Lowered, Shipped, and Fastened: Private Grief and the Public Sphere in Canada's Afghanistan War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JOHN NATER, MP John Nater, MP PERTH—WELLINGTON [email protected]

PHOTO 2020 JOHN NATER, MP John Nater, MP PERTH—WELLINGTON [email protected] THE PEACE TOWER 2020 January The Peace Tower is one of the most recognized landmarks in Canada. It is a splendid architectural piece with exquisite exterior and interior features. The name symbolizes the principles for which Canada fought in the Great War, as well as the high aspirations of the Canadian people. National and provincial symbols and emblems, combined with the country’s natural heritage, were selected for the main entrances of Canada’s most important public building. John Nater, MP [email protected] THE HOUSE OF COMMONS CHAMBER 2020 February The House of Commons Chamber is the most spacious room of the 1 Centre Block. The architects made provisions for 320 members, and the galleries were designed to 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 accommodate 580 people. The Chamber’s grand design and high level of decoration are in keeping 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 with the prestige of a plenary meeting room for Canada’s most important democratic institution. 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 John Nater, MP [email protected] THE SPEAKER’S CHAIR March The Speaker’s Chair is an exact 2020 replica of the original Speaker’s Chair designed for the British House of Commons around 1849. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 The Members of the United Kingdom Branch of the Empire Parliamentary Association presented the Chair to the 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Canadian House of Commons on May 20, 1921. -

Executive Brief

EXECUTIVE BRIEF CHIEF DEVELOPMENT OFFICER TABLE OF CONTENTS The Opportunity………………………………………………………………………….. 3 About True Patriot Love…………………………………………………………….…....3 Impact……………………………………………………………………………….……..5 Additional Background & Resources……………….………………………….…….....7 The Ideal Candidate……………………………………………………………………...8 Key Areas of Responsibilities…………………………………………………………...8 Qualifications and Competencies…………………..…………………………………..9 Biography: Nick Booth, MVO CEO, True Patriot Love Foundation ………………..10 Biography: Shaun Francis, Founder & Chair, True Patriot Love Foundation……..11 Organizational Chart……………………………………………………………………12 FOR MORE INFORMATION KCI (Ketchum Canada Inc.) has been retained to conduct this search on behalf of True Patriot Love Foundation. For more information about this leadership opportunity, please contact Ellie Rusonik, Senior Search Consultant at [email protected]. All inquiries and applications will be held in strict confidence. To apply, please send a resume and letter of interest to the email address above by August 5, 2019 True Patriot Love welcomes and encourages applications from all qualified applicants. Accommodations are available on request for candidates taking part in all aspects of the selection process. Chief Development Officer THE OPPORTUNITY True Patriot Love Foundation is Canada’s leading charity supporting those who serve in the Canadian Armed Forces, Veterans and their families. Established in 2009 during the war in Afghanistan, it has since distributed over $25 million to fund more than 750 programs that support mental health, physical rehabilitation, transition to life after service and the unique needs of children and families. The foundation also actively helps to ensure the needs of those who serve remain in the minds of the public through high profile expeditions and events. This includes helping to secure the bid for the 2017 Invictus Games in Toronto. -

'Turncoats, Opportunists, and Political Whores': Floor Crossers in Ontario

“‘Turncoats, Opportunists, and Political Whores’: Floor Crossers in Ontario Political History” By Patrick DeRochie 2011-12 Intern Ontario Legislature Internship Programme (OLIP) 1303A Whitney Block Queen’s Park Toronto, Ontario M7A 1A2 Phone: 416-325-0040 [email protected] www.olipinterns.ca www.facebook.com/olipinterns www.twitter.com/olipinterns Paper presented at the 2012 Annual meeting of the Canadian Political Science Association Edmonton, Alberta Friday, June 15th, 2012. Draft: DO NOT CITE 2 Acknowledgements I would like to thank the following people for their support, advice and openness in helping me complete this research paper: Gilles Bisson Sean Conway Steve Gilchrist Henry Jacek Sylvia Jones Rosario Marchese Lynn Morrison Graham Murray David Ramsay Greg Sorbara Lise St-Denis David Warner Graham White 3 INTRODUCTION When the October 2011 Ontario general election saw Premier Dalton McGuinty’s Liberals win a “major minority”, there was speculation at Queen’s Park that a Member of Provincial Parliament (MPP) from the Progressive Conservative (PC) Party or New Democratic Party (NDP) would be induced to cross the floor. The Liberals had captured fifty-three of 107 seats; the PCs and NDP, thirty-seven and seventeen, respectively. A Member of one of the opposition parties defecting to join the Liberals would have definitively changed the balance of power in the Legislature. Even with the Speaker coming from the Liberals’ ranks, a floor crossing would give the Liberals a de facto majority and sufficient seats to drive forward their legislative agenda without having to rely on at least one of the opposition parties. A January article in the Toronto Star revealed that the Liberals had quietly made overtures to at least four PC and NDP MPPs since the October election, 1 meaning that a floor crossing was a very real possibility. -

Ottawa No Sweat

City of Ottawa Ottawa No Sweat Email Contact List Ottawa No Sweat is a coalition of individuals Ward 1 - Herb Kreling and representatives from faith, labour, [email protected] student, and non-governmental Ward 2 - Rainer Bloess organizations. We are concerned about [email protected] working conditions in sweatshops around Ward 3 - Jan Harder [email protected] the world. Ward 4 - Peggy Feltmate [email protected] Ottawa No Sweat is part of the Ethical Trading Ward 5 - Eli El-Chantiry Action Group (ETAG). ETAG is lobbying [email protected] to get Canadian public institutions to adopt Ward 6 - Janet Stavinga ethical purchasing policies and mobilizing [email protected] for changes to federal textile labeling Ward 7 - Alex Cullen regulations. [email protected] Ward 8 - Rick Chiarelli Ottawa No Sweat is working to get the City of [email protected] Ward 9 - Gord Hunter Ottawa to adopt a ‘No Sweat’ ethical [email protected] purchasing policy. A ‘No Sweat’ ethical Ward 10 - Diane Deans purchasing policy will ensure that clothing [email protected] and other goods purchased by the City of Ward 11 - Michel Bellemare Ottawa are not produced in sweatshop [email protected] Ward 12 - Georges Bédard conditions. [email protected] The City of Ottawa Ward 13 - Jacques Legendre [email protected] shouldn’t be Ward 14 - Diane Holmes [email protected] Ward 15 - Shawn Little supporting [email protected] Ward 16 - Maria McRae sweatshops with our [email protected] Contact your City Councillor City Contact your Ward 17 - Clive Doucet [email protected] tax dollars. -

Building the Future Provides the Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada with House of Commons Requirements

Building the Future provides the Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada with House of Commons requirements for planning and implementing the long-term renovation and development of the Parliamentary Precinct. BuildingBuilding thethe FutureFuture House of Commons Requirements for the Parliamentary Precinct October 22, 1999 ii Building the Future Table of Contents Preface . v Foreword . .vii Executive Summary . ix The Foundation . 1 A. Historical Considerations . 2 B. Current and Future Considerations . 6 C. Guiding Principles . 8 Requirements for Members’ Lines of Business . 9 Chamber . .10 Committee . .14 Caucus . .24 Constituency . .28 Requirements for Administration and Precinct-wide Support Services . .33 Administration and Support Services . .34 Information Technology . .38 Security . .43 Circulation . .47 The Press Gallery . .51 The Visiting Public . .53 Requirements for Implementation . .55 A. A Management Model . .56 B. Use of Buildings . .58 C. Renovation Priorities . .59 Moving Ahead: Leaving a Legacy . .65 Appendix A: Past Planning Reports . .67 Appendix B: Bibliography . .71 Building the Future iii iv Building the Future Preface I am pleased to submit Building the Future: House of Commons Requirements for the Parliamentary Precinct to the Board of Internal Economy. The report sets out the broad objectives and specific physical requirements of the House of Commons for inclusion in the long-term renovation and development plan being prepared by Public Works and Government Services Canada. In preparing this report, the staff has carefully examined the history of the Precinct to ensure that our focus on the future benefits from the expertise and experiences of the past. Moreover, this work strongly reflects the advice of today’s Members of Parliament in the context of more recent reports, reflections and discussions since the Abbott Commission’s Report in 1976. -

Birchall Leadership Award 2020

BIRCHALL LEADERSHIP AWARD 2020 The Royal Military Colleges Foundation in partnership with True Patriot Love Foundation’s Captain Nichola Goddard Fund Calgary, Alberta March 9, 2020 MEDIA ADVISORY Prestigious Leadership Award to be Presented to Olympian Beckie Scott in Calgary Calgary, AB – Beckie Scott, an internationally-recognized leader in sport and an Olympic gold medalist in cross country skiing, one of Canada’s modern heroes, will be honoured in Calgary on March 9, 2020 with the prestigious Birchall Leadership Award, created in honour of a Canadian World War II hero, 2364 Air Commodore Leonard Birchall. The Award will be presented at True Patriot Love Foundation's Captain Nichola Goddard Roundtable and Reception hosted by Bennett Jones LLP. Ms. Scott has served as an athletes’ representative at the highest level of international sport and is recognized globally for her efforts on behalf of clean, fair doping-free sport and athletes’ rights. Beckie Scott exemplifies Air Commodore Birchall’s qualities including the ability to lead in the face of difficulty or adversity to promote the welfare and safety of others. The Birchall Leadership Award is presented biennially by the Royal Military Colleges Foundation to a deserving Canadian to honour the memory of 2364 Air Commodore Leonard Birchall (1915-2004), who was an exemplary leader during World War II in combat and in prisoner of war camps, and post-war as a senior RCAF commander. Air Commodore Birchall, while pilot of an RCAF Canso seaplane on April 4th, 1942, spotted a Japanese raiding fleet off the coast of Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). His report allowed a Royal Navy fleet to save most of their ships and reduce damage to bases on the island. -

Volume 33 Number 7

November 7, 2003 r- glebe report t9, raei-sor ebe 7, 2003 November Vol. 33 No. 10 Serving the Glebe community since 1973 FREE New 40 km/h speed limit for the Glebe! 40 km/ h Illustration: Gwendolyn Best BY WAYNE BURGESS glebeonline.ca at the GCA website; On Oct. 8, Ottawa City Council e-mail or write or fax Ravi Mehta, passed Clive Doucet's motion for a Senior Project Engineer at the City 40 km/h speed limit in the Glebe. of Ottawa, at [email protected], Now you see it Restricting the speed of traffic and and send a copy to councillor Clive reducing the volume of traffic flow Doucet at [email protected], through the Glebe have always been and to Mayor Bob Chiarelli at Bob. and still are the two linchpins of the [email protected]. E-mail, write Glebe Traffic Plan. or fax all city councillors and let the Thanks largely to Clive Doucet's city know that the residents of the tireless and single-minded efforts, Glebe WANT the Glebe Traffic Plan one of the two objectives of the adopted and implemented as pre- Glebe Traffic Plan has been realized. sented! E-mail or write or fax them It is worth noting this is a neighbour- often. hood-wide solution. All of the Glebe The Plan will not go to city coun- benefits. cil until after the next municipal The second linchpin, restricting election. Below is a list of the current the amount of traffic flow through city councillors. Clearly, a few will the Glebe, is yet to be achieved. -

2018 Annual Report True Patriot Love Foundation Strengthening Military and Veteran Families

2018 ANNUAL REPORT TRUE PATRIOT LOVE FOUNDATION STRENGTHENING MILITARY AND VETERAN FAMILIES. TABLE OF CONTENTS 4 Letter to Supporters 6 About True Patriot Love Foundation 7 Our Impact 22 Financial Statements 23 Funding Recipients 25 2018 Donors 26 Process, Governance & Structure TRUE PATRIOT LOVE 2018 ANNUAL REPORT 3 Letter to Supporters Dear Friends of True Patriot Love, Late in 2018, we said goodbye to CEO Bronwen Evans who, along with her team, We are very pleased to present True Patriot Love built True Patriot Love from the ground Foundation’s 2018 Annual Report, which reflects a milestone up and into the largest organization of year for the foundation in many ways. its kind in Canada. We thank Bronwen for all her hard work and dedication to our cause. As she stepped down, we In 2018, we continued to focus on driving national impact for military were pleased to welcome Nick Booth, a members, Veterans and their families, committing more than $3.2 million to seasoned leader in the charitable sector, help fund 75 programs and services across Canada. This report recognizes the who has robust international experience, impactful, innovative work being done by many of our program partners. The which includes being the founding CEO True Patriot Love team knows that our work would not be possible without the of The Royal Foundation and an initiator generous backing of our donors and supporters, so thank you, most sincerely, of the Invictus Games. As we enter our for helping us change lives. second decade, Nick and the team are In November, we celebrated our tenth Tribute Gala – the largest event of its well poised to take True Patriot Love to kind that honours the brave men and women who have served our nation. -

A Study of Canada's Centennial Celebration Helen Davies a Thesis

The Politics of Participation: A Study of Canada's Centennial Celebration BY Helen Davies A Thesis Subrnitted to the Facuity of Graduate Studies in Partial Fultiiment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Histop University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba G Copyright September 1999 National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1+1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Weilington Street 395. rue Wellington Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Cntawa ON Kf A ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or seil reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of ths thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la fome de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be p~tedor otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. THE UNIVERSITY OF MANITOBA FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES ***** COPYRIGHT PERMISSION PAGE The Poiitics of Participation: A Study of Camdi's Centennid Celebntion by Helen Davies A Thesis/Practicum submitted to the Facalty of Gnduate Studics of The University of Manitoba in partial fiilfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Pbüosophy Helen Davies O 1999 Permission bas been gnnted to the Librrry of The University of Manitoba to lend or seIl copies of this thesis/practicum, to the National Librrry of Canada to microfilm this thesis/practicum and to lend or seil copies of the film, and to Dissertations Abstracts International to publish an abstrrct of this thesidpracticum. -

Captain Nichola Goddard Leadership Series Presented by Bennett Jones

CAPTAIN NICHOLA GODDARD LEADERSHIP SERIES PRESENTED BY BENNETT JONES VANCOUVER - MARCH 10, 2020 5:00 p.m. - 7:30 p.m. SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITIES Charitable Registration Number: 81464 6493 RR0001 CAPTAIN NICHOLA GODDARD LEADERSHIP SERIES: SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITIES ABOUT THE EVENT Captain Nichola Goddard Leadership Series - Vancouver Tuesday, March 10, 2020 Bennett Jones 666 Burrard St #2500, Vancouver, BC V6C 2X8 The Vancouver edition of the Captain Nichola Goddard Leadership Series, presented by Bennett Jones, will feature a panel discussion with a group of remarkable women from the Canadian Armed Forces, focusing on the themes of resilience and agility in leadership. Bringing together military members, business leaders and community partners, the reception will provide insight and generate inspiring discussion surrounding the unique experiences women face in the Canadian Armed Forces. Speakers will share inspirational stories of courage, leadership and resiliency while speaking to how their military careers have shaped and defined them. Meet & greet Panel discusssion Networking with Q&A period 5:00 p.m. - 6:00 p.m. 6:00 p.m. - 7:00 p.m. 7:00 p.m. - 7:30 p.m. For more information, to purchase single tickets, or to make a donation please visit: www.truepatriotlove.com/goddard-reception-2020/ For questions and to secure your involvement, please contact: Meighan Bell Chief Development Officer [email protected] or call 647.608.6940 True Patriot Love Foundation True Patriot Love Foundation is a national charity that is changing the lives of military members, Veterans and their families across Canada. By funding more than 825 programs that support mental health, physical rehabilitation, transition to life after service, and the unique needs of children and families, we’ve helped 30,000 military and Veteran families in need over the past decade. -

The Veteran's Voice

The Veteran’s Voice Throughout her life, Joyce converted the old World Allen has held many titles: War Two Lancaster Bombers mother, grandmother, past into full-fledged spy planes. The member of the board of bomb-bay doors became “bulb-bay” governors at the University of doors, and were retrofitted with up to 25 cameras snapping Winnipeg, lifelong learner, a photographs at a time, in order to provide images of as large a citizen first of Britain and later territory as possible. The ultimate objective: to monitor the build- of Canada, and also a proud up of Russian military installations and to track Soviet activities Manitoban. But as MSBA on land and at sea. discovered during our latest “Veteran’s Voice” Interview, Beyond these few details concerning her service however, Joyce Joyce is also a veteran. remains tight-lipped. Some secrets are simply not meant to be shared, even to this day. If there was one revelation from our Joyce Allen As a young child growing up interview however, it was that for every “James Bond” employed during the final years of the by Great Britain during the Cold War, there was also a Joyce Allen! Second World War, she well recalls the need to seek refuge in air raid shelters as German rockets rained down on civilians, killing We would encourage all Manitobans to watch our video over 50,000 of her fellow Britons. This experience motivated interview with Joyce, to learn more about her thoughts on Joyce to serve her country, even with the war at a close. -

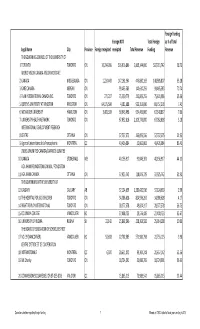

Canadian-Charities-Table-A.Pdf

Foreign Funding Foreign NOT Total Foreign as % of Total Legal Name City Province Foreign receipted receipted Total Revenue Funding Revenue THE GOVERNING COUNCIL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF 1 TORONTO TORONTO ON 10,294,936 526,916,806 2,865,144,000 537,211,742 18.75 WORLD VISION CANADA‐VISION MONDIALE 2 CANADA MISSISSAUGA ON 1,224,443 147,161,364 445,830,169 148,385,807 33.28 3 CARE CANADA NEPEAN ON 99,465,583 140,610,259 99,465,583 70.74 4 PLAN INTERNATIONAL CANADA INC. TORONTO ON 271,207 75,330,779 213,809,255 75,601,986 35.36 5 QUEEN'S UNIVERSITY AT KINGSTON KINGSTON ON 64,175,590 4,581,688 923,353,036 68,757,278 7.45 6 MCMASTER UNIVERSITY HAMILTON ON 3,405,339 63,943,498 954,409,000 67,348,837 7.06 7 UNIVERSITY HEALTH NETWORK TORONTO ON 67,052,818 2,105,776,000 67,052,818 3.18 INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT RESEARCH 8 CENTRE OTTAWA ON 57,737,575 263,099,556 57,737,575 21.95 9 Agence Universitaire de la Francophonie MONTREAL QC 43,426,084 52,062,002 43,426,084 83.41 DUCKS UNLIMITED CANADA/CANARDS ILLIMITES 10 CANADA STONEWALL MB 40,156,917 91,046,301 40,156,917 44.11 AGA KHAN FOUNDATION CANADA / FONDATION 11 AGA KHAN CANADA OTTAWA ON 37,925,742 118,879,729 37,925,742 31.90 THE GOVERNORS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF 12 CALGARY CALGARY AB 37,124,639 1,280,420,916 37,124,639 2.90 13 THE HOSPITAL FOR SICK CHILDREN TORONTO ON 34,386,628 824,936,261 34,386,628 4.17 14 RIGHT TO PLAY INTERNATIONAL TORONTO ON 28,277,578 49,824,317 28,277,578 56.75 15 COLUMBIA COLLEGE VANCOUVER BC 27,408,723 29,576,489 27,408,723 92.67 16 UNIVERSITY OF REGINA REGINA SK 22,142 25,892,096 258,363,582 25,914,238 10.03 THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF SCHOOL DISTRICT 17 NO.