Hospital Services in the Mid-Sussex

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minutes South Mid Sussex County Local Committee 26 November 2013

Agenda Item No. 3 South Mid Sussex County Local Committee 26 November 2013 – At a meeting of the Committee held at 7pm, Downlands Community School, Dale Avenue, Hassocks, BN6 8LP Present: Mr Barrett-Miles, Mr Griffiths (Chairman), Mrs Jones and Mr Petch. Welcome and Introductions 57. The Headteacher of Downlands Community School welcomed the Committee to the school. 58. The Chairman invited members of the Committee to introduce themselves and welcomed all to the meeting. Declarations of Interest 59. None Minutes 60. Resolved – that the minutes of the meeting of the Committee held on 10 September 2013 be approved as a correct record and that they be signed by the Chairman. Urgent Matters 61. None Progress Statement 62. The Principal Community Officer informed members that of the six parishes within the South Mid Sussex CLC area that had applied for Operation Watershed funding, Albourne, Poynings, Fulking and Twineham and Pyecombe had been successful and total allocations amounted to £50-60k. The successful parish councils would now work with their contractor of choice to deliver the works. Bolney Parish Council, which had been unsuccessful, was currently revising its application prior to resubmission. 63. The Principal Community Officer provided members with updates for currently progressing TROs in the CLC area in advance of setting Traffic Regulation Order priorities at the Committee’s next meeting. He also informed members that across the county a number of school safety zones were currently unenforceable and that officers were currently consulting on how these TROs would be delivered. Talk with Us Open Forum 64. The Chairman invited questions and comments from members of the public, which included: • A local resident sought the Committee’s support for traffic calming measures in Keymer, which were required owing to speeding vehicles and the potentially dangerous road layout. -

The Main Changes to Compass Travel's Routes Are

The main changes to Compass Travel’s routes are summarised below. 31 Cuckfield-Haywards Heath-North Chailey-Newick-Maresfield-Uckfield The additional schooldays only route 431 journeys provided for Uckfield College pupils are being withdrawn. All pupils can be accommodated on the main 31 route, though some may need to stand between Maresfield and Uckfield. 119/120 Seaford town services No change. 121 Lewes-Offham-Cooksbridge-Chailey-Newick, with one return journey from Uckfield on schooldays No change 122 Lewes-Offham-Cooksbridge-Barcombe Minor change to one morning return journey. 123 Lewes-Kingston-Rodmell-Piddinghoe-Newhaven The additional schooldays afternoon only bus between Priory School and Kingston will no longer be provided. There is sufficient space for pupils on the similarly timed main service 123, though some may need to stand. There are also timing changes to other journeys. 125 Lewes-Glynde-Firle-Alfriston-Wilmington-District General Hospital-Eastbourne Minor timing changes. 126 Seaford-Alfriston No change. 127/128/129 Lewes town services Minor changes. 143 Lewes-Ringmer-Laughton-Hailsham-Wannock-Eastbourne The section of route between Hailsham and Eastbourne is withdrawn. Passengers from the Wannock Glen Close will no longer have a service on weekdays (Cuckmere Buses routes 125 and 126 serve this stop on Saturdays and Sundays). Stagecoach routes 51 and 56 serve bus stops in Farmlands Way, about 500 metres from the Glen Close bus stop. A revised timetable will operate between Lewes and Hailsham, including an additional return journey. Stagecoach provide frequent local services between Hailsham and Eastbourne. 145 Newhaven town service The last journey on Mondays to Fridays will no longer be provided due to very low use. -

Local Defibrillators Fulking

Local Defibrillators If you are planning a cardiac event then it makes sense (i) to have it in a location that has a defibrillator available, (ii) to have with you a companion who knows exactly where the defibrillator is, and (iii) for that companion to have some idea how to use it. The text, maps, and photos on this webpage are intended to facilitate the first two goals. With regard to the third goal, modern public access defibrillators are designed to be usable without prior instruction (they talk you through the process) but your companion will feel much more confident about saving your life if they have attended one of the many defibrillator and resuscitation courses on offer locally. Contact HART to discover times and locations. Finally, you can encourage your companion to do some relevant reading. Fulking The Fulking defibrillator is in the centre of the village. The red door to the right is the entrance to the green corrugated iron shack that has served as the village hall for the last ninety years. The porch to the left is the entrance to a tiny brick chapel now used as the church bookstore. The defibrillator is in this porch and is accessible 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Edburton The Edburton defibrillator is located at Coles Automotive which is at the end of Browns Meadow, a track that begins roughly opposite to Springs Smoked Salmon. It is kept in their reception area and is thus only accessible during garage opening hours. Poynings: The Forge Garage Poynings has two defibrillators. -

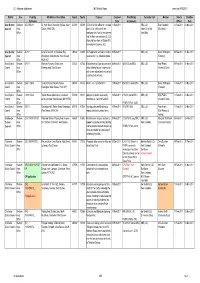

Local Development Division Planning Applications

LD - Allocated Applications MIS Weekly Report week start 07/02/2011 District Area Planning Site Address Description Xpoint Ypoint Proposal Received Prev.History Consultee / LO Member Date to Deadline Reference Date & Comments Officer Date Adur District Southern ADC/0052/11 70, High Street, Shoreham-by-Sea, West 521391 105066 COU of 1st floor offices to 1 x 2-bed 11-Feb-2011 - SRU (LO) Brian Coomber 11-Feb-2011 04-Mar-2011 Council Area Sussex, BN43 5DB flat (C3 1-4) with room in the Adam Ch (s106) (Shoreham) Office roofspace (incl. front & rear dormers John Mills and 1st floor rear extension) & COU of ground floor from Art Studio (A1) to employment agency (A2). Arun District Western AL/7/11 Land To Rear Of, 31, Meadow Way, 493842 104835 OUT application with some matters 08-Feb-2011 - SRU (LO) Derek Whittington 09-Feb-2011 01-Mar-2011 Council Area Westergate, Aldingbourne, West Sussex, reserved for 1 no. 2 bed bungalow. (Fontwell) Office PO20 3QT Arun District Western W/1/11 Yeomans Nursery, Sefton Lane, 503122 107322 Replacement of 2 glasshouses with 08-Feb-2011 W/5/10 (Liam/SRU) SRU (LO) Nigel Peters 09-Feb-2011 01-Mar-2011 Council Area Warningcamp, West Sussex office building for use in connection (Arundel & Wick) Office with current educational units on site & horticultural activities. Arun District Western EG/2/11/DOC Hunters Chase, Fontwell Avenue, 494806 106314 DOC 3, 4 & 12 of EG/15/10. 10-Feb-2011 EG/15/10 (Jamie/SRU) SRU (LO) Derek Whittington 11-Feb-2011 03-Mar-2011 Council Area Eastergate, West Sussex, PO20 3RY (Fontwell) Office Arun District Western LY/3/11/DOC Thelton House Apartments, Crossbush 503309 106011 Approval of details reserved by 10-Feb-2011 LY/2/10 (Jamie/SRU) SRU (LO) Nigel Peters 11-Feb-2011 03-Mar-2011 Council Area Lane, Lyminster, West Sussex, BN18 9PQ conditions 2, 3 and 4 of LY/2/10. -

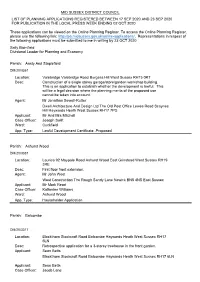

Mid Sussex District Council List of Planning Applications Registered Between 17 Sep 2020 and 23 Sep 2020 for Publication in the Local Press Week Ending 02 Oct 2020

MID SUSSEX DISTRICT COUNCIL LIST OF PLANNING APPLICATIONS REGISTERED BETWEEN 17 SEP 2020 AND 23 SEP 2020 FOR PUBLICATION IN THE LOCAL PRESS WEEK ENDING 02 OCT 2020 These applications can be viewed on the Online Planning Register. To access the Online Planning Register, please use the following link: http://pa.midsussex.gov.uk/online-applications/. Representations in respect of the following applications must be submitted to me in writing by 23 OCT 2020 Sally Blomfield Divisional Leader for Planning and Economy Parish: Ansty And Staplefield DM/20/3361 Location: Valebridge Valebridge Road Burgess Hill West Sussex RH15 0RT Desc: Construction of a single storey garage/store/garden workshop building. This is an application to establish whether the development is lawful. This will be a legal decision where the planning merits of the proposed use cannot be taken into account. Agent: Mr Jonathan Sewell-Rutter Dwell Architecture And Design Ltd The Old Post Office Lewes Road Scaynes Hill Haywards Heath West Sussex RH17 7PG Applicant: Mr And Mrs Mitchell Case Officer: Joseph Swift Ward: Cuckfield App. Type: Lawful Development Certificate -Proposed Parish: Ashurst Wood DM/20/3337 Location: Laurica 92 Maypole Road Ashurst Wood East Grinstead West Sussex RH19 3RE Desc: First floor front extension. Agent: Mr John West West Construction The Rough Sandy Lane Newick BN8 4NS East Sussex Applicant: Mr Mark Read Case Officer: Katherine Williams Ward: Ashurst Wood App. Type: Householder Application Parish: Balcombe DM/20/3317 Location: Blackthorn Stockcroft Road Balcombe Haywards Heath West Sussex RH17 6LN Desc: Retrospective application for a 3-storey treehouse in the front garden. -

Mid Sussex Matters 95

NEWS AND FEATURES FROM MID SUSSEX DISTRICT COUNCIL www.midsussex.gov.uk | Issue 95 Winter 2018 Winter 95 | Issue www.midsussex.gov.uk KEEPING ACTIVE AND CONNECTED throughout Mid Sussex 6 Community Service Award winners and WIN festive waste and recycling day changes + TravelodgePanto Break tickets & Chrati Dsrutsillmas as from Saturday 17th November 2018 Meet Father Christmas A meet-and-greet experience that includes a quality gift (see website for dates, times and prices) The Husky Cave You’d be barking mad to miss it! (see website for dates and times) Christmas Lights Daily from Saturday 17th November - Tuesday 1st January Hello Kitty Parlour Pop into the Parlour for seasonal activities including Christmas face painting and tattoos (see website for dates and times) Festive Food Enjoy a glass of mulled wine and delicious mince pies Book your tickets ONLINE in advance and SAVE 10% www.drusillas.co.uk Check out the details at www.drusillas.co.uk At Alfriston just off the A27 near Eastbourne Call: 01323 874100 LOCAL NEWS 4/5 Mid Sussex Matters is sent to all residents WELLBEING MATTERS 6/7 and provides you with COMMUNITY SERVICE information about our AWARDS 8/9 services. Published by in this issue... the Communications GRANTS 10 Team, Mid Sussex District Council, Oaklands Road, BUSINESS MATTERS 11 Haywards Heath, West BURGESS HILL GROWTH Sussex RH16 1SS. PROGRAMME 12/13 Design by Sublime: www.wearesublime.com COMMUNITY HOMES MATTER 15 SERVICE AWARDS / 8 Printed by Storm Print & Design: FIGHT AGAINST FOOD WASTE 16 www.stormprintanddesign.co.uk FESTIVE WASTE & 72,000 copies are distributed RECYCLING 17 free to Burgess Hill, East Grinstead, Haywards Heath and WINTER MATTERS 18 Mid Sussex villages. -

Consultation Statement

Haywards Heath Town Centre Masterplan Supplementary Planning Document Consultation Statement April 2021 1. Introduction 1.1. This Consultation Statement has been prepared in accordance with Regulation 12 of the Town and Country Planning (Local Planning) (England) Regulations 2012. 2. Public consultation 2.1. At its meeting of 22nd October 2020, the Scrutiny Committee for Housing, Planning and Economic Growth considered a draft Haywards Heath Town Centre Masterplan (the draft Masterplan). The Committee agreed unanimously that the Cabinet Member for Housing and Planning approve the document for public consultation. 2.2. The following documents were made available during the consultation period: • Draft Haywards Heath Town Centre Masterplan SPD • Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) Screening Report • Consultation notice • Community Involvement Plan • Equalities Impact Assessment 2.3. Public consultation was held for 6 weeks between 9th November – 21st December 2020. The consultation was carried out in accordance with the Council’s adopted Statement of Community Involvement (SCI) and the Community Involvement Plan (CIP). 2.4. This included: • publishing the details on the Council’s website, • Notification using the Council’s social media feeds (Facebook and Twitter) • providing an interactive map facility to view the proposals – this was viewed over 7,500 times, • an email and letter notification to statutory consultees and those on the Council’s consultation mailing list. This includes both organisations and individuals/residents – a list of organisations contacted is in Appendix 1. • a press release and coverage in local newspapers such as the Mid Sussex Times, and • an article in the Council’s magazine (Mid Sussex Matters) which is delivered to every household within the district. -

Made HNP July 2020.Pages

Hassocks Neighbourhood Plan 2014 - 2031 Made Version: July 2020 Page Left Intentionally Blank Hassocks Neighbourhood Plan - Made Version Contents Page Foreword (i) 1. Introduction 2 2. Parish Profile 6 3. Vision and Objectives 13 4. Environment and Heritage 16 Policy 1: Local Gaps 16 Policy 2: Local Green Spaces 19 Policy 3: Green Infrastructure 21 Policy 4: Managing Surface Water 22 Policy 5: Enabling Zero Carbon 24 Policy 6: Development Proposals Affecting the South Downs National Park 25 Policy 7: Development in Conservation Areas 26 Policy 8: Air Quality Management 28 Policy 9: Character and Design 29 5. Community Infrastructure 32 Policy 10: Protection of Open Space 32 Policy 11: Outdoor Play Space 34 Policy 12: Community Facilities 35 Aim 1: Assets of Community Value 36 Policy 13: Education Provision 37 Aim 2: Education Facilities 37 Aim 3: Healthcare Facilities 38 6. Housing 40 Policy 14: Residential Development Within and Adjoining the Built-Up Area Boundary of Hassocks 42 Policy 15: Hassocks Golf Club 43 Policy 16: Land to the North of Clayton Mills and Mackie Avenue 44 Aim 4: Housing Mix 46 Policy 17: Affordable Housing 47 7. Economy 50 Policy 18: Village Centre 50 Policy 19: Tourism 51 Hassocks Neighbourhood Plan - Made Version 8. Transport 54 Aim 5: Non-Car Route Ways 54 Aim 6: Public Transport 56 Aim 7: Traffic and Accessibility 57 9. Implementation and Delivery 60 10. Policies Map 62 11. Evidence Base 66 Hassocks Neighbourhood Plan - Made Version FOREWORD This Plan has been the subject of seven years of work by a team comprising Parish Councillors and Co-opted Residents and during this protracted plan-making process the Parish has had to face a series of very challenging issues. -

Burgess Hill Character Assessment Report

Burgess Hill Historic Character Assessment Report November 2005 Sussex Extensive Urban Survey (EUS) Roland B Harris Burgess Hill Historic Character Assessment Report November 2005 Roland B Harris Sussex Extensive Urban Survey (EUS) in association with Mid Sussex District Council and the Character of West Sussex Partnership Programme Sussex EUS – Burgess Hill The Sussex Extensive Urban Survey (Sussex EUS) is a study of 41 towns undertaken between 2004 and 2008 by an independent consultant (Dr Roland B Harris, BA DPhil MIFA) for East Sussex County Council (ESCC), West Sussex County Council (WSCC), and Brighton and Hove City Council; and was funded by English Heritage. Guidance and web-sites derived from the historic town studies will be, or have been, developed by the local authorities. All photographs and illustrations are by the author. First edition: November 2005. Copyright © East Sussex County Council, West Sussex County Council, and Brighton and Hove City Council 2005 Contact: For West Sussex towns: 01243 642119 (West Sussex County Council) For East Sussex towns and Brighton & Hove: 01273 481608 (East Sussex County Council) The Ordnance Survey map data included within this report is provided by West Sussex County Council under licence from the Ordnance Survey. Licence 100018485. The geological map data included within this report is reproduced from the British Geological Map data at the original scale of 1:50,000. Licence 2003/009 British Geological Survey. NERC. All rights reserved. The views in this technical report are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of English Heritage, East Sussex County Council, West Sussex County Council, Brighton & Hove City Council, or the authorities participating in the Character of West Sussex Partnership Programme. -

SUSSEX. Hawken Giles Lockwoodlangm.R.C.S

474 BURSTPJ !RPOINT I SUSSEX. Hawken Giles LockwoodLangM.R.C.S. Marshall Walter, grocer, Western rd Russell Arth.Reuben,irnmngr.High st Eng.,L.S.A. surgeon (firm, Hawken Masters & Tulley, family grocers, St. Christopher's Home for the Aged, & Beach), Eastern house drapers, house furnishers & house Cuckfield road Hayes Ernest, greengrocer, 7 Church agents, The Stores, High street & St. John's College (Rev. Arthur Henry Coombes M.A. head master; E. E. terrace, High street Keviner• road, Hassocks Heathorn Fredk. Jn. baker, High st Maury Camille (Mdlle. )_, girls' school, Balshaw, sec) Heaton Geo. Edward M.P.S. chemist, see Heron May (:Miss) & 2\'Iaury Salcombe William, Chinese Gardens High street Camille (~dlle) P.H. Western road Render Bernard Brooks, farmer, }litten & Co. cl~emists (Arnold Shove Charles, masseur, Thistledene, Little park Spencer Whitby :\<LP.S.U:md.), West ern Toad Heron ~lay (Miss) & Maury Camille High street Simmons John, beer retlr. High st (Mdlle. ), girls' school, Belle Vue ~loon; Edward. iusurance agent, 3 Sims William Edward, photographer, house, Cuckfield road Cards place, High street Hassocks'road Hersee William Charles, Sussex Arms Morley J. N. & !Son, bakers, High st Smith ..A.lbert W. confectioner, Stanley P.H. Cuckfield road M01·ley Lawrence, farm bailiff to house, High street Holden Fredk. tobacconist, High st Reuben Scrase esq. Dumbrell farm Smith Harry, auctioneer, Ruckford Hole Amos, higgler, Sayers Colliroon Myall Henry, baker, Cuckfield road Smith John Edwin, saddler, High st Hole Edwin, blacksmith, Sayers Com .\-lyram William, farmer, Leigh farm Smithers & Sons Limited, brewers, Hole Fredk. pig killer, Sayers Com (letters via Cuckfield) Cuckfield road Hole John, shopkeeper, Sayers Corn ~ayworth Cottage Convalescent Home Spong- A. -

Planning Applications Received 08 Aug to 14 Aug 2019

MID SUSSEX DISTRICT COUNCIL LIST OF PLANNING APPLICATIONS REGISTERED BETWEEN 08 AUG 2019 AND 14 AUG 2019 FOR PUBLICATION IN THE LOCAL PRESS WEEK ENDING 23 AUG 2019 These applications can be viewed on the Online Planning Register, and from computers available at the Council's Planning Services Reception, Oaklands, Oaklands Road, Haywards Heath, during normal office hours. To access the Online Planning Register, please use the following link: http://pa.midsussex.gov.uk/online-applications/. Representations in respect of the following applications must be submitted to me in writing by 06 SEP 2019 Sally Blomfield Divisional Leader for Planning and Economy Parish: Ansty And Staplefield DM/18/5114 Location: Burgess Hill Northern Arc Land North And North West Of Burgess Hill Between Bedelands Nature Reserve In The East And Goddard's Green Waste Water Treatment Works In The West Desc: Comprehensive, phased, mixed-use development comprising approximately 3,040 dwellings including 60 units of extra care accommodation (Use Class C3) and 13 permanent gypsy and traveller pitches, including a Centre for Community Sport with ancillary facilities (Use Class D2), three local centres (comprising Use Classes A1-A5 and B1, and stand-alone community facilities within Use Class D1), healthcare facilities (Use Class D1), and employment development comprising a 4 hectare dedicated business park (Use Classes B1 and B2), two primary school campuses and a secondary school campus (Use Class D1), public open space, recreation areas, play areas, associated infrastructure including pedestrian and cycle routes, means of access, roads, car parking, bridges, landscaping, surface water attenuation, recycling centre and waste collection infrastructure with associated demolition of existing buildings and structures, earthworks, temporary and permanent utility infrastructure and associated works. -

The Economic Geography of the Gatwick Diamond

The Economic Geography of the Gatwick Diamond Hugo Bessis and Adeline Bailly October, 2017 1 Centre for Cities The economic geography of the Gatwick Diamond • October, 2017 About Centre for Cities Centre for Cities is a research and policy institute, dedicated to improving the economic success of UK cities. We are a charity that works with cities, business and Whitehall to develop and implement policy that supports the performance of urban economies. We do this through impartial research and knowledge exchange. For more information, please visit www.centreforcities.org/about About the authors Hugo Bessis is a Researcher at Centre for Cities [email protected] / 0207 803 4323 Adeline Bailly is a Researcher at Centre for Cities [email protected] / 0207 803 4317 Picture credit “Astral Towers” by Andy Skudder (http://bit.ly/2krxCKQ), licensed under Creative Commons (CC BY-SA 2.0) Supported by 2 Centre for Cities The economic geography of the Gatwick Diamond • October, 2017 Executive Summary The Gatwick Diamond is not only one of the South East’s strongest economies, but also one of the UK’s best performing areas. But growth brings with it a number of pressures too, which need to be managed to maintain the success of the area. This report measures the performance of the Gatwick Diamond relative to four comparator areas in the South East, benchmarking its success and setting out some of the policy challenges for the future. The Gatwick Diamond makes a strong contribution to the UK economy. It performs well above the national average on a range of different economic indicators, such as its levels of productivity, its share of high-skilled jobs, and its track record of attracting foreign investment.