Vincent Massey 1926–2002

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Insight from the Sociology of Science

CHAPTER 7 INSIGHT FROM THE SOCIOLOGY OF SCIENCE Science is What Scientists Do It has been argued a number of times in previous chapters that empirical adequacy is insufficient, in itself, to establish the validity of a theory: consistency with the observable ‘facts’ does not mean that a theory is true,1 only that it might be true, along with other theories that may also correspond with the observational data. Moreover, empirical inadequacy (theories unable to account for all the ‘facts’ in their domain) is frequently ignored by individual scientists in their fight to establish a new theory or retain an existing one. It has also been argued that because experi- ments are conceived and conducted within a particular theoretical, procedural and instrumental framework, they cannot furnish the theory-free data needed to make empirically-based judgements about the superiority of one theory over another. What counts as relevant evidence is, in part, determined by the theoretical framework the evidence is intended to test. It follows that the rationality of science is rather different from the account we usually provide for students in school. Experiment and observation are not as decisive as we claim. Additional factors that may play a part in theory acceptance include the following: intuition, aesthetic considerations, similarity and consistency among theories, intellectual fashion, social and economic influences, status of the proposer(s), personal motives and opportunism. Although the evidence may be inconclusive, scientists’ intuitive feelings about the plausibility or aptness of particular ideas will make it appear convincing. The history of science includes many accounts of scientists ‘sticking to their guns’ concerning a well-loved theory in the teeth of evidence to the contrary, and some- times in the absence of any evidence at all. -

The Joys and Burdens of Our Heroes 12/05/2021

More Fun Than Fun: The Joys and Burdens of Our Heroes 12/05/2021 An iconic photo of Konrad Lorenz with his favourite geese. Photo: Willamette Biology, CC BY-SA 2.0 This article is part of the ‘More Fun Than Fun‘ column by Prof Raghavendra Gadagkar. He will explore interesting research papers or books and, while placing them in context, make them accessible to a wide readership. RAGHAVENDRA GADAGKAR Among the books I read as a teenager, two completely changed my life. One was The Double Helix by Nobel laureate James D. Watson. This book was inspiring at many levels and instantly got me addicted to molecular biology. The other was King Solomon’s Ring by Konrad Lorenz, soon to be a Nobel laureate. The study of animal behaviour so charmingly and unforgettably described by Lorenz kindled in me an eternal love for the subject. The circumstances in which I read these two books are etched in my mind and may have partly contributed to my enthusiasm for them and their subjects. The Double Helix was first published in London in 1968 when I was a pre-university student (equivalent to 11th grade) at St Joseph’s college in Bangalore and was planning to apply for the prestigious National Science Talent Search Scholarship. By then, I had heard of the discovery of the double-helical structure of DNA and its profound implications. I was also tickled that this momentous discovery was made in 1953, the year of my birth. I saw the announcement of Watson’s book on the notice board in the British Council Library, one of my frequent haunts. -

Discovery of DNA Structure and Function: Watson and Crick By: Leslie A

01/08/2018 Discovery of DNA Double Helix: Watson and Crick | Learn Science at Scitable NUCLEIC ACID STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION | Lead Editor: Bob Moss Discovery of DNA Structure and Function: Watson and Crick By: Leslie A. Pray, Ph.D. © 2008 Nature Education Citation: Pray, L. (2008) Discovery of DNA structure and function: Watson and Crick. Nature Education 1(1):100 The landmark ideas of Watson and Crick relied heavily on the work of other scientists. What did the duo actually discover? Aa Aa Aa Many people believe that American biologist James Watson and English physicist Francis Crick discovered DNA in the 1950s. In reality, this is not the case. Rather, DNA was first identified in the late 1860s by Swiss chemist Friedrich Miescher. Then, in the decades following Miescher's discovery, other scientists--notably, Phoebus Levene and Erwin Chargaff--carried out a series of research efforts that revealed additional details about the DNA molecule, including its primary chemical components and the ways in which they joined with one another. Without the scientific foundation provided by these pioneers, Watson and Crick may never have reached their groundbreaking conclusion of 1953: that the DNA molecule exists in the form of a three-dimensional double helix. The First Piece of the Puzzle: Miescher Discovers DNA Although few people realize it, 1869 was a landmark year in genetic research, because it was the year in which Swiss physiological chemist Friedrich Miescher first identified what he called "nuclein" inside the nuclei of human white blood cells. (The term "nuclein" was later changed to "nucleic acid" and eventually to "deoxyribonucleic acid," or "DNA.") Miescher's plan was to isolate and characterize not the nuclein (which nobody at that time realized existed) but instead the protein components of leukocytes (white blood cells). -

Cambridge's 92 Nobel Prize Winners Part 2 - 1951 to 1974: from Crick and Watson to Dorothy Hodgkin

Cambridge's 92 Nobel Prize winners part 2 - 1951 to 1974: from Crick and Watson to Dorothy Hodgkin By Cambridge News | Posted: January 18, 2016 By Adam Care The News has been rounding up all of Cambridge's 92 Nobel Laureates, celebrating over 100 years of scientific and social innovation. ADVERTISING In this installment we move from 1951 to 1974, a period which saw a host of dramatic breakthroughs, in biology, atomic science, the discovery of pulsars and theories of global trade. It's also a period which saw The Eagle pub come to national prominence and the appearance of the first female name in Cambridge University's long Nobel history. The Gender Pay Gap Sale! Shop Online to get 13.9% off From 8 - 11 March, get 13.9% off 1,000s of items, it highlights the pay gap between men & women in the UK. Shop the Gender Pay Gap Sale – now. Promoted by Oxfam 1. 1951 Ernest Walton, Trinity College: Nobel Prize in Physics, for using accelerated particles to study atomic nuclei 2. 1951 John Cockcroft, St John's / Churchill Colleges: Nobel Prize in Physics, for using accelerated particles to study atomic nuclei Walton and Cockcroft shared the 1951 physics prize after they famously 'split the atom' in Cambridge 1932, ushering in the nuclear age with their particle accelerator, the Cockcroft-Walton generator. In later years Walton returned to his native Ireland, as a fellow of Trinity College Dublin, while in 1951 Cockcroft became the first master of Churchill College, where he died 16 years later. 3. 1952 Archer Martin, Peterhouse: Nobel Prize in Chemistry, for developing partition chromatography 4. -

Independent Discovery in Biology: Investigating Styles of Scientific Research

Medical History, 1993, 37: 432-441. INDEPENDENT DISCOVERY IN BIOLOGY: INVESTIGATING STYLES OF SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH by NICHOLAS RUSSELL * INTRODUCTION The fact that discoveries are often made independently is a commonplace of the history and sociology of science. Analysis of independent discovery has potential for evaluating the relative importance of social and individual components in the conduct of scientific research.' For instance, in a classic paper, Barber and Fox2 discussed the independent discovery of a bizarre phenomenon by two scientists. Aaron Kellner and Lewis Thomas both found that injections of the enzyme papain caused the upright ears of rabbits to droop over their heads like spaniels'. At first neither could find an explanation for it. Both abandoned the search and Kellner never returned to it, even though he went on to use the floppy ear response as a technical assay for measuring the potency of papain samples. Lewis Thomas did look into it again and discovered that papain completely altered the structure of the matrix of cartilage, not only in the ears but everywhere else in the animal as well. Both Thomas and Kellner had originally missed these changes because they had assumed that cartilage was a stable and uninteresting tissue. Barber and Fox concluded that Thomas persisted with the problem because it played a role in his developing research while the floppy-eared phenomenon was irrelevant to Kellner's interests. Barber and Fox hinted that more personal factors were involved as well, a theme expanded by Thomas in a later autobiographical essay.3 Thomas had found the collapsed ears amusing. -

Introduction and Historical Perspective

Chapter 1 Introduction and Historical Perspective “ Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution. ” modified by the developmental history of the organism, Theodosius Dobzhansky its physiology – from cellular to systems levels – and by the social and physical environment. Finally, behaviors are shaped through evolutionary forces of natural selection OVERVIEW that optimize survival and reproduction ( Figure 1.1 ). Truly, the study of behavior provides us with a window through Behavioral genetics aims to understand the genetic which we can view much of biology. mechanisms that enable the nervous system to direct Understanding behaviors requires a multidisciplinary appropriate interactions between organisms and their perspective, with regulation of gene expression at its core. social and physical environments. Early scientific The emerging field of behavioral genetics is still taking explorations of animal behavior defined the fields shape and its boundaries are still being defined. Behavioral of experimental psychology and classical ethology. genetics has evolved through the merger of experimental Behavioral genetics has emerged as an interdisciplin- psychology and classical ethology with evolutionary biol- ary science at the interface of experimental psychology, ogy and genetics, and also incorporates aspects of neuro- classical ethology, genetics, and neuroscience. This science ( Figure 1.2 ). To gain a perspective on the current chapter provides a brief overview of the emergence of definition of this field, it is helpful -

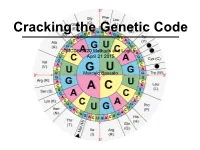

MCDB 5220 Methods and Logics April 21 2015 Marcelo Bassalo

Cracking the Genetic Code MCDB 5220 Methods and Logics April 21 2015 Marcelo Bassalo The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) Frederick Griffith The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) Oswald Avery Alfred Hershey Martha Chase The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) Linus Carl Pauling The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) • The structure of DNA (1953) James Watson and Francis Crick The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) • The structure of DNA (1953) How is DNA (4 nucleotides) the genetic material while proteins (20 amino acids) are the building blocks? ? DNA Protein ? The Coding Craze ? DNA Protein What was already known? • DNA resides inside the nucleus - DNA is not the carrier • Protein synthesis occur in the cytoplasm through ribosomes {• Only RNA is associated with ribosomes (no DNA) - rRNA is not the carrier { • Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) was a homogeneous population The “messenger RNA” hypothesis François Jacob Jacques Monod The Coding Craze ? DNA RNA Protein RNA Tie Club Table from Wikipedia The Coding Craze Who won the race Marshall Nirenberg J. -

In 1953 in England James Watson and Francis Crick Discovered the Structure of DNA in the Now-Famous Scientific Narrative Known As the “Race Towards the Double Helix”

THE NARRATIVES OF SCIENCE: LITERARY THEORY AND DISCOVERY IN MOLECULAR BIOLOGY PRIYA VENKATESAN In 1953 in England James Watson and Francis Crick discovered the structure of DNA in the now-famous scientific narrative known as the “race towards the double helix”. Meanwhile in France, Roland Barthes published his first book, Writing Degree Zero, on literary theory, which became the intellectual precursor for the new human sciences that were developing based on Saussurean linguistics. The discovery by Watson and Crick of the double helix marked a definitive turning point in the development of the life sciences, paving the way for the articulation of the genetic code and the emergence of molecular biology. The publication by Barthes was no less significant, since it served as an exemplar for elucidating how literary narratives are structured and for formulating how textual material is constructed. As Françoise Dosse notes, Writing Degree Zero “received unanimous acclaim and quickly became a symptom of new literary demands, a break with tradition”.1 Both the work of Roland Barthes and Watson and Crick served as paradigms in their respective fields. Semiotics, the field of textual analysis as developed by Barthes in Writing Degree Zero, offered a new direction in the structuring of narrative whereby each distinct unit in a story formed a “code” or “isotopy” that categorizes the formal elements of the story. The historical concurrence of the discovery of the double helix and the publication of Writing Degree Zero may be mere coincidence, but this essay is an exploration of the intellectual influence that both events may have had on each other, since both the discovery of the double helix and Barthes’ publication gave expression to the new forms of knowledge 1 Françoise Dosse, History of Structuralism: The Rising Sign, 1945-1966, trans. -

The Story of César Milstein and Monoclonal Antibodies: Introduction Page 1 of 4

The Story of César Milstein and Monoclonal Antibodies: Introduction Page 1 of 4 Custom Search Search A HEALTHCARE REVOLUTION IN THE MAKING The Story of César Milstein and Monoclonal Antibodies Collated and written by Dr Lara Marks Today six out of ten of the best selling drugs in the world are monoclonal antibody therapeutics. One of these, Humira®, which is a treatment for rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune conditions, was listed as the top selling drug across the globe in 2012 with a revenue of US$9.3 billion. Based on its current performance many predict the annual sales of the drug will surpass the peak sales of Lipitor, a treatment for lowering cholesterol, that is the best selling therapeutic of all time. Currently monoclonal antibody drugs make up a third of all new medicines introduced worldwide. http://www.whatisbiotechnology.org/exhibitions/milstein 4/13/2017 PFIZER EX. 1524 Page 1 The Story of César Milstein and Monoclonal Antibodies: Introduction Page 2 of 4 Portrait of César Milstein. Photo credit: Godfrey Argent Studio Monoclonal antibodies are not only successful drugs, but are powerful tools for a wide range of medical applications. On the research front they are essential probes for determining the pathological pathway and cause of diseases like cancer and autoimmune and neurological disorders. They are also used for typing blood and tissue, a process that is vital to blood transfusion and organ transplants. In addition, monoclonal antibodies are critical components in diagnostics, having increased the speed and accuracy of tests. Today the antibodies are used for the detection of multiple conditions, ranging from pregnancy and heart attacks, to pandemic flu, AIDS and diseases like anthrax and smallpox released by biological weapons. -

15/5/40 Liberal Arts and Sciences Chemistry Irwin C. Gunsalus Papers, 1877-1993 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Irwin C

15/5/40 Liberal Arts and Sciences Chemistry Irwin C. Gunsalus Papers, 1877-1993 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Irwin C. Gunsalus 1912 Born in South Dakota, son of Irwin Clyde and Anna Shea Gunsalus 1935 B.S. in Bacteriology, Cornell University 1937 M.S. in Bacteriology, Cornell University 1940 Ph.D. in Bacteriology, Cornell University 1940-44 Assistant Professor of Bacteriology, Cornell University 1944-46 Associate Professor of Bacteriology, Cornell University 1946-47 Professor of Bacteriology, Cornell University 1947-50 Professor of Bacteriology, Indiana University 1949 John Simon Guggenheim Fellow 1950-55 Professor of Microbiology, University of Illinois 1955-82 Professor of Biochemistry, University of Illinois 1955-66 Head of Division of Biochemistry, University of Illinois 1959 John Simon Guggenheim Fellow 1959-60 Research sabbatical, Institut Edmund de Rothchild, Paris 1962 Patent granted for lipoic acid 1965- Member of National Academy of Sciences 1968 John Simon Guggenheim Fellow 1972-76 Member Levis Faculty Center Board of Directors 1977-78 Research sabbatical, Institut Edmund de Rothchild, Paris 1973-75 President of Levis Faculty Center Board of Directors 1978-81 Chairman of National Academy of Sciences, Section of Biochemistry 1982- Professor of Biochemistry, Emeritus, University of Illinois 1984 Honorary Doctorate, Indiana University 15/5/40 2 Box Contents List Box Contents Box Number Biographical and Personal Biographical Materials, 1967-1995 1 Personal Finances, 1961-65 1-2 Publications, Studies and Reports Journals and Reports, 1955-68 -

Eulogy Professor Emeritus Brigitte A. Askonas You Have Doubtless Often

Eulogy Professor Emeritus Brigitte A. Askonas You have doubtless often heard it said that such a person needs no introduction. Well, I reckon the recipient of the 2007 Robert Koch Gold Medal deserves an introduction. I would like to introduce her, as she is not someone to blow her own trumpet. She would never describe herself as the grand dame of cellular immunology. She would never talk about the great influence she has had on immunology. She would never say that she has mentored countless outstanding scientists. She would never proudly list all her honorary memberships of scientific societies and academies and all her honorary professorships at top universities. Professor Brigitte Askonas is not very forthcoming about her successes, which is precisely why an introduction is necessary. We would like her to know how much we value her contributions to science and how impressed we are by the formative influence she has had on the biosciences in Europe and in particular on immunology. Ita Askonas started her scientific career as a biochemist. In 1944, she was awarded a bachelor’s degree in biochemistry from McGill University in Montreal, Canada. In 1952, she received her PhD from the Biochemistry Department of the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom, where she served her scientific apprenticeship under Malcolm Dixon. She studied muscle enzymes, by no means the worst grounding for her subsequent research. After completing her doctorate, she became a member of the Scientific Staff at the National Institute of Medical Research in Mill Hill, London. There, she first continued with her enzyme studies and biochemical research. -

NATURE July 12, 1947 Vol

44 NATURE July 12, 1947 Vol. 160 The energy, enterprise and judgment he displayed build up the new Russia on sound and progressive during the difficult war years would be considered lines. exceptional, even in one trained to important Stalin succeeded Lenin and, under his leadership, administrative tasks. That they should be found in the Soviet Government gradually assumed its present a man of science brought up in academic seclusion form. The State Political Administration, afterwards and long confined to the narrow paths of fundamental the G.P.U., was created in 1922, and rapidly grew to scientific research may be thought a portent. be a powerful instrument of Government policy. On this subject, the memoirs are singularly Ipatieff's position became increasingly dangerous. revealing and present an interesting psychological His refusal to join the Party, his outspoken. criticism study. Perhaps the main characteristics of the author of his political colleagues and his frequent visits may be summarized as an abiding enthusiasm for abroad served to arouse the suspicion of the G.P.U. scientjfic studies, a deep sincerity of purpose and Many of his contemporaries were arrested and abounding self-confidence. From that day in early imprisoned or executed. "I reckoned," he says, youth when, with some trepidation, he waited upon "that up to 1930, of all the military engineer-techno the great chemist Mendeleeff and received from the logists who had completed their training at the lips of the sage an opinion that his knowledge was Artillery Academy, only two or three were left in too meagre for experimental work, until the occasion Soviet territory.