Marine Corps Generalship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to loe removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI* Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 WASHINGTON IRVING CHAMBERS: INNOVATION, PROFESSIONALIZATION, AND THE NEW NAVY, 1872-1919 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctorof Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Stephen Kenneth Stein, B.A., M.A. -

Inside Marine Barracks Hawaii Furls Flag After 90 Years Area Esbblished By

August 4, 1994 Vol. 22 No. 31 Serving Marine Forces Pacific, Marine Corps Base Hawaii, I sf MEB, and 1st Radio Battalion Marine Barracks Hawaii furls flag after 90 years Cpl. Bruce Drake sat Wriw While the music of the Marine Forces Pacific Band drifted across the parade deck in front of historic Puller Hall, Colonel W. W. North CH-46 celebrates its 30 officially disestablished Marine year anniversary with the Barracks Hawaii, Friday. Corpso,..See A-6 The ceremony marked not only the end of an era for Marine Bar- racks Hawaii, but the beginning of a new one as Marine Security Force Company, Pearl Harbor. Bicycle registration "This is not a sad moment or one in passing, as we are not completely If your bicycle was stolen from disestablishing the Marine presenCe your quarters or barracks, how at Pearl Harbor, but reassigning would you be able to identify it them to a new organization which to the military police? Of all will remain essential to the Navy- stolen bicycles reported to date, Marine Corps team," said Rear Adm. a disproportionate number are William Retz, commander of Naval not registered and/or secured. Base Pearl Harbor. Bicycles must be registered in "These Marines will continue the order to deter theft and locate traditions of excellence that have owners of those that are stolen. marked Marine Barracks Hawaii's The Hawaii Revised Statues service to Pearl Harbor," he added. requires all bicycles (and mopeds) Many in the crowd reflected on to be registered biannually. Each the history of the Barracks and its CO Bruce OnAs owner is furnished with a headquarters, future during thew short but sol- Final ceremony - A Marine color guard and platoon stand in front of Puller Hall, Marine Barrack Hawaii's metallic tag or decal for each emn morning ceremony. -

Interview with Peter Rafferty # VRV-A-L-2011-064.01 Interview # 1: December 15, 2011 Interviewer: Mark Depue

Interview with Peter Rafferty # VRV-A-L-2011-064.01 Interview # 1: December 15, 2011 Interviewer: Mark DePue COPYRIGHT The following material can be used for educational and other non-commercial purposes without the written permission of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library. “Fair use” criteria of Section 107 of the Copyright Act of 1976 must be followed. These materials are not to be deposited in other repositories, nor used for resale or commercial purposes without the authorization from the Audio-Visual Curator at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library, 112 N. 6th Street, Springfield, Illinois 62701. Telephone (217) 785-7955 Note to the Reader: Readers of the oral history memoir should bear in mind that this is a transcript of the spoken word, and that the interviewer, interviewee and editor sought to preserve the informal, conversational style that is inherent in such historical sources. The Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library is not responsible for the factual accuracy of the memoir, nor for the views expressed therein. We leave these for the reader to judge. DePue: Today is Thursday, December 15, 2011. My name is Mark DePue, the Director of Oral History with the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library. This morning I'm in the library, talking to Peter Rafferty. Good morning Pete. Rafferty: Good morning Mark. DePue: And you go by Pete, don't you? Rafferty: Yes I do. DePue: We are here to talk to Pete about his experiences as a Marine during the Vietnam War, during the very early stages of the Vietnam War. But, as I always do, I'd like to start off with a little bit about where and when you were born and learn a little bit about you, growing up. -

An Analysis of US Marine Corps Intelligence Modernization During

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-2017 Innovation in Intelligence: An Analysis of U.S. Marine Corps Intelligence Modernization during the Occupation of Haiti, 1915-1934 Laurence M. Nelson III Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Nelson, Laurence M. III, "Innovation in Intelligence: An Analysis of U.S. Marine Corps Intelligence Modernization during the Occupation of Haiti, 1915-1934" (2017). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 6536. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/6536 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INNOVATION IN INTELLIGENCE: AN ANALYSIS OF U.S. MARINE CORPS INTELLIGENCE MODERNIZATION DURING THE OCCUPATION OF HAITI, 1915-1934 by Laurence Merl Nelson III A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History Approved: ______________________ ____________________ Robert McPherson, Ph.D. James Sanders, Ph.D. Major Professor Committee Member ______________________ ____________________ Jeannie Johnson, Ph.D. Mark R. McLellan, Ph.D. Committee Member Vice President for Research and Dean of the School of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2017 ii Copyright © Laurence Merl Nelson III 2017 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Innovation in Intelligence: An Analysis of U.S. Marine Corps Intelligence Modernization during the Occupation of Haiti, 1915-1934 by Laurence M. -

Colby Alumnus Vol. 60, No. 1: Fall 1970

Colby College Digital Commons @ Colby Colby Alumnus Colby College Archives 1971 Colby Alumnus Vol. 60, No. 1: Fall 1970 Colby College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/alumnus Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Colby College, "Colby Alumnus Vol. 60, No. 1: Fall 1970" (1971). Colby Alumnus. 72. https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/alumnus/72 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the Colby College Archives at Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Alumnus by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Colby. COLBY COLLEGE LIBRARY Waterville, Maine 0 The Issue Fall 1970 f/111111·111111111g . I ht· \H·tkc11d l11lo11gC'd to J. li1·el)e ancl \f,11\ Bi,ln, .111d \\ould h,t\L t\tll if tile footli.dl 1l·:1m h.tcl llJ"t'l tilt· mo.,l powtilttl Bowdo111 'lf"·'d i11 lll< lll\ a )l':1r. (l L Ill.II I) did.) I he pH·,ide11t t•111t·1 itm .111cl hi., wife were ho1101ecl 011 Colin l'\1g ht. .111d 1c,po11dul ''ith the w.umth, chatm :t11cl wit whith d1.11';1ttc111ccl the 18 \it.ti Bl\.kr )Car� at Colb)- (Pages 1-3) The /5Jul cl11.11 a11it•1·1 .. I'rt�idc11t .Strider, in his tradi tional aclcln·.,� lo f1c.,hmu1 011 tlwi1 f11.,t cl.n 011 c.tmpus. <lb- c m�td ,..-h:1l the tollege "ffu., .111cl \\h.1t <.111 be C\.pectcd of '>tudt•11L-.: i11tl'llcctu:tl ch.tllu1gl. \Oti.tl ad.1ptil1ilit) .•1 rc'>pect fot Colb) ·, hcrit.1gc . -

Stogner Receives Navy Cross Medal in Polson

STOGNER RECEIVES NAVY CROSS MEDAL IN POLSON April 11, 2019 at 8:23 pm | By JOE SOVA Lake County Leader JAMES H. STOGNER, who served in the U.S. Marine Corps during the Vietnam War, received the prestigious Navy Cross Medal during a special ceremony Friday afternoon, April 5 at the VFW in Polson. The presentation was made by United States Marine Corps Lt. General Frank Libutti. (Joe Sova/Lake County Leader) SEN. STEVE Daines, second from left in the front row in the photo, was largely responsible for U.S. Marines Corporal James H. Stogner receiving the Navy Cross Medal at a ceremony Friday, April 5 at the Polson VFW. The meeting room was filled with supporters of Stogner and the military in general. (Joe Sova/Lake County Leader) JAMES H. STOGNER proudly wears the Navy Cross Medal that he received during the April 5 ceremony at the Polson VFW. James H. Stogner, a former Polson resident who now lives in Thompson Falls, received the prestigious Navy Cross Medal during a special ceremony Friday afternoon, April 5 at the VFW in Polson. Lance Corp. Stogner served in the U.S. Marine Corps during the Vietnam War. The presentation, which was facilitated by Montana Sen. Steve Daines and his office, was made by United States Marine Corps Lt. General Frank Libutti. Daines served as master of ceremonies for the well-attended event. April 5 of this year, the date of the commendation, marked the 52nd anniversary of the day when Stogner showed extraordinary heroism and courage while rescuing a fellow Marine. -

HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES Charles K

l1146 CQNGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE DECEMBER 8 Officers of the Supply Corps · Clifton B. Cates Lemuel C. Shepherd~ To Be Commanders Leo D. Hermie . Jr. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Charles K. Phillips To be brigadier generals MONDAY, DECEMBER 8, 1947 Allen .B. Reed, Jr. · Alfred H. Noble Omar T. Pfeiffer Officers of the Dentat Corps Graves B. Erskine William E. Riley The House met at 12 o'clock noon. To Be Commanders Louis E. Woods Merwin H. Silverthorn Franklin A. Hart Ray A. Robinson The Chaplain, Rev. James Shera John P. Jarabak Field Harris Gerald C. Thomas Montgomery, D. D., offered the follow Herman K. Rendtorff William J. Wallace Henry D. Linscott ing prayer: Robert D. Wyckoff Oliver P. Smith Dudley S. Brown Almighty God, our Father, we bring Officers of the line Robert Blake Robert H. Pepper our sins and our virtues into Thy re To Be Lieutenant Commanders William A. Worton William P. T. Hill William T. Clement Andrew E. Creesy vealing light and pray Thee to skill us John L. Hutchinson Ogle W. Price, Jr. Louis R. Jones Leonard E. Rea in those purposes which make for a world Walter F. V. Bennett William E. Hoppe John T. Walker Merritt B. Curtis of love, of contentment and peace. Be James F. Wheeler Robert M. Ross Francis A. Lewis William J. Hagerty The following-named officers for appoint not far away, but continue to create Frederick W. Zigler Harry S. Warren ment in the United States Marine Corps in within us the ·finest conceptions of duty Willard H. Davidson James H. -

Spearhead-Fall-Winter-2019.Pdf

Fall/Winter 2019 SpearheadOFFICIAL PUBLICATION of the 5TH MARINE DIVISION NEWS“Uncommon Valor was a Common Virtue” ASSOCIATION OCTOBER 22 - 25, 2020 71ST ANNUAL REUNION DALLAS, TEXAS Sons of Iwo vets take the helm of FMDA Bruce Hammond and statue in Semper Fi Tom Huffhines, both Memorial Park at the native Texans and sons Marine Corps War of Iwo Jima veterans Museum at Quantico, who previously (Triangle) Va., and served as Association had long worked with presidents and reunion the FMDA. hosts, were selected to Continuing his lead the Fifth Marine father’s work with the Division Association Association, President as president and vice Bruce Hammond said, president, respectively, “It is important that we for the next year. channel our passion, Additionally, move forward and lifetime FMDA mem- President Bruce Hammond and Vice President Tom Huffhines focus on our mission ber, Army helicopter for our Marine veterans.” pilot and Vietnam veteran John Powell volunteered to Vice President John Huffhines agreed and said, host the next FMDA reunion from Oct. 22-25, 2020, in “Communication with the membership, as good and Dallas. as often as possible, is extremely key to its existence. Hammond’s father, Ivan (5th JASCO), hosted the Stronger fundraising ideas and efforts should be the 2016 reunion in San Antonio, Texas, when John Butler main thing on each of our agendas.” was president, and in Houston, Texas, in 2009 when he Hammond graduated from the University of Texas, was president himself. Austin, in 1989 with a bachelor’s degree in psychology. Huffhines’ father, John (HS 2/3), hosted the 2006 He worked for 24 years as a well-site drilling-fluids reunion in Irving, Texas, when he was president. -

Trump's Generals

STRATEGIC STUDIES QUARTERLY - PERSPECTIVE Trump’s Generals: A Natural Experiment in Civil-Military Relations JAMES JOYNER Abstract President Donald Trump’s filling of numerous top policy positions with active and retired officers he called “my generals” generated fears of mili- tarization of foreign policy, loss of civilian control of the military, and politicization of the military—yet also hope that they might restrain his worst impulses. Because the generals were all gone by the halfway mark of his administration, we have a natural experiment that allows us to com- pare a Trump presidency with and without retired generals serving as “adults in the room.” None of the dire predictions turned out to be quite true. While Trump repeatedly flirted with civil- military crises, they were not significantly amplified or deterred by the presence of retired generals in key roles. Further, the pattern continued in the second half of the ad- ministration when “true” civilians filled these billets. Whether longer-term damage was done, however, remains unresolved. ***** he presidency of Donald Trump served as a natural experiment, testing many of the long- debated precepts of the civil-military relations (CMR) literature. His postelection interviewing of Tmore than a half dozen recently retired four- star officers for senior posts in his administration unleashed a torrent of columns pointing to the dangers of further militarization of US foreign policy and damage to the military as a nonpartisan institution. At the same time, many argued that these men were uniquely qualified to rein in Trump’s worst pro- clivities. With Trump’s tenure over, we can begin to evaluate these claims. -

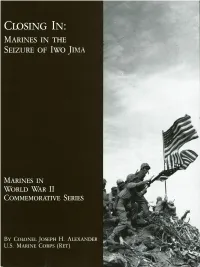

Closingin.Pdf

4: . —: : b Closing In: Marines in the Seizure of Iwo Jima by Colonel Joseph H. Alexander, USMC (Ret) unday, 4 March 1945,sion had finally captured Hill 382,infiltrators. The Sunday morning at- marked the end of theending its long exposure in "The Am-tacks lacked coordination, reflecting second week ofthe phitheater;' but combat efficiencythe division's collective exhaustion. U.S. invasion of Iwohad fallen to 50 percent. It wouldMost rifle companies were at half- Jima. By thispointdrop another five points by nightfall. strength. The net gain for the day, the the assault elements of the 3d, 4th,On this day the 24th Marines, sup-division reported, was "practically and 5th Marine Divisions were ex-ported by flame tanks, advanced anil." hausted,their combat efficiencytotalof 100 yards,pausingto But the battle was beginning to reduced to dangerously low levels.detonate more than a ton of explo-take its toll on the Japanese garrison The thrilling sight of the Americansives against enemy cave positions inaswell.GeneralTadamichi flag being raised by the 28th Marinesthat sector. The 23d and 25th Ma-Kuribayashi knew his 109th Division on Mount Suribachi had occurred 10rines entered the most difficult ter-had inflicted heavy casualties on the days earlier, a lifetime on "Sulphurrain yet encountered, broken groundattacking Marines, yet his own loss- Island." The landing forces of the Vthat limited visibility to only a fewes had been comparable.The Ameri- Amphibious Corps (VAC) had al-feet. can capture of the key hills in the ready sustained 13,000 casualties, in- Along the western flank, the 5thmain defense sector the day before cluding 3,000 dead. -

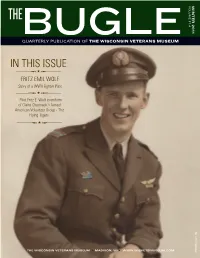

In This Issue

VOLUME 17:4 2011 WINTER IN THIS ISSUE FRITZ EMIL WOLF Story of a WWII Fighter Pilot Pilot Fritz E. Wolf in uniform of Claire Chennault’s famed American Volunteer Group - The Flying Tigers. THE WISCONSIN VETERANS MUSEUM MADISON, WI WWW.WISVETSMUSEUM.COM WVM Mss 2011.102 FROM THE DIRECTOR Wisconsin Veterans Museum. How soldier in the 7th Wisconsin. He may could it be otherwise? We are sur- have read about the Iron Brigade rounded by things that resonate in books, but the idea of advancing with stories of Wisconsin’s veterans. shoulder to shoulder in line of battle In this issue you will read stories under musket and cannon fire was about three men who, although sep- a relic of a far away past. Likewise, arated by time, embody commonly Hunt could never have imagined held traits that link them together Wolf’s airplane, let alone land- among a long line of veterans. We ing one on the deck of a ship. As a start with the account of the in- resident of Kenosha, Isermann may trepid naval combat flying ace Fritz have known veterans of Hunt’s Iron Wolf, a native of Madison by way of Brigade, but their ancient exploits Shawano, Wisconsin who flew with were long ago events separated by Claire Chennault’s Flying Tigers in more than fifty years from the Great China, and later with the US Navy. War. To a twentieth century man Wolf’s story is followed by the tragic engaged in WWI naval operations, account of an English immigrant, Gettysburg might as well have been John Hunt, who settled in Wiscon- Thermopylae. -

The Long Island Historical Journal

THE LONG ISLAND HISTORICAL JOURNAL United States Army Barracks at Camp Upton, Yaphank, New York c. 1917 Fall 2003/ Spring 2004 Volume 16, Nos. 1-2 Starting from fish-shape Paumanok where I was born… Walt Whitman Fall 2003/ Spring 2004 Volume 16, Numbers 1-2 Published by the Department of History and The Center for Regional Policy Studies Stony Brook University Copyright 2004 by the Long Island Historical Journal ISSN 0898-7084 All rights reserved Articles appearing in this journal are abstracted and indexed in Historical Abstracts and America: History and Life The editors gratefully acknowledge the support of the Office of the Provost and of the Dean of Social and Behavioral Science, Stony Brook University (SBU). We thank the Center for Excellence and Innovation in Education, SBU, and the Long Island Studies Council for their generous assistance. We appreciate the unstinting cooperation of Ned C. Landsman, Chair, Department of History, SBU, and of past chairpersons Gary J. Marker, Wilbur R. Miller, and Joel T. Rosenthal. The work and support of Ms. Susan Grumet of the SBU History Department has been indispensable. Beginning this year the Center for Regional Policy Studies at SBU became co-publisher of the Long Island Historical Journal. Continued publication would not have been possible without this support. The editors thank Dr. Lee E. Koppelman, Executive Director, and Ms. Edy Jones, Ms. Jennifer Jones, and Ms. Melissa Jones, of the Center’s staff. Special thanks to former editor Marsha Hamilton for the continuous help and guidance she has provided to the new editor. The Long Island Historical Journal is published annually in the spring.