Burgess Hill Character Assessment Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uncontested Parish Election 2015

NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Horsham District Council Election of Parish Councillors for Parish of Amberley on Thursday 7 May 2015 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Parish of Amberley. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) ALLINSON Garden House, East Street, Hazel Patricia Amberley, Arundel, West Sussex, BN18 9NN CHARMAN 9 Newland Gardens, Amberley, Jason Rex Arundel, West Sussex, BN18 9FF CONLON Stream Barn, The Square, Geoffrey Stephen Amberley, Arundel, West Sussex, BN18 9SR CRESSWELL Lindalls, Church Street, Amberley, Leigh David Arundel, West Sussex, BN18 9ND SIMPSON Downlands Loft, High Street, Tim Amberley, Arundel, West Sussex, BN18 9NL UREN The Granary, East Street, Geoffrey Cecil Amberley, Arundel, West Sussex, BN18 9NN Dated Friday 24 April 2015 Tom Crowley Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Horsham District Council, Park North, North Street, Horsham, West Sussex, RH12 1RL NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Horsham District Council Election of Parish Councillors for Parish of Ashington on Thursday 7 May 2015 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Parish of Ashington. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) CLARK Spindrift, Timberlea Close, Independent Neville Ernest Ashington, Pulborough, West Sussex, RH20 3LD COX 8 Ashdene Gardens, Ashington, Sebastian Frederick -

NEIGHBOURHOOD DEVELOPMENT PLAN AUGUST 2015 (Including Post Exam Modifications)

BOGNOR REGIS 2015—2030 NEIGHBOURHOOD DEVELOPMENT PLAN AUGUST 2015 (including post exam modifications) I THE REPORT IS MADE ACCESSIBLE AT THIS WEBSITE: WWW.BOGNORREGIS.GOV.UK/BR-TOWN-COUNCIL/NEIGHBOURHOOD_PLAN-16104.ASPX This document has been produced by Bognor Regis Town Council’s Neighbourhood Plan Committee with support from: Imagine Places, Royal Town Planning Institute/Planning Aid England, Locality, Integrated Urbanism, BPUD, the Prince’s Foundation for Building Community and - most importantly - the good people of Bognor Regis that have at various stages of the process so far contributed and helped to shape this plan. Disclaimer: This document is optimised for online viewing only. Please consider the environment before printing. Hardcopies are available for viewing at the Town Hall in Bognor Regis. II FOREWORD WELCOME TO THE BOGNOR REGIS NEIGHBOURHOOD DEVELOPMENT PLAN! Bognor Regis Town Council are very aware of the strength of feeling and loyalty towards the town and the oft-expressed view that many of its finer buildings have been lost over the years or replaced with ones of lesser architectural merit or inappropriately sited. The Town Council believe that having a Neighbourhood Plan in place will give local people much more say in the future planning of the town with regard to buildings and green spaces; their quality, look, feel, usage and location, as well as offering some protection to existing sites and buildings, much loved and valued by the community. The idea of Neighbourhood Plans initially came about because central government felt it important that local people had more of a say in what happened in their own town or village. -

Notice of Variation: On-Street Parking Charges 2021 Arun District

WEST SUSSEX COUNTY COUNCIL NOTICE OF VARIATION: ON-STREET PARKING CHARGES 2021 ARUN DISTRICT NOTICE is hereby given that West Sussex County Council in exercise of its powers under Section 46A Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984 and Regulation 25 of the Local Authorities Traffic Order (Procedure) (England and Wales) Regulations 1996 proposes to vary the Charges and Tariffs detailed in the Second Schedule of the West Sussex County Council (Arun District) (Parking Places and Traffic Regulation) (Consolidation) Order 2010. The following charges will be changed as shown from 4 January 2021: Parking Permits: Old Charge New Charge Bognor Regis CPZ 1st Resident Annual Permit £44.00 £46.00 Subsequent Resident Annual Permit £88.00 £92.00 1st Resident 6-month Permit £24.00 £25.00 Subsequent Resident 6-month permit £48.00 £50.00 Non-Resident Annual Permit £275.00 £282.00 Non-Resident 6-month permit £145.00 £149.00 Countywide permits £25.00 £26.00 Pay and Display parking charges: Old Charge New Charge Town Per 30 mins Per Hour Per 30 mins Per Hour Centre Area £0.55 £1.10 £0.60 £1.20 Marine Per 30 mins Per Hour Per 30 mins Per Hour Drive West £0.30 £0.60 £0.35 £0.70 Esplanade Per 30 mins Per Hour Per 30 Mins Per Hour £0.55 £1.10 £0.60 £1.20 Dispensation Notices: Permit Areas in Arun: Old Charge New Charge CPZ Permit Areas £10.00 per day/£60.00 £11.00 per day/£66.00 per week per week Pay and Display Areas: Old Charge New Charge Bognor Regis Town Centre £14.00 per day/£84.00 £16.00 per day/£96.00 per week per week The Esplanade £15.00 per day/90.00 per -

The Main Changes to Compass Travel's Routes Are

The main changes to Compass Travel’s routes are summarised below. 31 Cuckfield-Haywards Heath-North Chailey-Newick-Maresfield-Uckfield The additional schooldays only route 431 journeys provided for Uckfield College pupils are being withdrawn. All pupils can be accommodated on the main 31 route, though some may need to stand between Maresfield and Uckfield. 119/120 Seaford town services No change. 121 Lewes-Offham-Cooksbridge-Chailey-Newick, with one return journey from Uckfield on schooldays No change 122 Lewes-Offham-Cooksbridge-Barcombe Minor change to one morning return journey. 123 Lewes-Kingston-Rodmell-Piddinghoe-Newhaven The additional schooldays afternoon only bus between Priory School and Kingston will no longer be provided. There is sufficient space for pupils on the similarly timed main service 123, though some may need to stand. There are also timing changes to other journeys. 125 Lewes-Glynde-Firle-Alfriston-Wilmington-District General Hospital-Eastbourne Minor timing changes. 126 Seaford-Alfriston No change. 127/128/129 Lewes town services Minor changes. 143 Lewes-Ringmer-Laughton-Hailsham-Wannock-Eastbourne The section of route between Hailsham and Eastbourne is withdrawn. Passengers from the Wannock Glen Close will no longer have a service on weekdays (Cuckmere Buses routes 125 and 126 serve this stop on Saturdays and Sundays). Stagecoach routes 51 and 56 serve bus stops in Farmlands Way, about 500 metres from the Glen Close bus stop. A revised timetable will operate between Lewes and Hailsham, including an additional return journey. Stagecoach provide frequent local services between Hailsham and Eastbourne. 145 Newhaven town service The last journey on Mondays to Fridays will no longer be provided due to very low use. -

CHECK BEFORE YOU TRAVEL at Nationalrail.Co.Uk

Changes to train times Monday 7 to Sunday 13 October 2019 Planned engineering work and other timetable alterations King’s Lynn Watlington Downham Market Littleport 1 Ely Saturday 12 and Sunday 13 October Late night and early morning alterations 1 ! Waterbeach All day on Saturday and Sunday Late night and early morning services may also be altered for planned Peterborough Cambridge North Buses replace trains between Cambridge North and Downham Market. engineering work. Plan ahead at nationalrail.co.uk if you are planning to travel after 21:00 or Huntingdon Cambridge before 06:00 as train times may be revised and buses may replace trains. Sunday 13 October St. Neots Foxton Milton Keynes Bedford 2 Central Shepreth Until 08:30 on Sunday Sandy Trains from London will not stop at Harringay, Hornsey or Alexandra Palace. Meldreth Replacement buses will operate between Finsbury Park and New Barnet, but Flitwick Biggleswade Royston Bletchley will not call at Harringay or Hornsey. Please use London buses. Ashwell & Morden Harlington Arlesey Baldock Leighton Buzzard Leagrave Letchworth Garden City Sunday 13 October Hitchin Luton 3 Until 09:45 on Sunday Stevenage Tring Watton-at-Stone Key to colours Buses replace trains between Alexandra Palace and Stevenage via Luton Airport Parkway Luton Knebworth Hertford North. Airport Hertford North No trains for all or part of A reduced service will operate between Moorgate and Alexandra Palace. Welwyn North Berkhamsted Harpenden Bayford Welwyn Garden City the day. Replacement buses Cuffley 3 St. Albans City Hatfield Hemel Hempstead may operate. Journey times Sunday 13 October Kentish Town 4 Welham Green Crews Hill will be extended. -

Agenda and Business

BOGNOR REGIS TOWN COUNCIL TOWN CLERK Glenna Frost, The Town Hall, Clarence Road, Bognor Regis, West Sussex PO21 1LD Telephone: 01243 867744 E-mail: [email protected] Dear Sir/Madam, ONLINE MEETING OF THE POLICY AND RESOURCES COMMITTEE I hereby give you Notice that an Online Meeting of the Policy and Resources Committee of the Bognor Regis Town Council will be held at 6.30pm on TUESDAY 19th JANUARY 2021 in accordance with The Local Authorities (Coronavirus) (Flexibility of Local Authority Meetings) (England) Regulations 2020. All Members of the Policy and Resources Committee are HEREBY SUMMONED to attend for the purpose of considering and resolving upon the business to be transacted as set out hereunder. The public will not be permitted to speak during the Meeting. However, an opportunity will be afforded to Members of the Public to have Questions put, or make Statements to, the Committee during an adjournment shortly after the meeting has commenced. NB: All Questions and Statements MUST be submitted in writing (preferably by email) and MUST be received by the Town Clerk before 9am on Tuesday 19th January 2021. Online access to the Meeting will be via ZOOM using the following Meeting ID: 871-3245-3418. The meeting will also be streamed live to the ‘Bognor Regis Town Council’ Facebook page. DATED this 12th day of JANUARY 2021 TOWN CLERK AGENDA AND BUSINESS 1. Welcome by Chairman and Apologies for Absence 2. Declarations of Interest Members and Officers are invited to make any declarations of Disclosable Pecuniary and/or Ordinary Interests that they may have in relation to items on this agenda and are reminded that they should re- declare their Interest before consideration of the item or as soon as the Interest becomes apparent and if not previously included on their Register of Interests to notify the Monitoring Officer within 28 days. -

West Sussex County Council

PRINCIPAL LOCAL BUS SERVICES BUS OPERATORS RAIL SERVICES GettingGetting AroundAround A.M.K. Coaches, Mill Lane, Passfield, Liphook, Hants, GU30 7RP AK Eurostar Showing route number, operator and basic frequency. For explanation of operator code see list of operators. Telephone: Liphook (01428) 751675 WestWest SussexSussex Website: www.AMKXL.com Telephone: 08432 186186 Some school and other special services are not shown. A Sunday service is normally provided on Public Holidays. Website: www.eurostar.co.uk AR ARRIVA Serving Surrey & West Sussex, Friary Bus Station, Guildford, by Public Transport Surrey, GU1 4YP First Capital Connect by Public Transport APPROXIMATE APPROXIMATE Telephone: 0844 800 4411 Telephone: 0845 026 4700 SERVICE FREQUENCY INTERVALS SERVICE FREQUENCY INTERVALS Website: www.arrivabus.co.uk ROUTE DESCRIPTION OPERATOR ROUTE DESCRIPTION OPERATOR Website: www.firstcapitalconnect.co.uk NO. NO. AS Amberley and Slindon Village Bus Committee, Pump Cottage, MON - SAT EVENING SUNDAY MON - SAT EVENING SUNDAY Church Hill, Slindon, Arundel, West Sussex BN18 0RB First Great Western Telephone: Slindon (01243) 814446 Telephone: 08457 000125 Star 1 Elmer-Bognor Regis-South Bersted SD 20 mins - - 100 Crawley-Horley-Redhill MB 20 mins hourly hourly Website: www.firstgreatwestern.co.uk Map & Guide BH Brighton and Hove, Conway Street, Hove, East Sussex BN3 3LT 1 Worthing-Findon SD 30 mins - - 100 Horsham-Billingshurst-Pulborough-Henfield-Burgess Hill CP hourly - - Telephone: Brighton (01273) 886200 Gatwick Express Website: www.buses.co.uk -

E-News September 2015

No 10 September 2015 Peacehaven Town Council Volunteers are needed to pedal power the open-air cinema The film’s on — get pedalling! Cycle-powered outdoor cinema is coming to Centenary Park on Saturday, September 19. Pedal furiously on special bikes while you enjoy the action-packed 1969 classic The Italian Job. Doors open at 7pm. It’s free but booking is essential at www.bigparksproject.org.uk or call 01273 471600. Have your say on By bike over the Rumble with ring homes — Page 2 Downs — Page 3 kings — Page 4 Making Peacehaven a better place to live,work and visit www.peacehavencouncil.co.uk 1 Tel: 01273 585493 Peacehaven Town Council Have a say on homes Council The town council is reminding residents officers and architects. The district meetings it is important they have a say on plans council says affordable housing is at the The public may attend any to build homes in Peacehaven. The next heart of its vision to build about 415 council or committee community consultation on Lewes homes across the whole of the district. meeting. Each meeting is District Council’s proposals for the Seven sites across Peacehaven have normally held at Community homes will be held at the Meridian been listed as possible land for building House in the Meridian Centre on Monday, November 2, flats and houses. Controversially, some Centre and starts at 7.30pm between 4.30pm and 7.30pm. of them are car parks off the South unless stated. It will be a drop-in surgery for Coast Road. -

Local Development Division Planning Applications

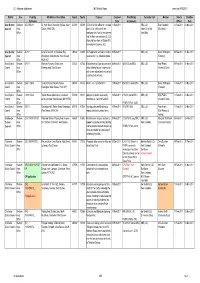

LD - Allocated Applications MIS Weekly Report week start 07/02/2011 District Area Planning Site Address Description Xpoint Ypoint Proposal Received Prev.History Consultee / LO Member Date to Deadline Reference Date & Comments Officer Date Adur District Southern ADC/0052/11 70, High Street, Shoreham-by-Sea, West 521391 105066 COU of 1st floor offices to 1 x 2-bed 11-Feb-2011 - SRU (LO) Brian Coomber 11-Feb-2011 04-Mar-2011 Council Area Sussex, BN43 5DB flat (C3 1-4) with room in the Adam Ch (s106) (Shoreham) Office roofspace (incl. front & rear dormers John Mills and 1st floor rear extension) & COU of ground floor from Art Studio (A1) to employment agency (A2). Arun District Western AL/7/11 Land To Rear Of, 31, Meadow Way, 493842 104835 OUT application with some matters 08-Feb-2011 - SRU (LO) Derek Whittington 09-Feb-2011 01-Mar-2011 Council Area Westergate, Aldingbourne, West Sussex, reserved for 1 no. 2 bed bungalow. (Fontwell) Office PO20 3QT Arun District Western W/1/11 Yeomans Nursery, Sefton Lane, 503122 107322 Replacement of 2 glasshouses with 08-Feb-2011 W/5/10 (Liam/SRU) SRU (LO) Nigel Peters 09-Feb-2011 01-Mar-2011 Council Area Warningcamp, West Sussex office building for use in connection (Arundel & Wick) Office with current educational units on site & horticultural activities. Arun District Western EG/2/11/DOC Hunters Chase, Fontwell Avenue, 494806 106314 DOC 3, 4 & 12 of EG/15/10. 10-Feb-2011 EG/15/10 (Jamie/SRU) SRU (LO) Derek Whittington 11-Feb-2011 03-Mar-2011 Council Area Eastergate, West Sussex, PO20 3RY (Fontwell) Office Arun District Western LY/3/11/DOC Thelton House Apartments, Crossbush 503309 106011 Approval of details reserved by 10-Feb-2011 LY/2/10 (Jamie/SRU) SRU (LO) Nigel Peters 11-Feb-2011 03-Mar-2011 Council Area Lane, Lyminster, West Sussex, BN18 9PQ conditions 2, 3 and 4 of LY/2/10. -

MINUTES of the PLANNING COMMITTEE Held Virtually on Monday 9 November 2020

MINUTES of the PLANNING COMMITTEE held virtually on Monday 9 November 2020 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Present: Janice Henwood Chairman Graham Allen Andrew Barrett-Miles Tofojjul Hussain Max Nielsen Kathleen Willis* Also Present: Peter Chapman Matthew Cornish Robert Duggan Robert Eggleston Anne Eves Lee Gibbs Sylvia Neumann * Denotes non-attendance. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- (19.00) 233. OPEN FORUM A member of the public addressed the Committee on DM/20/3953. They commented that at the last planning meeting the Council had recommended refusal on an application to fell three oaks. DM/20/3953 was another example where the resident would like to see the Council question the reasoning for felling an oak tree. The oak trees were an amenity and a community asset, and contributed to the character of the community. The resident understood that the tree was potentially causing issues to a property, but it should be a last resort to fell the tree. A second member of the public spoke on DM/20/3953. The tree was on their property. The member of the public had recently spoken to Councillor Anne Eves, this was the first they had heard there was an issue with the tree. They understood that the neighbour was having issues with subsidence on their conservatory, and previously an ash tree on the industrial estate behind the properties had been felled to try and resolve this. The tree was an amenity on the property, and blocked an unattractive view of the neighbouring industrial estate. The resident had been looking at alternatives, and there was a suggestion that trimming the tree could help with the issue. -

Hill House, Keymer Road, Burgess Hill, West Sussex RH15 0AH

Hill House, Keymer Road, Burgess Hill, West Sussex RH15 0AH An extended and well presented 5 bedroom family home on the popular southern side of the town, within easy reach of the mainline railway station. About a third of an acre. 5 bedroom family home Popular southern side of town Easy access to railway station Heated swimming pool About a third of an acre Guide price £850,000 Freehold Savills Haywards Heath 37-39 Perrymount Road, Haywards Heath, West Sussex, RH16 3BN Caroline Slocombe [email protected] +44 (0) 1444 446 000 Savills - World leading property services. In excess of 200 offices worldwide, over 80 in the UK. savills.co.uk Page 1 of 5 Hill House, Keymer Road, Burgess Hill, West Sussex RH15 0AH Savills Haywards Heath Caroline Slocombe +44 (0) 1444 446 000 [email protected] savills.co.uk Page 2 of 5 Hill House, Keymer Road, Burgess Hill, West Sussex RH15 0AH Situation the house to the rear garden, and to the north an enclosed paved Hill House is situated on the popular southern side of Burgess Hill area giving access to the attached single garage. and is ideally located for the town centre, schools (in particular, Burgess Hill School for Girls) and mainline railway station. Adjoining the rear of the house is a raised, paved terrace and Local Amenities: Burgess Hill has a good range of local amenities outdoor entertaining area, edged by wooden railings and with a including a variety of restaurants, wine bars, shops and productive grape vine and steps leading down to the lawn. -

Crouchers Farm Streat, East Sussex Crouchers Farm, Streat Lane Streat, East Sussex Bn6 8Rt

CROUCHERS FARM STREAT, EAST SUSSEX CROUCHERS FARM, STREAT LANE STREAT, EAST SUSSEX BN6 8RT Substantial Grade II listed detached house in a lovely rural location w Entrance hall w reception hall w sitting room w dining room w study w kitchen/breakfast room w utility room w boiler room w master bedroom with bathroom and dressing room w 5 further bedrooms (2 en suite) w shower room w triple bay garage and office w field shelter w car port w store/kennel w gardens & paddock w about 2.44 acres Description Set in a delightful rural location in the South Downs National Park, Crouchers Farm is a charming Grade II listed farmhouse believed to date from the eighteenth century or earlier, and subsequently extended in the late twentieth century. Today, the property offers well-presented and substantial accommodation extending in all to 3,779 sq ft. The property has charming red brick and tile hung elevations under a tiled roof, a central open porch and painted wood front door opening to the entrance hall. The formal dining room has an impressive inglenook fireplace, with cast iron hood and fire basket; also in the older portion of the house is the breakfast room, which is opens to the vaulted farmhouse style kitchen with wood burning stove, solid wood counters, a Rangemaster oven and a breakfast bar. The kitchen is open to the reception hall, a wonderful vaulted room with a large roof light, forming the link between the original house and the single-storey extension built on the footprint of the old dairy buildings.