Sea Scout Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Armed Sloop Welcome Crew Training Manual

HMAS WELCOME ARMED SLOOP WELCOME CREW TRAINING MANUAL Discovery Center ~ Great Lakes 13268 S. West Bayshore Drive Traverse City, Michigan 49684 231-946-2647 [email protected] (c) Maritime Heritage Alliance 2011 1 1770's WELCOME History of the 1770's British Armed Sloop, WELCOME About mid 1700’s John Askin came over from Ireland to fight for the British in the American Colonies during the French and Indian War (in Europe known as the Seven Years War). When the war ended he had an opportunity to go back to Ireland, but stayed here and set up his own business. He and a partner formed a trading company that eventually went bankrupt and Askin spent over 10 years paying off his debt. He then formed a new company called the Southwest Fur Trading Company; his territory was from Montreal on the east to Minnesota on the west including all of the Northern Great Lakes. He had three boats built: Welcome, Felicity and Archange. Welcome is believed to be the first vessel he had constructed for his fur trade. Felicity and Archange were named after his daughter and wife. The origin of Welcome’s name is not known. He had two wives, a European wife in Detroit and an Indian wife up in the Straits. His wife in Detroit knew about the Indian wife and had accepted this and in turn she also made sure that all the children of his Indian wife received schooling. Felicity married a man by the name of Brush (Brush Street in Detroit is named after him). -

Troop Ideas: October Girl Scout Tradition Activities

GSKSMO Girl Scouts Virtual | Daisies Troop Ideas: October Girl Scout Tradition Activities Troop meeting activities for Daisies Welcome back to Girl Scouts! This month we focus on Girl Scout traditions. Sharing traditions gives Girl Scouts a sense of history and it reminds girls they are part of a greater sisterhood. The Girl Scout Promise and Law have been the Foundation of our Movement from the very beginning in 1912 and is something we share with Girl Guides and Girl Scouts around the world. For more on the Girl Scout Promise and Law please check out our August Virtual Content https://www.gsksmo.org/content/dam/girlscouts-gsksmo/documents/tlc- docs/Promise-and-Law-Daisy-Brownie-Leader-Resources.pdf Try one or more of these activities Meeting activity: Virtual adaptation: Teach the Girl Scout Sign Teach the Girl Scout Sign • Girls raise three fingers of the right hand with the • Take a picture of individual girls or on a Zoom thumb holding down the pinky— this is normally call and create a collage of everybody doing done when they say the Girl Scout Promise. the Girl Scout Sign • The three fingers represent the three parts of the • Try out this Girl Scout Promise Craft from our Promise. August content - https://www.gsksmo.org/content/dam/girlsco uts-gsksmo/OtherDocuments/virtual/Promise- Craft.pdf Teach the Girl Scout Handshake Teach the Girl Scout Handshake • The handshake is made by shaking hands with the • Practice the Girl Scout Handshake with a left hand and making the Girl Scout sign with the member of your household right. -

Member Orientation Package Revised 2015

SUS Member Orientation Package Revised 2015 We welcome you to Singles Under Sail, Inc. SUS members are required to meet certain education requirements. It is mandatory for all NEW members to have met the following requirements by their second membership renewal date: 1) To have completed the SUS Dockside Orientation Class (DOC), AND 2) To have passed either the U.S. Coast Guard Auxiliary's or the U.S. Power Squadron's Basic Boating Course (8 hours minimum), OR provide proof of having held a U.S. Coast Guard Captain’s license, AND 3) To attend an SUS Member Orientation Class (MOC). See the SUS Bylaws (attached) for additional information. In the Member Orientation Class (which lasts approximately 1-1/2 hours) we will review SUS policies, procedures and guidelines and give you an opportunity to ask questions about the Club. The Dockside Orientation Class is approximately 4 hours and given on a docked boat (usually one of the SUS Skipper’s boats). We encourage everyone to enhance SUS sailing activities with sailing and boating classes. We believe it is important for all members to become active, contributing, participants in SUS. In return you can enjoy great sailing, programs and social events with some of the best people you may ever meet. This booklet contains all the information you will need to become an active participant in SUS. BRING THIS BOOK WITH YOU TO THE MOC. http://www.singlesundersail.org VISIT THE SUS WEBSITE singlesundersail.org for additional information and updates. The site requires a user name and password to access members only material. -

Cub Scout Parent Guide Welcome to the Adventure of Cub Scouts Den and Pack Information

Cub Scout Parent Guide Welcome to the Adventure of Cub Scouts Den and Pack Information: My Scout is in Pack: Pack meeting location: Pack meeting dates: Pack meeting time: Den meeting location: Den meeting dates: Den meeting time: Den and Pack Leaders: Den Leader: Phone number: Email: Cubmaster: Phone number: Email: What Is Cub Scouting? Scouting Is Family Oriented • Activities are intended for the whole family and families are always welcome at all Scouting activities! • Parents can work with their Scout on advancement requirements. The Cub Scout Den • Your child is a member of a Cub Scout Den. Dens include boys or girls from the same grade. • Dens typically meet 2-3 times per month, twice for regular den meetings and once for the Pack meeting. • Dens are led by a registered and trained Den Leader (usually a parent). • Den Leaders are helped by an Assistant Den Leader (usually a parent). • Den meetings involve learning, games, crafts, songs, and lots of FUN! The Cub Scout Pack • Your child is a member of a Cub Scout Pack (all Dens combined). • Packs meet once a month—all Cub Scout families are invited to attend. • The Pack meeting is led by the Pack’s Cubmaster (usually a parent). • The Pack meeting is the highlight of the month’s Den meetings and activities. • Pack meetings are designed to be fun and usually involve games, songs, skits, ceremonies, and presentations of awards. The Pack Committee • The Pack is run by a committee of volunteer parents. • The Pack committee is made up of positions like Secretary/Treasurer, Advancement Coordinator, Outdoor Activities Chair, Membership Chair, etc. -

Jackline Update

A P R I L 2 0 2 1 JACKLINE INSURANCE PROGRAM 2021 NEWS & UPDATES FEAR NO HORIZON - INSURANCE FOR GLOBAL CRUISERS & LIVING ABOARD The Jackline Insurance Program by Gowrie Group is a comprehensive insurance program designed to protect yachts and their owners cruising throughout the world. Our marine insurance experts understand the cruising lifestyle, and work with our clients to create customized insurance solutions to align with cruising plans and coverage needs. The Jackline Program includes key protection important to cruisers, such as world-wide navigation, approval for living aboard with a crew of two, personal property coverage, mechanical breakdown, ice damage, pollution liability, reef damage liability, loss of use, and more. The program is endorsed by Seven Seas Cruising Association (SSCA), underwritten by Markel Insurance, and managed by Gowrie Group, a Division of Risk Strategies. CONTENTS INSURANCE MARKET - UPDATE FOR CRUISERS The insurance marketplace has experienced unprecedented forces and undergone significant changes in the past few years. 2020 presented not only a global pandemic, but also delivered a Fear No Horizon continuation of the multi-year trend of extremely active, destructive, and costly Atlantic Hurricane Seasons. Many insurance companies have reacted to the multi-year catastrophic losses, by reevaluating their rates and in some cases, exiting the marine insurance market. These changes Insurance Market Update have left thousands of boat owners with a policy scheduled for non-renewal, and limited options for how to secure new coverage. Did You Know? The Jackline Insurance Program, underwritten by Markel and managed by Gowrie Group, is proud to confirm that we are committed to our cruising clients, and we have no plans to exit from the marine insurance market. -

Collecting Scouting Handbooks 1910 1911

Collecting Scouting Handbooks The ISCA Getting Started Collecting Series If you are now or were ever a Scout, your first Scouting “collectible” was probably your Cub Scout or Boy Scout handbook. Since Scouting was founded in 1908 and then incorporated in the United States in 1910, there have been millions and millions of Scouting handbooks distributed. In this introductory article we will only talk about Handbooks for the Boy Scouts of America. However, if collecting printed materials from Scouting catches your interest, there are many different possibilities that a collector can consider, from both the United States and around the world. Since 1911, there have been eleven completely different editions of the Boy Scout Handbook. The following is a brief summary of each one. 1910 68,900 copies The 1910 Handbook, also referred to as the “Original Edition”, was not new material but rather a compilation of existing information from two other sources. Soon after the incorporation of the Boy Scouts of America in February 1910, there was a huge demand for a handbook that could be used to support the efforts of the early United States Scouts. Ernest Thompson Seton, the first Chief Scout of the BSA, offered to prepare a book that could be used until the first “real” handbook could be developed. He took material from Baden-Powell’s Scouting for Boys that had been published in England in 1908 and his own Birch Bark Roll used by the Woodcraft Indians, an earlier outdoor program youth group, and combined them to make the first Boy Scouts of America Official Handbook. -

Life to Eagle Seminar

Life to Eagle Seminar Adopted by The Advancement Committee Orange County Council Boy Scouts of America January 09, 2012 01/09/12 7:30 PM Orange County Council Advancement 1 Committee Notice……… This presentation is NOT an official publication of the Boy Scouts of America nor the Orange County Council; however the contents have been reviewed and approved by three members of the the National Council Advancement Committee. It is prepared to assist Scouts, Parents, and Scout Leaders. Orange County Council 01/09/12 7:30 PM 2 Advancement Committee Introduction Earning the rank of Eagle Scout is a special event. Only around 5% of Scouts earn this distinction each year. In the history of the United States of America, over 2 million Scouts have earned the Eagle Rank since 1912. 01/09/12 7:30 PM Orange County Council 3 Advancement Committee To Achieve the Eagle Scout Rank a Scout Must Earn five prior Scouting Ranks Meet 60 achievement requirements Satisfactorily complete 1,255 different tasks Be reviewed by Adult Scouters at the Unit, District, Council and National level at least 70 times 01/09/12 7:30 PM Orange County Council 4 Advancement Committee Purpose of this Seminar Review the 12 steps from Life to Eagle Review the requirements for the Eagle Scout Explain the procedures used in Orange County Council Review the Eagle Scout Leadership Service Project Requirements 01/09/12 7:30 PM Orange County Council 5 Advancement Committee Target Audiences Star and Life Rank Boy Scouts Parents Scout Leaders Unit Leaders Unit Advancement Chairs Unit Committee Members 01/09/12 7:30 PM Orange County Council 6 Advancement Committee Who Sets Eagle Scout Requirements? Set by BSA National Committee Orange County Council Advancement Committee implements policies and procedures of BSA National and Council 01/09/12 7:30 PM Orange County Council 7 Advancement Committee The 7 Eagle Scout Requirements 1. -

International MARINE ACCIDENT REPORTING SCHEME

International MARINE ACCIDENT REPORTING SCHEME MARS REPORT No 160 February 2006 MARS 200604 Fall from Gangway 0220 Vessel all fast. Main shore gangway, which could 0900 Stations called fore and aft. Moorings tended and only be moved up-down vertically and not in a made tight as required. Duty officer on poop deck horizontal direction, nor could it be slewed in any for aft stations and Chief Officer on forward other direction, lowered to correct height. stations. No one was paying any particular Connecting gangway (sometimes referred to as attention near the gangway as it was located on an MOT gangway or formerly known as a brow) main deck and out of view from aft stations and was placed on the main gangway. The other end nobody was expected to visit the ship. of the brow was placed on the ship’s rails and 0918 Main engines tried out ahead/astern. made fast there. The ship’s safety net was used 0920 One person from the Seaman’s Club tried to board and a step ladder was made fast to ship’s railings the vessel, in spite of having been warned by the to facilitate the safe access onto the deck. Also a terminal operator (in his native language) against life buoy with a line was placed near the gangway. doing so, and caused the brow to over balance The gangway was manned at all times by a duty and he fell into the water along with the brow. A.B. The Cadet saw this happen from the forecastle deck and raised the alarm. -

Knots Knots Have Been Created So That They If You Can Tie These Knots Correctly May Perform a Certain Job Effectively

9th Huddersfield (Crosland Hill) Scout Group www.9thHuddersfieldScouts.org.uk Knots Knots have been created so that they If you can tie these knots correctly may perform a certain job effectively. then certainly you will be on your way to A good knot is easy to tie and just as becoming a competent rope worker. easy to untie, does not slip under strain To become proficient at tying knots, and can be relied upon. constant practice is necessary. This is There are only seven basic knots in use. best done by using a piece of rope These knots have been tried and rather than string. trusted by those who use knots While tying the knot, the feel of the constantly in their working and social knot and how your hands move in its life, people such as sailors, truckers, construction is as much a part of the soldiers, and dock workers. process of learning to tie, as is the These knots are: watching of the knot tying. the reef knot, Your ultimate aim should be to be able the bowline, to tie the knot in the dark, behind your the sheet bend, back, half way up a tree, or on a fisherman's knot, mountain top in a snowstorm. clove hitch, round turn and two half hitches, the timber hitch. Some points on ropes: Store all rope in a dry place; It is a good idea to label each Dry all ropes before putting them rope, with its length, size, use away; and age; As far as possible do not drag Rope is measured by its ropes along the ground or through circumference, not its thickness; rivers where the fibres of the When you tie knots pull them rope can be damaged; tight, a knot only becomes Inspect ropes carefully before effective when it is tightened. -

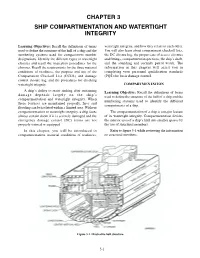

Chapter 3 Ship Compartmentation and Watertight Integrity

CHAPTER 3 SHIP COMPARTMENTATION AND WATERTIGHT INTEGRITY Learning Objectives: Recall the definitions of terms watertight integrity, and how they relate to each other. used to define the structure of the hull of a ship and the You will also learn about compartment checkoff lists, numbering systems used for compartment number the DC closure log, the proper care of access closures designations. Identify the different types of watertight and fittings, compartment inspections, the ship’s draft, closures and recall the inspection procedures for the and the sounding and security patrol watch. The closures. Recall the requirements for the three material information in this chapter will assist you in conditions of readiness, the purpose and use of the completing your personnel qualification standards Compartment Checkoff List (CCOL) and damage (PQS) for basic damage control. control closure log, and the procedures for checking watertight integrity. COMPARTMENTATION A ship’s ability to resist sinking after sustaining Learning Objective: Recall the definitions of terms damage depends largely on the ship’s used to define the structure of the hull of a ship and the compartmentation and watertight integrity. When numbering systems used to identify the different these features are maintained properly, fires and compartments of a ship. flooding can be isolated within a limited area. Without compartmentation or watertight integrity, a ship faces The compartmentation of a ship is a major feature almost certain doom if it is severely damaged and the of its watertight integrity. Compartmentation divides emergency damage control (DC) teams are not the interior area of a ship’s hull into smaller spaces by properly trained or equipped. -

Glossary of Scouting Terms Activities and Civic Service Committee

GLOSSARY OF SCOUTING TERMS activities and civic service committee. The council or Boy Scout. A registered youth member of a Boy Scout district committee responsible for planning, promoting troop or one registered as a Lone Scout. Must have and operating activities. completed the fifth grade and be 11 years old, or have earned the Arrow of Light Award but not yet be 18 advanced training. In-depth training for experienced years old. adult leaders, such as Wood Badge. Boy Scouts of America (BSA). A nationwide organiza- advancement. The process by which a Boy Scout meets tion founded February 8, 1910, and chartered by the certain requirements and earns recognition. U.S. Congress June 15, 1916. Alpha Phi Omega (APO). A coeducational service Boys’ Life magazine. The magazine for all boys, fraternity organized in many colleges and universities. published by the Boy Scouts of America. It was founded on the principles of the Scout Oath and Law. Bronze Palm. An Eagle Scout may receive this recogni- tion by earning five additional merit badges and com- Aquatics Instructor, BSA. A five-year certification pleting certain other requirements. awarded to an adult who satisfactorily completes the aquatics section at a BSA National Camping School. Brotherhood membership. The second and final induc- tion phase of membership in the Order of the Arrow. area director. A professional Scouter on a regional staff who relates to and works with an area president in BSA Lifeguard. A three-year certification awarded giving direct service to local councils. to Boy Scouts who meet prescribed requirements in aquatics skills. -

Download LYDE 05 FIFE RAILS YO PUMP

Euromodel – Lyde(1787).05. fife rails to pump. January 2021 TRANSLATION LINKS 1. type into your browser ... english+italian+glossary+nautical terms 2. utilise the translation dictionary ‘Nautical Terms & Expressions’ from Euromodel website An interpretive build of the Lyde English Schooner 1787 Scale 1:80 Checked the Resource File ? 05.FIFE RAIL to PUMP January 2021 My interpretive build is based on the supplied drawings, the kit material – and an amount of extra mater ial. This work only illustrates how this ship might be built.The level of complexity chosen is up to the individual This resource information was based on the original text supplied by Euromodel and then expanded in detail as the actual ship was constructed by the author, Peter Coward. Neither the author or Euromodel have any commercial interest in this information and it is published on the Euromodel web site in good faith for other persons who may wish to build this ship. Euromodel does not accept any responsibility for the contents that follow. 1 Euromodel – Lyde(1787).05. fife rails to pump. January 2021 [To navigate through the contents – use ‘control + click’] Contents CHAPTER 1: DECK ACCESSORIES ...................................................................................... 4 Hatchways .............................................................................................................................. 6 Quarter Deck: 1 & 2 ........................................................................................................... 6 Coaming Construction