Carman Pozzobon Is Running for Captain Nichola Kathleen Sarah Goddard in 2006, Capt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Executive Brief

EXECUTIVE BRIEF CHIEF DEVELOPMENT OFFICER TABLE OF CONTENTS The Opportunity………………………………………………………………………….. 3 About True Patriot Love…………………………………………………………….…....3 Impact……………………………………………………………………………….……..5 Additional Background & Resources……………….………………………….…….....7 The Ideal Candidate……………………………………………………………………...8 Key Areas of Responsibilities…………………………………………………………...8 Qualifications and Competencies…………………..…………………………………..9 Biography: Nick Booth, MVO CEO, True Patriot Love Foundation ………………..10 Biography: Shaun Francis, Founder & Chair, True Patriot Love Foundation……..11 Organizational Chart……………………………………………………………………12 FOR MORE INFORMATION KCI (Ketchum Canada Inc.) has been retained to conduct this search on behalf of True Patriot Love Foundation. For more information about this leadership opportunity, please contact Ellie Rusonik, Senior Search Consultant at [email protected]. All inquiries and applications will be held in strict confidence. To apply, please send a resume and letter of interest to the email address above by August 5, 2019 True Patriot Love welcomes and encourages applications from all qualified applicants. Accommodations are available on request for candidates taking part in all aspects of the selection process. Chief Development Officer THE OPPORTUNITY True Patriot Love Foundation is Canada’s leading charity supporting those who serve in the Canadian Armed Forces, Veterans and their families. Established in 2009 during the war in Afghanistan, it has since distributed over $25 million to fund more than 750 programs that support mental health, physical rehabilitation, transition to life after service and the unique needs of children and families. The foundation also actively helps to ensure the needs of those who serve remain in the minds of the public through high profile expeditions and events. This includes helping to secure the bid for the 2017 Invictus Games in Toronto. -

Birchall Leadership Award 2020

BIRCHALL LEADERSHIP AWARD 2020 The Royal Military Colleges Foundation in partnership with True Patriot Love Foundation’s Captain Nichola Goddard Fund Calgary, Alberta March 9, 2020 MEDIA ADVISORY Prestigious Leadership Award to be Presented to Olympian Beckie Scott in Calgary Calgary, AB – Beckie Scott, an internationally-recognized leader in sport and an Olympic gold medalist in cross country skiing, one of Canada’s modern heroes, will be honoured in Calgary on March 9, 2020 with the prestigious Birchall Leadership Award, created in honour of a Canadian World War II hero, 2364 Air Commodore Leonard Birchall. The Award will be presented at True Patriot Love Foundation's Captain Nichola Goddard Roundtable and Reception hosted by Bennett Jones LLP. Ms. Scott has served as an athletes’ representative at the highest level of international sport and is recognized globally for her efforts on behalf of clean, fair doping-free sport and athletes’ rights. Beckie Scott exemplifies Air Commodore Birchall’s qualities including the ability to lead in the face of difficulty or adversity to promote the welfare and safety of others. The Birchall Leadership Award is presented biennially by the Royal Military Colleges Foundation to a deserving Canadian to honour the memory of 2364 Air Commodore Leonard Birchall (1915-2004), who was an exemplary leader during World War II in combat and in prisoner of war camps, and post-war as a senior RCAF commander. Air Commodore Birchall, while pilot of an RCAF Canso seaplane on April 4th, 1942, spotted a Japanese raiding fleet off the coast of Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). His report allowed a Royal Navy fleet to save most of their ships and reduce damage to bases on the island. -

2018 Annual Report True Patriot Love Foundation Strengthening Military and Veteran Families

2018 ANNUAL REPORT TRUE PATRIOT LOVE FOUNDATION STRENGTHENING MILITARY AND VETERAN FAMILIES. TABLE OF CONTENTS 4 Letter to Supporters 6 About True Patriot Love Foundation 7 Our Impact 22 Financial Statements 23 Funding Recipients 25 2018 Donors 26 Process, Governance & Structure TRUE PATRIOT LOVE 2018 ANNUAL REPORT 3 Letter to Supporters Dear Friends of True Patriot Love, Late in 2018, we said goodbye to CEO Bronwen Evans who, along with her team, We are very pleased to present True Patriot Love built True Patriot Love from the ground Foundation’s 2018 Annual Report, which reflects a milestone up and into the largest organization of year for the foundation in many ways. its kind in Canada. We thank Bronwen for all her hard work and dedication to our cause. As she stepped down, we In 2018, we continued to focus on driving national impact for military were pleased to welcome Nick Booth, a members, Veterans and their families, committing more than $3.2 million to seasoned leader in the charitable sector, help fund 75 programs and services across Canada. This report recognizes the who has robust international experience, impactful, innovative work being done by many of our program partners. The which includes being the founding CEO True Patriot Love team knows that our work would not be possible without the of The Royal Foundation and an initiator generous backing of our donors and supporters, so thank you, most sincerely, of the Invictus Games. As we enter our for helping us change lives. second decade, Nick and the team are In November, we celebrated our tenth Tribute Gala – the largest event of its well poised to take True Patriot Love to kind that honours the brave men and women who have served our nation. -

Captain Nichola Goddard Leadership Series Presented by Bennett Jones

CAPTAIN NICHOLA GODDARD LEADERSHIP SERIES PRESENTED BY BENNETT JONES VANCOUVER - MARCH 10, 2020 5:00 p.m. - 7:30 p.m. SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITIES Charitable Registration Number: 81464 6493 RR0001 CAPTAIN NICHOLA GODDARD LEADERSHIP SERIES: SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITIES ABOUT THE EVENT Captain Nichola Goddard Leadership Series - Vancouver Tuesday, March 10, 2020 Bennett Jones 666 Burrard St #2500, Vancouver, BC V6C 2X8 The Vancouver edition of the Captain Nichola Goddard Leadership Series, presented by Bennett Jones, will feature a panel discussion with a group of remarkable women from the Canadian Armed Forces, focusing on the themes of resilience and agility in leadership. Bringing together military members, business leaders and community partners, the reception will provide insight and generate inspiring discussion surrounding the unique experiences women face in the Canadian Armed Forces. Speakers will share inspirational stories of courage, leadership and resiliency while speaking to how their military careers have shaped and defined them. Meet & greet Panel discusssion Networking with Q&A period 5:00 p.m. - 6:00 p.m. 6:00 p.m. - 7:00 p.m. 7:00 p.m. - 7:30 p.m. For more information, to purchase single tickets, or to make a donation please visit: www.truepatriotlove.com/goddard-reception-2020/ For questions and to secure your involvement, please contact: Meighan Bell Chief Development Officer [email protected] or call 647.608.6940 True Patriot Love Foundation True Patriot Love Foundation is a national charity that is changing the lives of military members, Veterans and their families across Canada. By funding more than 825 programs that support mental health, physical rehabilitation, transition to life after service, and the unique needs of children and families, we’ve helped 30,000 military and Veteran families in need over the past decade. -

The Veteran's Voice

The Veteran’s Voice Throughout her life, Joyce converted the old World Allen has held many titles: War Two Lancaster Bombers mother, grandmother, past into full-fledged spy planes. The member of the board of bomb-bay doors became “bulb-bay” governors at the University of doors, and were retrofitted with up to 25 cameras snapping Winnipeg, lifelong learner, a photographs at a time, in order to provide images of as large a citizen first of Britain and later territory as possible. The ultimate objective: to monitor the build- of Canada, and also a proud up of Russian military installations and to track Soviet activities Manitoban. But as MSBA on land and at sea. discovered during our latest “Veteran’s Voice” Interview, Beyond these few details concerning her service however, Joyce Joyce is also a veteran. remains tight-lipped. Some secrets are simply not meant to be shared, even to this day. If there was one revelation from our Joyce Allen As a young child growing up interview however, it was that for every “James Bond” employed during the final years of the by Great Britain during the Cold War, there was also a Joyce Allen! Second World War, she well recalls the need to seek refuge in air raid shelters as German rockets rained down on civilians, killing We would encourage all Manitobans to watch our video over 50,000 of her fellow Britons. This experience motivated interview with Joyce, to learn more about her thoughts on Joyce to serve her country, even with the war at a close. -

Lowered, Shipped, and Fastened: Private Grief and the Public Sphere in Canada's Afghanistan War

Lowered, Shipped, and Fastened: Private Grief and the Public Sphere in Canada's Afghanistan War by Michel Legault, B.A. (Hons.) A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2012 Michel Legault Library and Archives Bibliotheque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du 1+1 Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-93599-6 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-93599-6 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

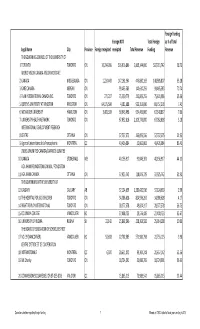

Canadian-Charities-Table-A.Pdf

Foreign Funding Foreign NOT Total Foreign as % of Total Legal Name City Province Foreign receipted receipted Total Revenue Funding Revenue THE GOVERNING COUNCIL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF 1 TORONTO TORONTO ON 10,294,936 526,916,806 2,865,144,000 537,211,742 18.75 WORLD VISION CANADA‐VISION MONDIALE 2 CANADA MISSISSAUGA ON 1,224,443 147,161,364 445,830,169 148,385,807 33.28 3 CARE CANADA NEPEAN ON 99,465,583 140,610,259 99,465,583 70.74 4 PLAN INTERNATIONAL CANADA INC. TORONTO ON 271,207 75,330,779 213,809,255 75,601,986 35.36 5 QUEEN'S UNIVERSITY AT KINGSTON KINGSTON ON 64,175,590 4,581,688 923,353,036 68,757,278 7.45 6 MCMASTER UNIVERSITY HAMILTON ON 3,405,339 63,943,498 954,409,000 67,348,837 7.06 7 UNIVERSITY HEALTH NETWORK TORONTO ON 67,052,818 2,105,776,000 67,052,818 3.18 INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT RESEARCH 8 CENTRE OTTAWA ON 57,737,575 263,099,556 57,737,575 21.95 9 Agence Universitaire de la Francophonie MONTREAL QC 43,426,084 52,062,002 43,426,084 83.41 DUCKS UNLIMITED CANADA/CANARDS ILLIMITES 10 CANADA STONEWALL MB 40,156,917 91,046,301 40,156,917 44.11 AGA KHAN FOUNDATION CANADA / FONDATION 11 AGA KHAN CANADA OTTAWA ON 37,925,742 118,879,729 37,925,742 31.90 THE GOVERNORS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF 12 CALGARY CALGARY AB 37,124,639 1,280,420,916 37,124,639 2.90 13 THE HOSPITAL FOR SICK CHILDREN TORONTO ON 34,386,628 824,936,261 34,386,628 4.17 14 RIGHT TO PLAY INTERNATIONAL TORONTO ON 28,277,578 49,824,317 28,277,578 56.75 15 COLUMBIA COLLEGE VANCOUVER BC 27,408,723 29,576,489 27,408,723 92.67 16 UNIVERSITY OF REGINA REGINA SK 22,142 25,892,096 258,363,582 25,914,238 10.03 THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF SCHOOL DISTRICT 17 NO. -

Locating Global Order

LOCATING GLOBAL ORDER charbonneau_cox hi_res.pdf 1 6/23/2010 2:55:02 PM charbonneau_cox hi_res.pdf 2 6/23/2010 2:55:08 PM LOCATING GLOBAL ORDER American Power and Canadian Security after 9/11 Edited by Bruno Charbonneau and Wayne S. Cox charbonneau_cox hi_res.pdf 3 6/23/2010 2:55:09 PM © UBC Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior written permission of the publisher, or, in Canada, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright (Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency), www.accesscopyright.ca. Printed in Canada on FSC-certified ancient-forest-free paper (% post-consumer recycled) that is processed chlorine- and acid-free. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Locating global order : American power and Canadian security after / / edited by Bruno Charbonneau and Wayne S. Cox. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN ---- . Canada – Foreign relations – st century. United States – Foreign relations – st century. National security – Canada. National security – United States. Afghan War, - – Participation, Canadian. Canada – Social conditions – st century. World politics – st century. September Terrorist Attacks, – Influence. I. Charbonneau, Bruno, - II. Cox, Wayne S., - FC.L . C-- UBC Press gratefully acknowledges the financial support for our publishing program of the Government of Canada (through the Canada Book Fund), the Canada Council for the Arts, and the British Columbia Arts Council. Printed and bound in Canada by Friesens Set in Futura Condensed and Warnock Pro by Artegraphica Design Co. Ltd. -

ON TRACK Vol 15 No 2.Indd

Independent and Informed ON TRACK Indépendant et Informé The Conference of Defence Associations Institute ● L’Institut de la Conférence des Associations de la Défense Summer / Été Volume 15, Number 2 2010 International Trade and National Security in Historical Perspective Canada’s Interests Celebrating Canada’s Naval Aviation Heritage Urban Bias in Counterinsurgency Operations Israel’s Maritime Blockade of Gaza DND Photo / Photo DDN CDA INSTITUTE BOARD OF DIRECTORS Admiral (Ret’d) John Anderson Général (Ret) Maurice Baril Dr. David Bercuson L’hon. Jean-Jacques Blais Dr. Douglas Bland Mr. Robert T. Booth Mr. Thomas Caldwell Mr. Mel Cappe Dr. Jim Carruthers Mr. Paul H. Chapin Mr. Terry Colfer Dr. John Scott Cowan Mr. Dan Donovan Lieutenant-général (Ret) Richard Evraire Honourary Lieutenant-Colonel Justin Fogarty Mr. Robert Fowler Colonel, The Hon. John Fraser Lieutenant-général (Ret) Michel Gauthier Rear-Admiral (Ret’d) Roger Girouard Dr. Bernd A. Goetze Honourary Colonel Blake C. Goldring Mr. Mike Greenley Général (Ret) Raymond Henault Honourary Colonel, Dr. Frederick Jackman The Hon. Colin Kenny Colonel (Ret’d) Brian MacDonald Major-General (Ret’d) Lewis MacKenzie Brigadier-General (Ret’d) W. Don Macnamara Lieutenant-général (Ret) Michel Maisonneuve General (Ret’d) Paul D. Manson Mr. John Noble The Hon. David Pratt Mr. Colin Robertson The Hon. Hugh Segal Colonel (Ret’d) Ben Shapiro Brigadier-General (Ret’d) Joe Sharpe M. André Sincennes Dr. Joel Sokolsky Rear-Admiral (Ret’d) Ken Summers Lieutenant-General (Ret’d) Jack Vance The Hon. Pamela Wallin ON TRACK VOLUME 15 NUMBER 2 CONTENTS CONTENU SUMMER / ÉTÉ 2010 PRESIDENT / PRÉSIDENT Dr. John Scott Cowan, BSc, MSc, PhD VICE PRESIDENT / VICE PRÉSIDENT Général (Ret’d) Raymond Henault, CMM, CD EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR / DIRECTEUR EXÉCUTIF From the Executive Director......................................................................4 Colonel (Ret) Alain M. -

Along the Highway: Landscapes of National Mourning in Canada

Along the Highway: Landscapes of National Mourning in Canada by Jordan Claire Hale A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Geography Department of Geography and Program in Planning University of Toronto © Copyright by Jordan Claire Hale 2014 ii Along the Highway: Landscapes of National Mourning in Canada Jordan Claire Hale Master of Arts in Geography Department of Geography and Program in Planning University of Toronto 2014 Abstract Between 2002 and 2011, 158 Canadian Forces soldiers died while serving in Afghanistan and were repatriated via Canadian Forces Base Trenton to the Office of the Chief Coroner of Ontario in Toronto for autopsy. The repatriation route took their bodies along Highway 401 in central Ontario, where thousands assembled on bridges above the highway to pay their respects. In this thesis, I detail the memorial landscape that developed around what came to be known as the Highway of Heroes, and I use this conception of the highway as a landscape to demonstrate the ways in which it participates in the ongoing remilitarization of Canada. Following the work of Judith Butler, I argue that the Highway of Heroes contributes to the production of a hierarchy of grievable subjects, and the act of memorializing soldiers is implicated in the erasure of other victims of state violence, including missing and murdered Indigenous women. iii Acknowledgments I am immensely grateful to have had the support of so many wonderful individuals throughout the research process. First and foremost, I thank my partner Greg J. Smith, whose patience, sense of humour, editing prowess, and driver’s license were invaluable to this project. -

The Unknown Soldier in the 21St Century: War Commemoration in Contemporary Canadian Cultural Production

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 7-17-2017 12:00 AM The Unknown Soldier in the 21st Century: War Commemoration in Contemporary Canadian Cultural Production Andrew Edward Lubowitz The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Manina Jones The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in English A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Andrew Edward Lubowitz 2017 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Lubowitz, Andrew Edward, "The Unknown Soldier in the 21st Century: War Commemoration in Contemporary Canadian Cultural Production" (2017). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 4875. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/4875 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract Over the past two decades, expressions of Canadian national identity in cultural production have become increasingly militarized. This is particularly noticeable since the late 1990s in the commemorative works that have been created, renovated, or re-inscribed in Canada or in important Canadian international sites such as the Vimy Memorial in France. An integral component to this militarization is the paradoxical figure of the Unknown Soldier, both a man and a symbol, known and unknown, individualized and universal. Despite its origins in Europe after the First World War, the Unknown Soldier Memorial tradition has been reinvigorated in a Canadian context in the twenty-first century resulting in an elevation of white masculine heroism while curtailing criticism of military praxis. -

Msms from Canada Gazette of 05 January 2019

M E R I T O R I O U S S E R V I C E M E D A L (M S M) C I V I L 05 January 2019 UPDATED: 10 March 2021 PAGES: 23 CURRENT TO: 05 January 2019 Canada Gazettes PREPARED BY: John Blatherwick, CM, CStJ, OBC, MD, FRCP(C), LLD(Hon) =================================================================================================== INDEX for MSMs from Canada Gazette of 05 January 2019 Page NAME TITLE FOR WHAT DECORATIONS / 03 BARBIER, Roland Ms Discreetly distributes winter clothing to Children MSM 04 BENNETT, Richard Mr Founded Relais trois montagnes Moncton MSM 05 BOESCH-LUCKING, Kathryn Lorna Ms Madagascar School Project (MSP) break poverty MSM 05 BOUCHARD, Caroline Mrs Created Fondation Jacques-Bouchard hospice MSM 05 BRAN LOPEZ, J. Gabriel Mr Founded Youth Fusion dropout rates across PQ MSM 06 BROSSEAU, Sylvain Ms Co-Founded Centre Philou, rehabilitation centre MSM 06 BROWN, Gregory Robert Medlock Mr Creator AsapSCIENCE YouTube Education Chann. MSM 06 CHÊNEVERT, Diane Ms Co-Founded Centre Philou, rehabilitation centre CQ MSM 07 CORNEILLE GRAVEL, Rachel Ms Director St. Anne’s Hospital – Modernize for Vets MSM 07 CRERAR, Norman D. Mr Founded Okanagan Military Tattoo MSM 04 DALLAIRE, John Raymond Mr Founded Relais trois montagnes Moncton MSM 07 DEL COL, Aldo E.J. Mr Founder Myeloma Canada MSM 08 DESJARDINS, Gilles Mr Benefactor of the National Capital Region MSM 08 EDMONDS, Virginia Ms Co-Founder Dr. Tom Pashby Sports Safety Fund MSM 09 FAIRBROTHER, John Morris Dr Vaccine against post-weaning diarrhea in piglets MSM 09 FARMER, Olivier Dr réaffiliation itinérance et santé mentale MSM 09 GAGNÉ, Lison Dr réaffiliation itinérance et santé mentale MSM 11 GALLERY, Brian O’Neill Mr Co-founded the Canadian Irish Studies Foundation MSM 10 GODDARD, Sally F.E.