Joint Parallel Report to the United Nations Human

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DAO Level 3 Certificate in Military Engineering (Armoured) Titan and Trojan Crew Supervision

Qualification Handbook DAO Level 3 Certificate in Military Engineering (Armoured) Titan and Trojan crew supervision QN: 603/3232/3 The Qualification Overall Objective for the Qualifications This handbook relates to the following qualification: DAO Level 3 Certificate in Military Engineering (Armoured) Titan and Trojan crew supervision Pre-entry Requirements Learners are required to have completed the Class ME (Armd) Class 0-2 course, must be fully qualified AFV crewman and hold full category H driving licence Unit Content and Rules of Combination This qualification is made up of a total of 6 mandatory units and no optional units. To be awarded this qualification the candidate must achieve a total of 13 credits as shown in the table below. Unit Unit of assessment Level GLH TQT Credit number value L/617/0309 Supervise Titan Operation and 3 25 30 3 associated Equipment L/617/0312 Supervise Titan Crew 3 16 19 2 R/617/0313 Supervise Trojan Operation and 3 26 30 3 associated Equipment D/617/0315 Supervise Trojan Crew 3 16 19 2 H/617/0316 Supervise Trojan and Titan AFV 3 10 19 2 maintenance tasks K/617/0317 Carry out emergency procedures and 3 7 11 1 communication for Trojan and Titan AFV Totals 100 128 13 Age Restriction This qualification is available to learners aged 18 years and over. Opportunities for Progression This qualification creates a number of opportunities for progression through career development and promotion. Exemption No exemptions have been identified. 2 Credit Transfer Credits from identical RQF units that have already been achieved by the learner may be transferred. -

Palestine and the Struggle for Global Justice

Studies in Social Justice Volume 4, Issue 2, 199-215, 2010 Between Acceleration and Occupation: Palestine and the Struggle for Global Justice JOHN COLLINS Department of Global Studies, St. Lawrence University ABSTRACT This article explores the contemporary politics of global violence through an examination of the particular challenges and possibilities facing Palestinians who seek to defend their communities against an ongoing settler-colonial project (Zionism) that is approaching a crisis point. As the colonial dynamic in Israel/Palestine returns to its most elemental level—land, trees, homes—it also continues to be a laboratory for new forms of accelerated violence whose global impact is hard to overestimate. In such a context, Palestinians and international solidarity activists find themselves confronting a quintessential 21st-century activist dilemma: how to craft a strategy of what Paul Virilio calls “popular defense” at a time when everyone seems to be implicated in the machinery of global violence? I argue that while this dilemma represents a formidable challenge for Palestinians, it also helps explain why the Palestinian struggle is increasingly able to build bridges with wider struggles for global justice, ecological sustainability, and indigenous rights. Much like the ubiquitous and misleading phrase “Israeli-Palestinian conflict,” the conventional usage of the term “occupation” to describe Israel’s post-1967 control of the West Bank and Gaza serves to deflect attention from the settler-colonial structures that continue to shape the contours of social reality at all levels in Israel/Palestine.1 The dominant discourse of “occupation” is built on an unstated assumption that it is the presence of soldiers, whether that presence is viewed as oppressive or defensive, that makes the territories “occupied.” In fact, contemporary Palestine is the site of not one, but two occupations, both of which are occluded by this assumption. -

West Bank and Gaza 2020 Human Rights Report

WEST BANK AND GAZA 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Palestinian Authority basic law provides for an elected president and legislative council. There have been no national elections in the West Bank and Gaza since 2006. President Mahmoud Abbas has remained in office despite the expiration of his four-year term in 2009. The Palestinian Legislative Council has not functioned since 2007, and in 2018 the Palestinian Authority dissolved the Constitutional Court. In September 2019 and again in September, President Abbas called for the Palestinian Authority to organize elections for the Palestinian Legislative Council within six months, but elections had not taken place as of the end of the year. The Palestinian Authority head of government is Prime Minister Mohammad Shtayyeh. President Abbas is also chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization and general commander of the Fatah movement. Six Palestinian Authority security forces agencies operate in parts of the West Bank. Several are under Palestinian Authority Ministry of Interior operational control and follow the prime minister’s guidance. The Palestinian Civil Police have primary responsibility for civil and community policing. The National Security Force conducts gendarmerie-style security operations in circumstances that exceed the capabilities of the civil police. The Military Intelligence Agency handles intelligence and criminal matters involving Palestinian Authority security forces personnel, including accusations of abuse and corruption. The General Intelligence Service is responsible for external intelligence gathering and operations. The Preventive Security Organization is responsible for internal intelligence gathering and investigations related to internal security cases, including political dissent. The Presidential Guard protects facilities and provides dignitary protection. -

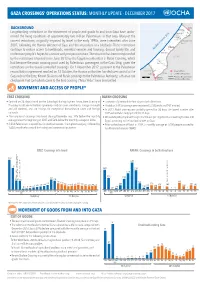

Gaza Crossings' Operations Status: Monthly

GAZA CROSSINGS’ OPERATIONS STATUS: MONTHLY UPDATE - DECEMBER 2017 BACKGROUND Erez Beit Lahiya ¹ ! Longstanding restrictions on the movement of people and goods to and from Gaza have under- ! Jabalya ! Beit Hanoun mined the living conditions of approximately two million Palestinians in that area. Many of the Gaza City ! n Sea ! Ash Shuja’iyeh current restrictions, originally imposed by Israel in the early 1990s, were intensified after June anea Nahal Oz Karni 2007, following the Hamas takeover of Gaza and the imposition of a blockade. These restrictions iterr GAZA Med 21 continue to reduce access to livelihoods, essential services and housing, disrupt family life, and 30! 0 undermine people’s hopes for a secure and prosperous future. The situation has been compounded Deir al B alah by the restrictions imposed since June 2013 by the Egyptian authorities at Rafah Crossing, which ISRAEL ! had become the main crossing point used by Palestinian passengers in the Gaza Strip, given the Khan Yunis Khuza’a ! restrictions on the Israeli-controlled crossings. On 1 November 2017, pursuant to the Palestinian 14389 Rafah EGYPT ! Crossing Point reconciliation agreement reached on 12 October, the Hamas authorities handed over control of the Sufa Rafah¹º» Closed Crossing Point Armistice Declaration Line Gaza side of the Erez, Kerem Shalom and Rafah crossings to the Palestinian Authority; a Hamas-run 5 Km ¹º» Kerem checkpoint that controlled access to the Erez crossing (“Arba’ Arba’”) was dismantled. Shalom International Boundary MOVEMENT AND ACCESS OF PEOPLE* EREZ CROSSING RAFAH CROSSING • Opened on 26 days (closed on five Saturdays) during daytime hours, from Sunday to • Exceptionally opened for four days in both directions. -

Litigating Corporate Complicity in Israeli Violations of International Law in the U.S

97 Corrie et al v. Caterpillar: Litigating Corporate Complicity in Israeli Violations of International Law in the U.S. Courts Grietje Baars* 1 INTRODUCTION1 In 2005 an attempt was made at enforcing international law against an American corporation said to be complicit in war crimes, extrajudicial killing and cruel, inhumane and degrading treatment committed by the Israeli military. The civil suit, brought in a U.S. court, was dismissed without a hearing, in a brief statement mainly citing reasons of political expedience. The claimants in Corrie et al v. Caterpillar2 include relatives of several Palestinians, and American peace activist Rachel Corrie, who were killed or injured in the process of house demolitions carried out using Caterpillar’s D9 and D10 bulldozers. They brought a civil suit in a U.S. court under the Alien Tort Claims Act,3 for breaches of international law, seeking compensatory damages and an order to enjoin Caterpillar’s sale of bulldozers to Israel until its military stops its practice of house demolitions. An appeal is pending and will be decided on in the latter half of 2006. * PhD Candidate, University College London and Coordinator, International Criminal Law at the Institute of Law, Birzeit University. 1 The author thanks Victor Kattan, Jason Beckett, Jörg Kammerhofer, Akbar Rasulov, André de Hoogh, Anne Massagee, Reem Al-Botmeh and Munir Nuseibah for their helpful comments and suggestions, and Maria LaHood of the Center for Constitutional Rights in New York for providing the documentation. Any mistakes are the author’s own. This article is an elaboration of a paper presented at the conference, “The Question of Palestine in International Law” at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London, on 23-24 November 2005. -

NSIAD-88-77 Army Disposal

United States General Accounting Office Report to the Chairman, Subcommittee on GAO>; Oversight and Investigations, Committee on Energy and Commerce, House of Representatives September 1988 ARMYDISPOSAL Construction Equipment Prematurely Disposed of in Europe RESTRKTED-Not to be released outside the Gend Accounting Office except on the basis of the specifk 8~4 by the Of&e of CongressionalRelations. United States General Accounting Office GAO Washington, D.C. 20548 National Security and International Affairs Division B-229358 September 20,1988 The Honorable John Dingell Chairman, Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations Committee on Energy and Commerce House of Representatives Dear Mr. Chairman: The Army, having decided that its fleet of construction vehicles was becoming too costly to keep in repair, directed European units in 1985 to dispose of commercially available combat engineer construction vehi- cles. The Army purchased 850 replacement vehicles for Europe costing about $79 million. The purchase was part of a worldwide replacement program totaling about $470 million through fiscal year 1987. As you requested, we reviewed the Army’s replacement of construction vehicles in Europe. Our objective was to determine the basis for replac- ing these vehicles. We agree with the Army’s goal to replace worn-out vehicles with stan- dardized ones, but question its decision to dispose of usable vehicles without showing that it was cost-effective to do so. Army officials stated that old construction vehicles were difficult to support and that high repair costs made replacing the entire fleet -regardless of condi- tion-cost-effective. We found no analyses to support the Army’s position. -

Simplify the of Rear Wheel Arch Panel for the Caterpillar 980H Medium Wheel Loader

Simplify the of Rear Wheel Arch Panel for the Caterpillar 980H Medium Wheel Loader A Major Qualifying Project submitted to the faculty of Worcester Polytechnic Institute in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of the Bachelor of Science. Submitted By: Peter Wallace Brendan McLaughlin In partnership with Shanghai University and Partners: Weiqing Chu Mengyuan Guo Chao Xie Sponsoring Agency: Caterpillar Inc. Advisors: Kevin Rong Xiuling Huang Amy Zeng Shuai Guo AUTHORSHIP ABSTRACT…………………………………………………………………….Brendan INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………….Peter BACKGROUND……………………………………………………………..….Brendan EXECUTIVE SUMMARY……………………………………………………….…Peter OBJECTIVE………………………………………………………………..Peter/Brendan METHODOLOGY……………………………………………………………..……Peter RESULTS…………………………………………………………………………..Brendan RECOMMENDATIONS/CONCLUSIONS……………………………..…Peter/Brendan 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Our group would like to thank the following individuals for their help and support throughout this project: Scott Panse, Engineer at Caterpillar Professor Xiuling Huang, Shanghai University Kevin Rong, Worcester Polytechnic Institute Amy Zeng, Worcester Polytechnic Institute 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Authorship ........................................................................................................................ 1 Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... 2 List of figures ................................................................................................................... -

Beneficiary and Community Perspectives on the Palestinian National Cash Transfer Programme

TRANSFORMING COUNTRY BRIEFING CASH TRANSFERS Beneficiary and community perspectives on the Palestinian National Cash Transfer Programme transformingcashtransfers.org Introduction transformingcashtransfers.org Our research aimed to explore the perceptions of cash transfer programme beneficiaries and implementers and other community members, in order to ensure their views are better reflected in policy and programming. Introduction transformingcashtransfers.org There is growing evidence internationally of positive links Key points: between social protection and poverty and vulnerability reduction. However, there has been limited recognition of the • De-developmental policies, recurring social inequalities that perpetuate poverty, such as gender insecurity and dependency on donor inequality, unequal citizenship status and displacement funding are among the key challenges through conflict, and the role social protection can play in in advancing social protection in the tackling these interlinked socio-political vulnerabilities. Occupied Palestinian Territories. • The Palestinian National Cash Transfer This country briefing synthesises qualitative research focusing Programme is an important but on beneficiary and community perceptions of the Palestinian limited component of female-headed National Cash Transfer Programme (PNCTP) in Gaza1 and households’ coping repertoires. West Bank2, as part of a broader research project in five countries (Kenya, Mozambique, OPT, Uganda and Yemen) by • Programme governance requires urgent the Overseas Development -

Annual Report #4

Fellow engineers Annual Report #4 Program Name: Local Government & Infrastructure (LGI) Program Country: West Bank & Gaza Donor: USAID Award Number: 294-A-00-10-00211-00 Reporting Period: October 1, 2013 - September 30, 2014 Submitted To: Tony Rantissi / AOR / USAID West Bank & Gaza Submitted By: Lana Abu Hijleh / Country Director/ Program Director / LGI 1 Program Information Name of Project1 Local Government & Infrastructure (LGI) Program Country and regions West Bank & Gaza Donor USAID Award number/symbol 294-A-00-10-00211-00 Start and end date of project September 30, 2010 – September 30, 2015 Total estimated federal funding $100,000,000 Contact in Country Lana Abu Hijleh, Country Director/ Program Director VIP 3 Building, Al-Balou’, Al-Bireh +972 (0)2 241-3616 [email protected] Contact in U.S. Barbara Habib, Program Manager 8601 Georgia Avenue, Suite 800, Silver Spring, MD USA +1 301 587-4700 [email protected] 2 Table of Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations …………………………………….………… 4 Program Description………………………………………………………… 5 Executive Summary…………………………………………………..…...... 7 Emergency Humanitarian Aid to Gaza……………………………………. 17 Implementation Activities by Program Objective & Expected Results 19 Objective 1 …………………………………………………………………… 24 Objective 2 ……………………................................................................ 42 Mainstreaming Green Elements in LGI Infrastructure Projects…………. 46 Objective 3…………………………………………………........................... 56 Impact & Sustainability for Infrastructure and Governance ……............ -

Winter 2017 Plus

WINTER 2017 PLUS. PLUS Winter 2017 1 WELCOME CLAYTON TRARALGON GEELONG (HEAD OFFICE) 25-27 Standing Drive Cnr Fyans & Crown Street 17-55 Nantilla Road Traralgon VIC 3844 Geelong South VIC 3220 Clayton VIC 3168 (03) 5175 6200 (03) 5223 5223 (03) 9566 0666 General Manager, Sales SWAN HILL LAVERTON DANDENONG 36-38 Curlewis Street 32-42 Spencer Street Swan Hill VIC 3585 Sunshine West VIC 3028 Ryan O’ Doherty 2-4 Fowler Rd, Dandenong South VIC 3175 (03) 5036 3900 (03) 9931 9666 (03) 9767 3600 BENDIGO TASMANIA MILDURA 11a Trantara Court 345 Benetook Avenue East Bendigo VIC 3550 (03) 5444 9199 LAUNCESTON Mildura VIC 3502 308 George Town Road (03) 5018 6100 Rocherlea TAS 7248 PORTLAND (03) 6325 0900 HORSHAM 167 Garden Street 81-83 Dimboola Road Portland VIC 3305 (03) 5521 5100 HOBART Horsham VIC 3400 2 Chardonnay Drive (03) 5362 4100 Berriedale TAS 7011 WODONGA (03) 6249 0566 SHEPPARTON 200 Melbourne Road 7847 Goulburn Valley Highway Wodonga VIC (02) 6051 5800 BURNIE Shepparton VIC 3631 Bass Highway (03) 5832 5500 Somerset TAS 7322 (03) 6433 8888 Designed by meg annabelle design Plus is published by William Adams PTY LTD as one of the many CAT PLUS services provided by your Caterpillar dealer in Victoria and Tasmania. All correspondence or requests for additions to our mailing list should be addressed to; Advertising and Promotion Department William Adams PTY LTD PO. Box 164, Clayton 3168, Australia (03) 9566 0666 1300 WADAMS williamadams.com.au Editorial content in this magazine can be reproduced in other media upon approval granted by William Adams’ advertising and promotion department. -

Construction Sector Technical Education and Skills

TRAINING REGULATIONS Heavy Equipment Operation (Bulldozer) NC II CONSTRUCTION SECTOR TECHNICAL EDUCATION AND SKILLS DEVELOPMENT AUTHOR ITY East Service Road, South Superhighway, Taguig City, Metro Manila BULLDOZER TR HEAVY - EQUIPMENT OPERATION (Bulldozer) Promulgated July 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS CONSTRUCTION - HEAVY EQUIPMENT SUB - SECTOR HEAVY EQUIPMENT OPERATION (BULLDOZER) NC II SECTION 1 HEAVY EQUIPMENT OPERATION QUALIFICATION SECTION 2 COMPETENCY STANDARDS SECTION 3 TRAINING STANDARDS 3.1 Curriculum Design 3. 2 Training Delivery 3.3 Trainee Entry Requirements 3.4 List of Tools, Equipment and Materials 3.5 Training Facilities 3.6 Trainers' Qualifications SECTION 4 ASSESSMENT AND CERTIFICATION ARRANGEMENT COMPETENCY MAP DEFINITION OF TERMS ACKNOWLEDGEMEN TS TR HEAVY - EQUIPMENT OPERATION (Bulldozer) Promulgated July 2007 TRAINING REGULATIONS FOR HEAVY EQUIPMENT OPERATION - BULLDOZER SECTION 1 HEAVY EQUIPMENT OPERATION - BULLDOZER The HEAVY EQUIPMENT OPERATION (BULLDOZER) NC II qualification consists of competencies that workers must achieve to enable them to perform tasks such as excavating, dozing, ripping, winching, and clearing of earth materials in construction sites or other locations. This qualification is packaged from the competency map of Construction - Heavy Equipment sub - sector as shown in Annex A. The units of competency comprising this qualification include the following: CODE NO. BASIC COMPETENCIES Units of Competency 500311105 Participate in workplace communication 500311106 Work in a team environment 500311107 Practice career professionalism 500311108 Practice occupational health and safety procedures CODE NO. COMMON COMPETENCIES Units of Competency CON931201 Prepare construction materials and tools CON311201 Observe procedures, specifications and manuals of inst ruction CON311202 Interpret technical drawings and plans CON311203 Perform mensurations and calculations CON311204 Maintain tools and equipment CODE NO. -

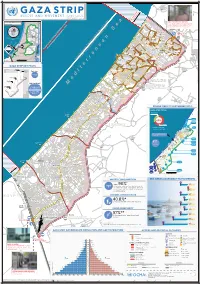

Gaza CRISIS)P H C S Ti P P I U

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory Zikim e Karmiya s n e o il Z P m A g l in a AGCCESSA ANDZ AMOV EMENTSTRI (GAZA CRISIS)P h c s ti P P i u F a ¥ SEPTEMBER 2014 o nA P N .5 F 1 Yad Mordekhai EREZ CROSSING (BEIT HANOUN) occupied Palestinian territory: ID a As-Siafa OPEN, six days (daytime) a B?week4 for B?3the4 movement d Governorates e e of international workers and limited number of y h s a b R authorized Palestinians including aid workers, medical, P r 2 e A humanitarian cases, businessmen and aid workers. Jenin d 1 e 0 Netiv ha-Asara P c 2 P Tubas r Tulkarm r fo e S P Al Attarta Temporary Wastewater P n b Treatment Lagoons Qalqiliya Nablus Erez Crossing E Ghaboon m Hai Al Amal r Fado's 4 e B? (Beit Hanoun) Salfit t e P P v i Al Qaraya al Badawiya i v P! W e s t R n m (Umm An-Naser) n i o » B a n k a North Gaza º Al Jam'ia ¹¹ M E D I TER RAN EAN Hatabiyya Ramallah da Jericho d L N n r n r KJ S E A ee o Beit Lahia D P o o J g Wastewater Ed t Al Salateen Beit Lahiya h 5 Al Kur'a J a 9 P l D n Treatment Plant D D D D 9 ) D s As Sultan D 1 2 El Khamsa D " Sa D e J D D l i D 0 D s i D D 0 D D d D D m 2 9 Abedl Hamaid D D r D D l D D o s D D a t D D c Jerusalem D D c n P a D D c h D D i t D D s e P! D D A u P 0 D D D e D D D a l m d D D o i t D D l i " D D n .