küppers, Antje Ruhmann Photos : Front cover, S. 13, 37: Servet Dilber S. 3, 8, 12, 21, 22, 24, 27, 47: Ollivier Girard S. 3: Terre des Hommes International Federation S. 3: Christel Kovermann S. 5, 15: Terre des Hommes Netherlands S. 7: Helmut Steinkeller S. 10, 30, 38, 40: Kerem Yucel S. 33: Terre des hommes Italy The study at hand is part of a series published by terre des hommes Germany annually on 12 June, the World Day against Child Labour. We would like to thank terre des hommes Germany for their excellent work, as well as Terre des hommes Italy and Terre des Hommes Netherlands for their contributions to the study. We would also like to thank our employees, especially in the Middle East and in Europe for their contributions to the study itself, as well as to the work of editing and translating it. Terre des hommes (Lausanne) is a member of the Terre des Hommes International Federation (TDHIF) that brings together partner organisations in Switzerland and in other countries. TDHIF repesents its members at an international and European level. First published by terre des hommes Germany in English and German, June 2016. -

LOYALTY in the WORKS of SAINT-EXUPBRY a Thesis

LOYALTY IN THE WORKS OF SAINT-EXUPBRY ,,"!"' A Thesis Presented to The Department of Foreign Languages The Kansas State Teachers College of Emporia In Partial Fulfillment or the Requirements for the Degree Mastar of Science by "., ......, ~:'4.J..ry ~pp ~·.ay 1967 T 1, f" . '1~ '/ Approved for the Major Department -c Approved for the Graduate Council ~cJ,~/ 255060 \0 ACKNOWLEDGMENT The writer wishes to extend her sincere appreciation to Dr. Minnie M. Miller, head of the foreign language department at the Kansas State Teachers College of Emporia, for her valuable assistance during the writing of this thesis. Special thanks also go to Dr. David E. Travis, of the foreign language department, who read the thesis and offered suggestions. M. E. "Q--=.'Hi" '''"'R ? ..... .-.l.... ....... v~ One of Antoine de Saint-Exupe~J's outstanding qualities was loyalty. Born of a deep sense of responsi bility for his fellowmen and a need for spiritual fellow ship with them it became a motivating force in his life. Most of the acts he is remeffibered for are acts of fidelityo Fis writings too radiate this quality. In deep devotion fo~ a cause or a friend his heroes are spurred on to unusual acts of valor and sacrifice. Saint-Exupery's works also reveal the deep movements of a fervent soul. He believed that to develop spiritually man mQst take a stand and act upon his convictions in the f~c0 of adversity. In his boo~ UnSens ~ la Vie, l he wrote: ~e comprenez-vous Das a~e le don de sol, le risque, ... -

Monographie Des Communes Des Départements De L'atlantique Et Du Li

Spatialisation des cibles prioritaires des ODD au Bénin : Monographie des communes des départements de l’Atlantique et du Littoral Note synthèse sur l’actualisation du diagnostic et la priorisation des cibles des communes Monographie départementale _ Mission de spatialisation des cibles prioritaires des ODD au Bénin _ 2019 1 Une initiative de : Direction Générale de la Coordination et du Suivi des Objectifs de Développement Durable (DGCS-ODD) Avec l’appui financier de : Programme d’appui à la Décentralisation et Projet d’Appui aux Stratégies de Développement au Développement Communal (PDDC / GIZ) (PASD / PNUD) Fonds des Nations unies pour l'enfance Fonds des Nations unies pour la population (UNICEF) (UNFPA) Et l’appui technique du Cabinet Cosinus Conseils Monographie départementale _ Mission de spatialisation des cibles prioritaires des ODD au Bénin _ 2019 2 Tables des matières LISTE DES CARTES ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 SIGLES ET ABREVIATIONS ......................................................................................................................................... 5 1.1. BREF APERÇU SUR LES DEPARTEMENTS DE L’ATLANTIQUE ET DU LITTORAL ................................................ 7 1.1.1. INFORMATIONS SUR LE DEPARTEMENT DE L’ATLANTIQUE ........................................................................................ 7 1.1.1.1. Présentation du Département de l’Atlantique ...................................................................................... -

Water Supply and Waterbornes Diseases in the Population of Za- Kpota Commune (Benin, West Africa)

International Journal of Engineering Science Invention (IJESI) ISSN (Online): 2319 – 6734, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 6726 www.ijesi.org ||Volume 7 Issue 6 Ver II || June 2018 || PP 33-39 Water Supply and Waterbornes Diseases in the Population of Za- Kpota Commune (Benin, West Africa) Léocadie Odoulami, Brice S. Dansou & Nadège Kpoha Laboratoire Pierre PAGNEY, Climat, Eau, Ecosystème et Développement LACEEDE)/DGAT/FLASH/ Université d’Abomey-Calavi (UAC). 03BP: 1122 Cotonou, République du Bénin (Afrique de l’Ouest) Corresponding Auther: Léocadie Odoulami Summary :The population of the common Za-kpota is subjected to several difficulties bound at the access to the drinking water. This survey aims to identify and to analyze the problems of provision in drinking water and the risks on the human health in the township of Za-kpota. The data on the sources of provision in drinking water in the locality, the hydraulic infrastructures and the state of health of the populations of 2000 to 2012 have been collected then completed by information gotten by selected 198 households while taking into account the provision difficulties in water of consumption in the households. The analysis of the results gotten watch that 43 % of the investigation households consume the water of well, 47 % the water of cistern, 6 % the water of boring, 3% the water of the Soneb and 1% the water of marsh. However, the physic-chemical and bacteriological analyses of 11 samples of water of well and boring revealed that the physic-chemical and bacteriological parameters are superior to the norms admitted by Benin. The consumption of these waters exposes the health of the populations to the water illnesses as the gastroenteritis, the diarrheas, the affections dermatologic,.. -

Monographie Des Départements Du Zou Et Des Collines

Spatialisation des cibles prioritaires des ODD au Bénin : Monographie des départements du Zou et des Collines Note synthèse sur l’actualisation du diagnostic et la priorisation des cibles des communes du département de Zou Collines Une initiative de : Direction Générale de la Coordination et du Suivi des Objectifs de Développement Durable (DGCS-ODD) Avec l’appui financier de : Programme d’appui à la Décentralisation et Projet d’Appui aux Stratégies de Développement au Développement Communal (PDDC / GIZ) (PASD / PNUD) Fonds des Nations unies pour l'enfance Fonds des Nations unies pour la population (UNICEF) (UNFPA) Et l’appui technique du Cabinet Cosinus Conseils Tables des matières 1.1. BREF APERÇU SUR LE DEPARTEMENT ....................................................................................................... 6 1.1.1. INFORMATIONS SUR LES DEPARTEMENTS ZOU-COLLINES ...................................................................................... 6 1.1.1.1. Aperçu du département du Zou .......................................................................................................... 6 3.1.1. GRAPHIQUE 1: CARTE DU DEPARTEMENT DU ZOU ............................................................................................... 7 1.1.1.2. Aperçu du département des Collines .................................................................................................. 8 3.1.2. GRAPHIQUE 2: CARTE DU DEPARTEMENT DES COLLINES .................................................................................... 10 1.1.2. -

Notions of Self and Nation in French Author

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 6-27-2016 Notions of Self and Nation in French Author- Aviators of World War II: From Myth to Ambivalence Christopher Kean University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Kean, Christopher, "Notions of Self and Nation in French Author-Aviators of World War II: From Myth to Ambivalence" (2016). Doctoral Dissertations. 1161. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1161 Notions of Self and Nation in French Author-Aviators of World War II: From Myth to Ambivalence Christopher Steven Kean, PhD University of Connecticut, 2016 The traditional image of wartime aviators in French culture is an idealized, mythical notion that is inextricably linked with an equally idealized and mythical notion of nationhood. The literary works of three French author-aviators from World War II – Antoine de Saint- Exupéry, Jules Roy, and Romain Gary – reveal an image of the aviator and the writer that operates in a zone between reality and imagination. The purpose of this study is to delineate the elements that make up what I propose is a more complex and even ambivalent image of both individual and nation. Through these three works – Pilote de guerre (Flight to Arras), La Vallée heureuse (The Happy Valley), and La Promesse de l’aube (Promise at Dawn) – this dissertation proposes to uncover not only the figures of individual narratives, but also the figures of “a certain idea of France” during a critical period of that country’s history. -

Rapport Définitif De La Sélection Des 70 Formations Sanitaires (FS) Témoins Pour Les FS Du Projet FBR Du Bénin Par Joseph FLENON, Consultant

Rapport définitif de la sélection des 70 formations sanitaires (FS) témoins pour les FS du Projet FBR du Bénin par Joseph FLENON, Consultant. Dans la première partie du point n°1 de ce contrat en cours d’exécution, j’ai sélectionné de manière aléatoire simple 8 Zones Sanitaires (ZS) témoins (au lieu de 5 ou 6) pour les 8 ZS du projet FBR du Bénin et j’en ai fait un rapport Dans cette deuxième partie du point n°1, j’ai procédé à la sélection de 70 formations sanitaire (FS) dans 10 ZS témoins (au lieu de 8ZS témoins) car suivant les critères de sélection de ces FS, les 8ZS sélectionnées dans la première partie du point n°1, m’ont permis de sélectionner à leur tour 47 FS témoins au lieu de 70 FS témoins. La Sélection aléatoire simple d’une ZS contrôle dans chacun des 8 listes a donné les 8 ZS contrôles suivantes : 1.ZS Bohicon-Zakpota-Zogbodomey : ZS contrôle : ZS Djidja-Abomey-Agbangnizoun 2.ZS Covè-Ouinhi-Zangnanado : ZS contrôle : ZS Pobè-Ketou-Adja-Ouèrè 3.ZS Lokossa-Athiémé : ZS contrôle : ZS Aplahoué-Djakotomè-Dogbo 4.ZS Ouidah-Kpomassè-Tori-Bossito : ZS contrôle : ZS Allada-Toffo-Zê 5.ZS Porto-Novo-Aguégués-Sèmè-Podji : ZS contrôle : ZS Cotonou 6 6.ZS Adjohoun-Bonou-Dangbo : ZS contrôle : ZS Abomey-Calavi-Sô-Ava 7.ZS Banikoara : ZS contrôle : ZS Kandi-Gogounou-Ségbana 8.ZS Kouandé-Ouassa-Péhunco-Kérou : ZS contrôle : ZS Tanguiéta-Cobly-Matéri Les critères de sélections des FS témoins proposés dans les TDR peuvent être classés en critères exclusifs (être à moins de 15 km de la frontière d’une ZS du Projet FBR et avoir moins de 2 personnels qualifiés) et en critères non exclusifs (certaines FS témoins doivent avoir au moins 15 CPN par jour).