Missionary Perspectives and Experiences of 19Th and Early

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nation- and Image Building by the Rehoboth Basters

Nation- and Image Building by the Rehoboth Basters Negative bias concerning the Rehoboth Basters in literature Jeroen G. Zandberg Nation- and Image Building by the Rehoboth Basters Negative bias concerning the Rehoboth Basters in literature 1. Introduction Page 3 2. How do I define a negative biased statement? …………………..5 3. The various statements ……………………………………… 6 3.1 Huibregtse ……………………………………… ……. 6 3.2 DeWaldt ……………………………………………. 9 3.3 Barnard ……………………………………………. 12 3.4 Weiss ……………………………………………. 16 4. The consequences of the statements ………………………… 26 4.1 Membership application to the UNPO ……………27 4.2 United Nations ………………………………………29 4.3 Namibia ……………………………………………..31 4.4 Baster political identity ………………………………..34 5. Conclusion and recommendation ……………………………...…38 Bibliography …………………………………………………….41 Rehoboth journey ……………………………………………...43 Picture on front cover: The Kapteins Council in 1876. From left to right: Paul Diergaardt, Jacobus Mouton, Hermanus van Wijk, Christoffel van Wijk. On the table lies the Rehoboth constitution (the Paternal Laws) Jeroen Gerk Zandberg 2005 ISBN – 10: 9080876836 ISBN – 13: 9789080876835 2 1. Introduction The existence of a positive (self) image of a people is very important in the successful struggle for self-determination. An image can be constructed through various methods. This paper deals with the way in which an incorrect image of the Rehoboth Basters was constructed via the literature. Subjects that are considered interesting or popular, usually have a great number of different publications and authors. A large quantity of publications almost inevitably means that there is more information available on that specific topic. A large number of publications usually also indicates a great amount of authors who bring in many different views and interpretations. -

Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2021 “Remov[e] Us From the Bondage of South Africa:” Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962 Michael R. Hogan West Virginia University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the African History Commons Recommended Citation Hogan, Michael R., "“Remov[e] Us From the Bondage of South Africa:” Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962" (2021). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 8264. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/8264 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Remov[e] Us From the Bondage of South Africa:” Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962 Michael Robert Hogan Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In History Robert M. -

Missionary Perspectives and Experiences of 19Th and Early 20Th Century Droughts

1 2 “Everything is scorched by the burning sun”: Missionary perspectives and 3 experiences of 19th and early 20th century droughts in semi-arid central 4 Namibia 5 6 Stefan Grab1, Tizian Zumthurm,2,3 7 8 1 School of Geography, Archaeology and Environmental Studies, University of the 9 Witwatersrand, South Africa 10 2 Institute of the History of Medicine, University of Bern, Switzerland 11 3 Centre for African Studies, University of Basel, Switzerland 12 13 Correspondence to: Stefan Grab ([email protected]) 14 15 Abstract. Limited research has focussed on historical droughts during the pre-instrumental 16 weather-recording period in semi-arid to arid human-inhabited environments. Here we describe 17 the unique nature of droughts over semi-arid central Namibia (southern Africa) between 1850 18 and 1920. More particularly, our intention is to establish temporal shifts of influence and 19 impact that historical droughts had on society and the environment during this period. This is 20 achieved through scrutinizing documentary records sourced from a variety of archives and 21 libraries. The primary source of information comes from missionary diaries, letters and reports. 22 These missionaries were based at a variety of stations across the central Namibian region and 23 thus collectively provide insight to sub-regional (or site specific) differences in hydro- 24 meteorological conditions, and drought impacts and responses. Earliest instrumental rainfall 25 records (1891-1913) from several missionary stations or settlements are used to quantify hydro- 26 meteorological conditions and compare with documentary sources. The work demonstrates 27 strong-sub-regional contrasts in drought conditions during some given drought events and the 28 dire implications of failed rain seasons, the consequences of which lasted many months to 29 several years. -

MISSION APOLOGETICS: the RHENISH MISSION from WARS and GENOCIDE to the NAZI REVOLUTION, 1904-1936 GLEN RYLAND MOUNT ROYAL UNIVERSITY [email protected]

STORIES AND MISSION APOLOGETICS: THE RHENISH MISSION FROM WARS AND GENOCIDE TO THE NAZI REVOLUTION, 1904-1936 GLEN RYLAND MOUNT ROYAL UNIVERSITY [email protected] tories of a Herero woman, Uerieta Kaza- Some Germans even met her face-to-face when Shendike (1837-1936), have circulated for a she visited the Rhineland and Westphalia with century and a half among German Protestants in missionary Carl Hugo Hahn in 1859, a year the Upper Rhineland and Westphalian region. after her baptism.2 Other than a few elites, no Known to mission enthusiasts as Johanna other Herero received as much written attention Gertze, or more often “Black Johanna” from the missionaries as Uerieta did. Why was (Schwarze Johanna), Uerieta was the first her story of interest to missions-minded Protest- Herero convert of the Rhenish Mission Society. ants in Germany? By 1936, her life had spanned the entire period In 1936, missionary Heinrich Vedder again of the Herero mission she had served since her told her story, this time shaping her into an youth. Over the years, the mission society African heroine for the Rhenish Mission. In published multiple versions of her story Vedder’s presentation “Black Johanna” demon- together with drawings and photos of her.1 strated the mission’s success in the past and embodied a call for Germans in the new era of National Socialism to do their duty toward so- called inferior peoples. Vedder used Uerieta’s I am grateful to Dr. Doris L. Bergen, Chancellor Rose story to shape an apologetic for Protestant mis- and Ray Wolfe Professor of Holocaust Studies, Uni- sions within the new regime. -

Missionary Perspectives and Experiences of 19Th And

1 2 “Everything is scorched by the burning sun”: Missionary perspectives and 3 experiences of 19 th and early 20 th century droughts in semi-arid central 4 Namibia 5 6 Stefan Grab 1, Tizian Zumthurm ,2,3 7 8 1 School of Geography, Archaeology and Environmental Studies, University of the 9 Witwatersrand, South Africa 10 2 Institute of the History of Medicine, University of Bern, Switzerland 11 3 Centre for African Studies, University of Basel, Switzerland 12 13 Correspondence to : Stefan Grab ( [email protected] ) 14 15 Abstract. Limited research has focussed on historical droughts during the pre-instrumental 16 weather-recording period in semi-arid to arid human-inhabited environments. Here we describe 17 the unique nature of droughts over semi-arid central Namibia (southern Africa) between 1850 18 and 1920. More particularly, our intention is to establish temporal shifts of influence and 19 impact that historical droughts had on society and the environment during this period. This is 20 achieved through scrutinizing documentary records sourced from a variety of archives and 21 libraries. The primary source of information comes from missionary diaries, letters and reports. 22 These missionaries were based at a variety of stations across the central Namibian region and 23 thus collectively provide insight to sub-regional (or site specific) differences in hydro- 24 meteorological conditions, and drought impacts and responses. Earliest instrumental rainfall 25 records (1891-1913) from several missionary stations or settlements are used to quantify hydro- 26 meteorological conditions and compare with documentary sources. The work demonstrates 27 strong-sub-regional contrasts in drought conditions during some given drought events and the 28 dire implications of failed rain seasons, the consequences of which lasted many months to 29 several years. -

Washington, D.C

SUPERIOR COURT OF THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIVIL DIVISION THE HERERO PEOPLE’S REPARATIONS CORPORATION, : a District of Columbia Corporation : 1625 K Street, NW, #102 : Washington, D.C. 20006 : : THE HEREROS, : a Tribe and Ethnic and Racial Group, : by and through its Paramount Chief : By Paramount Chief Riruako : Paramount Chief K. Riruako : P.O. Box 60991 Katutura : Windhoek, Republic of Namibia 9000 : Mburumba Getzen Kerina : P.O. Box 24861 : Windhoek, Republic of Namibia 9000 : Kurundiro Kapuuo : Case No. 01-0004447 Box 24861 : Windhoek, Republic of Namibia 9000 : Judge Jackson Calendar 2 Cornelia Tjaveondja : Next Scheduled Event: P.O. Box 24861 : Initial Scheduling Conference Windhoek, Republic of Namibia 9000 : September 18, 2001 at 9:30 a.m. Moses Nguarambuka : P.O. Box 24861 : Windhoek, Republic of Namibia 9000 : Hilde Kazakoka Kamberipa : SQ66 Genesis Street : P.O. Box 61831 : Windhoek, Republic of Namibia 9000 : Festus Korukuve : P.O. Box 50 : Opuuo (Otuzemba), Namibia : Uezuvanjo Tjihavgc : Box 27 : Opuuo, Namibia : Ujeuetu Tjihange : Box 27 : Opuuo, Namibia : Moses Katuuo : P.O. Box 930 : Gobabis, Namibia 9000 : Levy K. O. Nganjone : P.O. Box 309 : Gobabis, Namibia : Festus Ndjai : Opuuo, Namibia : Hoomajo Jjingee : Opuuo, Namibia : Uelembuia Tjinawba : Okandombo : Okunene Region, Namibia : Jararaihe Tjingee : Opuuo, Namibia : Hangekaoua Mbinge : Opuuo, Namibia : Ehrens Jeja : Box 210 : Omaruru : Omatjete, Namibia : Nathanael Uakumbua : Box 211 : Omaruru, Namibia : Rudolph Kauzuu : Box 210 : Omatjete : Omaruru, Namibia : 2 Jaendekua Kapika : Opuuo, Namibia : Ben Mbeuserua : P.O. Box 224 : Okakarara, Namibia 9000 : Felix Kokati : Box 47 : Okakarara, Namibia 9000 : Samuel Upendura : Oyinene : Omaheke Region, Namibia : Majoor Festus Kamburona : P.O. 1131 : Windhoek, Republic of Namibia 9000 : Uetavera Tjirambi : Okonmgo : Okanene Region, Namibia : Julius Katjingisiua : P.O. -

The Transformation of the Lutheran Church in Namibia

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2009 The Transformation of the Lutheran Church in Namibia Katherine Caufield Arnold College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Arnold, Katherine Caufield, "The rT ansformation of the Lutheran Church in Namibia" (2009). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 251. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/251 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Introduction Although we kept the fire alive, I well remember somebody telling me once, “We have been waiting for the coming of our Lord. But He is not coming. So we will wait forever for the liberation of Namibia.” I told him, “For sure, the Lord will come, and Namibia will be free.” -Pastor Zephania Kameeta, 1989 On June 30, 1971, risking persecution and death, the African leaders of the two largest Lutheran churches in Namibia1 issued a scathing “Open Letter” to the Prime Minister of South Africa, condemning both South Africa’s illegal occupation of Namibia and its implementation of a vicious apartheid system. It was the first time a church in Namibia had come out publicly against the South African government, and after the publication of the “Open Letter,” Anglican and Roman Catholic churches in Namibia reacted with solidarity. -

Land Reform Is Basically a Class Issue”

This land is my land! Motions and emotions around land reform in Namibia Erika von Wietersheim 1 This study and publication was supported by the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Namibia Office. Copyright: FES 2021 Cover photo: Kristin Baalman/Shutterstock.com Cover design: Clara Mupopiwa-Schnack All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, copied or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system without the written permission of the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. First published 2008 Second extended edition 2021 Published by Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Namibia Office P.O. Box 23652 Windhoek Namibia ISBN 978-99916-991-0-3 Printed by John Meinert Printing (Pty) Ltd P.O. Box 5688 Windhoek / Namibia [email protected] 2 To all farmers in Namibia who love their land and take good care of it in honour of their ancestors and for the sake of their children 3 4 Acknowledgement I would like to thank the Friedrich-Ebert Foundation Windhoek, in particular its director Mr. Hubert Schillinger at the time of the first publication and Ms Freya Gruenhagen at the time of this extended second publication, as well as Sylvia Mundjindi, for generously supporting this study and thus making the publication of ‘This land is my land’ possible. Furthermore I thank Wolfgang Werner for adding valuable up-to-date information to this book about the development of land reform during the past 13 years. My special thanks go to all farmers who received me with an open heart and mind on their farms, patiently answered my numerous questions - and took me further with questions of their own - and those farmers and interview partners who contributed to this second edition their views on the progress of land reform until 2020. -

Flags, Funerals and Fanfares: Herer O and Missionary Contestations Ofthe Acceptable, 1900-1940 *

Journal ofAfrican Cultural Studies, Volume 15, Number l, June 2002 Carfax Publishing Taylor & Franc« Group Flags, funerals and fanfares: Herer o and missionary contestations ofthe acceptable, 1900-1940 * JAN-BART GEWALD (Institute for African Studies, University of Cologne) ABSTRACT The article describes the contested relationship that existed between Herero people and German missionaries in Namibia between 1900 and 1940. 1t is argued that Herero converted to mission Christianity with specific aims and intentions, which were not necessarily the same as those envisaged or intended by German missionaries. The article highlights leisure time, commemorative activities and funerals, and indicates that Herero acquired specific forms of music, dress, comportment, and behaviour from German missionaries. Once these specific forms were acquired they were often transformed and brought to the f ore in ways that were considered unacceptable by the missionaries and settler society in general. The article shows that apart from race there was little difference in the intentions and activities of Herero and German settlers, both ofwhom sought to influence the same'colonial administration. In conclusion it is argued that, in the last resort, what was ofprimary importance in the colonial setting of Namibia between 1900 and 1940 was the issue of race. On a wintry Sunday morning in 1927, a missionary working in the small settlement of Otjimbingwe in Namibia found his early-morning devotional ministrations rudely disturbed by the stridently noisy arrival of a football team from the neighbouring town of Karibib. Borne on trucks bearing flags in the 'colours of the Ethiopian freedom movement' and singing songs, the young men and their supporters began a boisterous day of competition, and ensured that the missionary had but a paltry few church attendants. -

Application No: APP-001418

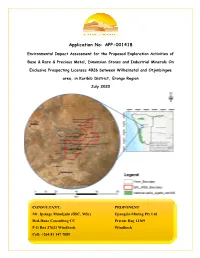

Application No: APP-001418 Environmental Impact Assessment for the Proposed Exploration Activities of Base & Rare & Precious Metal, Dimension Stones and Industrial Minerals On Exclusive Prospecting Licenses 4926 between Wilhelmstal and Otjimbingwe area, in Karibib District, Erongo Region July 2020 CONSULTANT: PROPONENT Mr. Ipeinge Mundjulu (BSC, MSc) Epangelo Mining Pty Ltd Red-Dune Consulting CC Private Bag 13369 P O Box 27623 Windhoek Windhoek Cell: +264 81 147 7889 DOCUMENT INFORMATION DOCUMENT STATUS FINAL APPLICATION NO: APP-001418 PROJECT TITLE Environmental Impact Assessment for the Proposed Exploration Activities of Base & Rare & Precious Metal, Dimension Stones and Industrial Minerals On Exclusive Prospecting Licenses 4926 CLIENT Epangelo Mining Pty Ltd PROJECT CONSULTANT Mr. Ipeinge Mundjulu LOCATION Between Wilhelmstal and Otjimbingwe area, in Karibib District, Erongo Region Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ ii 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 1 1.1. Regulatory Requirements ................................................................................................. 1 1.2. The Need and Desirability of the Project ......................................................................... 2 1.3. Terms of Reference ......................................................................................................... -

I the EVANGELICAL LUTHERAN CHURCH

THE EVANGELICAL LUTHERAN CHURCH IN NAMIBIA (ELCIN) AND POVERTY, WITH SPECIFIC REFERENCE TO SEMI-URBAN COMMUNITIES IN NORTHERN NAMIBIA - A PRACTICAL THEOLOGICAL EVALUATION by Gideon Niitenge Dissertation Presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in PRACTICAL THEOLOGY (COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT) at the University of Stellenbosch Promoter: Prof Karel Thomas August March 2013 i Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za DECLARATION I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this dissertation is my own original work and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part been submitted it at any university for a degree. Signed: _______________________ Date_________________________ Copyright © 2013 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved ii Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za DEDICATION I dedicate this work to the loving memory of my late mother Eunike Nakuuvandi Nelago Iiputa (Niitenge), who passed away while I was working on this study. If mom was alive, she could share her joy with others to see me completing this doctoral study. iii Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za ABBREVIATIONS AIDS Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome ARV Anti-Retroviral Treatment AFM Apostolic Faith Mission ACSA Anglican Church of Southern Africa AAP Anglican AIDS Programme AGM Annual General Meeting AMEC African Methodist Episcopal Church CAA Catholic AIDS Action CBO Community-Based Organisation CCDA Christian Community Development Association CAFO Church Alliance for Orphans CUAHA Churches United Against -

Restoration of the Land to Its Rightful Owners

WORKERS REVOLUTIONARY PARTY DRAFT PROPOSAL TO THE WORKING PEOPLE OF NAMIBIA AND SOUTHERN AFRICA FOR THE RESTORATION OF THE LAND TO ITS RIGHTFUL OWNERS OUR POSITION In 1884. the German Reich. illegally in terms of international law. colonised independent nations which already held their own demarcated lands under their own laws. lt had nothing to do with ancestrallands.lt was their own property in law and natural reality. Marxist Considerations on the Crisis: Nothing that occurred from 1884 to 1990 in the colonisation of Namibia has legalised the expropriation of lands of the occupied Part 1 peoples. We say that legality must be restored before there can be by Balazs Nagy Published for Workers International by Socialist talk of the rule of law. The nations of Namibia are entitled to the restoration of their expropriated lands. Studies, isbn 978 0 9564319 3 6 Cognisant of the fundamental changes in Namibian society in terms of economic and social classes. in particular rural and urban The Hungarian Marxist BALAZS NAGY originally planned workers. brought by colonialism and capitalism. the WRP calls for this work as 'an article explaining the great economic crisis a National Conference of all interested parties (classes) to put their which erupted in 2007 from a Marxist point of view'. respective positions for debate and democratic decision. lt is in the interest of the working class and poor peasantry in However, he 'quite quickly realised that a deeper particular to neutralise the propaganda advantage which imperial understanding of this development would only be possible ism holds over land reform through the perversion of "expropriation if I located it within a broader historical and political without compensation" by black middle classes.