COL. John Ripley Interview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scott Gabriel Knowles, Ph.D

Scott Gabriel Knowles, Ph.D. Professor, Graduate School of Science and Technology Policy Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST) [email protected] Website: https://slowdisaster.com/ PROFESSIONAL Academic Positions 2021-current Professor, Graduate School of Science & Technology Policy, KAIST 2005-2021 Professor, Department of History, Drexel University 2004-2005 Visiting Assistant Professor, Department of History, John Jay College of Criminal Justice, City University of New York Research Positions and Affiliations 2019 Interuniversity Centre for the History of Science and Technology (CIUHCT), Nova University of Lisbon, Visiting Researcher 2018 Centro de Investigacion para la Gestion Integrada del Riesgo de Desastres (CIGIDEN), Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Visiting Researcher 2017 Korea Advanced Institute for Science and Technology (KAIST), Visiting Faculty 2016 Anthropocene Fellow, Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, Berlin (DAAD Grant—Visiting Scholar, July-August) 2016 Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society, Munich (DAAD Grant—Visiting Scholar, July) 2015 Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, Tokyo (JSPS Grant—Visiting Scholar, June-August) 2013-ongoing University of Pennsylvania Institute for Urban Research (Penn IUR), Faculty Fellow 2012-2019 University of Delaware, Disaster Research Center, Research Fellow 2006 Robert J. Lifton Fellow, John Jay College of Criminal Justice, Center on Terrorism 1 Administrative and Service Positions University 2013-2021 Head, -

Selected Biographies of Notable Marines

Selected Biographies of Notable Marines ___________________________________________________________________ Spanish-American War, Philippine Insurrection, Boxer Rebellion, Banana Wars, World War I Smedley D. Butler - Spanish-American War, Philippine Insurrection, Boxer Rebellion, Banana Wars, World War I • American Renegade: The Life and Times of Smedley Butler, USMC by Nate Braden • Smedley D. Butler, USMC: A Biography by Mark Strecker • Old Gimlet Eye, by Lowell Thomas Dan Daly – Boxer Rebellion, Banana Wars, World War I • Sergeant Major Dan Daly: The Most Outstanding Marine of All Time by Stephen W. Scott Hiram Bearss – Philippine Insurrection, World War I • Hiram Iddings Bearss, U.S. Marine Corps: Biography of a World War I Hero by George B. Clark John A. Lejeune – Spanish-American War, Philippine Insurrection, Banana Wars, World War I • Lejeune: A Marine's Life, 1867-1942 by Merrill L. Bartlett • The Reminiscences of a Marine, by Maj Gen John A. Lejeune ___________________________________________________________________ Banana Wars, World War I, World War II H.M. Smith • From Whaleboats to Amphibious Warfare: Lt. Gen. Howling Mad Smith and the U.S. Marine Corps by Anne Cipriano Venzon • A Fighting General, by Dr. Norman V. Cooper John W. Thomason • The World of Col John W. Thomason USMC, by Martha Anne Turner Pedro A. del Valle • Semper Fidelis, by LtGen Pedro A. del Valle, USMC ___________________________________________________________________ MCRD Command Museum 1600 Henderson Ave., Ste. 212, San Diego, CA 92140 www.usmchistory.org (619) 524-6719 Selected Biographies of Notable Marines ___________________________________________________________________ World War I, China Duty, World War II, Korea MajGen Gerald C. Thomas • In Many a Strife, by Allan R. Millett ___________________________________________________________________ Banana Wars, China Duty, World War II Alexander A. -

3Rd Battalion, 3Rdmarines Memories

3rd Battalion, 3rdMarines Aug 2010 Washington DC Memories America’s Battalion History - Honor - Tradition - Brotherhood Young Corpsmen … vintage Marines 3/3 at 29 Palms, March 2010 Why we gather together: There is a Bible scripture that states “There is no greater love than one who gives his life for another.” Many gave their lives that we could be here this evening. While we were spared by fate from giving our lives, we were prepared to do so for our fellow Marines and Docs. That’s the essence of Marine love and that’s why we did what we did. We cared for one another then as we do today. There’s nothing more to say. It would be unnecessary or redundant to say that we would trust our lives to one another—simply be- cause we have already have and in more ways that we could ever imagine or recount. We’re alive today be- cause of the quiet and unassuming courage and compassion of those in this room tonight as well as many or our comrades who are unable to be with us or who are with us only in spirit. That’s why we’ve come from great distances and, for some, at great expense. We’ll never be able to repay one another. There really isn’t enough money in the world to do that. But we will forever remember each other. That’s why we’re here. That’s why we’re so proud to have been a 3/3 Marine in Vietnam and so proud to be a part of this celebration of remembrance so many years later. -

Congressional Record—Senate S10723

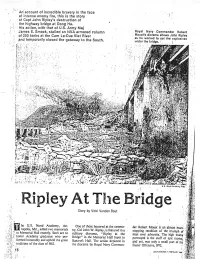

November 20, 2008 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE S10723 John Ripley is a symbol for the vi- have held against that North Vietnamese been a special friend to so many of us, and brancy of the Marine Corps, one of the force.’’ someone who is now moving on to a well de- most storied military forces in the The destruction of the bridge created a served retirement—Mike Kirk. Please join me in a round of applause to show our appre- globe’s history, and a testament to bottleneck for the North Vietnamese, allow- ing American bombers to blunt what became ciation for Mike and all that he has done. how—amid the enormity and vast con- known as the Easter offensive. We all know that Mike has done some very fusion of war—a single person can Captain Ripley was awarded the Navy special things for the AIPLA. But the best make a difference. Cross for his actions at the bridge. He served thing he did was to bring his wife, Mary I will miss seeing him at various two tours in Vietnam and remained on ac- Catherine, into our AIPLA family. I think events, including those of the Marine tive duty until 1992, eventually rising to she, too, deserves to be recognized for all she Corps Law Enforcement Foundation. colonel. Among other decorations, he re- has done. ceived the Silver Star, two Bronze Stars and One measure of a leader is the caliber of We will continue to honor his service the person selected to replace him. And here through support of the Marine Corps a Purple Heart. -

Class of 1962 Class of 19 62

Class of 1962 Class of 19 62 ohn W. Ripley was born in West Virginia. As a young man he Jenlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps, where his unique leadership qualities quickly became apparent. A year later, he earned an appointment to the United States Naval Academy as a member of the Class of 1962. At the academy, John excelled at meeting all types of challenges, setting a Brigade record for completion of the obstacle course. The Lucky Bag predicted when Rip returned to the Marines, he would be a fine addition to that service branch. After graduation John went to sea with the Marine detachment of USS Independence. He married Moline on May 9, 1964. Two years later, he reported to the Third Battalion, Third Marine Division in Vietnam, where he immediately engaged in dozens of combat operations. His strong leadership under hostile fire won him numerous citations and the respect of his men. By 1972, Colonel Ripley was among the few remaining American officers in Vietnam. On Easter Sunday, he single-handedly blew up a key bridge, stopping a North Vietnamese Army advance, earning John the Navy Cross and one of his Purple Hearts. In 1984, John was assigned to serve his alma mater, as Director, Division of English and History, and Senior Marine at the U.S. Naval Academy. The authors of the book The Marines recognized John as a “unique asset” to the Corps, with special qualifications in Airborne, SCUBA, Ranger, and the British Commando course. Though he retired from active duty in 1992, Colonel Ripley remains an important part of the Naval Academy, while heading the U.S. -

Hawaii HAZMAT A-3 Firefighter of the Year A-4 Lava Dogs A-5

INSIDE CG Mail A-2 Hawaii HAZMAT A-3 Firefighter of the Year A-4 Lava Dogs A-5 JVEF Contributions B-1 MCCS & SM&SP B-2 Menu B-4 Word To Pass B-5 Ads B-6 R.C. Airplanes C-1 MMARINEARINE Sports Briefs C-2 Volume 33, Number 35 www.mcbh.usmc.mil September 5, 2003 MCB Hawaii, safest in Corps again Cpl. Jason E. Miller mitment to the safety of all the cal situations. Marines training in Press Chief Marines and Sailors in Hawaii.” any of Hawaii’s training areas are Irvine and other key officials always accompanied by safety After yet another successful directly involved in earning the officials, whos only job is to look year aboard MCB Hawaii, award for the base have traveled out for the welfare of the Marines. Kaneohe Bay, the Base Safety to Washington D.C. to meet with The base safety center is also Center here has been honored by the Commandant of the Marine heavily involved in a traffic safety the Secretary of the Navy for the Corps, Gen. Michael Hagee and program and awareness package second consecutive year with the the Secretary of the Navy, the hon- that helps keep traffic accidents Department of the Navy Safety orable Hansford T. Johnson, to be aboard MCB Hawaii to a mini- Excellence Award for keeping the personally recognized for the mum. base as the safest in the Marine base’s achievements. “Winning is really a testament Corps . Marine Corps Base Hawaii has to the credibility of the command- “This is really a big thing,” said gained recognition Marine Corps ers and the Marines,” said Irvine. -

Tsm J. Napolis, Md., Added Two

>^'5 'AinnJi^ fci>.^««c£ilj4. 'SI w iu&M tSm Ml nc U.3. i^avai Acaaemy J. napolis, Md., added two mei to Memorial Hall recently. Both honor Academy graduates wh formed honorably and upheld th traditions of the class of 1962. : . 'Colonel Ripley, currently senior Ma- i. I. rl • V fine representative at the U.S. Naval i I! • . ! r •.' Academy, enlisted in the Corps in June of 1957. "I always Vk-anied to be .a Ma- .|i,, rine. There was never any oilier con- • 1 jf.-sideration," said Ripley. Fresh out of (I-: Radford High School, Radford, Va., ]!;• Ripley was deiermined to aa on,his not ' 'I so secret desire to be a Marine, j';' Jn recruit training, he found out a- i ' tout a program ihat put acdve duty sailors and Marines into the Nav^ I'. Academy Prep School prior to accep- •' lance into the Academy. Ripley was se- j lected for the program straight out of boot camp. "1 pursued this program. TTiat wasn't too easy because, ofcourse, ; anytime you identified yourselfas being interested in an officer program, well, the DIs went nuts!" Ripley remembers Col John Ripley'stood next to the diorama of his heroic effort to destroy the what the DIs would tell him. "They Dong Ha bridge. The diorama is In the foyer of ft/Jemorlal Hall at the U.S. Naval ! would yell, 'You haven't even gotten Academy, Annapolis, fWd. i through bootcamp yet!* Itsuregot me a A stint with theBridsh Royal Marines tour I had been out there 12 months," lot of unwanted attention. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—SENATE, Vol. 154, Pt. 18 November 20, 2008 Legal Aid Programs, Has Been an Enor- REMEMBERING COLONEL JOHN W

24326 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—SENATE, Vol. 154, Pt. 18 November 20, 2008 legal aid programs, has been an enor- REMEMBERING COLONEL JOHN W. Colonel Ripley, who at the time was a cap- mous success in securing legal rep- RIPLEY tain and a military adviser to a South Viet- namese Marine unit, blew up the southern resentation for lower-income Ameri- Mr. LEAHY. Mr. President, I regret cans. All 50 States have IOLTA pro- end of the Dong Ha Bridge over the Cua Viet to have to inform the Senate of the River on Easter Sunday, April 2, 1972. On the grams, and many States mandate par- passing of a truly great American: north side of the bridge, which was several ticipation by practicing attorneys. John W. Ripley, a retired Marine Corps miles south of the demilitarized zone, some This program provides funding to im- colonel and hero of the Vietnam war. 20,000 North Vietnamese troops and 200 tanks portant legal aid programs and helps Colonel Ripley will be best known for were poised to sweep into Quang Tri Prov- ensure that no person goes without his achievements and self-sacrifice dur- ince, which was sparsely defended. legal representation because of a lack ing the Vietnam war—particularly on Going back and forth for three hours while of resources. April 2, 1972, when he singlehandedly under fire, Captain Ripley swung hand over hand along the steel I-beams beneath the Our concern stems from the fact that blew up the Dong Ha bridge. That bridge, securing himself between girders and the TGLP Interim Rule concerning ac- bridge over the Cua Viet River was a placing crates holding a total of 500 pounds count insurance issued on October 23 major thoroughfare for an invasion of TNT in a diagonal line from one side of would not extend unlimited FDIC in- force from North Vietnam. -

Down to the Basics with Bozeman Joe Hanell Cadet Staff Writer a Real Supporter Primarily Involved People That Applied for the Job

VIRGINIA MILITARY INSTITUTE VOLUME LXXXVm FRIDAY, OCTOBER 21, 1994 NUMBER 9 Down to the Basics with Bozeman Joe Hanell Cadet Staff Writer a real supporter primarily involved people that applied for the job. No of myself as a with the special NCO's applied for the job. Sgt.Maj. Last June Gen. Knapp appointed track coach and projects and Maj. Goodson considered it but he had Col. Michael L. Bozeman as VMI's of the tfack pro- Simpson with the another tour that he had to extend for Commandant of the Corps of Ca- gram. When he training and opera- on the active duty side of the house. dets. He is a 1967 graduate of The asked me I tions aspect. He has a There were some civilians that ap- Citadel and has a master's degree found it really unique background plied that had prior service and were from the University of South Caro- difficult to say in that when he was working in law enforcement. But lina. Commissioned in 1967, he is no when he ap- here and with his ac- there were no other NCO's that did now a colonel in the United States parently needed tive duty extent and apply. So I don't look at it as getting Army Reserve. During his three years the help and had also as a National rid of an NCO position it's just a on active duty he served with dis- answered all Guard officer. Col. matter of bringing in the two best tinction as a platoon leader and for my objections Scott has a varied people that we could find to bring one tour commanded a long range as to why he background with the into the office. -

Chairman Tells VMI Grads Nation Needs Their Leadership Students

THEVOLUME INSTITUTE XXX, NUMBERREPORT, 7,MAY APRIL/MAY, 31, 2004, 2003PAGE 1 Volume XXXI, Number 8 May 31, 2004 Chairman Tells VMI Grads Nation Needs Their Leadership The two hundred and thirty-five “You don’t have to wear a cadets who received degrees uniform to serve,” he said. “There during the Institute’s are plenty of ways to serve. But for commencement exercise May 15 those of you who took the oath of enter a world that needs the office yesterday, much will be leadership they will provide. asked of you.” That was among the messages He was referring to the 93 cadets given them by Air Force Gen. who were commissioned as Richard B. Myers, chairman of the officers in the U.S. armed forces Joint Chiefs of Staff, in his the day prior to graduation. In commencement address in a addition, seven international crowded Cameron Hall. cadets were commissioned in the “This moment in the history of military services of their native our nation is far too important,” countries. he said. “The stakes are incredibly Cadet Matthew York ’04 General Richard Myers Myers said their talents as leaders high. We are fighting a war against will be needed in the military extremists who use terror as their preferred weapon.” service. He predicted many of the new graduates who enter military Speaking just two days after returning from a visit to Iraq, Myers said service will be deployed and will be asked to serve in harm’s way. he had confidence in Americans serving in the military and their leaders. -

RR2017 Packet

RIPLEY RACE RUN THE RACE, SUPPORT OUR VETERANS Benefing: stablished in 2009, the Ripley Race is a 5K road race and 1 mile Fun Run to raise awareness and support our soldiers returning from E war, while also honoring the legacy of Col. John Ripley, USMC (Ret). The event features the best 5K course in the Mid-AtlanKc region, a backdrop of Navy-Marine Corps Memorial Stadium, and a race course through the city of Annapolis, Maryland’s historic state capital, and post event party located at Fado Irish Pub with live music. ANNAPOLIS, MD NOVEMBER 12, 2017 WWW.RIPLEYRACE.COM Video: www.youtube.com/turningpointsports e are excited to enter into our 9th year with the Ripley Race! To date, we have raised over $350,000 from race parKcipaon and sponsors. Our event is rapidly growing into one of the largest 5K’s in the mid-AtlanKc area with almost 1,500 race parKcipants in 2016. We are expecKng another record turnout this fall. W The Semper Fi Fund (SFF) remains a primary beneficiary of the Ripley Race and we are honored and excited to be a part of this great cause. In 2016, we also added The Staon Foundaon (The Staon) as an addiKonal beneficiary, an organizaon focused on creang a balanced environment for Special Operaons forces returning home and entering civilian life. With the assistance of our Race Organizaon, Turning Point Sports, Ripley Race uKlizes its own 501(c)(3), the “Cincinnatus Fund Inc.,” in order to distribute donaons and race proceeds to SFF and The Staon. -

Tea and Sympathy W

142/DIALOGUE: A Journal of Mormon Thought Japanese immigrants in California. Similarly, the failure and rejection of Chris- tianity in China was due in part to the very un-Christian actions of "Christian" nations and nationals in China, who treated the Chinese as "heathen dogs," and practiced the Christian ethics of the pious Yankee skipper who refused to unload his shipload of opium on Sunday because it would violate the Sabbath. As Americans and as Mormons we need to subject ourselves to a careful evalu- ation of how our proposed solutions relate to the very special problems of differing cultures. In both political and religious endeavors, the willingness to recognize and respect the unique values of cultures other than our own, rather than to demand universal adherence in American cultural patterns, seems not only in our best in- terests, but also in harmony with the highest ideals of the gospel and of America. TEA AND SYMPATHY W. Roy Luce W. Roy Luce is a graduate student in Nineteenth Century U.S. History at Bngham Young University and teachers' quorum advisor in his L.D.S. ward. When I say to you the Mormons must go, I speak the mind of the camp and country. They can leave without force or injury to themselves or their property, but I say to you, Sir, with all candor, they shall go—they may fix the time within sixty days, or I will fix it for them.1 This statement, made in 1846 by Captain James W. Singleton, leader of an Illinois anti-Mormon group, is typical of the way many people felt about the Mor- mons during their forced exodus from Nauvoo, Illinois, to the west.